A Cure from the Crypt: Weapon Salve in the Library of John Dee

The astrologer, occultist, and alchemist John Dee (1527–1609) has long been associated with the art of necromancy – conjuring the spirits of the dead – but a newly digitised medical manuscript in the Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries project suggests that his interest in the dead may also have been of a medicinal nature. A manuscript from his library includes a previously unnoticed recipe for making a medicinal ointment for curing wounds that claims that it can heal patients at a thirty-mile distance. Instead of applying the medicine directly to the wound, the medical practitioner needs to apply it to the bloodied weapon that caused it, or, in its absence, an object made from a similar material to the weapon after it has been dipped into the wound. More extraordinary still, the medicine requires various ingredients extracted from corpses: skull moss, human fat and blood, and powdered mummy.

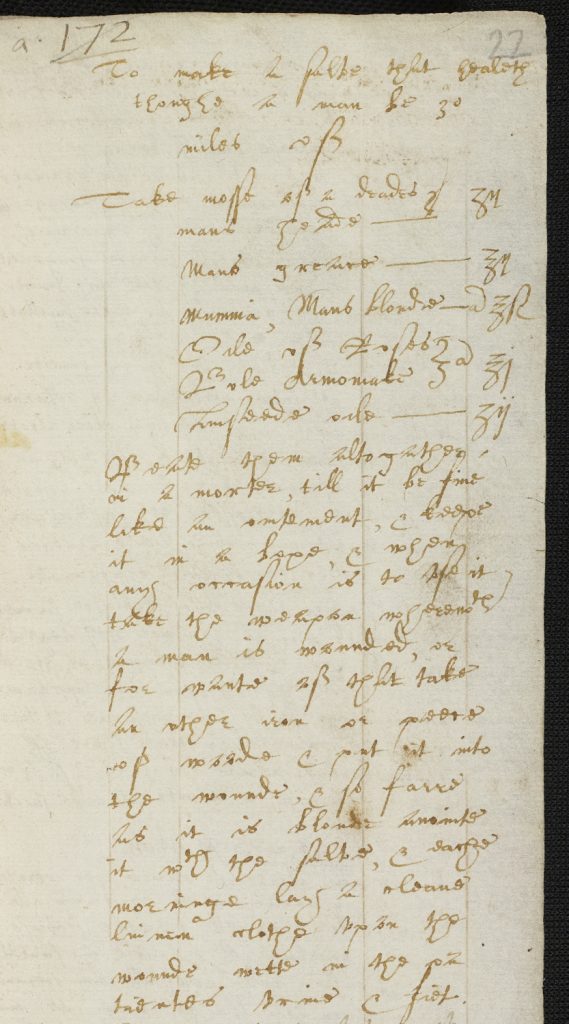

To make a salve that healeth though a man be 30 miles of

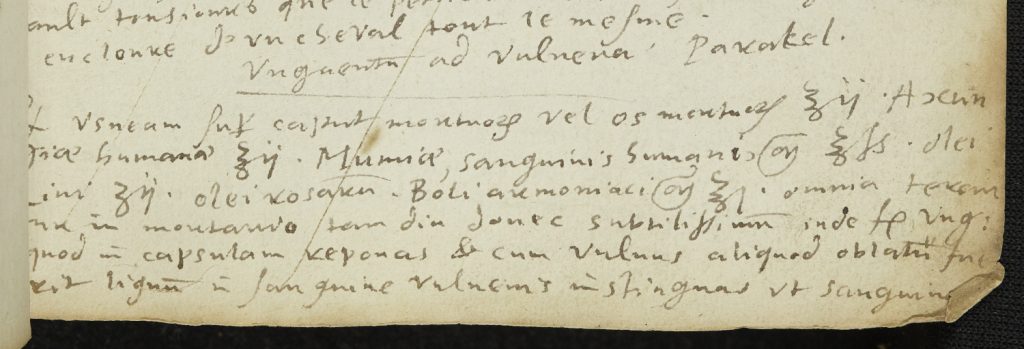

Take mosse of a deades mans heade – ʒij / Mans greace – ℥ij / Mummia, Mans bloude – ana ℥s / Oile of Roses – Bole Armoniake – ana ℥j / Linseede oile – ʒij / Beate them alto gather in a morter, till it be fine like an ointement, and keepe it in a boxe, and when any occasion is to vse it take the weapon wherewith a man is wounded, or for wante of that take another iron or peece of woode and put it into the wounde, and so fare as it is bloude anointe it with the salve, and eache morninge lay a cleane linen clothe vpon the wounde wette in the patientes vrine

