Strength in adversity: The hidden stories of two Cambridge Martins

Guest post by Matt Ryan, an AHRC-funded PhD candidate at Newcastle University. His research focuses on the relationships between printers, publishers, booksellers, and writers in the late sixteenth century.

If you wanted to buy a book in late sixteenth-century London, St. Paul’s churchyard was the place to go. Stood at the yard’s north gate, today’s visitors are met with sloping paths and landscaped gardens. Four hundred and thirty years ago, this open space was a warren of bookshops. Clustered around buildings, stuffed between buttresses and lining perimeter walls, they were everywhere you looked.[i] In and around these bookshops, crowds of early modern shoppers combed through piles of books and shared gossip about the latest titles. At the end of the 1580s, the name on everyone’s lips was Martin Marprelate.

The Marprelate tracts are a series of six pamphlets and a broadsheet printed on a secret press between 1588 and 1589. They take aim at the Elizabethan church, and argue on behalf of an alternative, Presbyterian system. Willing to shout, name names and poke fun at his enemies, Martin’s voice was worlds away from the often restrained tone of reformist polemic, and its appearance in print triggered an almost immediate response from church and state: the tracts were banned, and an exhaustive search undertaken to snuff out those responsible. By the autumn of 1589, Martin’s printers had been rounded up, racked, and imprisoned. Under attack from all sides, the Marprelate agents still managed to print one last pamphlet: The Protestation of Martin Marprelate.

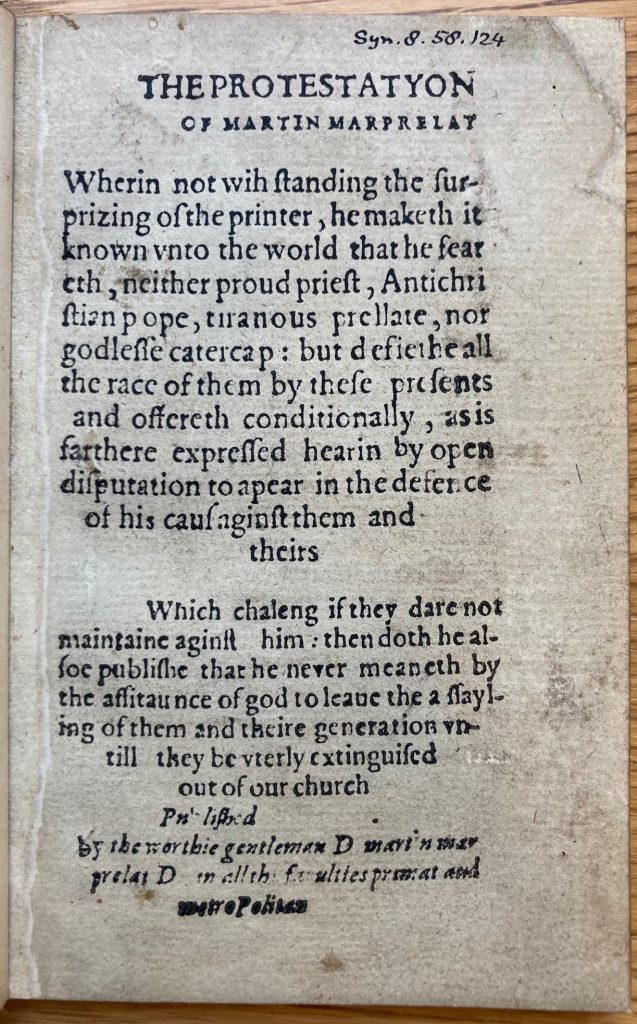

With the Marprelate printers arrested, their press and type confiscated and several co-conspirators too terrified to help, Protestation emerged in straitened circumstances. Inexpertly produced on an old press stowed in a barn on a Coventry estate, this final tract was likely set by Martin’s co-authors Job Throckmorton and John Penry. The Cambridge University Library copy of Protestation (Syn.8.58.124) tells the story of these chaotic conditions. Across the first gathering, the justification is hopelessly crooked, words are misspelt and letters appear reversed (Figure 1). Gaps appear throughout, catchwords disappear, and typefaces shift unexpectedly.

