Thomas Wort, ‘leech’, and his book of remedies

This post comes as part of our series from the Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries project, courtesy of Project Conservator Marina Pelissari and Project Cataloguer Clarck Drieshen.

Little is known about the men and women in medieval England who had no formal education in medicine but were sought out by many for their healing knowledge. These informal medical practitioners, known as ‘leeches’, played an important role in a society where university-trained and licensed physicians were expensive and hard to come by, but their names have often gone unrecorded. A fifteenth-century manuscript containing a collection of over two-hundred Middle English medical recipes at Cambridge University Library (MS Add. 9309) not only offers a window onto the medical practices of one such leech, but also preserves his name. Until recently this precious information was not easily accessible to scholars or librarians due to the manuscript’s fragile condition. As part of the ongoing Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries project, the manuscript has been the subject of meticulous conservation work by Marina Pelissari of the University Library’s Conservation and Collection Care Department. By making it accessible again, her work has helped in in the discovery of tantalising details about the manuscript’s earliest history.

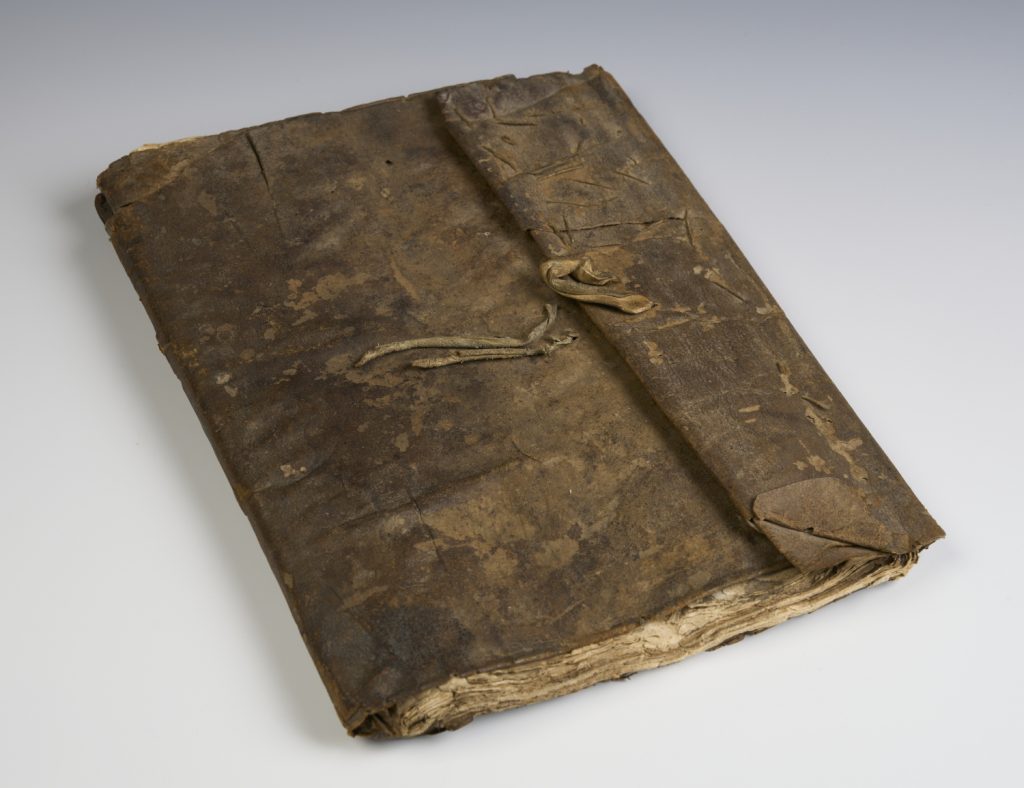

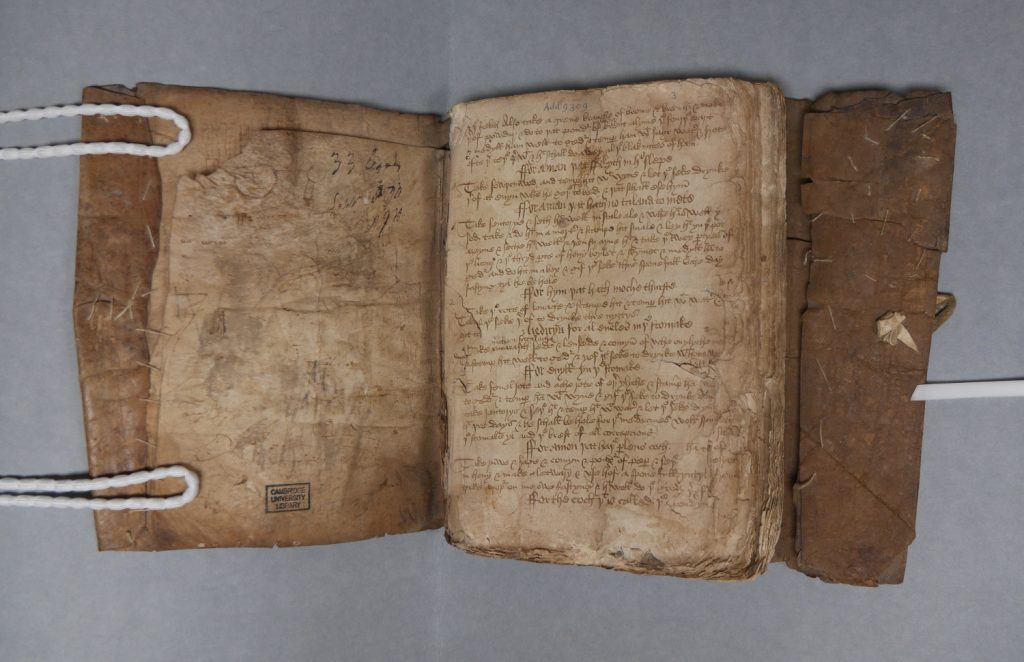

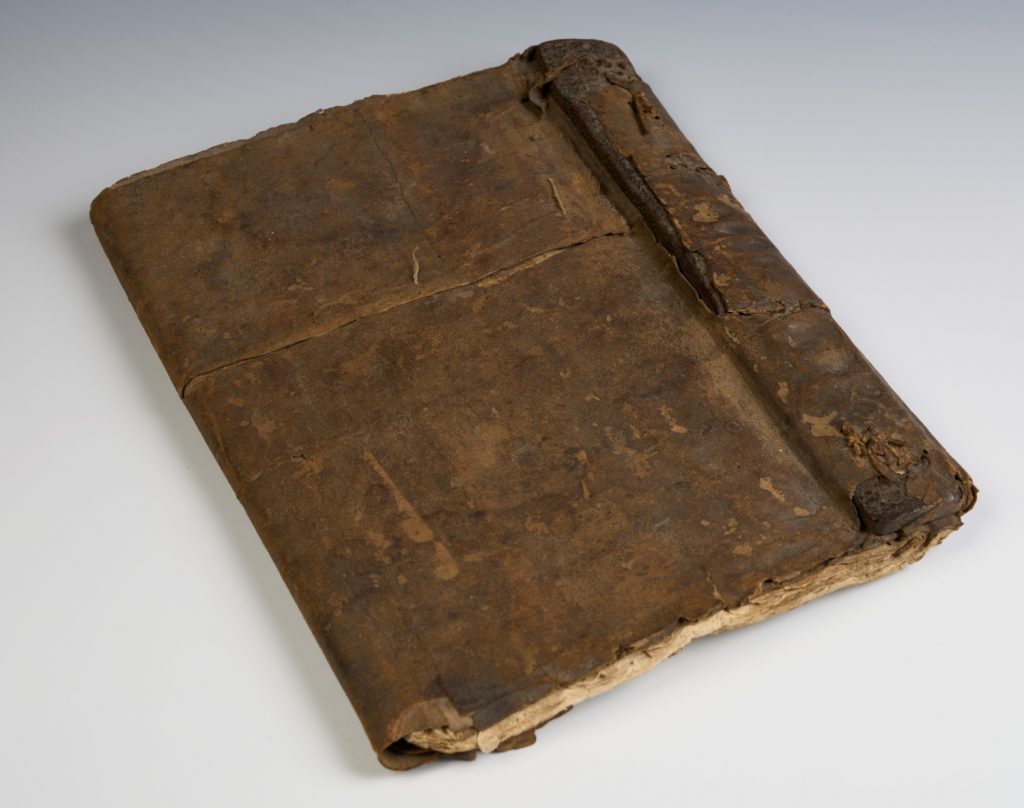

The manuscript comprises just over thirty paper leaves, bound in a light flexible parchment binding, and measures only 190 x 120mm. An extended parchment flap on the lower cover wraps around the fore-edge of the paper leaves and was originally secured to the