The historical notebooks of Dorothy Chadwick

Guest post by Elizabeth Grimshaw, former member of the department of Archives and Modern Manuscripts, now a PhD candidate in English Literature at the University of Buckingham.

Dorothy Chadwick described history as “a pursuit as exciting and, too often, as baffling as any belonging to the realms of Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot.” (MS Add 8387/6/89vi). Combining this excitement with exacting research methods, Dorothy’s personal and family papers, contained in MS Add.8387, reveal her methodical historical research practices and her wide social network of fellow scholars.

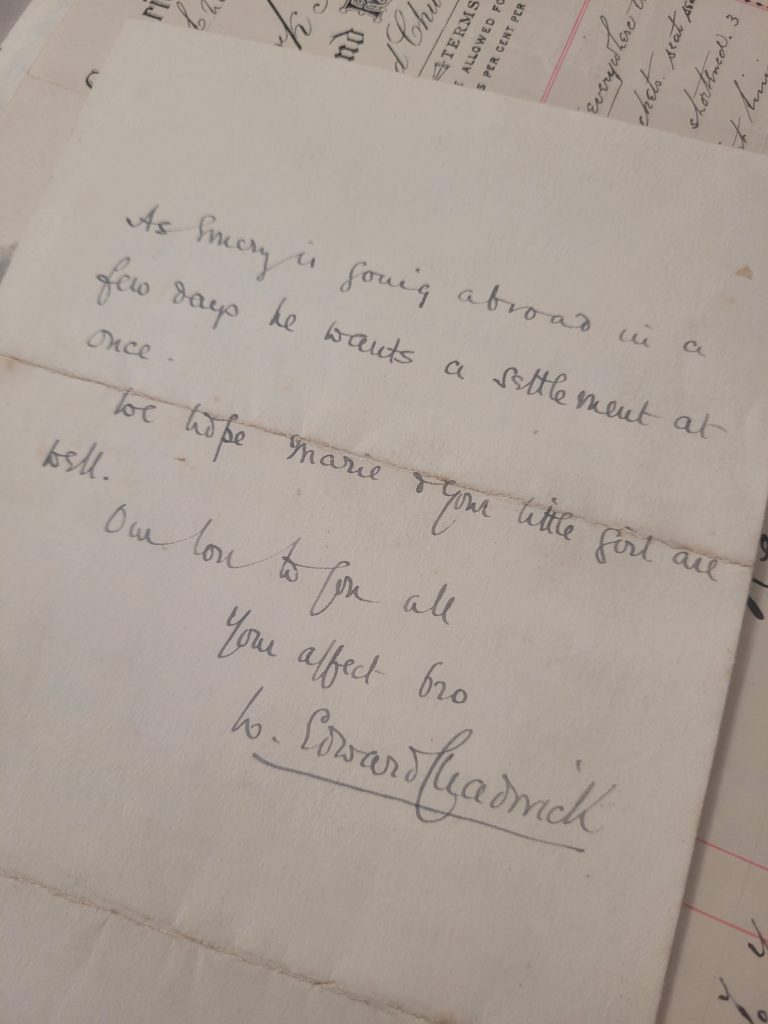

Dorothy Verena Murray Chadwick was born on 8 March 1900 to Marie Verena Chadwick (née Lofthouse) and James Murray Chadwick. Her uncle William Edward Chadwick welcomes her warmly in this letter to her father.

“We hope Marie & your little girl are well

MS Add.8387/4/1

Our love to you all

Your affect bro

W. Edward Chadwick”

William Edward Chadwick was an author, penning Thornleigh House: A North-Country Story (1891), My Sister’s Welfare: A Story (1899) and Ethel Hardman: A Story of Self-Discipline (1901).

Another of her uncles, Hector Munro Chadwick, was the Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon and the founder and head of the Department for Anglo-Saxon and Kindred Studies at the University of Cambridge. He and his wife, Nora Kershaw, a fellow Cambridge scholar, worked closely and published The Growth of Literature, 1932–1940, and Early Scotland, 1949, together. Those interested in Hector Munro Chadwick’s rich interdisciplinary legacy can still attend the annual memorial lecture in his name by a scholar invited to Cambridge for the occasion.