To make a salve that heals [a wound] even if a person is thirty miles away:

Take two drams of the moss from a dead human’s head; two ounces of human fat; half an ounce each of mummy and human blood; one ounce each of oil of roses and Armenian bole; and two drams of linseed oil; grind them all together in a mortar until the mixture is fine like an ointment, and keep it in a jar, and when there is a reason to use it, take the weapon with which a person has been wounded, or, in its absence, take another piece of iron or wood and put it into the wound, and as much as it is bloodied you should anoint it with the salve, and each morning lay a clean linen cloth on the wound wetted in the patient’s urine

The gruesome recipe found in John Dee’s manuscript was well known in the early modern period. Known as ‘weapon salve’ (unguentum armarium), it was at the centre of a heated debate in which the Calvinist physician Rudolph Goclenius (1547–1628) defended the salve, explaining that it operated through magnetic powers between the weapon and wound that travelled via the stars, whereas the Jesuit priest Jean Roberti (1569–1651) attributed its efficacy to demonic powers. One of Roberti’s English supporters was William Forster (1591–1643), who likened the salve to a witches’ ointment.

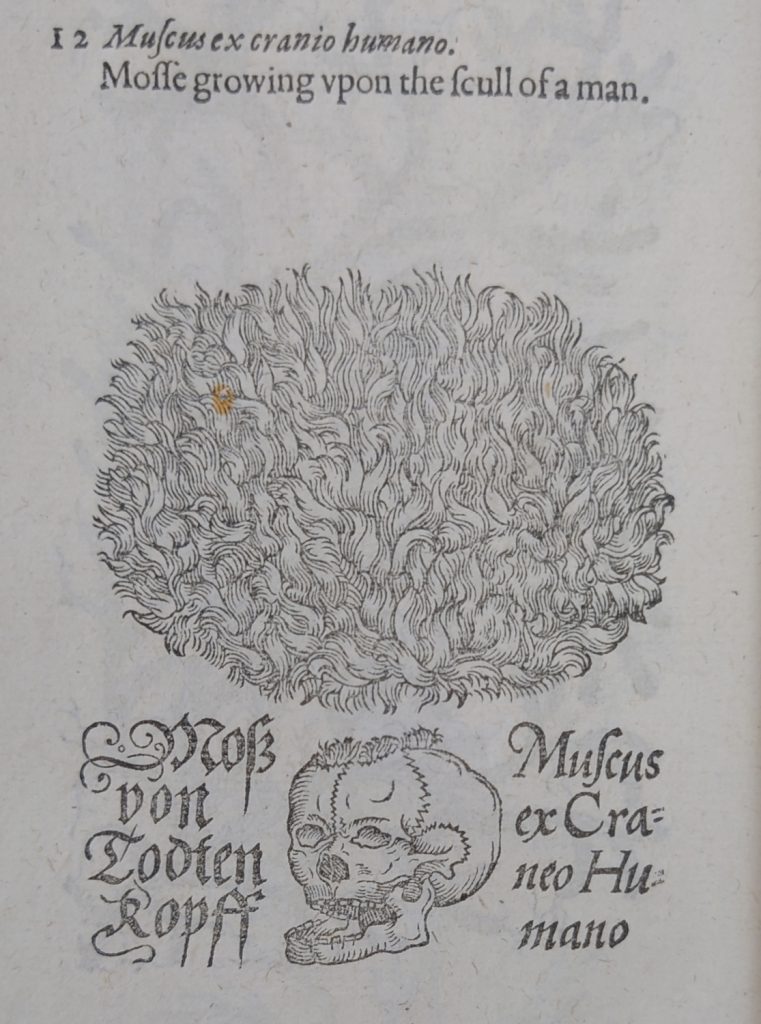

While this recipe may seem unusual, its corpse-derived ingredients were commonly used in early modern medicine. Skull moss, also known as usnea, was first recommended for medicinal purposes in the sixteenth century. In The herball or Generall historie of plantes (1597), the botanist John Gerard (c. 1545–1612) explains that this kind of moss is ‘found upon the scull or bare scalpes of men and women, lying long in charnell houses, and other places where the bones of men are kept togither’. He recommends it for treating epilepsy and whooping-cough in children: ‘it is thought to be a singular remedie against the falling evill, and the Chincough in children if it be powdered, and then given in sweet wine, for certaine daies togither’. Belief in the efficacy of skull moss relied on the idea that the human spirit of life or quintessence is stored in bones – as suggested by their long durability and the continued growth of nails and hair after death – and the skull in particular. The moss that was found growing on skulls was theorised to have obtained this spirit through magnetic and celestial forces.

Compared to skull moss, mumia had a much older medicinal tradition. Medieval Arab physicians had long prescribed mumia (from the Persian word mūmiyā for ‘wax’) for a host of ailments. The mumia they were referring to was a bitumen that seeped from rock-asphalt on a particular mountain in the Darabgerd area of Persia. However, in the twelfth century, mumia’s meaning changed. Gerard of Cremona (c. 1114–1187), in translating the works of the Persian physician Abū Bakr al-Rāzī [Rhazes] (865–925), and Matthaeus Platearius (d. 1161?), expanding on the work of Constantinus Africanus (d. 1087), both defined mumia as the liquid of the dead mixed with herbs such as aloes and myrrh, referring to a dark resin found on embalmed corpses. This new definition then took hold in medieval European medicine and created a demand among physicians and apothecaries for Egyptian mummies that could be ground up for medicinal purposes.