front cover with leather straps, giving the book’s contents some protection against the elements. It was evidently designed to be portable – and it is easy to imagine a medical practitioner carrying it with them, perhaps as they travelled to visit their patients.

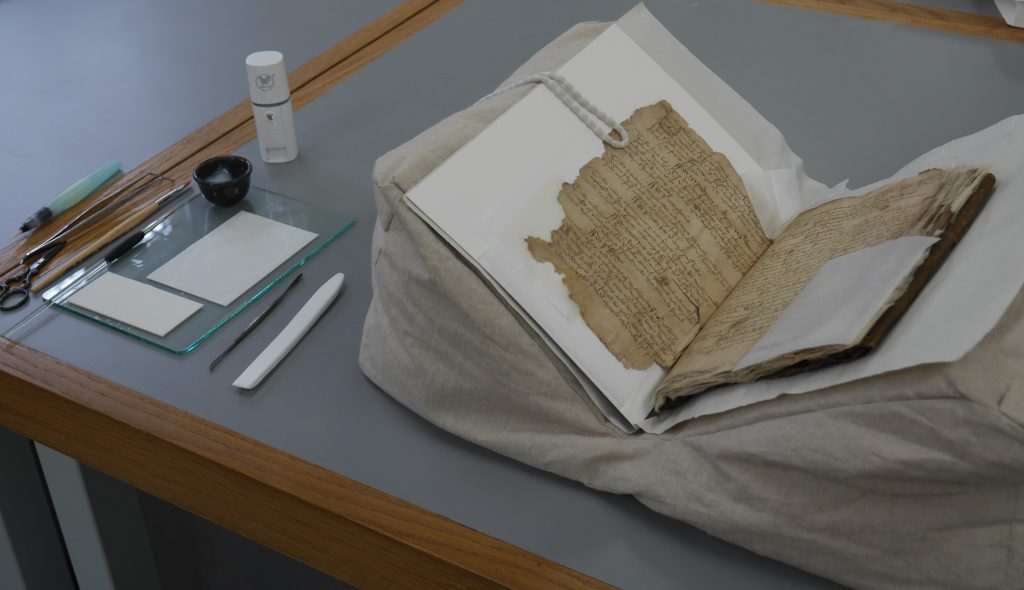

We can certainly see that the book has been heavily used over a long period. When the University Library acquired the manuscript at an auction in 1995, it was in an extremely fragile state: its paper leaves had been seriously affected by water and mould, making their edges soft and easy to tear. Additionally, there were folds, creases, and torn surfaces that obscured the contents and made handling the book quite difficult. Given its condition, the manuscript could be consulted in the Manuscripts Reading Room only with a conservator providing guidance and assistance in its handling.

