Culinary inspiration and dietary counsel from the Curious Cures project

This post comes as part of our series from the Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries project, courtesy of Project Cataloguers Sarah Gilbert and Clarck Drieshen…

Have you ever wondered what food and drink medieval people enjoyed during Christmastime? In the Middle Ages, food was not only a source of sustenance and enjoyment, or a matter of correct religious practice: it was also considered essential for maintaining and restoring one’s health. Unsurprisingly then, recommendations for particular foods or dietary regimes appear in many of the 100 manuscripts in the Curious Cures project that we have digitised and catalogued so far.

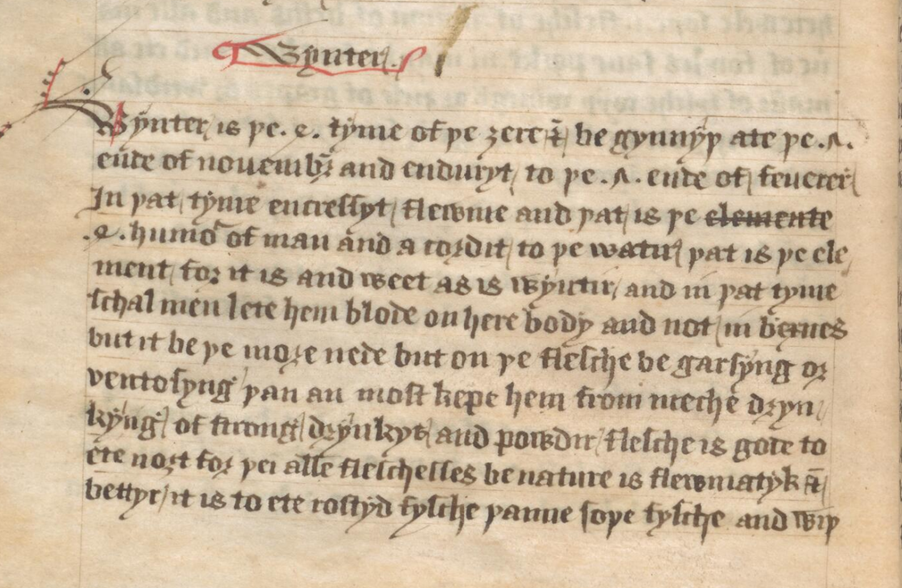

Cambridge, Magdalene College, MS Pepys 878, f. 172v

Medieval medical writings often gave dietary advice that focused on regulating the four bodily humours: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. These humours were believed to govern the human body and could change in their proportions according to diet, the season, or current sign of the Zodiac. In winter, it was thought that the amount of phlegm would increase: just as the season was cold and wet, so the body would have more of this cold and wet humour inside it. Consequently, one dietary text in a 15th-century English medical manuscript advises moderation in drinking (‘kepe hem from meche drynkyng of strong drynkys’) – just as we are advised today not to overindulge. It also recommends that meat be avoided, because its ‘nature is flewmatyk’, and so would aggravate the imbalance of phlegm in the body; if fish is on the menu, ‘better it is to ete rostyd fysche þanne soþe fysche’ (i.e. roasted rather than poached). Instead, spices that were considered to have hot and dry properties should be used: mustard and pepper eaten with your meat, for example, or by chewing on a spicy herb known as ‘pelettur of Spayne‘. These could counterbalance the cold and wet phlegm and had purgative properties, making ‘þe spittyn owte gleste and flewme’.

