Ladies in the Library

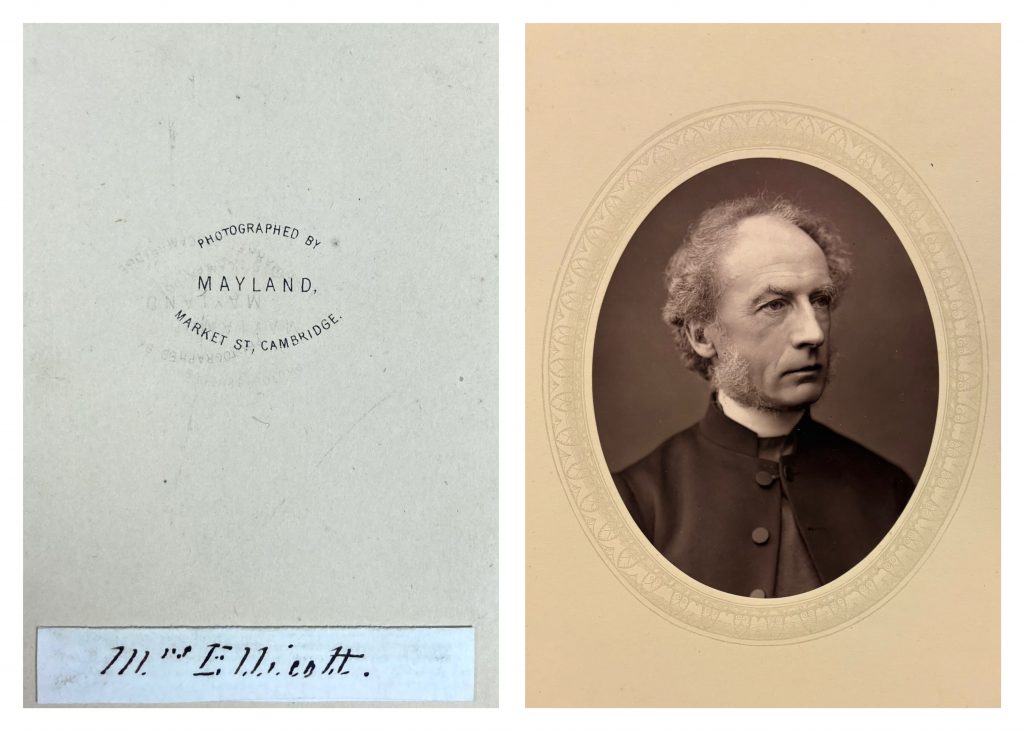

January 1855. The British coalition government was in crisis over accusations of mismanagement in the Crimean war. In the literary world, the final installment of Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South was published in Charles Dickens’s periodical Household Words. Two months later, Gaskell’s friend and fellow novelist Charlotte Brontë died, two years after the publication of what would be her last work, Villette. Meanwhile, at Cambridge – 170 years ago today – a different kind of history was being made when the first women were granted admission to the University Library as readers in their own right. A recent acquisition by the University Library of a tiny carte de visite photograph gives us a glimpse of one of those women.

Constantia Ann Ellicott was one of three women and three men given access to the UL under new rules that allowed members of the public to apply for reader’s cards. [1] The two other women were a Mrs Barrett and Mrs Jessop. The change came about partly in response to the Royal Commission that had been appointed to report on the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, and which had noted in 1852 the desirability of admitting ‘strangers’ to the Library. This would be ‘in accordance with the liberal principle, which has been so generally acted upon by the University of late years, of throwing open their collections of every kind as widely as was deemed consistent with their safety and with the special objects which they were required to answer.’ [2] Although people from outside the University had been able to enter the Library before this date – either as guests of University members, or by permission of the Vice Chancellor – this was the first time they had been able to apply for their own reader’s cards.

Mrs Ellicott was the wife of the theologian Charles Ellicott (1819–1905), who had given up his fellowship at St John’s College, Cambridge in 1848 to marry her. He worked at the parish of Pilton in Rutland from 1848 to 1858, afterwards going to King’s College London as Professor of New Testament. In 1859, he gave the Hulsean Lecture on Christian theology at Cambridge and was elected to the Hulsean professorship the following year, holding the position until 1861, when he was appointed Dean of Exeter. In 1863 he was appointed Bishop of Gloucester and Bristol.

