Francis Fry: Maker of Chocolate … and Catalogues

This post is by Dr Harry Spillane, Munby Fellow in Bibliography for 2024/25. His research project, entitled ‘Collecting and Correcting: Histories of the English Bible and the Bible Society Collections’, explores how Bibles were collected, edited and reshaped in the centuries after they were printed.

Francis Fry (1803-1886) combined two of life’s great pleasures: chocolate and bibliography. Francis was an heir to the chocolate company J.S. Fry & Sons, founded in Bristol in 1761. Fry’s grew into a hugely successful business, having created the first solid and first filled chocolate bars. With the considerable wealth he amassed, Francis Fry was able to assemble one of the largest, if not the largest, private collections of bibles. Whilst the Fry collection included many thousands of bibles from across the globe, Fry’s collection of over 1,200 English bibles constituted the most complete and significant window into the history of the English bible ever gathered together. Following Fry’s death, this part of the collection was purchased by the British and Foreign Bible Society, and now resides in the University Library at Cambridge. All of the catalogues by Fry and the Bible Society referenced here are now catalogued as BSA E3/6/2/3 [1].

Whilst Fry’s habits of collecting constitute the broader project I am pursuing as a Munby Fellow, the subject of this post is the catalogues that were created for this unique collection by Fry and the Bible Society. This is because these catalogues open up significant questions about the purpose of the collection and how the history of the English Bible has been shaped by decisions made by generations of cataloguers. This raises questions which go well beyond the history of the Bible, causing us to consider how catalogues functioned in a pre-digital age to aid usability, but also how catalogues might have cemented errors and misconceptions about the texts being described and listed.