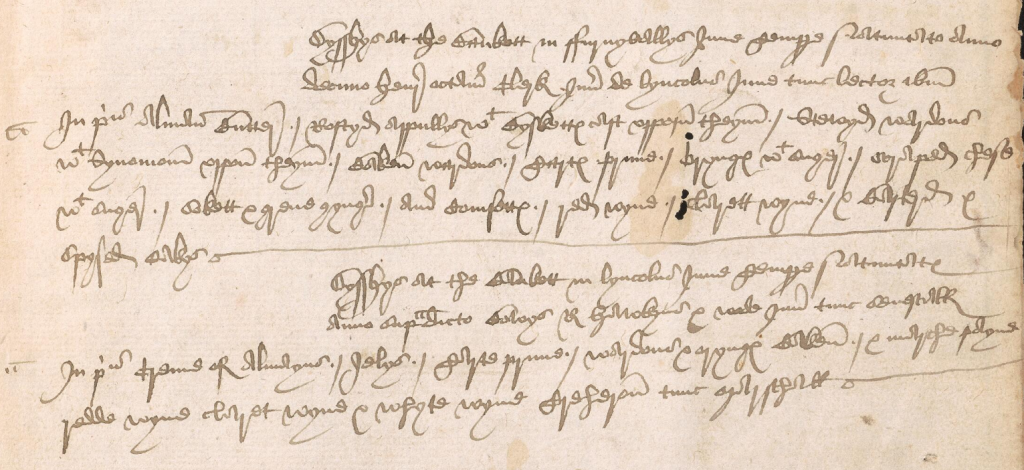

Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 2994, f. 209r

To what extent did medieval men and women follow such dietary advice? One reader who evidently did not was Edward Cushyn, a lawyer in London who attended two boozy Christmas banquets in 1518 and made a note of their menus in a legal reference book that he owned. The first of these was held at Furnival’s Inn: despite its name not a pub or a hotel, but one of the now-defunct Inns of Chancery, which offered training and housing to legal clerks (much as the Inns of Court did and still do for barristers). The feast included almond butter, roasted apples sprinkled with biscuits, ‘warden’ pears (a type of cooking pear) baked with cinnamon, prune tart, oranges with sugar, finely sliced cheese with sugar, sweet delicacies with ‘green’ ginger, confectionary, red wine, claret wine, spiced sweet wine, and spiced cakes. The other feast, at Lincoln’s Inn, had a similar menu: cream of almonds, jellies (which probably involved meat juices in their preparation), prune tart, baked ‘warden’ pears and oranges, marzipan, red wine, claret wine, and white wine. These menus attest not only to the richness and variety of foods available in late medieval London, but also an international trade that brought fruits, spices and wines to the tables of the wealthy.

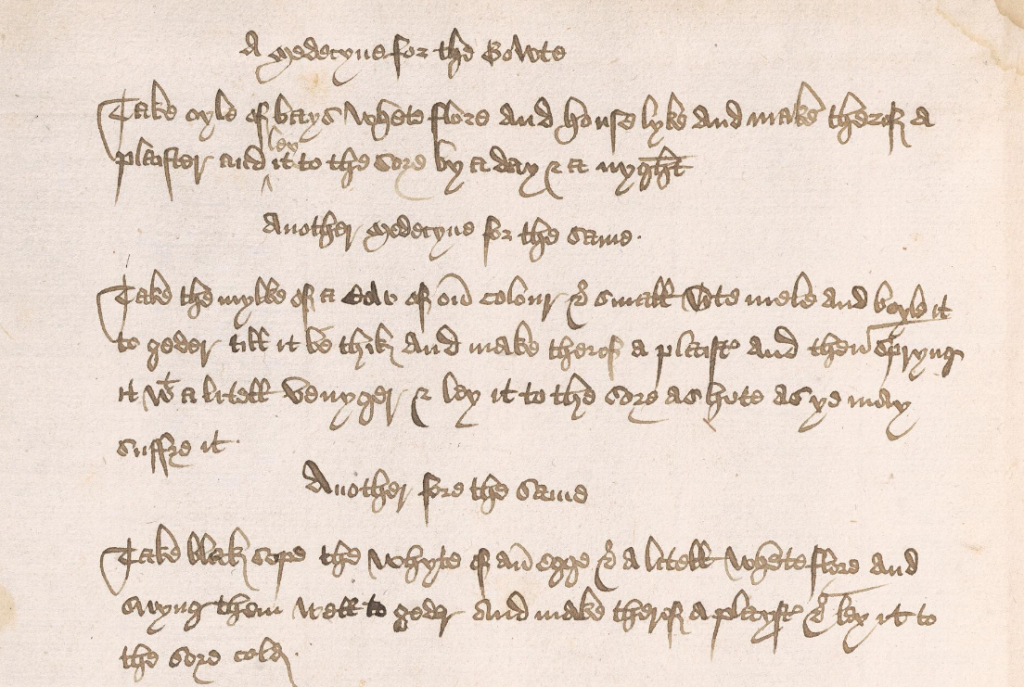

The consequences of such a rich diet may be seen elsewhere in this manuscript. It is common to find medical recipes added to many different sorts of book, not just medical ones: the Curious Cures project encompasses bibles and Books of Hours, books of theology and copies of the writings of Church Fathers, alchemical texts, works of literature, herbals and, as here, legal manuscripts. Typically, the medical recipes in these manuscripts are peripheral additions to the margins or endleaves, and their contents are miscellaneous or have no obvious organising principle. In Edward Cushyn’s legal book, however, we find sixteen separate remedies for a single complaint – gout (sometimes also described as ‘bone ache’) – grouped together on three pages (ff. 205v-206v). They are all variations on the same theme: ingredients are combined to make a ‘plaster’, a thick medicinal poultice or ointment, that was then to be smeared on the affected area. Gout is a painful condition that can be exacerbated by a diet high in meat, alcohol and sugar, and for which there was no known cure during this time. Little wonder that sufferers sought out so many different cures, whose components ranged from the simple and everyday to the outlandish and bizarre…

Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd.6.9, f. 19r

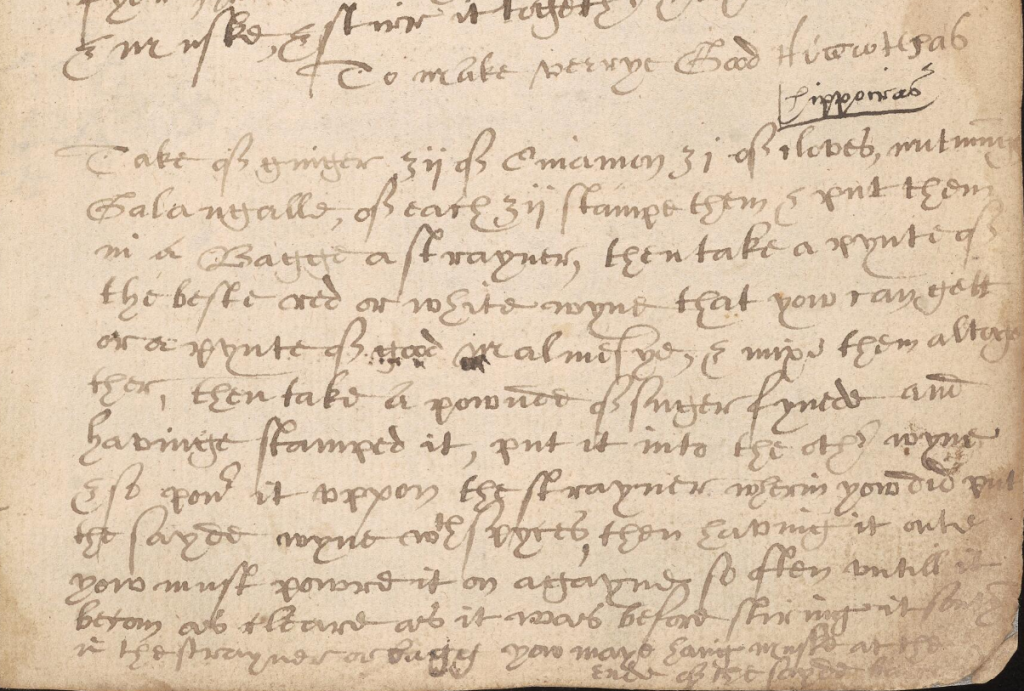

The spiced alcoholic drinks and foods that Edward Cushyn recorded were not necessarily considered unhealthy: it depended on the season and a person’s humours, and recipes for them commonly appear among collections of medical preparations. A late 16th-century collection of medical recipes features an instruction on how to make a drink called ‘Hippocras’: it sounds a lot like the mulled wine we drink nowadays, and was considered to have health-giving properties. Its name derives from the Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460–c. 370 BC), and specifically from a filter bag known as ‘Hippocrates’ sleeve’. Recipes for ‘Hippocras’ vary, but they almost always contain sugar as a sweetener and the spices cinnamon, cloves and ginger. The drink was taken cold; it was thought ‘hot’ enough with the spices it contained. In this manuscript, the recipe also adds nutmeg and galangal. It advises that red wine, white wine or ‘malmsey’ (a type of wine made from Malvasia grapes) are all suitable bases. The mixture must be filtered repeatedly through the bag until it is completely clarified.