At the start of the Curious Cures project, it was evident that the manuscript needed conservation work before it could be catalogued and photographed in full. Determining what types of treatments were needed, and how these should be executed, required careful discussion by conservators and curators. Some of the manuscript’s features – including signs of wear and tear – provide important evidence of its historic use. This raised questions about the extent to which it should be cleaned and to which the repairs should visibly alter its appearance. Following careful deliberation, and in line with standards of conservation best practice, a strategy of minimal intervention was chosen: this balanced the need to stabilise the manuscript’s leaves and make its written contents accessible with the need to retain its historically significant material aspects.

The chosen conservation strategy is most clearly visible in the way that Conservator Marina Pelissari has repaired the fragile edges of torn paper leaves: the repair tissues used to stabilise these edges have not been trimmed to replicate the original dimensions of the leaves, but so that they bridge the gaps across the meandering shapes in the leaves in their present worn and well-used condition.

Less noticeable is how the conservation principle has informed the treatment of threads that were used to sew together the pieces of parchment that formed the manuscript’s medieval wrapper. Perhaps at an early stage, various of these stitches broke and the threads’ loose ends started to unravel. To stabilise the composite binding without significantly altering it, the thread ends were reattached to the cover using an acrylic adhesive that does not soak or penetrate deep into the absorbent fibres, and by applying the adhesive only sparingly.

In some cases, the decision was made not to intervene at all. The manuscript’s spine comprises a thick strip of dark leather that would have originally sat perpendicular to the pages. Subsequently, the spine collapsed, causing it to sit flat at an even level with the lower cover. The dislocated spine does not cause handling difficulties or damage the paper leaves; it may even have resulted from the manuscript being compressed in a pouch or bag while it was being carried around. Its position has therefore been left unchanged.