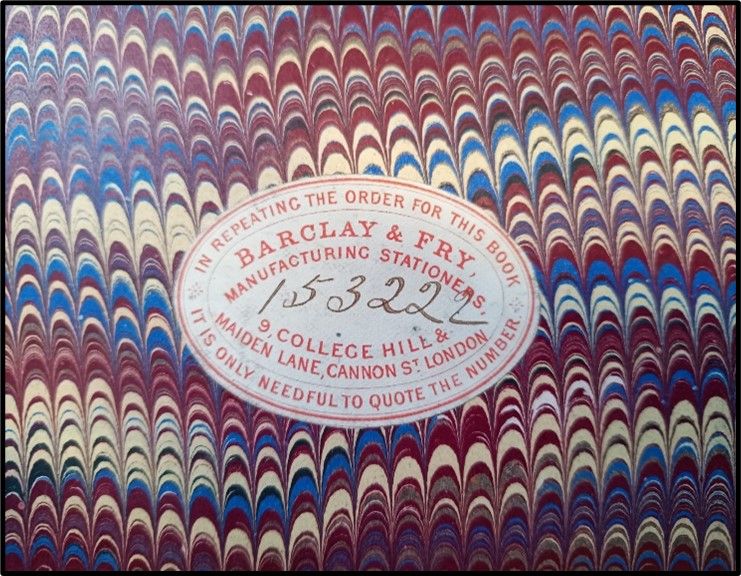

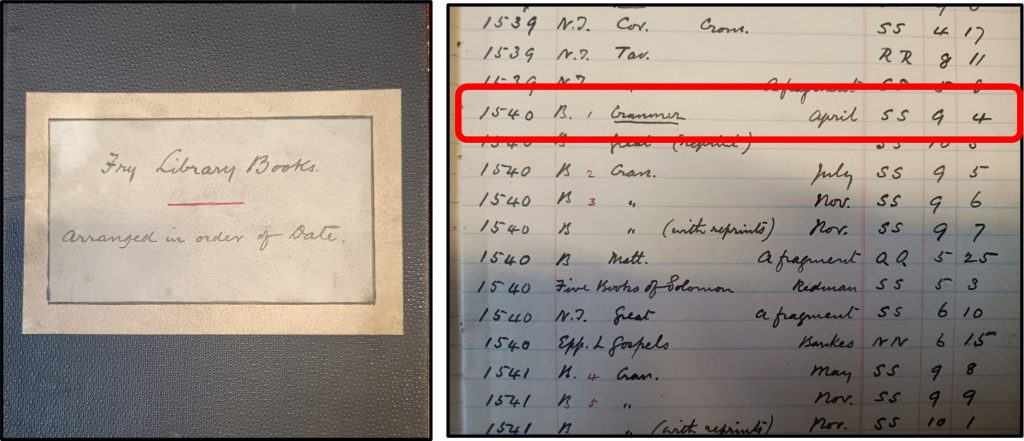

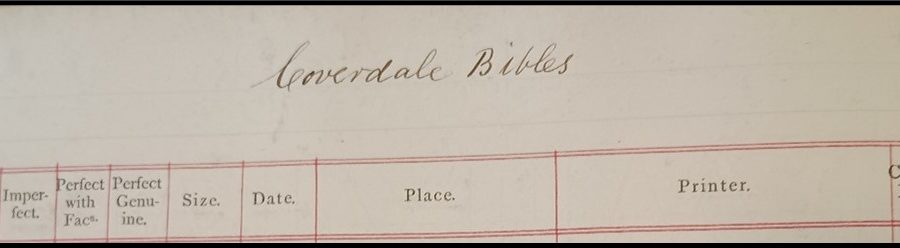

With a house full of bibles, Fry decided in the 1870s that he would produce a catalogue of copies he owned. Fry commissioned a personalized catalogue book which had printed columns for details such as size, date, place and printer, as well as the specific columns which allowed him to note whether copies of the Book of Common Prayer or Metrical Psalms had been bound within his copies. A separate set of columns allowed Fry to record whether he had added facsimile pages to copies or whether he deemed them ‘perfect genuine’. Precisely how Fry decided what was and was not ‘perfect genuine’, and then how he went about fixing these perceived omissions, is the subject of my ongoing Munby Fellowship. Fry did not have to search hard for a stationer to commission his catalogue from, seeing as his son John had founded a stationery business with Robert Barclay in 1855. They produced this catalogue as well as a series of other texts and facsimile printed pages for Fry’s bibles.

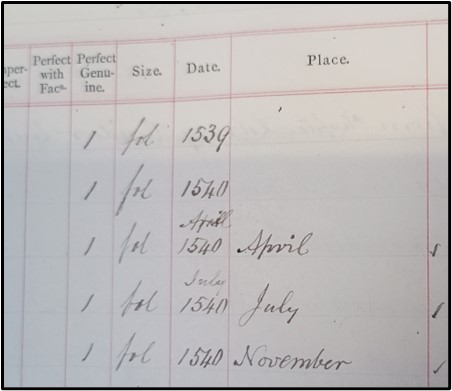

One of Francis Fry’s particular interests was in the history of the first authorized English bible, so called the Great Bible. Let us trace his copy of one of these Great Bibles through the various catalogues produced. We begin with Fry’s own catalogue, where Fry has inserted a record that he owns a ‘perfect genuine’ copy of the April 1540 edition of the Great Bible. So far, so straightforward.

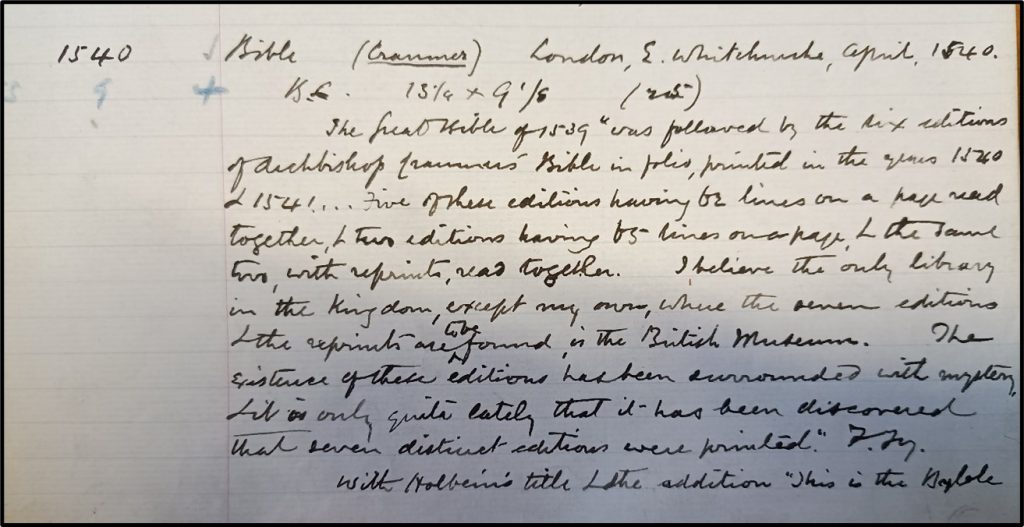

Once Fry’s collection was in the hands of the British and Foreign Bible Society, decisions had to be made about how to store and catalogue it. Fry’s idiosyncratic approach was best suited to his own bibliographical interests, but the British and Foreign Bible Society – an organisation who tasked themselves with translating the Bible into many languages – had different priorities. The collection had moved from a private antiquarian library to a working scholarly library. So William Wright, editorial superintendent at the Bible Society, began work on a new series of catalogues. The first of these is a roughly worked list of descriptions written on basic lined paper. It was not a durable catalogue for frequent use, but it contained information from Fry’s catalogue and the various books Fry had written on the history of the English Bible. We can see the entry for the April 1540 Great Bible being made by Wright here:

Having created this rough work, Wright produced two further volumes which were bound up and designed for regular use within the Society Library. These took all of the basic information about the Fry Collection and arranged this in two different formats. The first of these twin catalogues arranged the Bibles in chronological order and gave to each copy a new reference number. In the case of the April 1540 Great Bible that was ‘SS.9.4’. We can see above how Wright has then added that reference back into the rough draft in blue text.