The quality of the printing unexpectedly improves in the third gathering. We know, from the courtroom testimony of Henry Sharpe, Protestation’s binder, that toward the end of August, Robert Waldegrave, another of the Marprelate printers, reemerged from hiding to lend a hand. [ii] We can reasonably assume that the third gathering marks Waldegrave’s return to the press, and from here, page justification evens out and the quality of each impression is noticeably clearer.

At the start of September, Martin’s pursuers closed in, and Humphrey Newman, the tracts’ main distributor, journeyed to Coventry to pick up a final batch of pamphlets. By the time The Protestation hit the shelves of St. Paul’s, Martin’s remaining collaborators had been arrested, and the Marprelate project was silenced. But, not for long.

In Hay any Work for Cooper (1589), Martin taunts his opponents, warning that ‘the day that you hang Martin, assure yourselves, there will be twenty Martins spring in my place.’[iii] A glance at his afterlife proves this prophecy true. While the anti-Martinist campaign was successful in suppressing Martin’s voice in the years immediately following the arrest of those involved, the Marprelate brand was invoked in anti-episcopal tracts from the 1620s and again in several pamphlets printed during the Civil War years.[iv] A sammelband held in St. Catharine’s College library sheds light on what drew these readers to Martin.

While the identity of Martin’s authors was at first shrouded in mystery, Penry’s execution and Throckmorton’s escape into obscurity saw the rumours of their involvement more-or-less confirmed by the 1610s. In the St. Catharine’s volume (D.11.77) the final three Marprelate tracts are bound with Throckmorton’s M. Some laid open his coulers (1589) and Penry’s A view of some part (1589). This deliberate act of curation suggests that the compiler knew of both men’s involvement with the Marprelate project, and we can reasonably assume that this volume forms part of Martin’s late career resurgence. Filled with detailed marginalia, D.11.77 both offers us a glimpse of how closely Martin was read and suggests that his later readers were particularly drawn to the message of community resilience explored in the tracts.