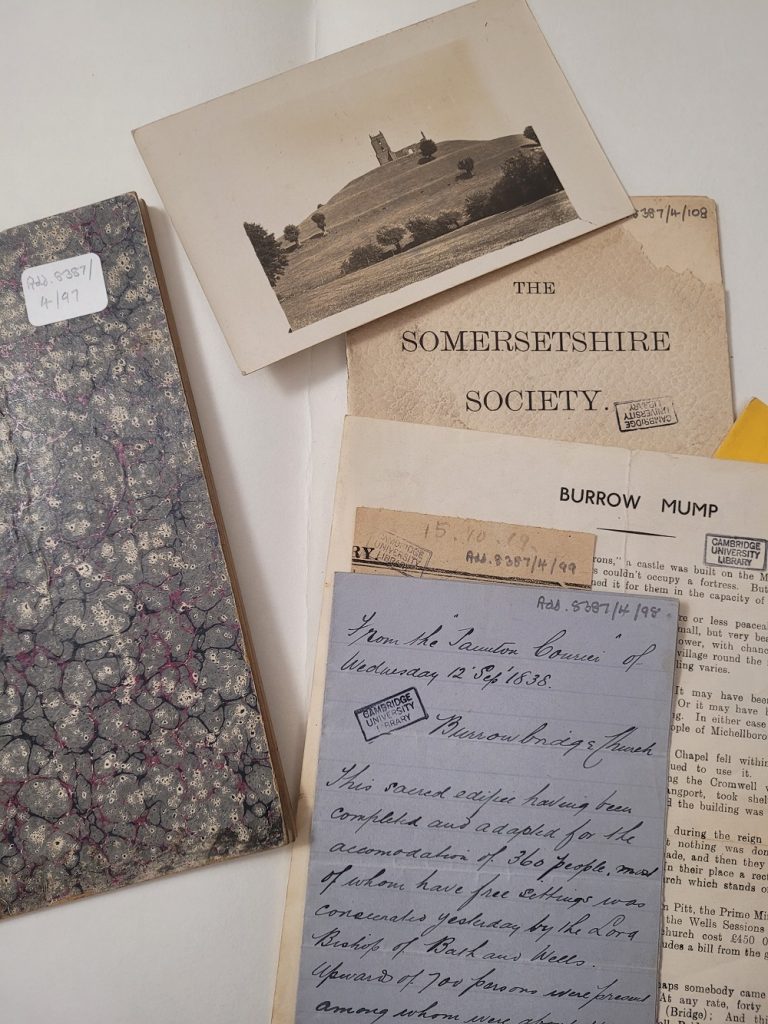

Dorothy’s father also took an interest in history, with a particular focus on the parishes of which he was curate. The Reverend published principally on the Burrow Mump, the location of a Saxon look-out point, a Norman castle, and a medieval chapel, the ruins of which remain visible today.