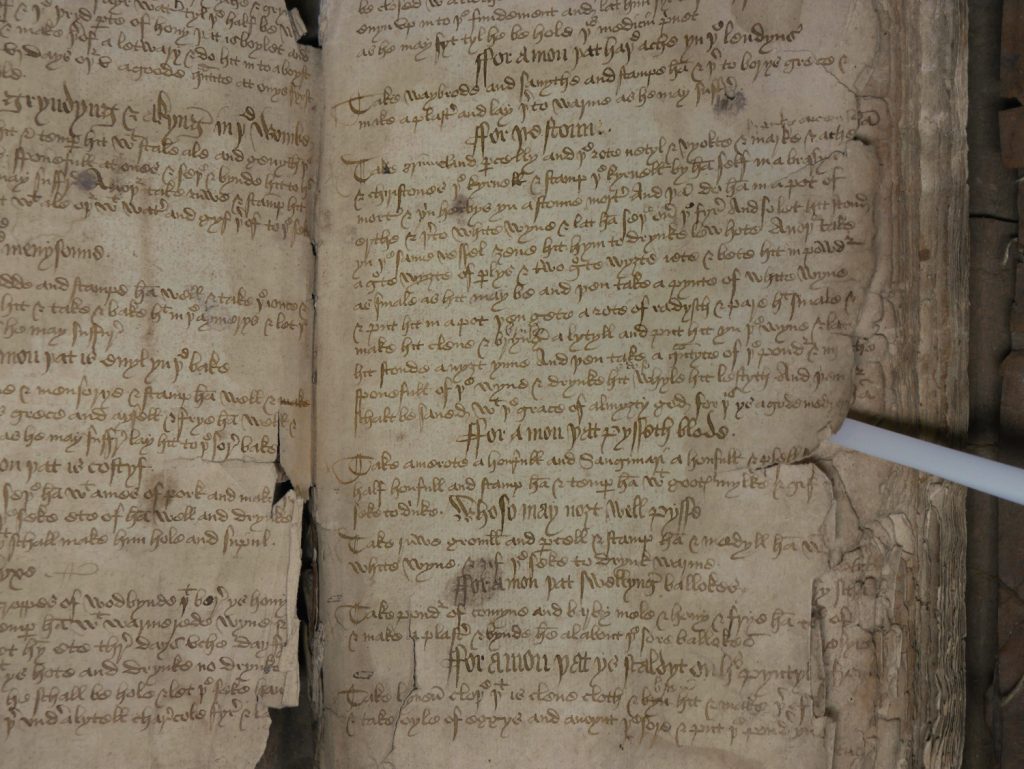

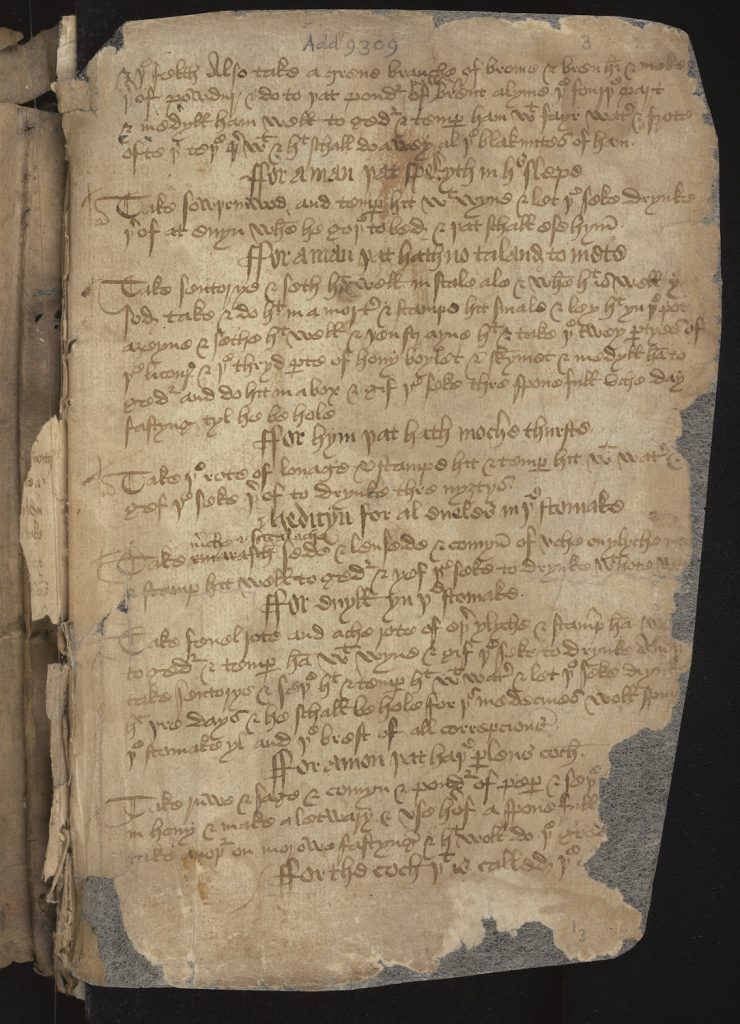

After the manuscript’s pages had been stabilised, unfolded, and cleaned, its contents could be accessed in a safe manner. This has enabled cataloguers to take stock of the great variety of recipes that are contained in the manuscript. Among the collection are recipes for treating wounds, swellings, ulcers, aches, cramp, migraine, epilepsy (‘falling evil’), excessive sweating, trembling hands, nosebleeds, fevers, and snake bites; for getting rid of lice and worms; and for helping patients with falling asleep and conceiving a child.

