Finding Henry Morris in the Cambridge University Press archives

This post is by Anna Crutchley, an archivist and textile designer-maker who teaches workshops in adult education centres around the country, including weaving at Cottenham Village College Summer School.

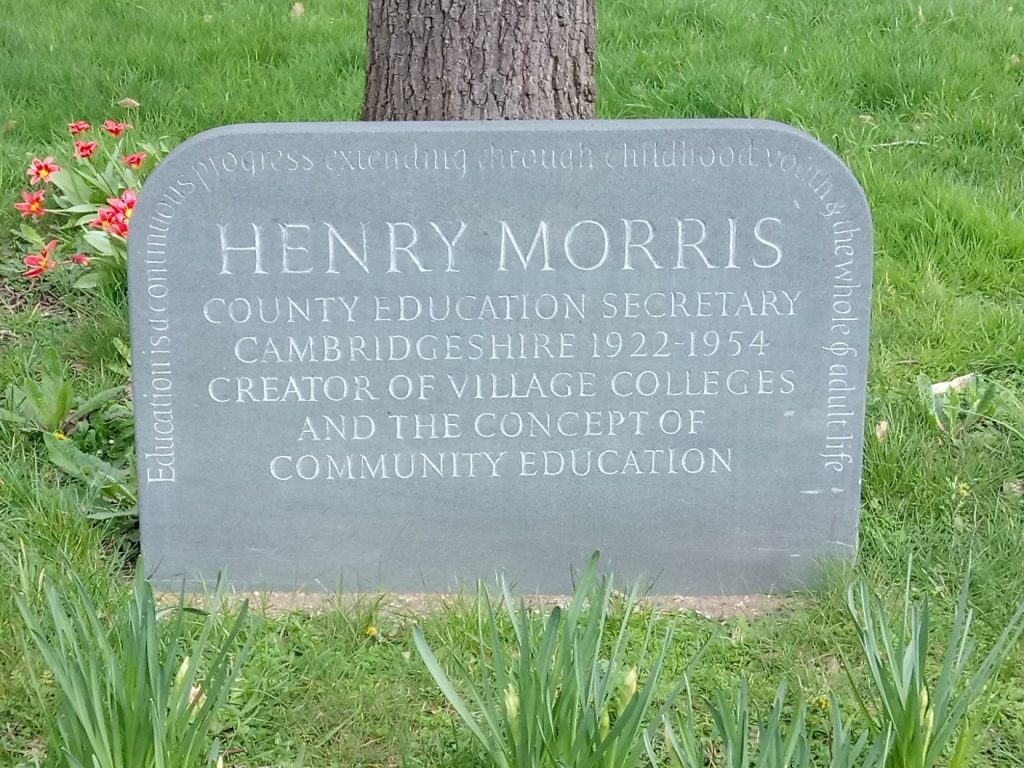

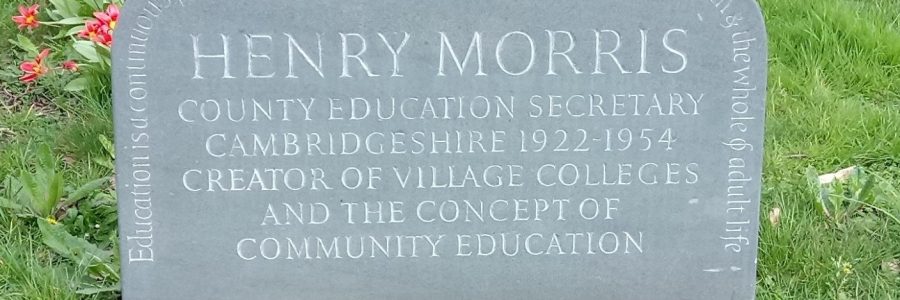

Henry Morris (1889-1961) was Cambridgeshire County Council Secretary for Education from 1922 and Chief Education Officer from 1944 until 1954. This year marks the centenary of his treatise on community education, in The Village College: being a memorandum on provision of educational and social facilities for the countryside, with special reference to Cambridgeshire.[1] Many people in Cambridgeshire have heard of Morris, and many others haven’t. For those who do not know about him, this story of his trials and eventual victory in fundamentally changing the nature of education in the countryside will inspire you. His story is told in part through materials in the archives of Cambridge University Press, held at the University Library.