The second of these twin catalogues arranged the Bibles thematically. For instance, it catalogued which copies were duplicates and it differentiated bibles by language and format. These catalogues were designed to aid those who were using the Bible Society Library as a working collection, so we see how Fry’s information was rearranged and supplemented to meet a new purpose. Wright’s three catalogues offer multiple ways of approaching the same collection depending on the information you have or are looking for. They reveal how institutions created searchable apparatus which could help users navigate collections in the pre-digital catalogue world which we can find it hard to imagine.

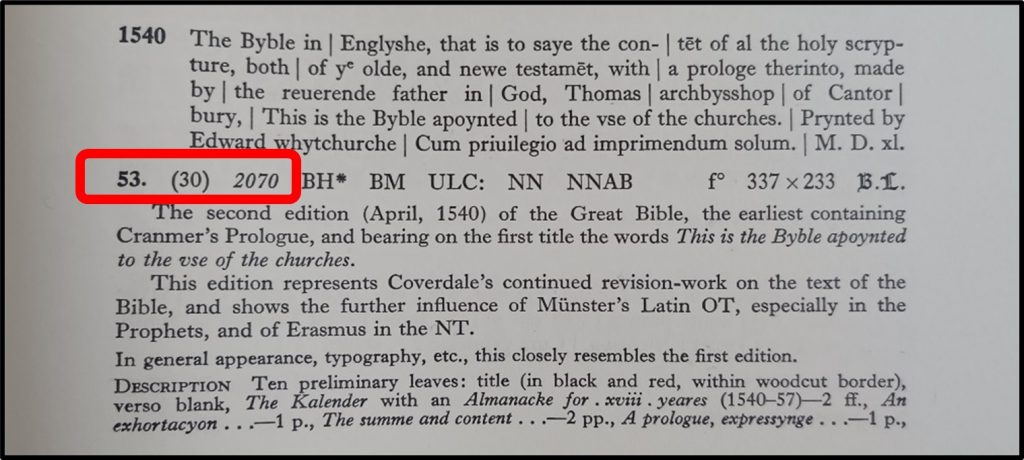

The story does not end with Wright. Two more catalogues were subsequently commissioned, in recognition of the fact that scholarship had moved on and uncovered more about the print history of the English Bible than Fry and Wright had known. T.H. Darlow and H.F. Moule set about producing a new catalogue of English bibles in the Society Library in honour of the 100th anniversary of the Bible Society [2]. Darlow and Moule’s 1903 catalogue arranged the collection chronologically and added to each edition a new number, such that the first English New Testament produced by Tyndale in 1525 became ‘1’. These were distinct from the numbers which Fry had assigned to certain editions within his original collection, and this has continued to cause confusion up to the present day.

Then, in 1967, a revision of Darlow and Moule was made by A.S. Herbert [3]. New discoveries of previously unknown editions and a different system of cataloguing led to the numbers again changing. The April 1540 Great Bible thus moved from number ‘30’ to ‘53’. Today a whole different system of references allows us to search the Society Collection and what has been ‘SS.9.4’, ‘D&M 30’ and ‘Herbert 53’ is today ‘BSS.201.B40.3’. On top of that, amongst many other catalogues which have been produced, the April 1540 Great Bible can also be traced in the Short Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England Scotland and Ireland as ‘STC 2070’ [4].

What now comes to us in an instant on iDiscover is the product of these generations of catalogues, each of which had specific purposes in mind. These questions and catalogue lineages are not unique to bible history, but the enormous quantity of bible editions which have been printed throughout history makes bible bibliography especially complex and messy. These catalogues preserve and chart the history of English bibles, how they have grown, shed errors and misconceptions, but also sustained many. Chocolate might be the more delicious of Fry’s legacies, but his initial catalogue is a fascinating insight into early attempts to riddle out the history of English bible printing.

Notes:

[1] Papers relating to Francis Fry, British and Foreign Bible Society, Cambridge University Library, BSA E3/6/2/3.

[2] T.H. Darlow and H.F. Moule (eds.), Historical catalogue of the printed editions of Holy Scripture in the library of the British and Foreign Bible Society (London: The Bible House, 1903).

[3] A.S. Herbert (ed.), Historical catalogue of the printed editions of Holy Scripture in the library of the British and Foreign Bible Society (London: British & Foreign Bible Society, 1968).

[4] A Short-Title Catalogue of Books printed in England, Scotland & Ireland and of English Books Printed Abroad, 1475-1640, ed. A.W. Pollard, G.R. Redgrave, W.A. Jackson, F.S. Ferguson, and K.F. Pantzer, 2nd ed., 3 vols (London, 1976-91), vol.1, p. 86.