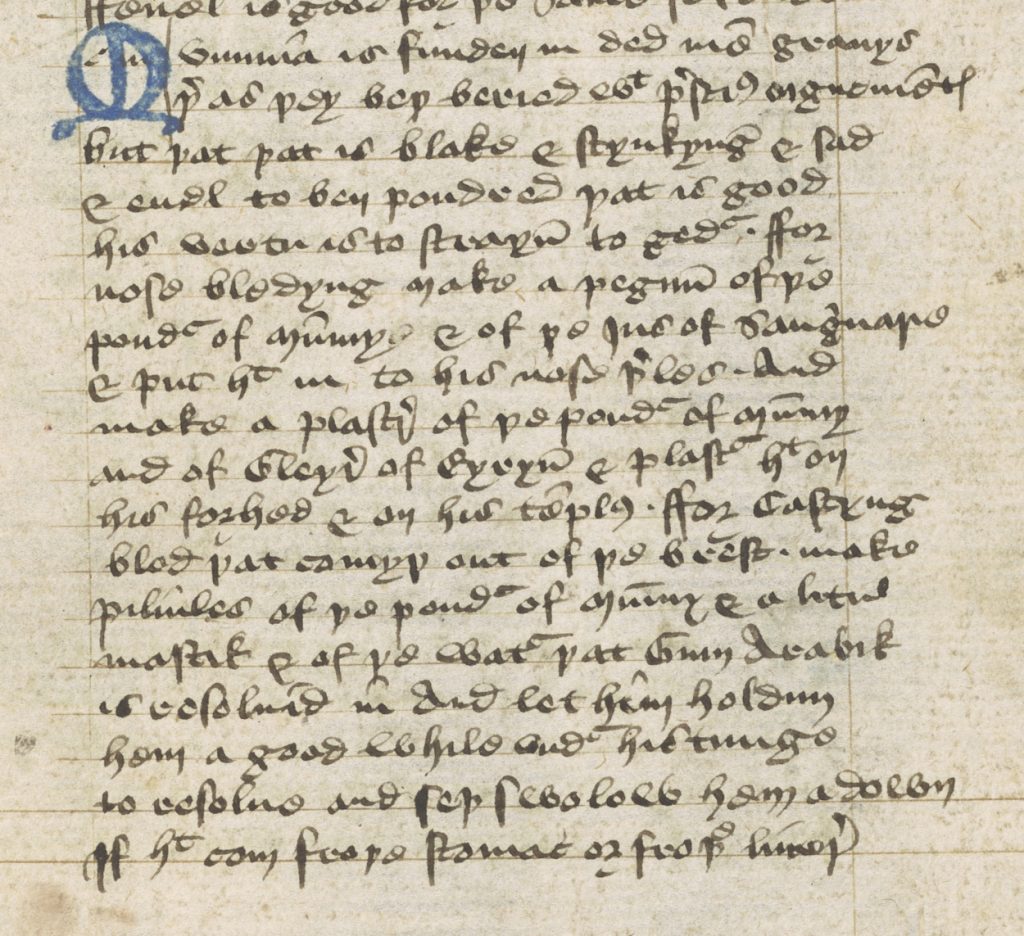

A Middle English translation of the Latin Circa instans – a book on the medical virtues of herbs, minerals, and animal-based substances – that was attributed to Matthaeus Platearius, for example, states that:

Mummia is finden in ded men gravys þer as þey beþ beried with prescious oignementes but þat þat is blake and stynkyng and sad and euel to ben poudred þat is good…

Mumia is found in dead men’s graves, there where they have been buried with precious ointments, but as much as it is dark and stinking and sorrowful and miserable as much is it good when it has been ground up…

The text subsequently recommends working ‘pouder of mummy’ (powder of mummy) into a medicine against nosebleeds that needs to be placed into the nostrils and applied to the forehead and temples. Another medicine to cure patients who cough up blood involves a pill of the same powder which must be held