Morris was the seventh of eight children brought up in Lancashire, the son of a plumber, and left school at the age of fourteen. In his late teens he decided to join the church and become a vicar, however, after joining up for military service in 1914, decided not to follow that vocation. He had lost his faith due to the war, although continued throughout his life to love the traditions of the church and was instrumental in developing systems for the teaching of Religious Education. He went on to attend Exeter College, Oxford and came up to King’s College Cambridge where he read Moral Sciences (Philosophy). He took a position as Assistant Education Secretary in Cambridge in 1922, advancing to Chief Education Officer from 1944 to 1954.

He was a singular and determined man, and saw that schooling in the countryside outside of towns was poor, and scandalously so in Cambridgeshire where Cambridge University boasted a quality of education of world renown, but local village education was severely underfunded and outdated. Before his arrival, education in some villages often existed in single school buildings, where children of all ages might be taught in one room, and by one teacher. Unless schoolchildren were able to attend one of the Cambridge schools, their education was limited and usually cut short. Even if they did come in to a Cambridge school, it did not set them up adequately for returning to village life and making appropriate contributions to their communities. Morris wrote,

Owing to the operation of the free-place scholarship system, the abler children are taken away from the country schools, where they receive a predominantly literary and academic education under urban conditions divorced from the life and habits of the countryside. [2]

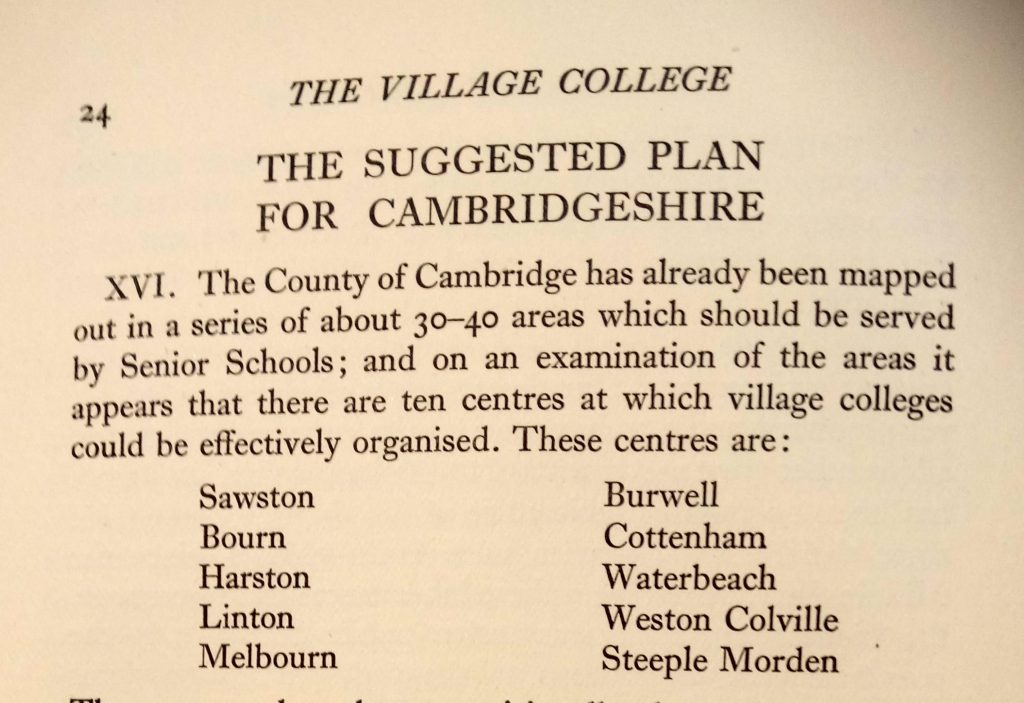

He determined that ten village colleges should be built, ‘to provide for the co-ordination and development of all forms of education – primary, secondary, further and adult education, including agricultural education – together with social and recreational facilities.’ [3]