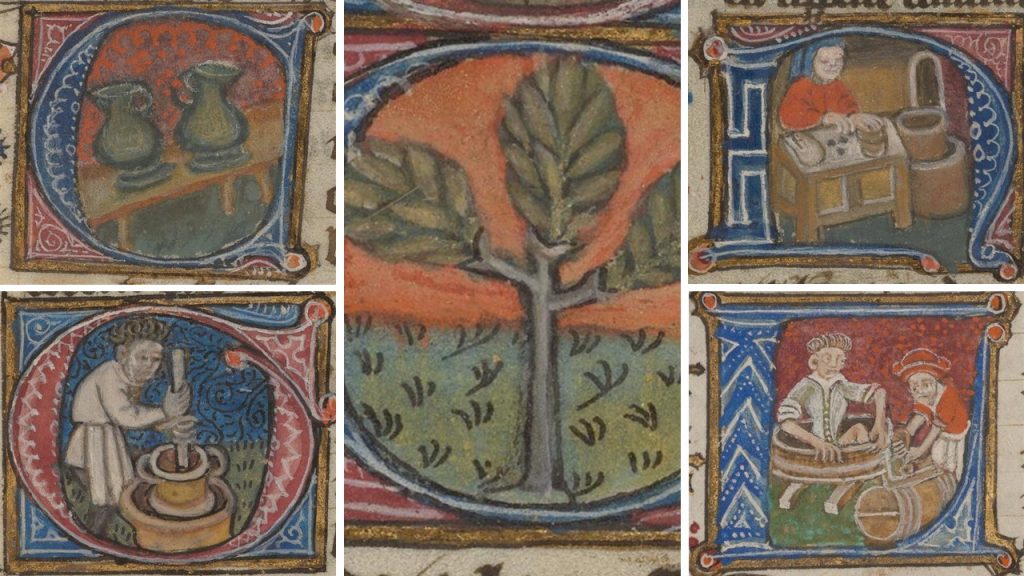

nutmeg (f. 81v), wine-making (f. 50v) and grinding galangal (f. 80r).

We cannot usually recommend the prescriptions we find in medieval medical manuscripts (especially those for gout), but we have added a transcription and translation here in case readers are looking for historical inspiration for their Christmas festivities:

Translation: To make very good Hippocras

Take 12 drachms of cinnamon, 11 of cloves, and 12 of nutmeg and galangal each, crush them and put them in a filter bag. Then take a pint of the best red or white wine that you can obtain or a pint of good Malvasia and mix them all together. Then take a pound of refined sugar and after crushing it, put it into the remaining wine and then put it through the filter in which you put the aforementioned wine with spices. Then, after it has come out, you should pour it on the strainer again as often until it becomes as clear as it was before stirring it in the filter or bag. You may hang nutmeg at the end of the said bag.

Edition: To make verrye good Ηiπωκρας [Hippocras]

Take of ginger ʒij of Cinamon ʒj of cloves, nutmunge, Galangalle, of each ʒij stampe them and put them in a Bagge a strayner, then take a pynte of the beste red or white wyne that yow can gett or a pynte of good Malmesye, and mixe them altogether, then take a pownde of suger fynede and havinge stamped it, put it into the other wyne and so poure it vppon the strayner wherein yow did put the sayde wyne with spyces, then having it oute yow must powre it on agayne so often vntill it becom as cleare as it was before stiring it so[m]tyme in the strayner or bagg yow maye hang muske at the ende of the sayde bagge.

A recipe for ‘Hippocras’ in Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd.6.9, f. 19r