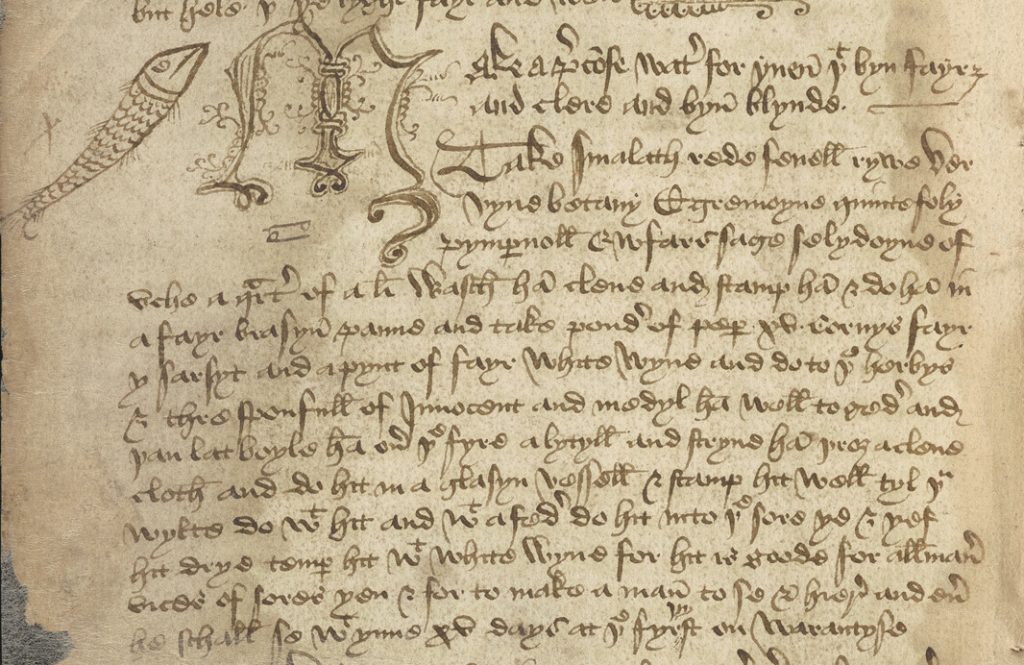

Most cures are based on herbs and other natural ingredients that would have been readily available. For example, for restoring sight to sore eyes, one is told to mix smallage, bronze fennel, rue, vervain, betony, agrimony, cinquefoil, pimpernel, celandine, and eyebright together with the powder of fifteen peppercorns into a pint of white wine, and then add three spoons of a young boy’s urine. After boiling the resulting mixture, it should be gently applied to the eyes using a feather.

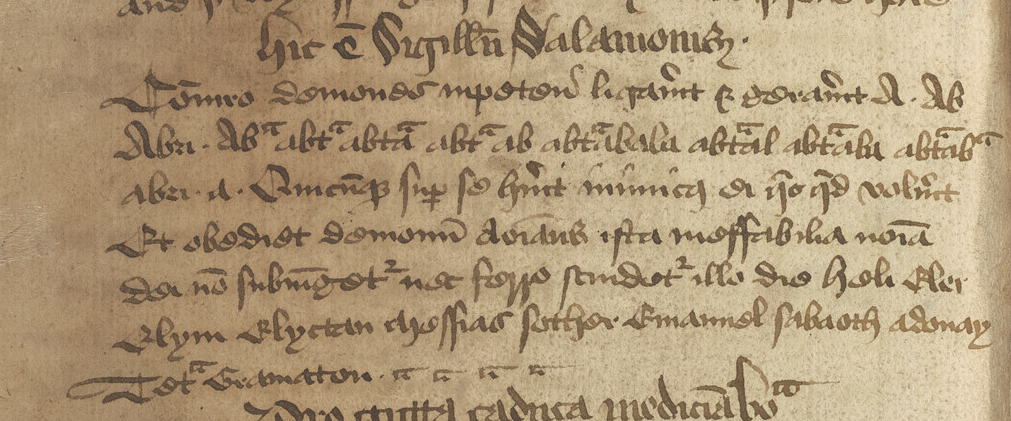

The manuscript also contains unusual texts relating to the supernatural, including instructions in Latin for making a magical amulet, called the ‘Seal of Solomon’, that protects its bearer against demons. Although its name refers to the signet ring with which the Old Testament King Solomon was able to control demons, this instruction tells the reader to make an amulet with an abracadabra-type of formula written on it instead.