To achieve funding for his vision for community colleges he decided to visit the USA in 1929. He financed his own trip and was successful in gaining generous donations from the Spellman Fund and Carnegie Trust. In the UK, Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst, Americans who had established the progressive Dartington School and College of the Arts in Devon in the mid-1920s, donated towards the building of Sawston Village College. Landowners, such as Spicers in Sawston and Chivers in Histon gifted land for the new schools. Meanwhile, Cambridgeshire County Councillors who never believed in his ideas, allotted him £5 for his trip, and consistently resisted adequate funding for the schools. To Morris, a village college should be,

A building that will give the countryside a centre of reference arousing the affection and loyalty of the country child and country people, and conferring significance on their way of life. [4]

He believed that good design was central to enhancing engagement and pride in education, and in his extensive section on school architecture in the ‘Memorandum’, espoused the Bauhaus ideals of humanism and social connectivity. He met Bauhaus director, Walter Gropius, who had fled the encroaching Nazi regime in Germany in 1937 to settle in London, setting up an architectural practice with Maxwell Fry, and commissioned them to design Impington Village College. Later on, Gropius’ Bauhaus colleague, Lázló Moholy-Nagy, who had also left Germany for England in 1935, provided original artwork and colour schemes for Linton Village College.

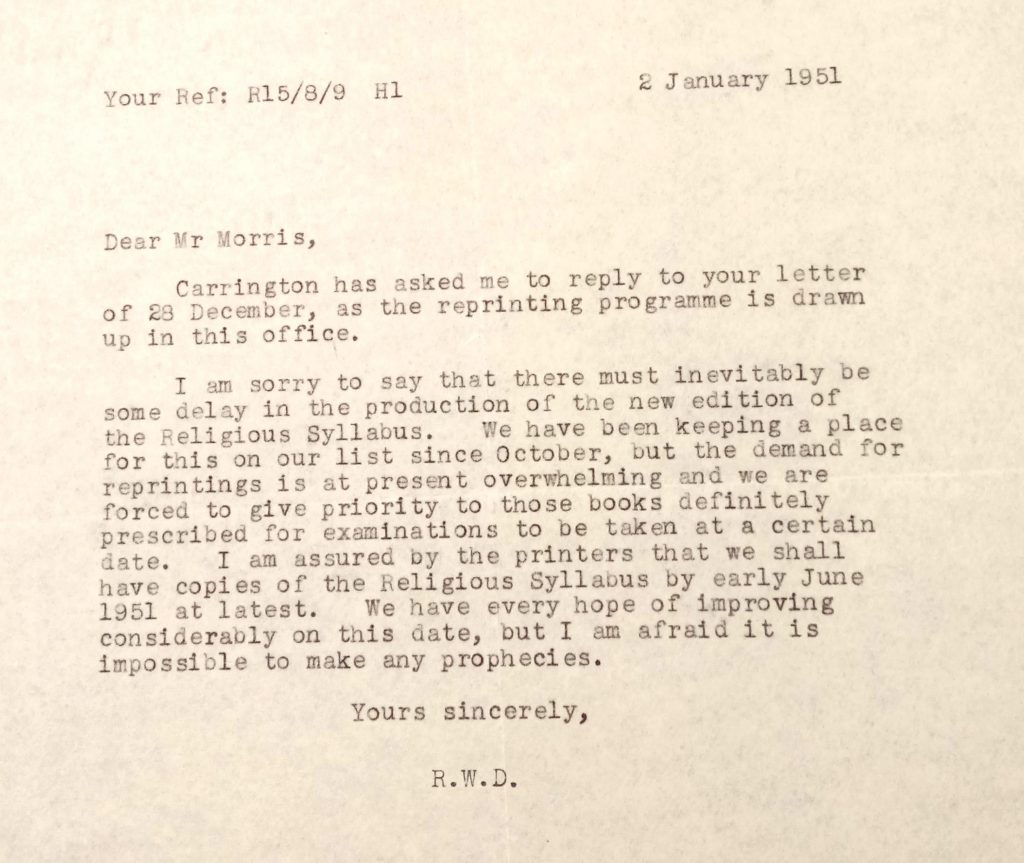