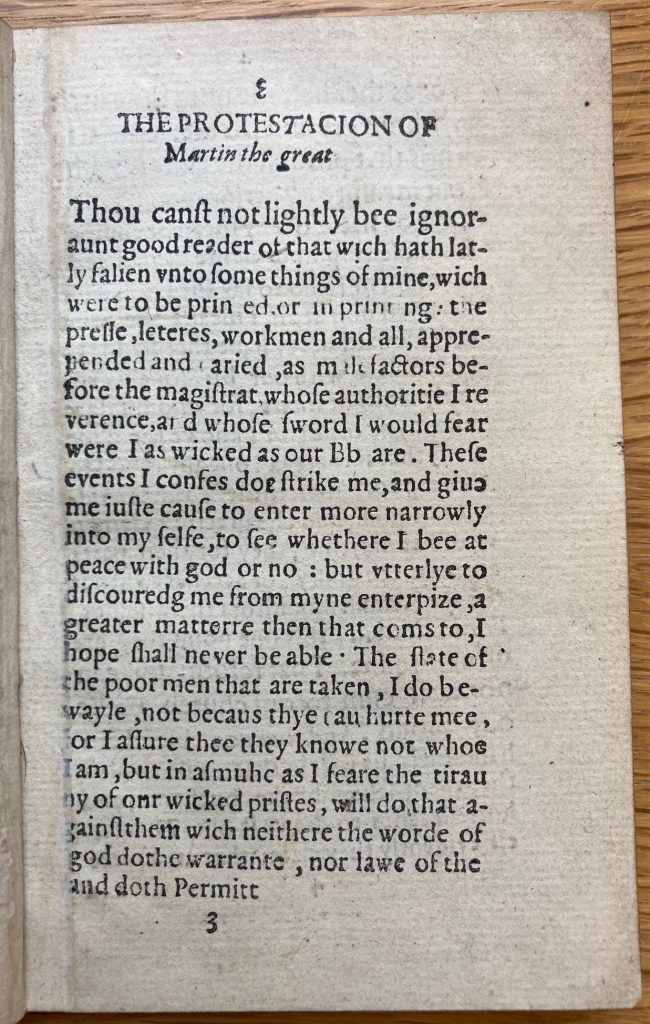

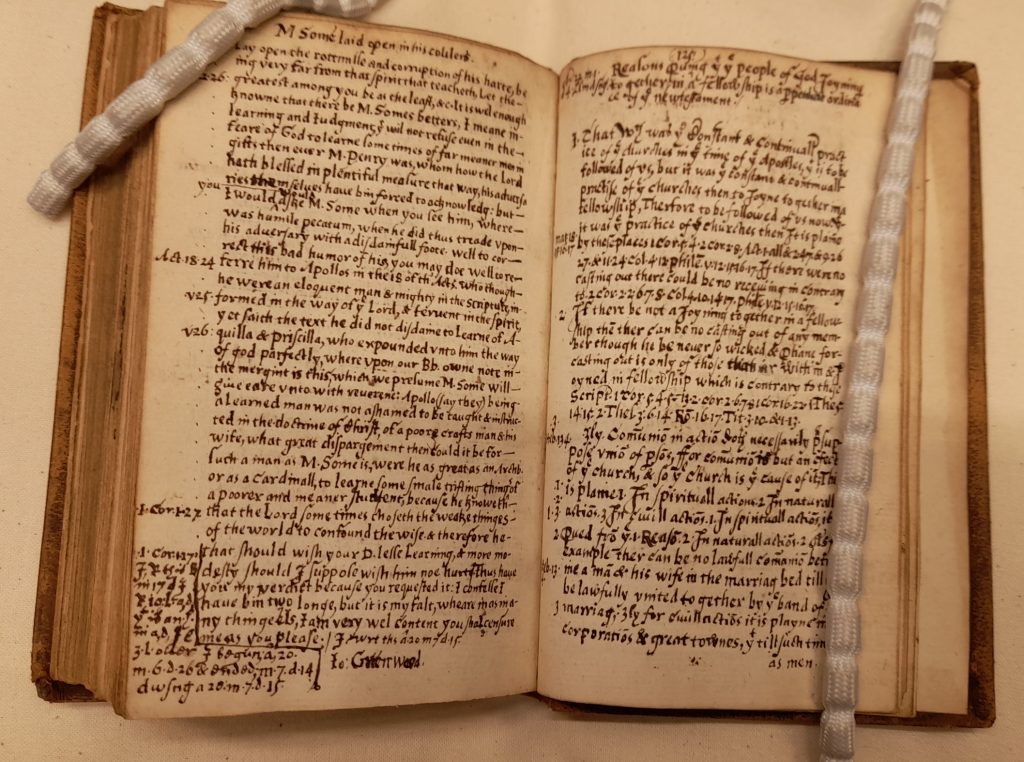

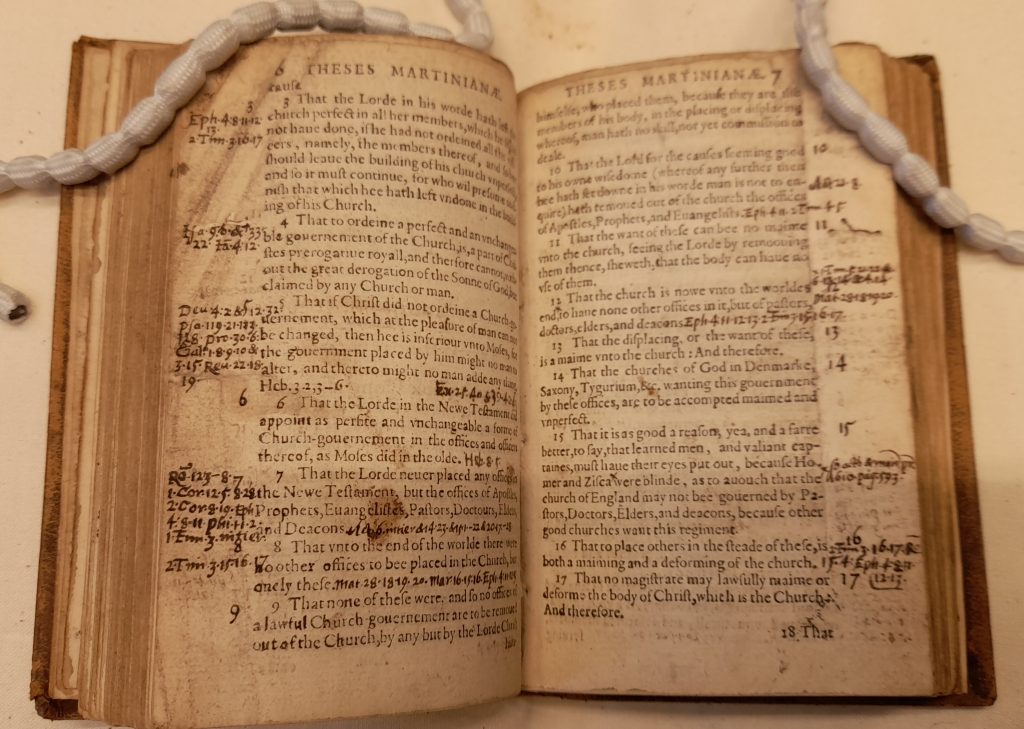

Exhaustive biblical references fill the margins, connecting passages of the Marprelate tracts with specific verses related to Christian brotherhood (Figure 4). These marginalia also function as intra-textual cross-referencing tools, directing readers to mentions of community ethics elsewhere in the volume (Figure 2). These fastidious reading practices culminate, at the back of the book, in two pages of autograph notes. Centred on the importance of ‘ye people of God joyning together in a fellowship’ (Figure 3), these notes bring together references from each of the sammelband’s texts, alongside dozens of biblical citations.[v] Marked clearly with its own heading and organised by marginal numbers, this section is neatly marked off from the rest of the book and its presentational clarity suggests that these notes were designed to be read by others.

In fact, with such close attention paid to the creation of the whole volume, it is possible that it was deliberately prepared for circulation. Where page numbers, sections of text or printed marginalia are missing, they have been added by hand, the binding is strengthened in places and detailed notes stuff the margins of each of the texts (Figure 2). In the same, painfully neat hand, errata listed at the back of the fifth Marprelate tract (Theses Martinianae) have been amended at the relevant points in the pamphlet.