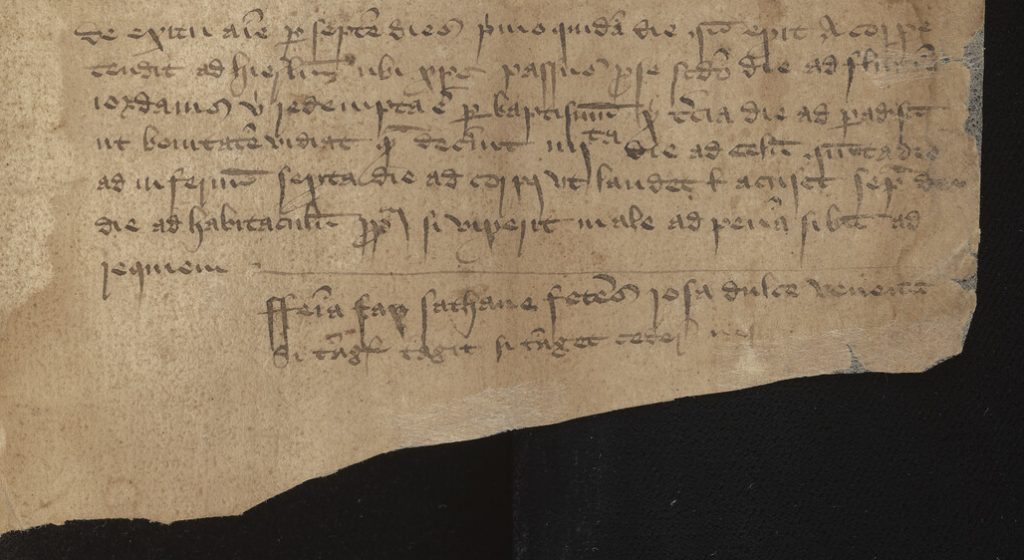

At the manuscript’s very end, an account was added that describes a soul’s seven-day pilgrimage to holy sites on earth and the spiritual worlds of Heaven and Hell immediately after death. It may ultimately derive from the Visio Sancti Pauli – a Latin version of the fourth-century apocryphal Apocalypse of Paul, which was originally written in Greek. With texts such as these, the manuscript reflects concerns about both the physical and spiritual wellbeing of patients.