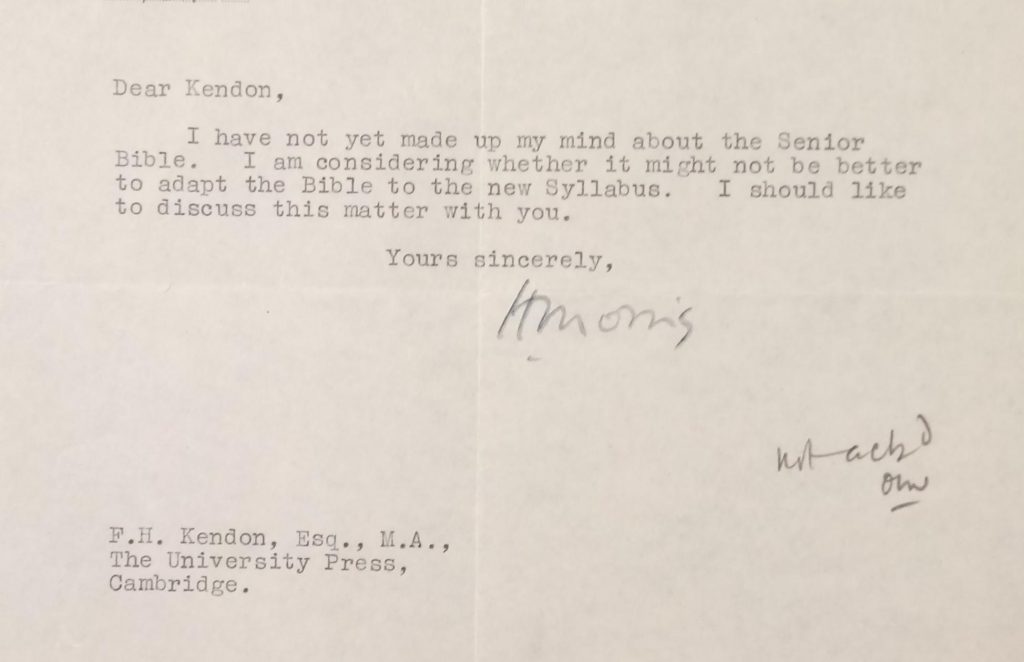

I had heard of Morris, but my interest in his inimitable, and irascible, character was sparked by a correspondence in the Cambridge University Press archives, specifically the author files of 1948 to 1951, concerning delays in the production of the Cambridge Senior Bible and accompanying school syllabus.[5] The two letters below show a gap of well over 2 years before the Religious Education and Cambridge Senior Bible were published. Richard David’s letter explains the delays in the Press printing schedule, as was the norm for several years after the end of the war. In spite of this, delays were mainly due to Morris’ unexplained hesitations rather than the printing schedule.

Correspondence between CUP publishers and authors was always cordial and prompt, but the responses from Morris were strangely difficult, and his delays in presenting material to be printed unexplained. A letter from the publishers to the renowned theologian, Professor C.H. Dodd tells,

I had a long conversation this morning with Henry Morris who was entirely friendly, but as always, a little difficult to deal with. [6]

Morris was known for being tetchy and eccentric, and likely to blow his top with his superiors and staff, but he had many friends who loved him dearly and appreciated his energy and commitment. He used to invite them to supper in his flat in Trinity Street, and many went on to positions in other county and city councils taking their experience of working with him, and establishing village or community colleges elsewhere, notably in Leicestershire, Hertfordshire, Nottingham and Coventry.