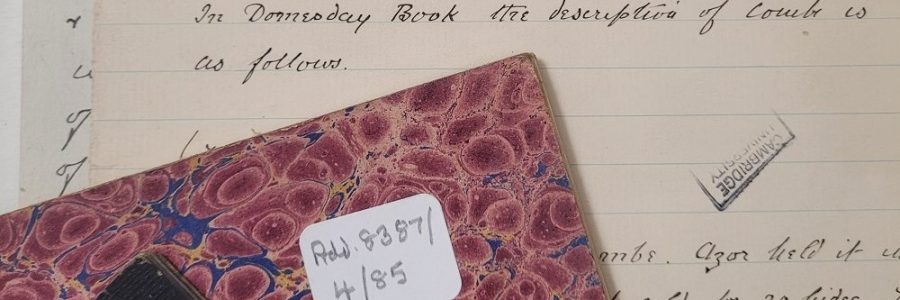

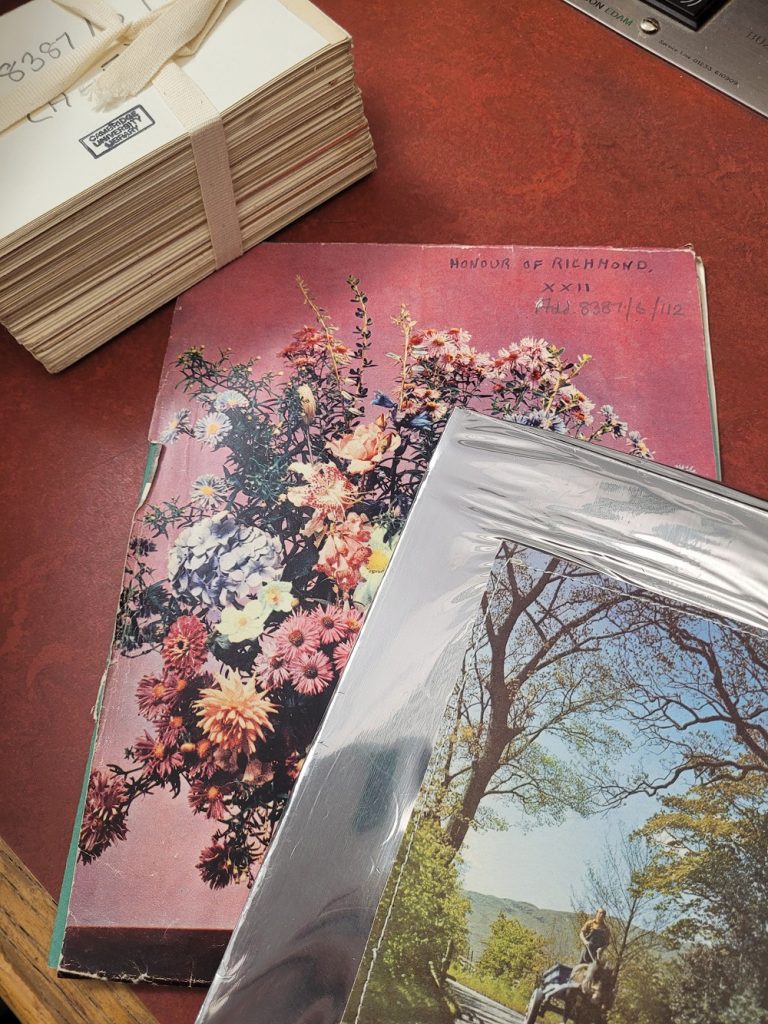

Dorothy clearly shared the family passions for literature, language and history. She has left behind a collection of research papers which are meticulously organized. Each of her 177 exercise books are filled with manuscript transcriptions and her own translations from the Domesday book and other early archival documents. Not only are her notebooks stored in alphabetical order, she also created an index for each individual book, citing the original source material for her translations. She created a card catalogue system in order to index her overall body of work for cross referencing across volumes. An impeccable researcher, she also shows her creative side by covering her workbooks in beautiful collages, with images ranging from floral photographs to pastoral drawings.

One of Dorothy’s typescript articles, responding to Dorothy Whitelock (1901-82), of Newnham College, opens with a lyrical description of the passing of time, evoking the imaginary march forward of historical events:

“the Norman conquest of 1066, while marking the end of one epoch in English history and the commencement of another, did not cause such an immediate and general upheaval in the English manner of life as we are tempted to imagine when the past is presented to us in the form of a pageant. Many of us, in our schooldays, absorbed mental visions of the landing of Duke William and his well-armed followers on the Sussex coast, of the heroic but vain resistance offered by the ill-equipped English host, and of night falling over Saxon England on a battlefield where most of her great men lay dead. “

MS Add 8387/6/89i

Dorothy took a particular interest in using archival resources to recover the history and land holdings of a woman referred to as Eddiva ‘the Fair’. Dorothy was able to cross reference a wide number of primary sources to create a compendium suggesting Eddiva to be one of the largest estate holders of her time period, recovering a woman’s history usually concealed by the names of her male relatives.

Dorothy’s notebooks contain notes on research into parishes from A almost to Z, of Great and Little Abington straight through to Wood Ditton, and she consistently and generously researched on behalf of her correspondents, who often seem to be Reverends interested in the history of their parishes, much like her own father. Dorothy, as many male members of her family are, should be remembered as a Chadwick historian of the highest calibre.

Great research and recovery of D.C’s interests and discoveries.

Never knew about Her and her lovely notebooks; Thank you for this revelation!