under the tongue for a while before swallowing. As with skull moss, the powder of mummy was believed to contain a deceased individual’s residual life-force that could be harnessed for medicinal purposes.

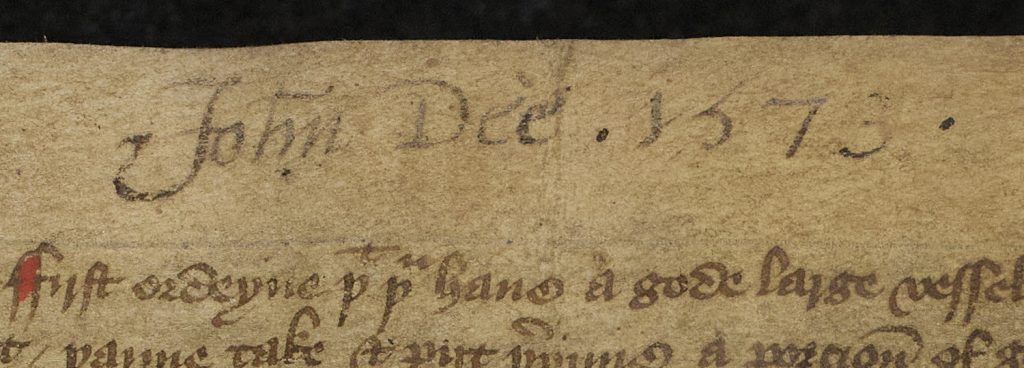

The manuscript in which the weapon salve occurs (Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O.9.39) has been identified as the collection of ‘various chemical experiments’ (‘varia experimenta chimica’) in Dee’s 1583-catalogue of his manuscripts, now Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O.4.20. The catalogue entry could theoretically only describe the manuscript’s first thirty-six parchment leaves which contain a fifteenth-century collection of Middle English recipes for making inks, pigments, and dyes. It is in this portion of leaves that we also find an inscription of Dee’s name together with a date added to an empty margin: ‘John Dee .1573.’

