‘By A Lady: A Hebrew-English dictionary by Abigail Lindo

By Tamar S. Drukker

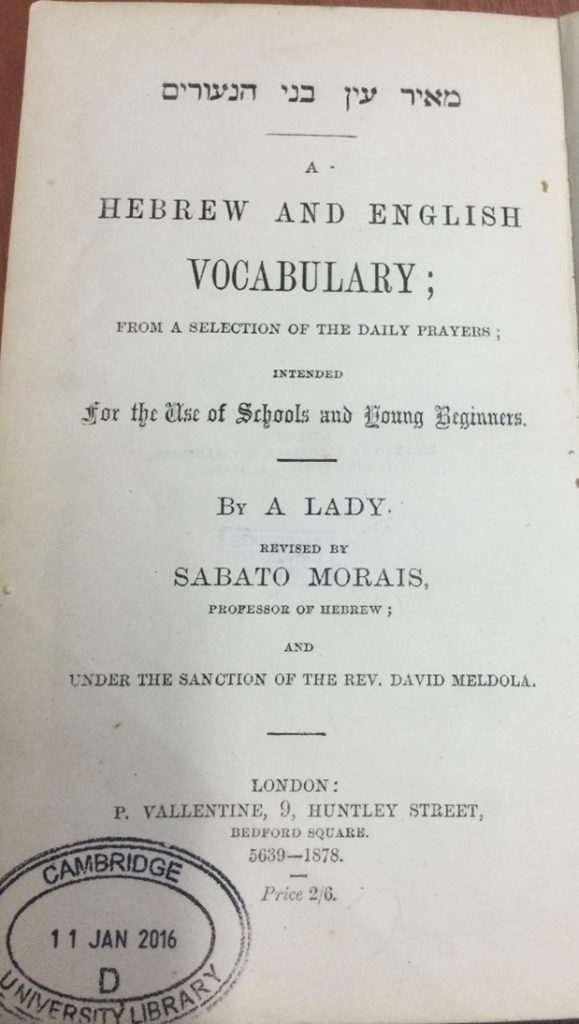

Among the many books left to the University of Cambridge by the late professor of Hebrew, Raphael Loewe (1919-2011) is a slim volume, just over a hundred pages, entitled A Hebrew and English Vocabulary. Loewe was a philologist, an expert in Semitic languages, especially Hebrew and Aramaic and a gifted translator, most notably of medieval Hebrew poetry from Spain. He was also a great lover of books; his rich collection ranges from early-printed sacred books from the sixteenth century in Hebrew, to a lexicon of Modern Hebrew blessings and curses compiled by Netiva Ben Yehuda, the author of the first dictionary of Hebrew slang.

What use would such an expert of Hebrew have with a small vocabulary which, as the subtitle suggests, was ‘intended for the use of schools and young beginners?’

Whereas the information contained within the book is useful for understanding the meaning of the daily prayers, the title page reveals a different story, that of one of the few nineteenth-century women lexicographers, Abigail Lindo.

The abridged book, revised by Rabbi Sabato Morais and printed in London in 1878 does not credit the author by name, simply attributes it to ‘A Lady’ as was the norm in England at the time. It might be shocking for modern readers, but neither Jane Austen nor the Brontë sisters, have seen their work in print under their own name. Jane Austen’s first published novel was Sense and Sensibility (1811), written ‘by a Lady.’ Two years later, in 1813, Pride and Prejudice was published with the attribution ‘by the author of Sense and Sensibility.’[1]

In May 1846, the Brontë sisters published a volume of poetry using male pseudonyms sharing their initials: Currer (Charlotte), Ellis (Emily) and Acton (Anne) Bell. They used the same names to publish their novels, as Charlotte explained:

Adverse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell; the ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women – without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called ‘feminine’ – we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice…[2]

However, as early as 1837, a book appeared in print in England with the name of the female author on the title page.

Cambridge University Library has a copy, presented by the authoress, of a later, extended edition, from 1846.

Abigail, the third daughter of David Abarbanel Lindo, was born in London in 1803 to Sarah (née Mocatta) and David Abarbanel Lindo, members of the Jewish Sephardi community. Her uncle, Moses Mocatta, taught her Hebrew and he encouraged her to publish a dictionary she had created as a study tool. She is the first Jewish woman to publish a dictionary and the first woman in Britain to have her name appear in print as the author. However, the title page only introduces her by her first name, followed by her father’s name and accompanied by his portrait. The publisher, Samuel Meldola, added a paratheatrical note, ‘not published,’ although the book clearly appeared in print in numerous copies and was intended for a wide readership.

The author signs with her full name the dedication page. In her preface she refers to herself several times as ‘the authoress,’ taking full responsibility for the content as well as the structure of the work.

It is a carefully-planned dictionary, spanning 359 pages, with cross references and notes on grammar. Abigail Lindo explains to her readers the structure and the method used for her dictionary:

The first part contains the words in most frequent use, arranged n alphabetical order, in Hebrew and English, with the roots attached to the Hebrew words… The second part consists of English and Hebrew, arranged alphabetically, shewing when each word occurs in the holy Bible… This part will be found to contain upwards of four thousand biblical references. The third part explains the abbreviations most frequently adopted in writing or printing.

With authorship comes authority, and Lindo asserts her responsibility for the work when she adds:

The Authoress begs to state, that she is fully aware her work will not be found free from error, but claims for herself the indulgence of her readers, and desires that it may be borne in mind, that she does not publish it with a view either to fame or gain; her object being to assist those who wish to study the sacred langue; and if that aim be attained, she will be amply repaid for the time and labour devoted to its compilation. The Authoress is fully sensible this volume may be greatly enlarged and improved, and hopes that some Hebrew scholar will undertake the task.

Abigail Lindo died in 1848, aged 45. Perhaps she may not have approved of the reduced and simplified version of her dictionary, published after death, and would prefer it was not attributed to her, but instead to ‘a Lady.’

Further reading:

A scanned copy of Abigail Lindo, A Hebrew and English and English and Hebrew dictionary with roots and abbreviations (London, 1846).

https://victorianjewishwritersproject.org/objects/vjwp_145.pdf

Morris, Shalom, ‘The wise son: the daughters of the London S&P Sephardi Community: lecture #1 – Abigail Lindo.’

https://www.sephardi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/The-Wise-Son-1.pdf

Rodrigues-Pereira, Miriam, ‘Lindo, Abigail (1803-1848),’ Oxford dictionary of national biography.

https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-70006

[1] https://janeaustens.house/jane-austen/timeline/

[2] https://blog.nls.uk/out-of-obscurity-i-came-to-obscurity-i-can-easily-return-charlotte-bronte-currer-bell-and-jane-eyre/