An empire of literature: A new collection of colonial publications shows how British culture travelled the globe

Guest post by Dr Jacqueline Reiter, an independent historian specialising in late 18th and early 19th century British political, military and naval history. Jacqueline received her PhD from Cambridge in 2006 on the role of British national defence during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. As a volunteer at the University Library she has recently catalogued the collection which this blog discusses.

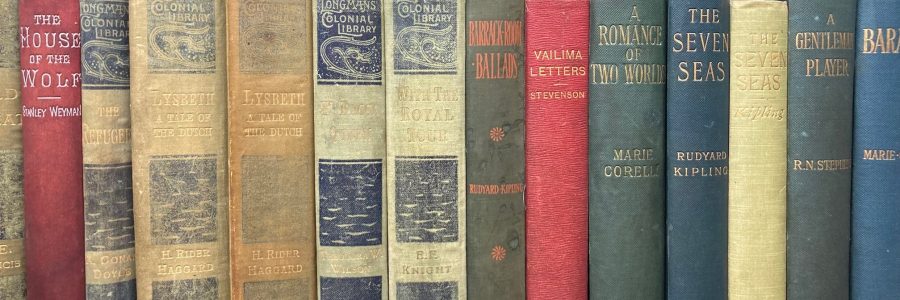

Rudyard Kipling, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie – all are familiar names, known for novels that have stood the test of time. Marie Corelli, Kate Douglas Wiggin and Ralph Boldrewood are less well known, while the name ‘Winston Churchill’ probably does not conjure up the image of an early twentieth-century novelist. All these authors nevertheless appear together within a selection of nineteenth- and twentieth-century colonial editions of British literature recently acquired by the Library. The collection, comprising over 200 works of fiction and non-fiction published between 1843 and 1963, has been donated to the Library by Professor David McKitterick, former Librarian and Vice-Master of Trinity College. It sits in the Rare Books Room at the class CCC.79.