The photograph of Mrs Ellicott shows her in full crinoline in a classic carte de visite pose in the studio of William Mayland (the chair features in other photographs by him), taken side-on to show off the dress and with a hand on the back of the chair as an aid for standing still. Mayland had set up in Market Street in Cambridge in 1858 and was one of the earliest commercial photographers in the city. By the end of 1864, he had moved to premises in St Andrew’s Street, which means that the portrait of Mrs Ellicott was taken sometime between those dates and presumably before the Ellicotts left Cambridge for Exeter in 1861. [3] So, in 1855 when Mrs Ellicott was given her reader’s card, she was living in Rutland, with her husband and two young children – five-year old Arthur, and Florence, aged three or four. Her second daughter, Rosalind, was born in Cambridge in 1857 and became a noted composer. [4]

Mrs Ellicott was herself an accomplished singer. In 1860, the University Registrary Joseph Romilly remarked in his diary that ‘Mrs Ellicott stunned me with her singing’. [5] She performed many of her daughter Rosalind’s songs and was a moving force ‘in the founding of such illustrious groups as the Handel Society and the Gloucester Choral Society’. [6] Alongside music, and helped by her daughters, Mrs Ellicott also ‘formed at Gloucester a working girls’ club, which is regarded as the model of what such an institution should be, and she has taken a great interest in Church Sunday school teachers of both sexes. While she was still a young married woman, Mrs. Ellicott started the Queen’s Square Hospital for children suffering from hip-disease, and she has for many years been a strong supporter of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.’ [7]

By 1871, sixteen years after Mrs Ellicott was admitted to the Library, both Girton and Newnham had been established and the Library granted the first reader’s card to a woman student, Ella Bulley of Newnham. Between 1855 and 1871, some thirty-five women had joined the Library and almost two-thirds of them had renewed their tickets at least once (though sadly not Mrs Ellicott, Mrs Barrett nor Mrs Jessop), evidence that the Library of the mid-nineteenth century was home to a small group of regular women readers. Importantly, however, the card granted to Bulley was done so on the same basis that one had been granted to Mrs Ellicott – as a member of the public, since women were not considered members of the University. It would be fifty more years – 1921 – before women students were given the same library privileges as their male counterparts, and it was not until 1947 that they would be awarded degrees and granted full membership of the University.

By 1871, when Ella Bulley got her reader’s card, Mrs Ellicott was long established in Gloucester with her husband. In July that year she had sung in the chorus for the first complete British performance of Brahms Requiem, which took place in the home of the pianist Kate Loder. [6] Like the Ellicotts, the literary world had also moved on. Dickens had died the previous year and Mrs Gaskell in 1865; the first part of George Eliot’s Middlemarch was published by William Blackwood and Sons in December 1871 and Henry James’s short novel Watch and Ward launched as a serial in The Atlantic Monthly. Replies to letters from Mrs Ellicott from both Dickens and James survive – the first to a social invitation, politely declined.

Mrs Ellicott blazed a trail for women in the Library ahead of the arrival of the women’s colleges and women with little or no connection with the University continued to be admitted as readers – as did men. Women and men alike were given access as ‘persons who are not members of the University wishing to consult the Library for the purpose of study or research’. [8] Mrs Ellicott’s history, then, is of twofold importance – as a lady in the mid-Victorian University Library, but also as part of Cambridge University Library’s long and proud tradition of welcoming a large and active community of readers through its doors.

Notes

[1] See also Jill Whitelock, ‘“Lock up your libraries”? Women readers at Cambridge University Library, 1855–1923’, Library & Information History 38.1 (2022): 1–22.

[2] Report of Her Majesty’s Commissioners Appointed to Inquire into the State, Discipline, Studies, and Revenues of the University and Colleges of Cambridge (London, 1852), p. 132.

[3] Fading Images, ‘Cambridge photographers’, https://www.fadingimages.uk/photoMas.asp.

[4] Salon Without Boundaries, ‘Rosalind Ellicott 1857-1924’, http://www.salonwithoutboundaries.com/composer-of-the-month-1/2022/6/14/rosalind-ellicott-1857-1924.

[5] Romilly’s Cambridge diary 1848–1864: selected passages …, ed. by M. E. Bury and J. D. Pickles (Cambridge, 2000), p. 370.

[6] Frederic Sawrey Archibald Lowndes, Bishops of the day (London, 1897), p. 111.

[7] Salon Without Boundaries, ‘Kate Loder and the Brahms Requiem’, http://www.salonwithoutboundaries.com/the-salon-blog/2022/7/11/kate-loder-and-the-brahms-requiem.

[8] Cambridge University Library, UA/ULIB 1/2/2, pp. 45–48.