Peter Pan in the Tower

Post by Dr Sarah Pyke, Munby Fellow in Bibliography 2023/24, who is using the University Library’s legal deposit holdings (the Tower Collection) to survey illustrated dust jackets and covers of children’s books from 1910 to 1990. Booking is open for Dr Pyke’s free public talk on ‘Book history betwixt-and-between: Peter Pan in Cambridge University Library’s Tower Collection’ on Wednesday 29 May. Booking information here.

A few months ago, I was strolling down a London street when my attention was caught by a singular vehicle, brightly decked out in a decal livery: a mermaid sunning herself on a rock, a genial Captain Hook sporting a hot pink hat, a smiling crocodile, and the stylised figures of Tinker Bell and Peter Pan, bobble-headed and blank-eyed, suspended against a night sky. This is the Peter Panbulance, one of Great Ormond Street Hospital’s fleet of electric ambulances. Somewhat disconcertingly, it appears to have programmed its GPS with the route to Neverland, promising to deliver you to emergency care by driving ‘Second to the right and straight on till morning’.

‘Peter Panbulance’ may be a wince-inducing pun, but it’s also testament to how stubbornly J.M. Barrie’s most famous character has lodged itself in our cultural consciousness. More than an enduring fictional character, Peter Pan has given his name to an array of material things, including ‘a Golf Club, […] a stained glass window in St James’s Church, Paddington, and a 5000-ton Hamburg-Scandinavia car ferry’, as Jacqueline Rose points out, and, as Robert Douglas-Fairhurst adds, also to a psychological complex, a type of collar and a brand of peanut butter.

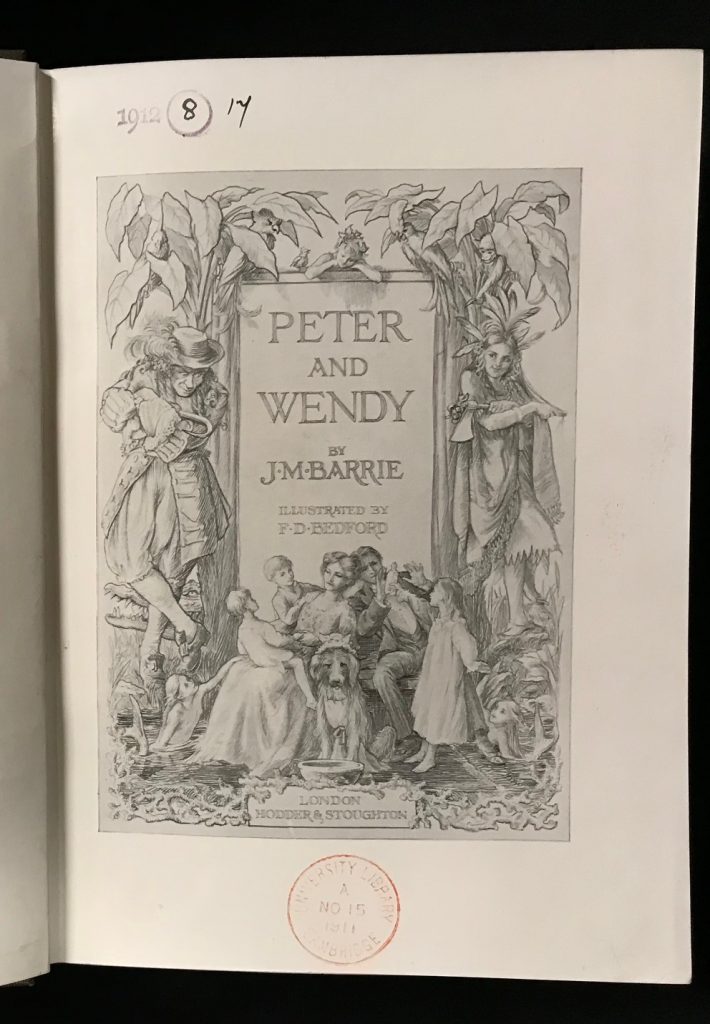

But if everyone knows Peter – cocky, charming, vain, tragic, protean – readers might be less familiar with Peter Pan’s publication history. It is as slippery as Peter himself. Peter first appeared in Barrie’s The Little White Bird (1902), a whimsical book with an implied adult readership, making a sideways move to the stage in 1904. The play proved popular; so much so that the chapters concerning Peter from The Little White Bird were extracted and published separately in 1906 as Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. Some five years later, in 1911, the novelised form of the stage play was published first under the title Peter and Wendy, as Peter Pan and Wendy from 1915, and then from 1939 also as Peter Pan.