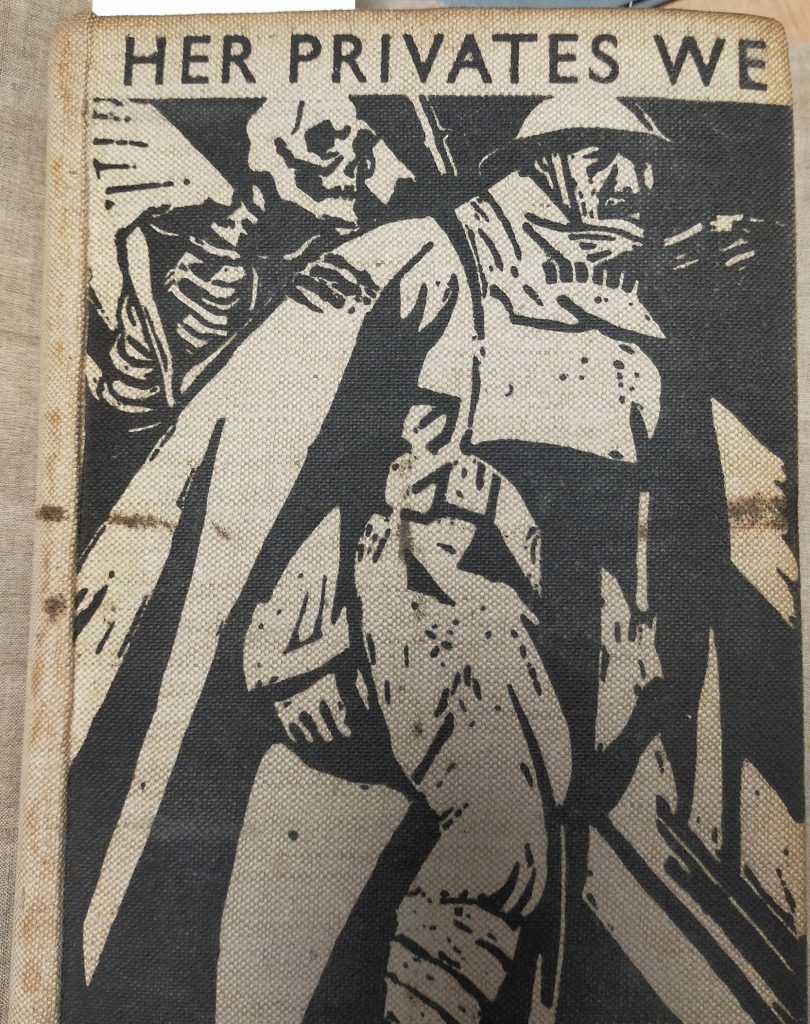

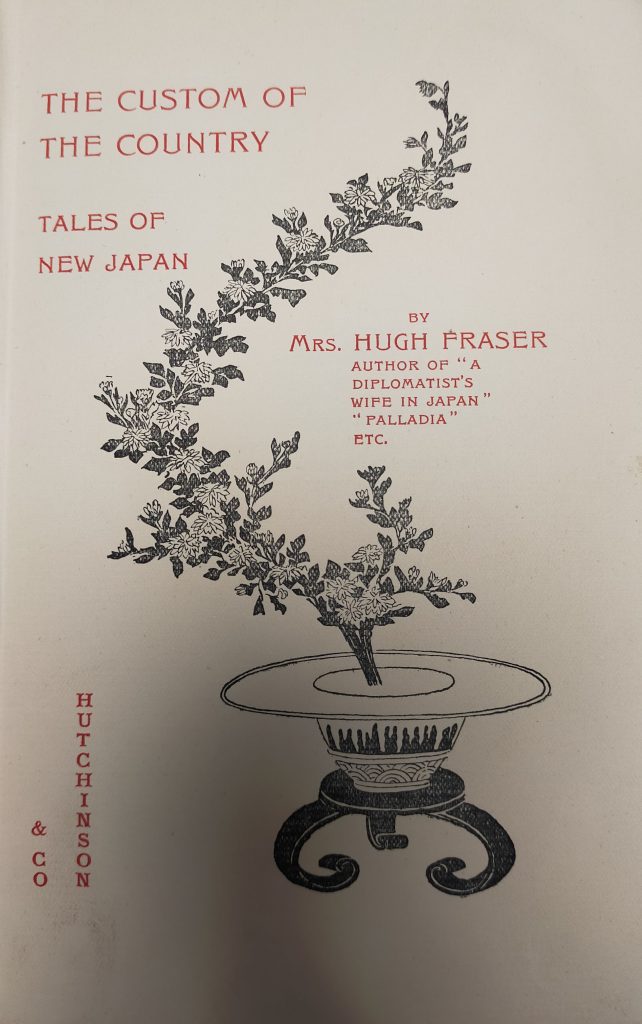

What distinguishes the collection is that it consists of books published only for sale in the British colonies. As such, it demonstrates what publishers considered interesting to a colonial audience, and represents a microcosm of what was considered popular literature at the time. The books were printed for mass audiences, with plain bindings and cheap paper, although some – particularly Mrs Hugh Fraser’s The Custom of the Country (CCC.79.178), and Her Privates We (CCC.79.206) by ‘Private 19022’, the pseudonym of Frederic Manning – are striking in their decorative covers and title page design. Most are works of fiction, but there is also some non-fiction, including religious commentary (Reginald Campbell’s New Theology [CCC.79.108]), historical essays (J.R. Seeley’s Expansion of England [CCC.79.64]) and travel narratives (Frederick Nansen’s Farthest North [CCC.79.32–33]).