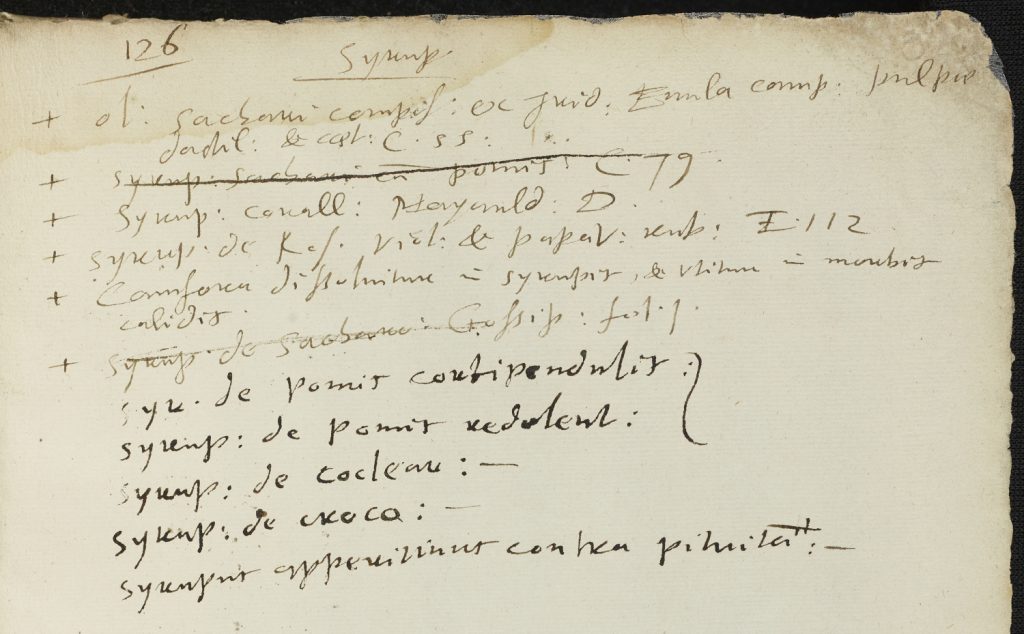

The Trinity College manuscript consists of five different parts that were written at different times and joined together at an unknown point in the early modern period. The recipe in question occurs in the final part, which contains a sixteenth-century collection of medical recipes in Italian with later additions in English. Although this part bears no direct evidence of Dee’s ownership, the manuscript may well have been compiled by Dee: according to Julian Roberts and Andrew G. Watson in John Dee’s Library Catalogue (1990), the manuscript’s fourth part, is filled with medical recipes written in Dee’s hand. This suggests that he may have been responsible for compiling the manuscript’s different parts or, at least, some of them.

Another intriguing piece of evidence is that the same recipe with the exact same title (‘To make a salve that healeth though a man be 30 miles of’) can be found in a manuscript, now Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 1488, compiled by the physician and astrologer Richard Napier (1559–1634). Napier and Dee were well acquainted with one and another. The same Oxford manuscript records that they dined together on 2 July 1604 and that Dee showed him an alchemical manuscript on this occasion. Is it possible Dee and Napier shared the weapon salve too?