Sawston was the first village college to be founded, with the Prince of Wales planting a tree on 30th October 1930. Students and staff at Sawston celebrated its 80th anniversary by producing a video in which they re-enacted the story creating an imaginary young trainee teacher, who in the early 1960s, being so inspired when she heard about Morris’ legacy, set out to meet up with his old colleagues and ever faithful secretary.[7] This narration of her story was aided in the video by the then County Chief Education Officer, Geoffrey Morris (no relation), David Farnell of the Henry Morris Memorial Trust and Bryan Howe of the Sawston Village History Society.

Morris’ influence was widespread, and eventually stretched across the country via officers who had worked with him at Cambridgeshire County Council before moving on. Although his vision was to create 10 village colleges outside Cambridge, not all were built in his lifetime. His successor, George Edwards, continued to ensure that more were built, providing adult education and other social facilities to their communities. To Morris, the village college was meant,

to take all the various vital but isolated activities in village life – the School, the Village Hall and Reading Room, the Evening Classes, the Agricultural Education Classes, the Women’s Institute, the British Legion, Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, the recreational ground, the branch of the County Rural Library, the Athletic and Recreational Clubs, the work of village local government – and bringing them together into relation, create a new institution for the English countryside. [8]

The two books listed below on Morris talk a great deal about the flaws in his character – his frequent and scathing tirades on colleagues and superiors, as well as his triumphs. He was greatly appreciated by Rab Butler, President of the Board of Education 1941-1945, and creator of the Education Act of 1944. Morris’ eccentricity, however, was not tolerated by Whitehall civil servants and resulted in his inability to convince government to adopt his ideas about village colleges nationally.

Now, in 2024, as we continue to face deficits in expenditure on our schools and social facilities, we should never forget Morris’ legacy. Many of us have so greatly benefitted from it.

Sources

Cambridge University Library, University Archives, Press 3/1/4/2379. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

‘Henry Morris; the Life and Legacy‘ is a video available on the Sawston Village College website (2020). It is also available as part of the records of the Henry Morris Trust. Reference: R120/038/10 at Cambridgeshire Archives.

Henry Morris Memorial Trust https://henrymorris.org/about-henry-morris/

Morris, H., ‘The Village College: being a memorandum on provision of educational and social facilities for the countryside, with special reference to Cambridgeshire‘ (Cambridge University Press, 1924). Also available at Cambridgeshire Archives.

Rée, H., ‘Educator Extraordinary, The Life and Achievement of Henry Morris 1889-1961’, (Longman 1973).

Rooney, D., ‘Henry Morris, The Cambridgeshire Village Colleges and Community Education’, (Henry Morris Memorial Trust, Sawston Village College, 2013).

Sawston History Society http://www.sawstonhistory.org.uk/svc.htm

Sawston Village College https://sawstonvc.org/about-us/history/

Acknowledgements

Dr Rosalind Grooms, Archivist, Cambridge University Press

Lesley Morgan and Peter Hains of the Henry Morris Memorial Trust

Sawston Village College for the portrait of Morris

[1] Morris, H., ‘The Village College: being a memorandum on provision of educational and social facilities for the countryside, with special reference to Cambridgeshire’ (CUP 1924), known as the ‘Memorandum’.

[2] Ibid, p.1.

[3] Ibid, p.1.

[4] Ibid, p.20.

[5] Cambridge University Library, University Archives, Press 3/1/4/2379

[6] Ibid

[7] ‘Henry Morris; his Life and Legacy’ video (2010), Sawston Village College website, accessed August 2024

[8] Morris, H., ‘Memorandum’