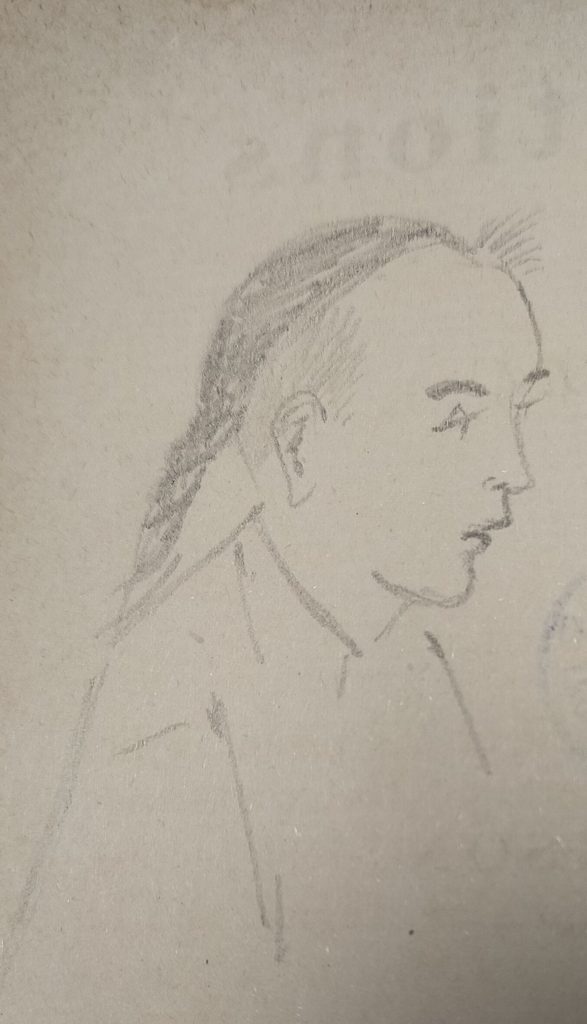

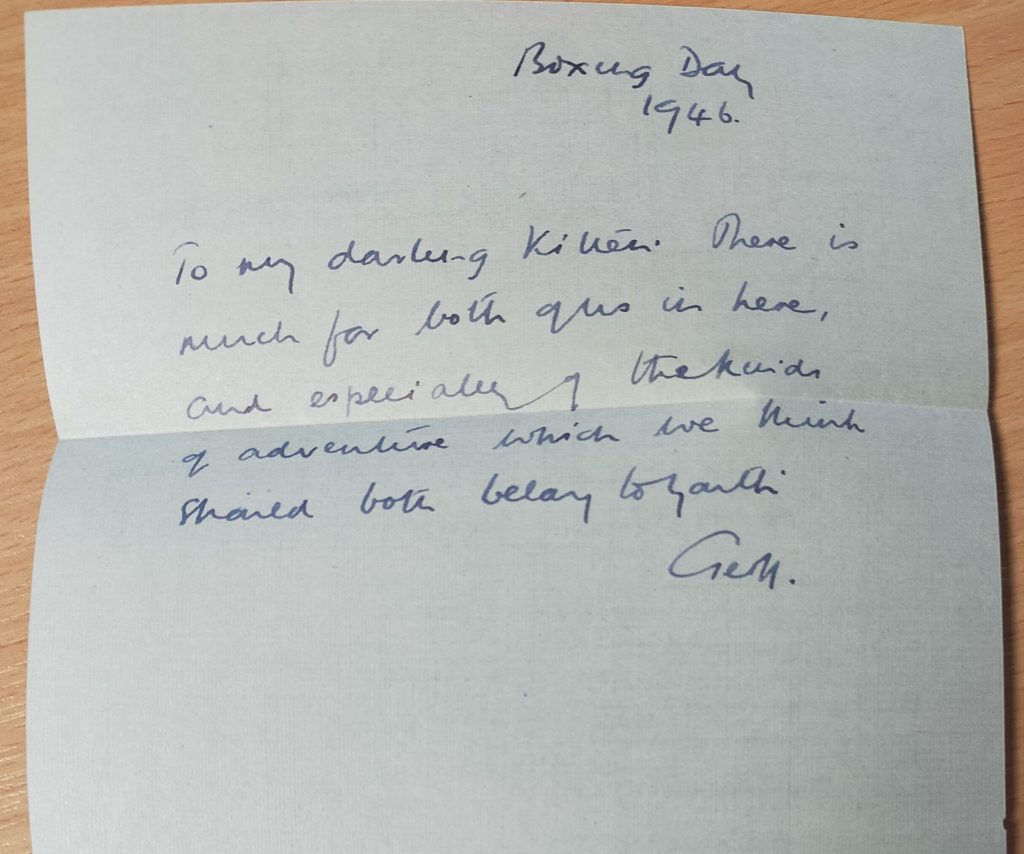

Another interesting aspect of the collection arises from the former owners of the books. Many left a variety of bookmarks in situ – newspaper cuttings, adverts for life insurance, a care label cut from a coat, a leaf. One reader scribbled a hasty portrait on the copyright page (CCC.79.91). Another received one of the books (CCC.79.208) as a late Christmas present, along with a note from a husband or lover: ‘To my darling Kitten’, signed by ‘Geoff’. Neither ‘my darling Kitten’ nor ‘Geoff’ can be easily identified, but the former owners of more than half of the books in the collection can. Nearly twenty of the books, about one in ten, bear the name of Edmund Cecil Clifton (1883–1971), Registrar of Titles in Western Australia, and a further eight books come via the South African Public Library, Cape Town. These copies also come with the stamp of Hammersmith and Fulham Public Libraries, a reminder of how far books – and people – could travel while remaining within the confines of the British Empire. Exactly how much Britain was the centre of an expansive global network is suggested by an inscription in another book (CCC.79.167): ‘S.S. Zealandia, 19.4.11.’ S.S. Zealandia, an Australian-built steamship, was sailing around the Canadian coast during the late spring of 1911.