These texts are book-ended by some more idiosyncratic works. Before The Little White Bird came the self-published The Boy Castaways of Black Lake Island, a 1901 book of photographs of Barrie’s young friends, the sons of Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies. The boys enact several scenes recognisable from later iterations of Peter Pan with commentary purportedly by the third-eldest boy, Peter Llewelyn Davies. Only two copies were printed. Following the 1911 novel, Barrie published the short story ‘The Blot on Peter Pan’ in 1926 and delivered the unpublished short story ‘Jas. Hook at Eton’ – a kind of personal fan-fiction – as a speech at Eton College in 1927. The text of the stage play Peter Pan finally appeared in 1928, with a long dedication to ‘the Five’: George, John, Peter, Michael and Nicholas Llewelyn Davies.

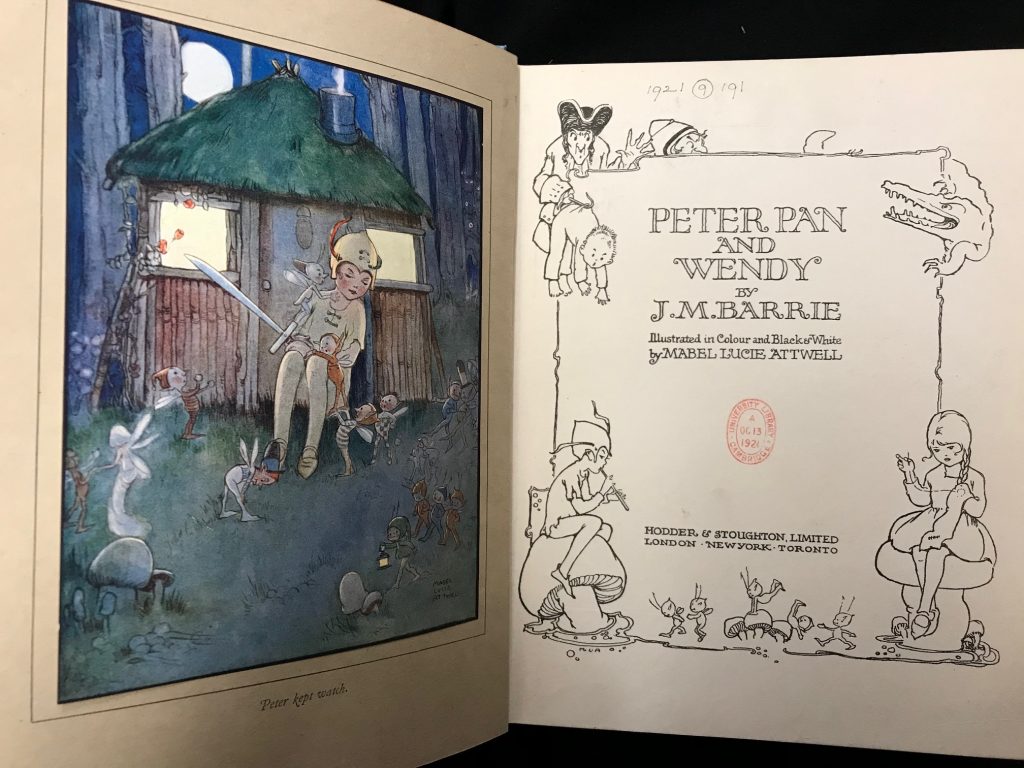

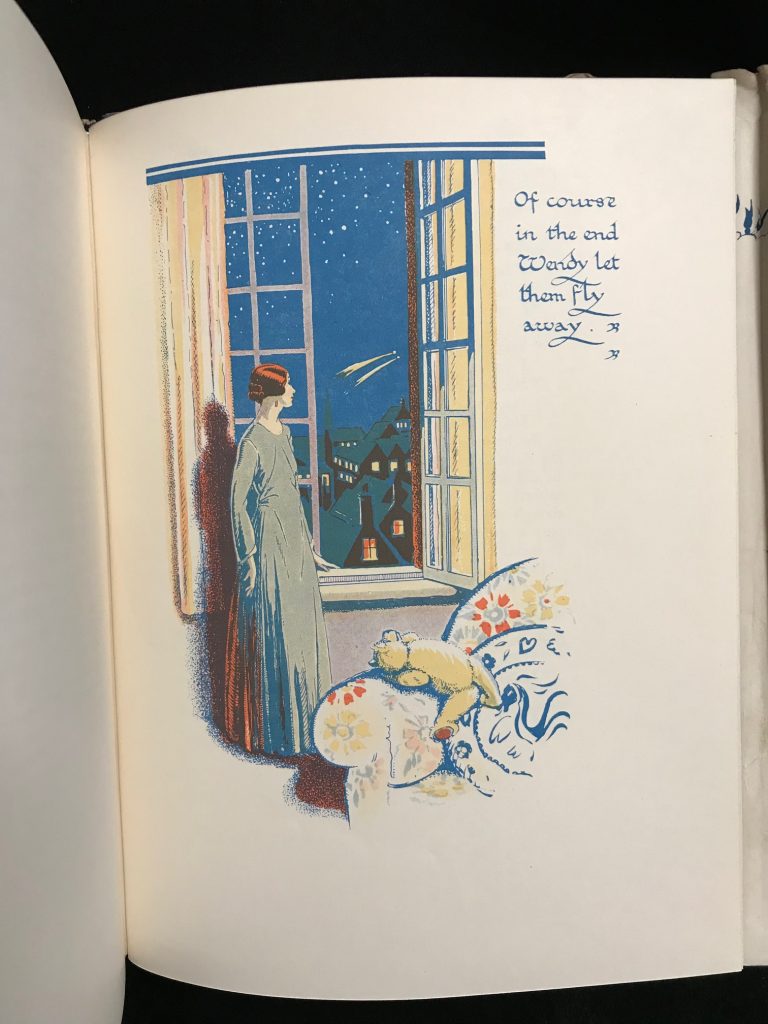

Barrie himself knowingly played with questions of authorship and creation. As Andrew Nash puts it, Barrie viewed ‘the story of Peter Pan’ as ‘a fluid, evolving myth, authored not solely by him but by the Llewelyn Davies boys as well, and indeed, by any other child (or adult) who engaged with the story’. Adaptations have flourished, from Disney’s 1953 film, to the Tinker Bell extended universe (DisneyToon Studios, 2008-2015). But if Barrie’s texts wriggle free from generic constraint, they have at the same time been pinned down in a variety of material forms. Less attention, however, has been given to the illustrators who have contributed to this visual iconography, bringing Peter Pan into focus in every decade of the twentieth century, and adjusting the picture slightly each time. To give just three examples, F.D Bedford’s eerie, magical half-tone plates for the 1911 edition were followed in 1921 by Mabel Lucie Attwell’s cutesy babies. Ten years later, Gwynedd M. Hudson’s fresh, busy illustrations update the story for a smart new decade, labelling characters and decorating the body-text with hand-lettered quotations. (Click image to enlarge.)

Appropriately enough, Peter Pan has been shadowed by other material incarnations from its conception. Rose puts it best: ‘J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan was retold before he had written it, and then rewritten after he had told it.’ The holdings of the University Library’s Tower Collection, assembled via legal deposit, mean that not only are the canonical works presented above – Barrie’s own – shelved in remarkable condition, some complete with dust-jackets (which is rare for an institutional library), but that many other ephemeral publications surrounding Peter Pan are available to the curious.