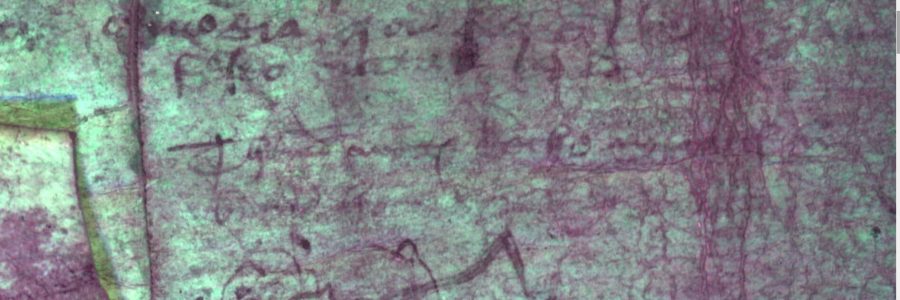

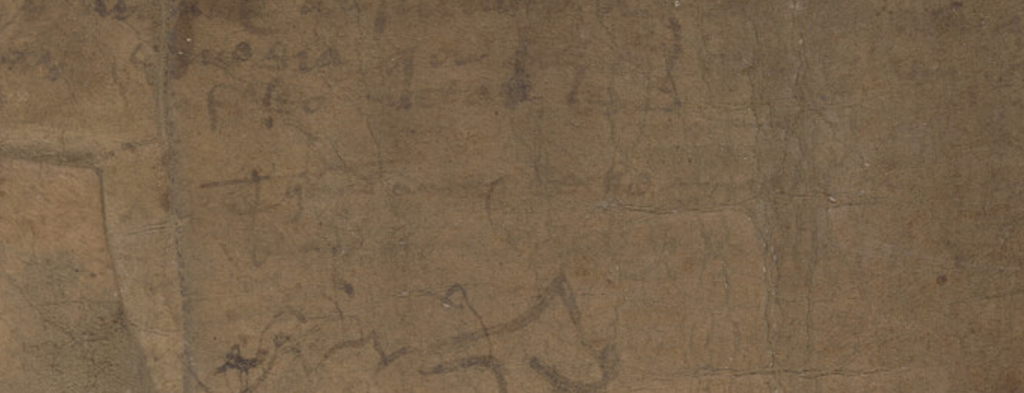

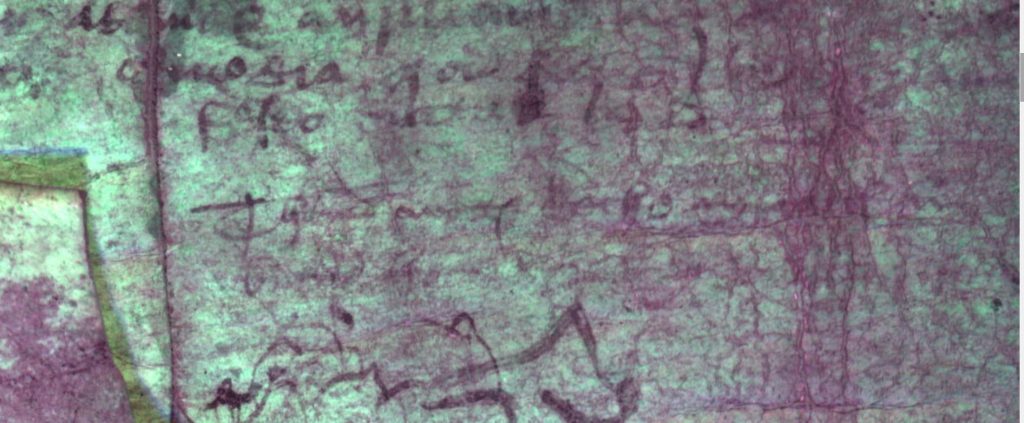

Perhaps the most exciting consequence of the manuscript’s renewed accessibility has been the opportunity to recover obscured inscriptions with the help of state-of-the-art photography. It is possible to discern with the naked eye an inscription on the inside of the rear cover, but its legibility has been seriously affected by layers of dirt. After having been hidden for more than half a millennium, this inscription has now been made more clearly visible, thanks to multi-spectral imaging undertaken by Chief Photographic Technician Amélie Deblauwe and processing of these images by Project Photographer Raffaella Losito in the University Library’s Cultural Heritage Imaging Lab. This has enabled Clarck Drieshen, who catalogued the manuscript, to recover the name of an early – possibly the earliest – owner of the manuscript: ‘Thomas Wort(es) leche’. The style of handwriting tells us that he was probably not the person responsible for copying the text of the manuscript, but that he must have written his name into the book soon after it was made. Nothing else is known about him – yet! – other than that he explicitly identified himself as a leech.

While most medieval manuscripts typically have been rebound or altered in other ways in modern times, MS Add. 9309 feels like it has emerged from a medieval time-capsule. This partly reflects how it has come down to us, with its medieval binding intact and its leaves heavily thumbed – but it also results from a thoughtful approach by the conservator. In making the manuscript accessible with an appreciation for both its original material features and historic signs of use, it can be read in virtually the same condition as it has been in for centuries. The principle of enhancing access through minimal intervention is further supported by photography: regular imaging with reflected light enables everyone to access the manuscript at a safe distance, with new imaging techniques enabling us to peer through layers of dirt and look even more closely at features that are not even legible to the naked eye.

A wonderful way to demonstrate “on the ground” medicine in medieval England AND the valuable methods by which this document is preserved!