Offering us an insight into Martin’s final weeks and his afterlife, both of these volumes tell the story of Martin’s resilient community of supporters. The collaborative struggle to print Protestation is revealed in the fabric of the text itself, while St Catharine’s sammelband allows us access to the constellation of readers who pored over its pages decades later. Tellingly, the marginalia and autograph notes included in D.11.77 suggest that Martin was also read for his discussion of the importance of community. While these insights emerged from the turbulence of Elizabethan England, they would no doubt still have been relevant to sympathetic readers living through the similarly volatile Caroline period. As such, the content, form, and use of both of these books discuss and construct the kind of resistant community Martin imagines.

[i] Samuel Rowlands, VVell met gossip; or, ‘Tis merry when gossips meet (London, 1656), sig. B3v.

[ii] Deposition of Henry Sharpe (15 Oct. 1589), British Library, Lansdowne MS 830/14, fol. 15r

[iii] Martin Marprelate, Hay any Work for Cooper (Coventry: Robert Waldegrave, 1589) sig. E3r

[iv] Joseph Black, ‘The Martin Marprelate Tracts (1588-89) and the Popular Voice,’ History Compass (vol 6, no 4) p1110.

[v] ‘Beza on the Church,’ D.11.77, St Catharine’s College library, Cambridge (pp.70-71)