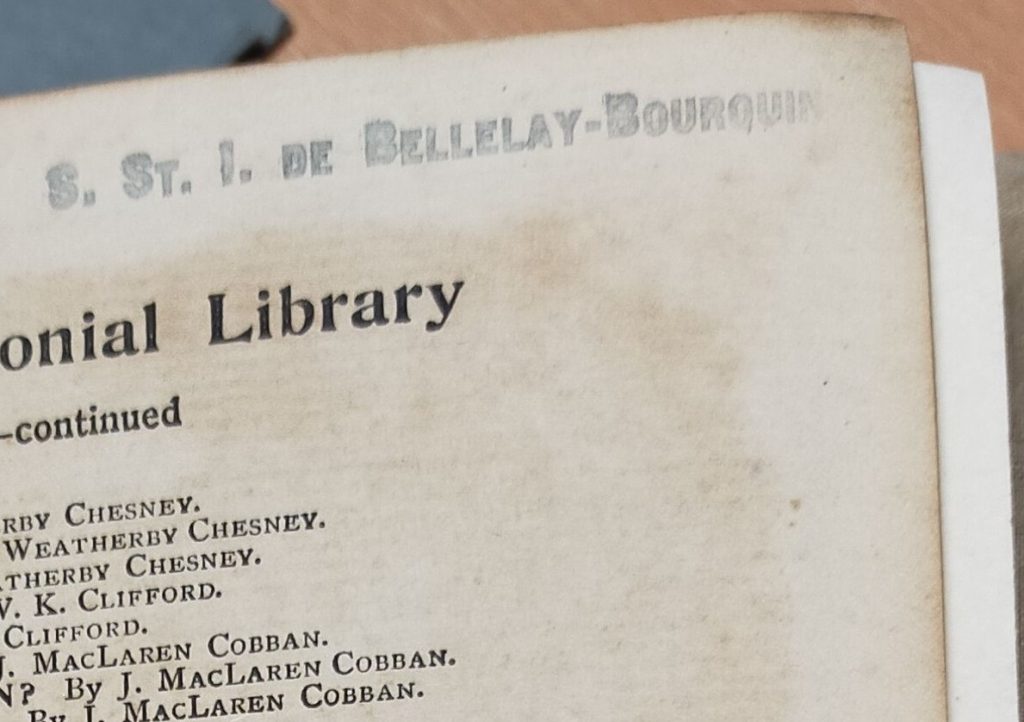

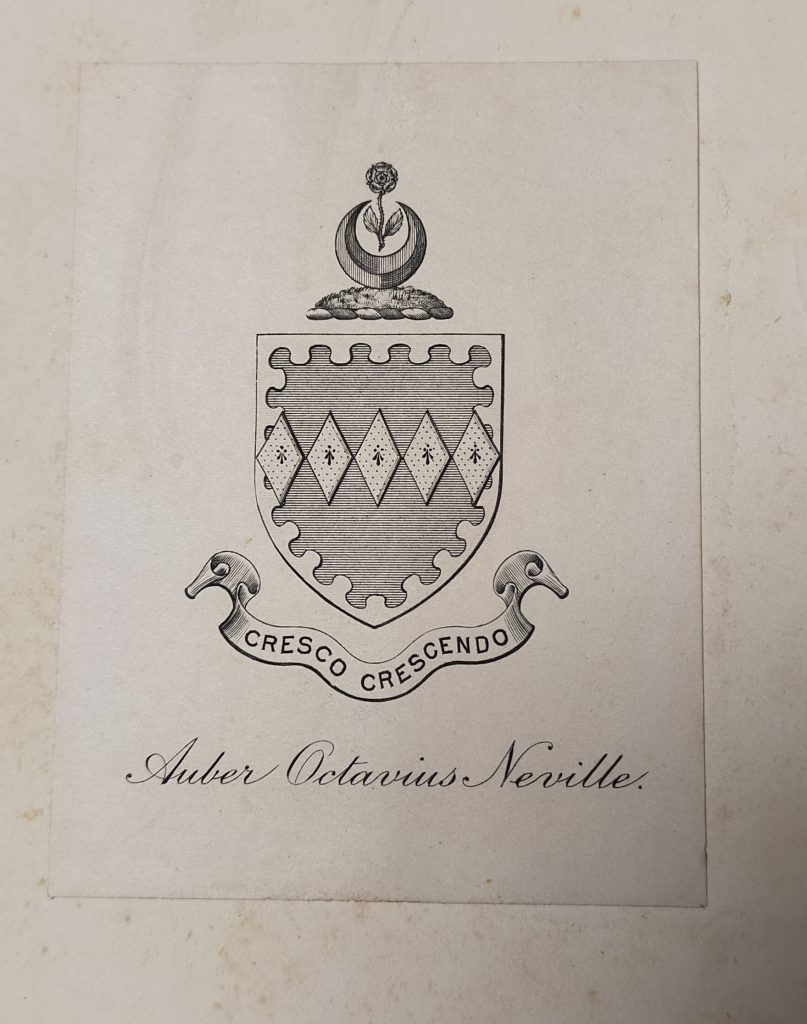

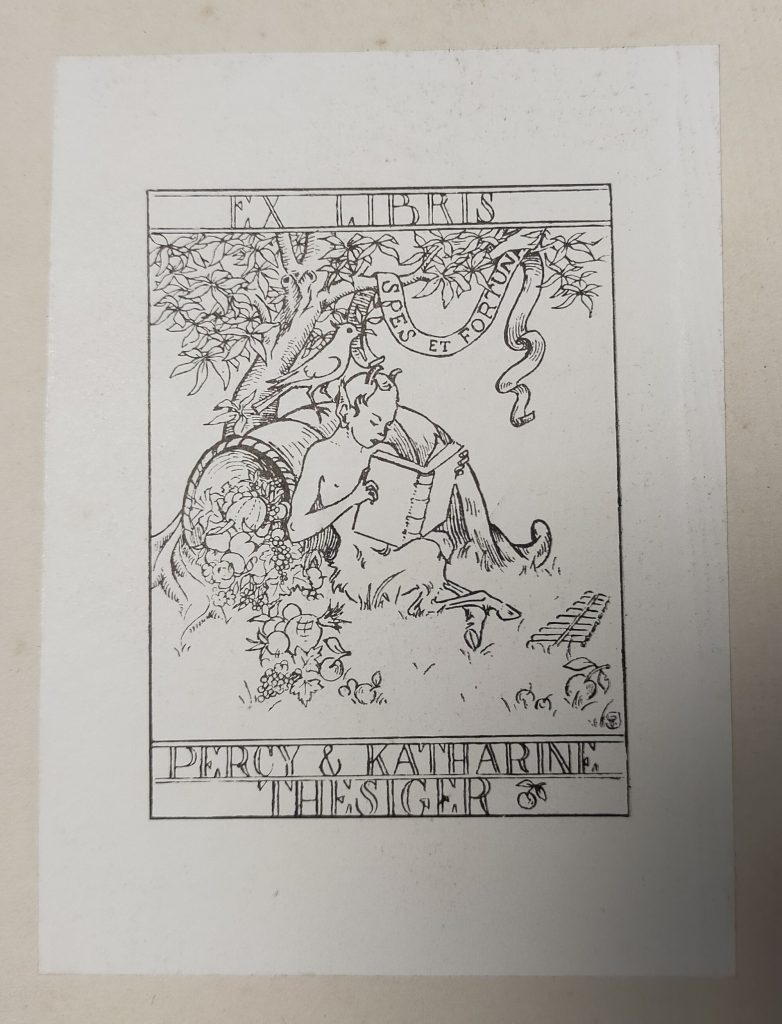

The names of other former owners, however, point to the more difficult legacy of colonialism. Sighart St Imier de Bellelay Bourquin (1914–2004), who owned Dietlof van Warmelo’s Boer war memoir On Commando (CCC.79.139), was Director of Bantu Administration in Durban, South Africa, between 1950 and 1973 under the Apartheid regime and oversaw the forced removal of Black residents. Auber Octavius Neville (1875–1954), former owner of Elizabeth Balch’s An Author’s Love (CCC.79.15), was Chief Protector of Aborigines and Commissioner of Native Affairs in Western Australia, where his policies reflected his belief in eugenics. And Percy Mansfield Thesiger (1869–1959), whose bookplate appears in E.F. Benson’s Limitations (CCC.79.91), was the younger brother of the 1st Viscount Chelmsford, Viceroy of India at the time of the 1919 Amritsar Massacre.

These are not pleasant associations, but they help explain why this collection will be particularly interesting to bibliographers and historians alike. Such factors lend tangibility and historical reality to a collection of books originally printed with the purpose of spreading British culture affordably and accessibly through an empire spanning the entire globe.