‘Our singular patron’: Thomas Cromwell and Cambridge University

TV viewers enjoying the tumultuous final episodes of Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light may be interested in Thomas Cromwell’s impact on Cambridge in the 1530s.

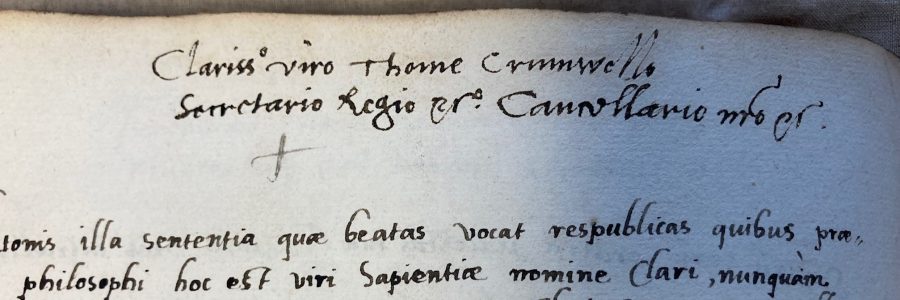

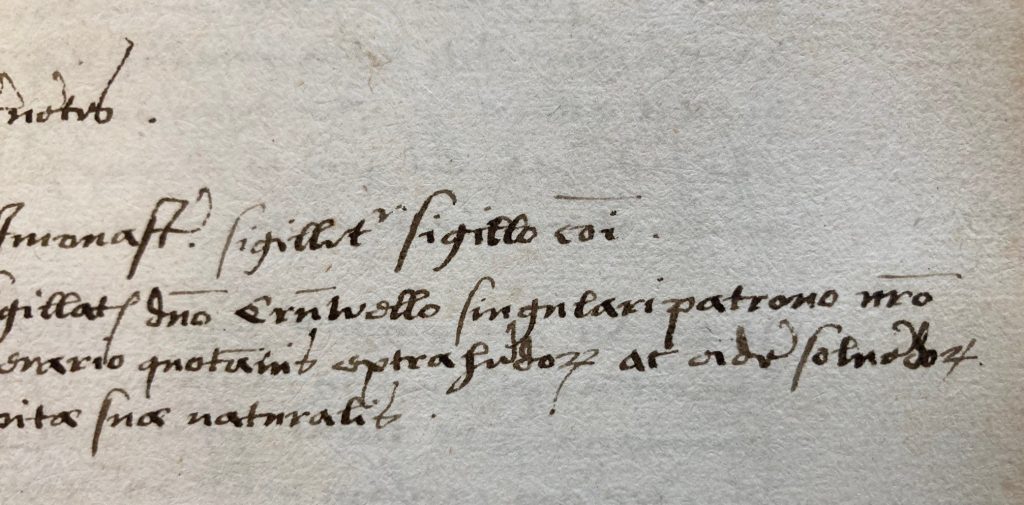

The University first recognised the need to honour his growing power in 1533 by granting him, ‘our singular patron’, an annuity of £2. It did better the following year, appointing him High Steward in succession to Lord Mountjoy, until recently veteran Chamberlain to Queen Katherine, and symbol of a previous age.

The ultimate accolade came in 1535. Cambridge colossus John Fisher had been Chancellor of the University since 1504. His long University career included the Lady Margaret Professorship of Divinity, senior proctorship, vice-chancellorship, headship of both Michaelhouse and Queens’ College and primary role in the foundation of St John’s College. He was executed in June 1535 after refusing to take the oath recognising Henry VIII as supreme head of the English church and the new laws of succession. Elected his successor, Cromwell was no University man, closely involved in Fisher’s execution and, since January 1535, the King’s vice-regent in matters spiritual.

Cromwell has been described as ‘As lay a person and devoid of spiritual aura as could be found in England’ (1). But whatever his demeanour and focus on overhauling government, recent research (2) also emphasises his evangelical beliefs from the early 1530s onwards. A commitment to reformed religion as embodied in teaching and learning is evident among his innovations at Cambridge.