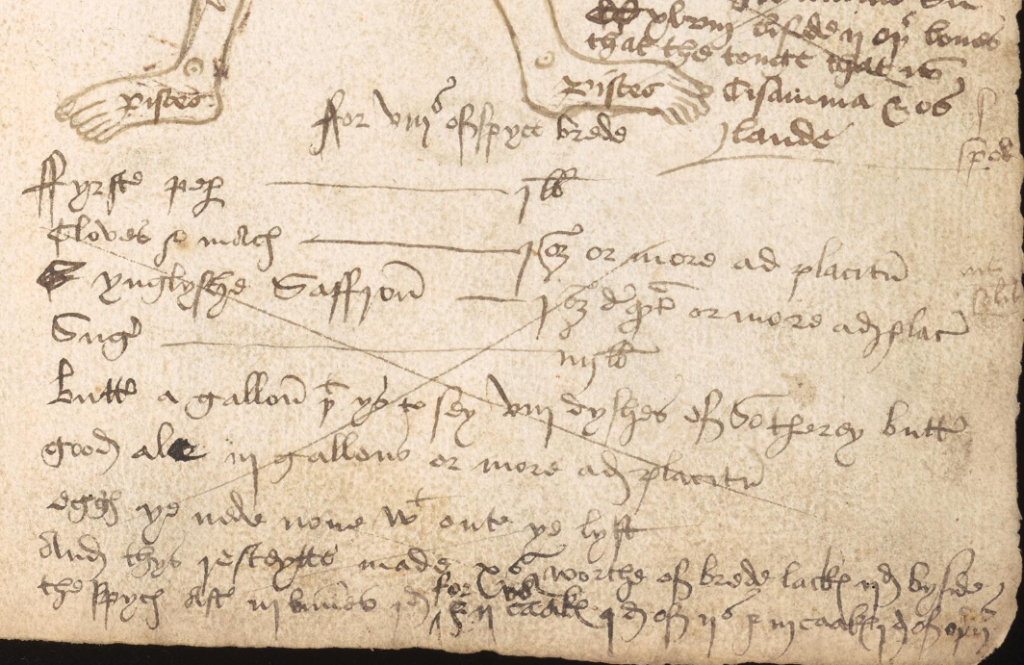

Other potentially festive foods for which recipes appear in the Curious Cures manuscripts include spiced breads, crystallised ginger and gingerbread. A list of ingredients for ‘spice brede’ appears in a late 15th- / early 16th-century compilation of medical, herbal, astrological, uroscopic and other texts. Some medical or culinary recipes describe how much of each ingredient should be used in general terms: ‘a great quantity’, ‘several’, ‘as much as the mixture allows’, ‘a handful or two’. Here, by contrast, the measurements are specific: a pound of pepper, an ounce of cloves and mace, an ounce and three-quarters of English saffron, four pounds of sugar, a gallon or ‘eight dishes’ of ‘Sotherey butter’, three gallons of good ale. Eggs are optional: ‘ye nede none without ye lyst’ (i.e. unless you want them).

Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.5.11 Clockwise from leftL roasting malt grains to make ale (f. 51r), milking a cow to make butter (f. 77v),

eggs from a hen (f. 76r), saffron crocuses (f. 80v), mace from a nutmeg aril (f. 81v).

Since it lacks instructions, and omits core ingredients such as flour, it is likely this was a way of adapting a bread recipe that the reader already knew. The baker also had scope to exercise his or her judgment, since several of the quantities are followed by the statement ‘or more ad placitum’ (i.e. as you please). All of the ingredients would have been readily to hand in London, where this manuscript was likely compiled. The saffron was likely brought down from Saffron Walden in Essex, where it was widely cultivated, and the author of the recipe clearly preferred a certain type of butter, apparently from rural Norfolk where the village of Southery is located.

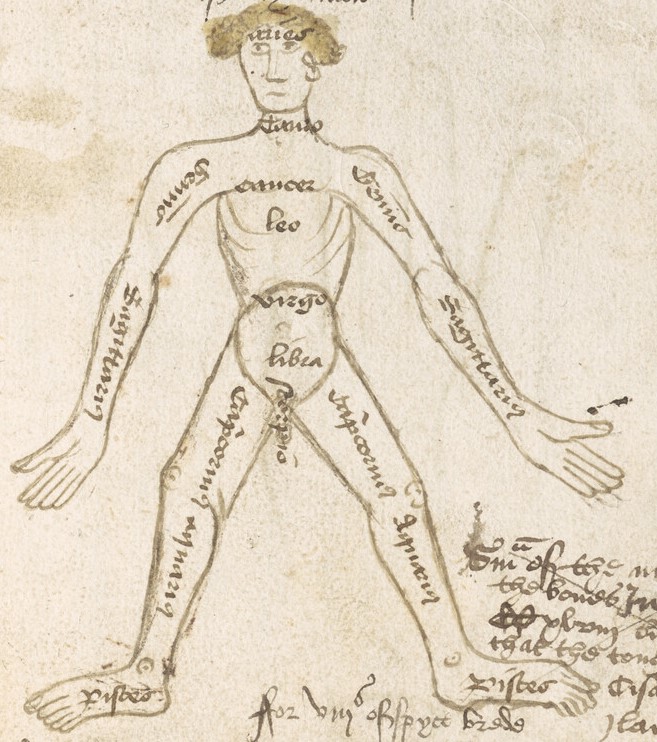

Festive recipes and feasting are nowadays often followed in short order by New Year’s resolutions for abstinence, a healthier diet and more exercise. For the medieval readers of Aldobrandino da Siena’s Régime du corps, moderation and physical activity were prescribed too, in chapters on drinking water or wine, and on walking or swimming. If these options did not appeal, others were certainly available. The recipe for spice bread in MS Ee.1.15 is situated directly under a simplified version of the ‘Zodiac man’ diagram. Common accompaniments to European medieval medical texts, these diagrams illustrate which part of the body was governed by which sign of the Zodiac. This was important information that determined the timing of surgical procedures and in particular bloodletting. This too was intended to regulate the body’s humours: by bleeding a patient, an excess of the sanguinary humour could be released, helping to restore the proper balance. We can be grateful that this is no longer a recommended remedy for that extra mince pie, roast potato or slice of spiced bread…

Whatever you choose to eat and drink over the next few weeks, whether it is sweetly spiced, or cold and wet, or hot and dry, we hope that your humors will remain entirely in balance into 2024 and we cordially wish you a Curious Cures Christmas!

Absolutely wonderful! Will try and transcribe the recipe for spiced bread and recreate it! Always keen to recreate original C16 recipes!