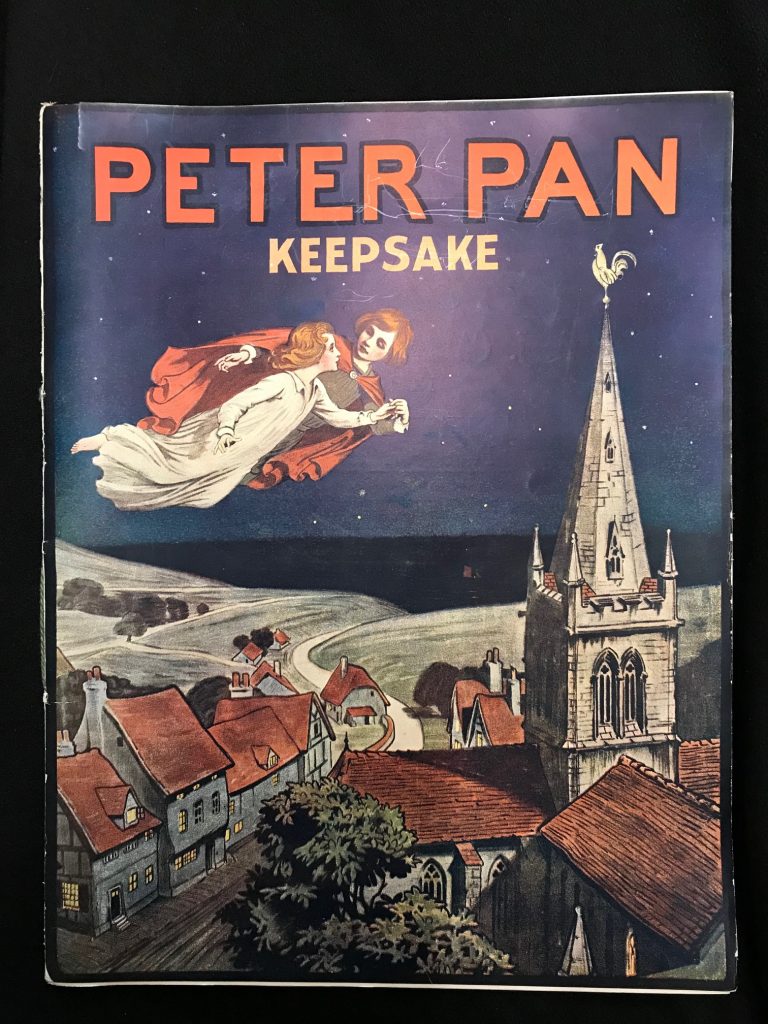

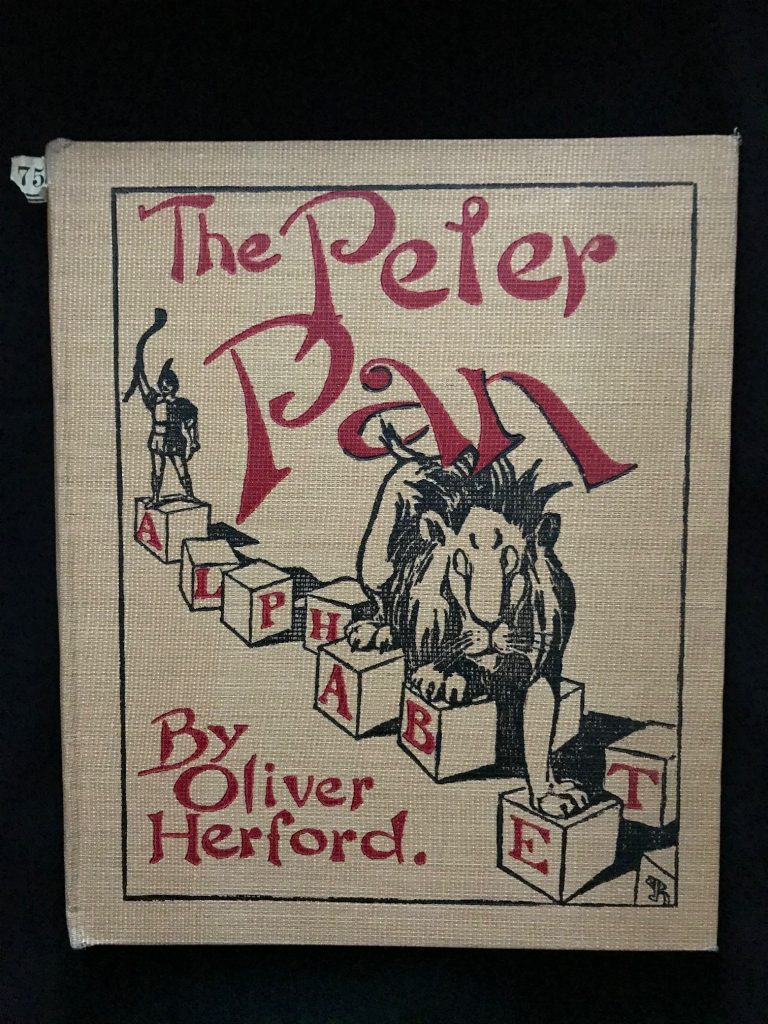

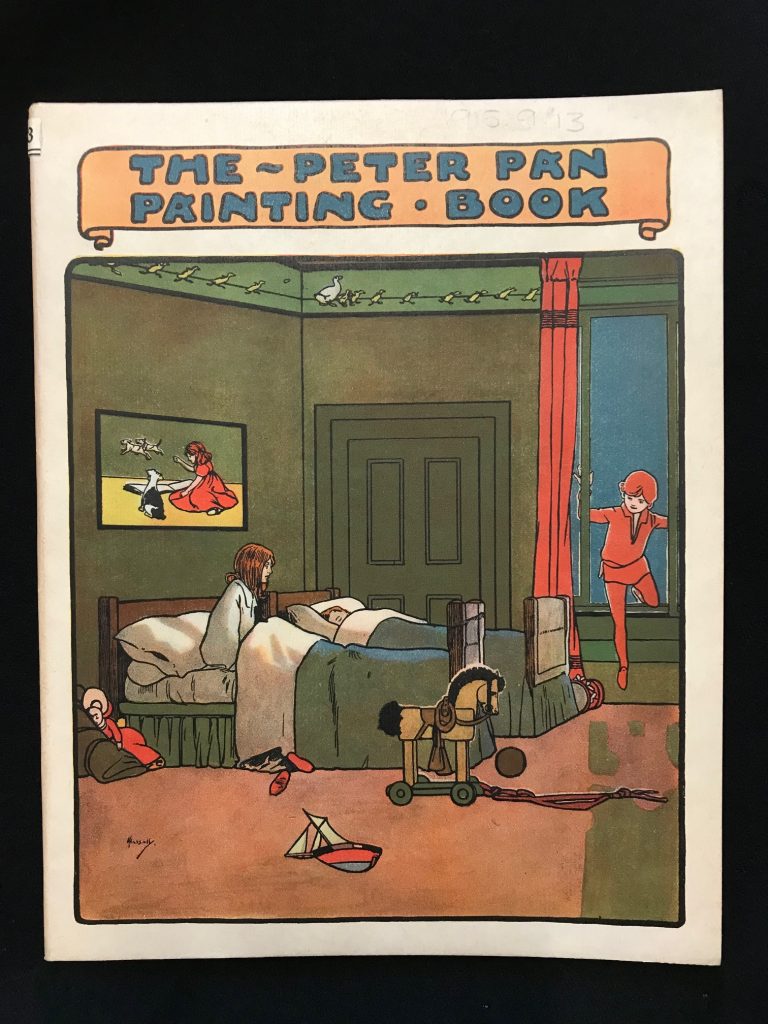

Here is D.S. O’Connor’s Peter Pan Keepsake, illustrated by Alice Woodward and published by Chatto and Windus in 1907. A large-format, softbound book, it is a memento for audiences of the stage play, with a retelling of the story in prose. Oliver Herford’s ABC, again from 1907, finds an appropriately themed noun for every letter of the alphabet – ‘C is for the Crocodile Creepy who ate / The right hand of Hook and covets its mate / He makes a loud ticking wherever he goes / For he swallowed Clock (to kill time I suppose)’. Children from the mid-1910s onwards could create their own version of the storywith John Hassall’s The Peter Pan Painting Book. It features facing-page illustrations in full colour and in black outlined on white, for readers to copy or colour as they wish. The drawings attend closely to the material culture of Edwardian childhood and the architecture of the upper middle-class home. These are just some of the tie-in and spin-off publications that contribute to making Peter Pan ‘a children’s classic before it was a children’s book’ (Rose, again).

Attentive readers of the wider Peter Pan oeuvre may spot Barrie’s own preoccupation with the materiality of writing: with inkblots and rubbings-out and scrawl and lettering. In the opening chapter of Peter Pan, for example, Mrs Darling is engaged in her nightly practice of ‘tidying up her children’s minds’, when her attention is arrested by a ‘most perplexing word’, which ‘stood out in bolder letters than any of the other words’, and had ‘an oddly cocky appearance’. The word, of course, is ‘Peter’. While critic Peter Hollindale has commented that ‘the prose texts of Peter Pan are very complex works that we are still learning how to read’, there’s a case to be made, I think, that reading Peter Pan as a material text helps us in this task. Without proper attention to its various papery incarnations, a wholly satisfying explanation for its extraordinary staying-power will remain elusive. Peter will continue to slip through the fingers of critics and readers alike.