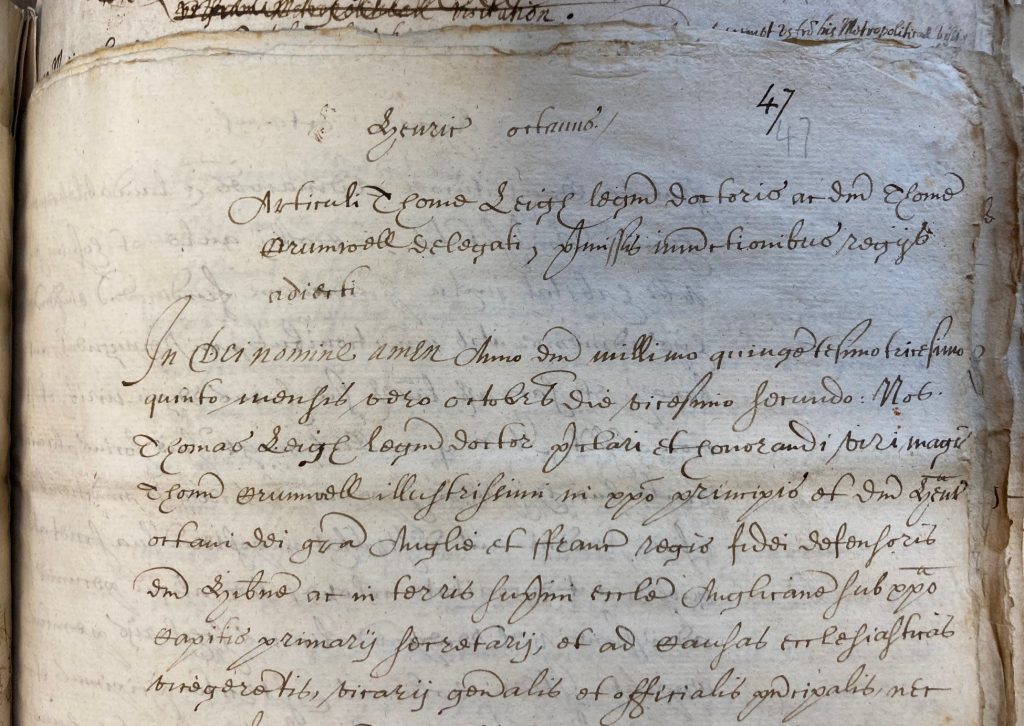

His five year tenure marked the first time secular government intruded into the internal affairs of the University; controlling its administration, curriculum and internal custom. Royal injunctions to the University were issued in autumn 1535 and a visitation ordered (3). Cromwell did not exercise the power of visitation personally but appointed Dr Thomas Leigh (d.1545), Doctor of Civil Law, of King’s College, already proven a loyal servant as diplomat and would-be suppressor of monasteries.

Alongside the foremost requirement that University members swear of an oath of allegiance to the Church of England and Royal Supremacy, the injunctions prohibited the use of the great medieval textbooks of Theology and biblical commentary (such as Peter Lombard’s Sentences and others, full of ‘frivolous questions and obscure glosses’) and demanded instead that Theology lectures be centred on the Bible. They encouraged direct engagement with the biblical text: students were to be allowed to read the Bible privately. The study of Canon Law and degrees in it were to be abolished. Colleges and the University were all to establish public lectures in Greek and Latin; the University was additionally to maintain one in Hebrew.

College fellowships were not to be sold but awarded instead on merit. Geographical and collegiate factionalism was to end. University, College and hostel officers were to surrender their ‘papistical muniments’ and provide an inventory of their rental and moveable property to Cromwell for review. Finally, all should attend a commemorative mass in the University Church, Great St Mary’s, for College and University benefactors and for the King and Queen.

Most radical of curriculum reforms was the abolition of Canon Law. The basis of organisation in the Western Church for four centuries, its student numbers in the Middle Ages had rivalled those in the arts faculty. But if the King was now final arbiter in all matters of law, no appeal to the outside authority of the Pope would be tolerated.

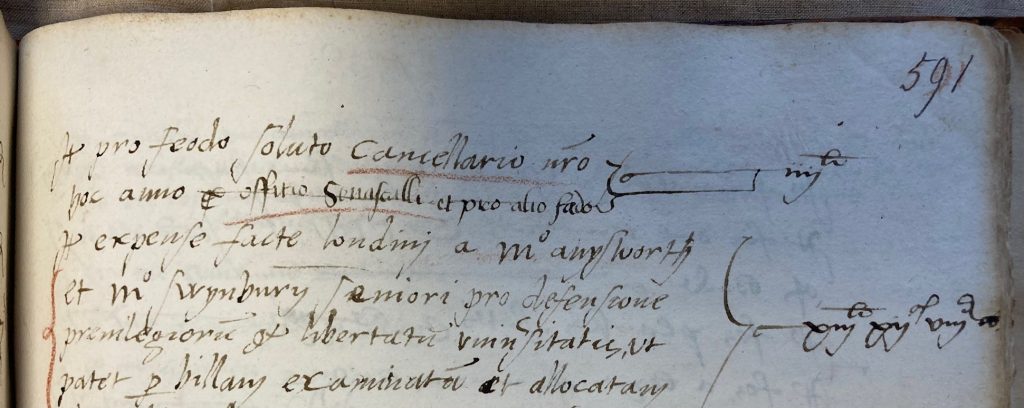

The University’s first priority was to get its charters, rights and privileges reconfirmed in the King’s name and send in an exact rental of lands and inventory of their goods. The Vice-Chancellor was in London for 38 days at considerable expense to achieve this. The oath of allegiance was implemented and in modified form was required of the University until 1871.