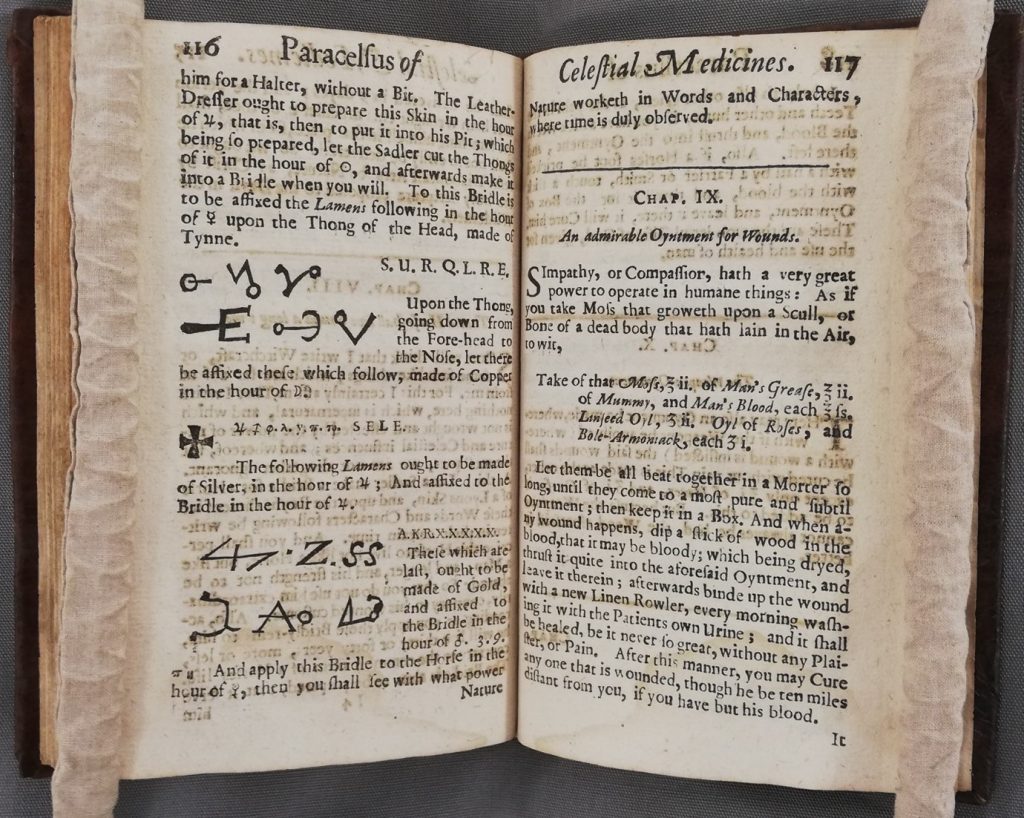

Finally, the recipe also fits well with what is known about Dee’s interest in medicine. Dee was an admirer of the Swiss-German physician, botanist, and alchemist Paracelsus (1493–1591) and owned numerous copies of his printed works. Paracelsus has long been credited as the weapon salve’s creator since it first appeared in the Archidoxis magica, a grimoire that was spuriously attributed to him and published as the final book of his collected works in 1591. Whatever was the case, Paracelsus supported the main concepts underlying the weapon salve: not only did he encourage the pharmacological use of the human corpse but he also promoted ‘sympathetic medicine’. The latter concerns medicine that was believed to cure an ailment through a shared characteristic. The efficacy of weapon salve is an example of this. Namely, the shared feature between the weapon that needs to be anointed and the wound that it has caused is that both contain the patient’s blood. The salve was believed to sympathetically establish a connection between the blood on the weapon and that of the wound, providing a more effective cure than any other medicine that was directly applied to the wound could facilitate.

Although weapon salve would become popular in the seventeenth century, the Trinity College manuscript seems to be a witness to its earliest circulation among English supporters of Paracelsian medicine. More specifically, it may shed new light on Dee’s medical interests. That this recipe should come to light in a manuscript at Trinity College is fitting since Dee was one of the institution’s original Fellows upon its foundation by King Henry VIII in 1546.

You can now enjoy a newly digitised version of Trinity College, MS O.9.39 on the Cambridge Digital Library and the Wren Digital Library. The Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries project is grateful to Anne McLaughlin, Digitisation Services Manager at Trinity College, and photographer Sam Forder-Stent, for providing new photography of the manuscript.

All images reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Further reading:

- Karl H. Dannenfeldt, ‘Egyptian Mumia: The Sixteenth Century Experience and Debate’, The Sixteenth Century Journal, 16:2 (1985), 163-180.

- Michael Camille, ‘The Corpse in the Garden: Mumia in Medieval Herbal Illustrations’, Micrologus, 7 (1999), 296-318.

- Richard Sugg, Mummies, Cannibals, and Vampires: The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians (London: Routledge, 2011).

- Christopher J. Duffin, ‘‘The periwig of a dead cranium’: Medicinal Skull Moss’, Pharmaceutical Historian, 52:3 (2022), 75-85.

I’m looking forward to visiting the library and exhibition this weekend. I’ve been interested in the potential efficacy of “old cures” for some time and my personal research concerns the potential antimicrobial activity of common churchyard lichens. I’m not surprised that “moss” and “lichen” could be mixed up historically before we got around to botanical taxonomy.

Usnea

I was trying to write about the possible confusion between Usnea lichens and mosses, then I submitted by mistake (sorry). Usnic acid is one of the most reported antimicrobial agents from lichens. https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/fungi-and-lichens/beard-lichens/