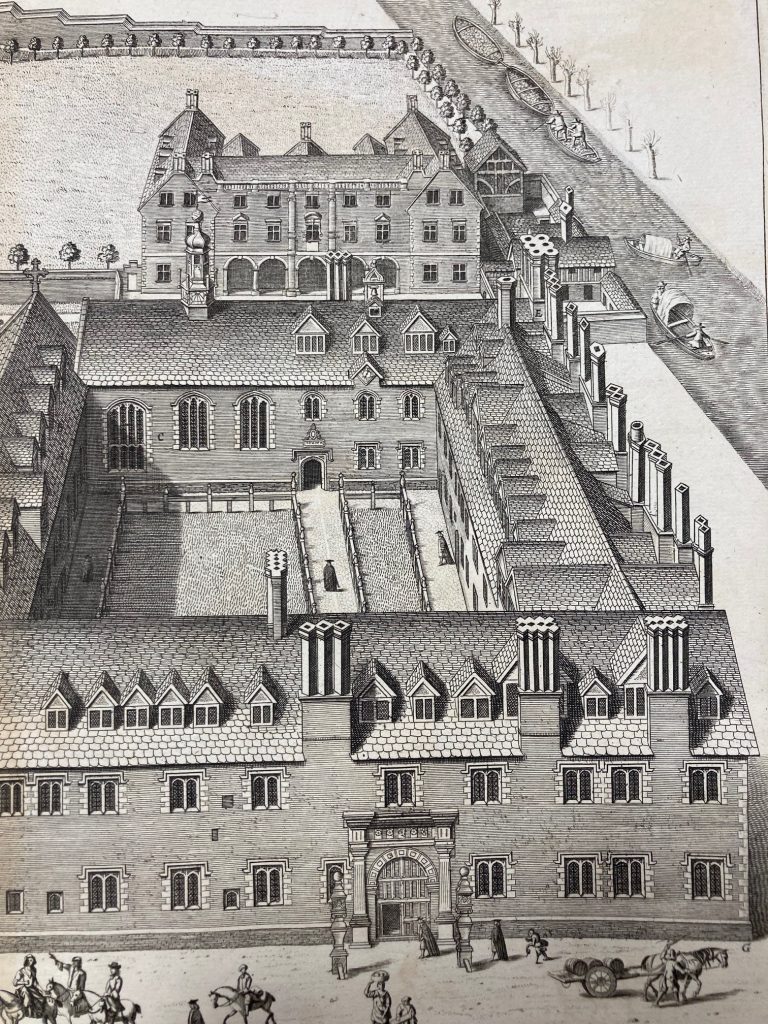

The dissolution of the monasteries across the country from 1536 onwards signalled Cromwell’s intentions regarding the Orders of Friars studying in Cambridge and living together in communities apart from the Colleges. By the time the axe fell in 1538, the Friars were down to twenty-four Franciscans and sixteen Dominicans had already started to sell and/or dismantle their convents. The Junior Proctor’s accounts for 1536-7 show the Austin and Blackfriars selling and ‘lending’ their lead roofs for repairing the libraries in the Schools buildings (4). Spared dissolution themselves, among several acquisitive Colleges, Queens’ made purchases of walls, tiles, and rubble from their neighbouring Carmelites. In 1542, Thomas, Lord Audley (1487/8–1544) re-founded Buckingham College, formerly the home of the Benedictines, as the College of St Mary Magdalene, now more familiarly Magdalene College.

We know Cromwell met the same end as Fisher – executed in 1540 – accused of heresy and treason, his reputation trashed by brokering the disastrous Cleves marriage, his aristocratic enemies circling, lead by the Duke of Norfolk. He was succeeded as Chancellor by one of the possible architects of his downfall, Stephen Gardiner (c. 1495×8–1555), Bishop of Winchester, and former master of Trinity Hall.

References

- G.R. Elton Reform and Reformation: England 1509-1558 (1977) p.191.

- Damian Leader A history of the University of Cambridge. Volume 1, the University to 1546 (1988); E.S. Leedham-Green A concise history of the University of Cambridge (1996); Diarmaid MacCullough Thomas Cromwell: a life (2018)

- Registry guardbook of miscellaneous documents, classmark: UA CUR 78.47

- UA Grace Book Beta pp.575-6

Thank you so much for a clear, informative and beautifully illustrated piece which has prompted my curiosity while extending my knowledge.