Medievalism in fin de siècle Paris: a new acquisition

One of the more enjoyable parts of curating the Library’s collection of rare books is adding new (old) books to our shelves, in areas which students and researchers using our collections might find useful. New acquisitions might fill gaps in holdings of authors of whose work we hold extensive collections, from Erasmus and Montaigne to Laurence Sterne and Rousseau. They might also cover any number of subject areas where we have existing strengths, thanks in part to generous donations and bequests of past collectors, including Enlightenment literature, Irish and Dutch printing, and illustrated books. One area of interest which has developed in recent years is in more recent printing (perhaps eighteenth or nineteenth century) which was inspired by artwork and script found in medieval manuscripts, of which the Library has an important collection. Not only does such an approach allow us to see how later ages were inspired by the past, but it also creates connections between media; in this case, medieval manuscript and printed books.

One recent addition in this area was spotted by my colleague Dr James Freeman (Medieval Manuscripts Specialist) in a catalogue put together by bookseller Justin Croft (a familiar face to avid watchers of Antiques Roadshow) to mark Bastille Day. The volume contains all fourteen issues of a journal entitled Gazette du Vieux Paris, published to coincide with the 1900 Paris Exposition. This world’s fair was held from 14 April to 12 November 1900 to celebrate the achievements of the past century and to look toward development into the next. Visited by 51 million people it was the sixth of ten major expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937. The site was vast, as seen in the aerial view above, covering 280 acres from the esplanade of Les Invalides to the Eiffel Tower (itself built for the 1889 Exposition).

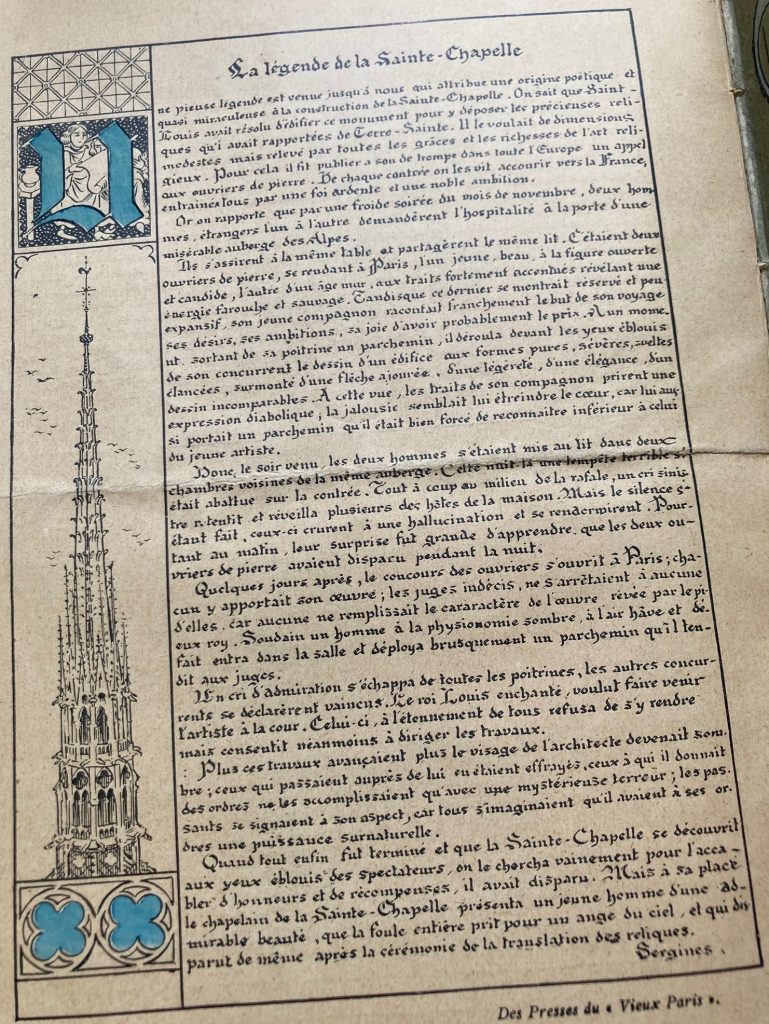

The Gazette was produced in conjunction with the exhibit ‘Le Vieux Paris’, designed by Albert Robida and one of the most popular of the entire Exposition: a miniature city built along the right bank of the Seine, intended as a tribute to Parisian architecture of the past. Divided into three quartiers, the architecture covered the fifteenth, sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Shops were staffed by individuals in period costume, selling cakes, fancy goods and stationery, and there were three restaurants. One shop even boasted a printing press! In the words of Elizabeth Emery who has studied the exhibit and its importance in the growth of French interest in the past: ‘Using the popular exhibit as a device for celebrating national achievement, he [Robida] inspired widespread appreciation of French heritage, thereby invigorating a nascent conservation movement … [it] reflected a turning point in the French nation’s understanding and representation of its architectural heritage’ (‘Protecting the past: Albert Robida and the Vieux Paris exhibit at the 1900 World’s Fair’, Journal of European Studies 35/1, 2005, pp. 65-85). Such an appreciation of the past was key at this point in Parisian history: plans for the Paris metro (which began to operate in the year of the Exposition) included the demolition of ancient buildings to make way for ground-level (rather than underground) tracks.

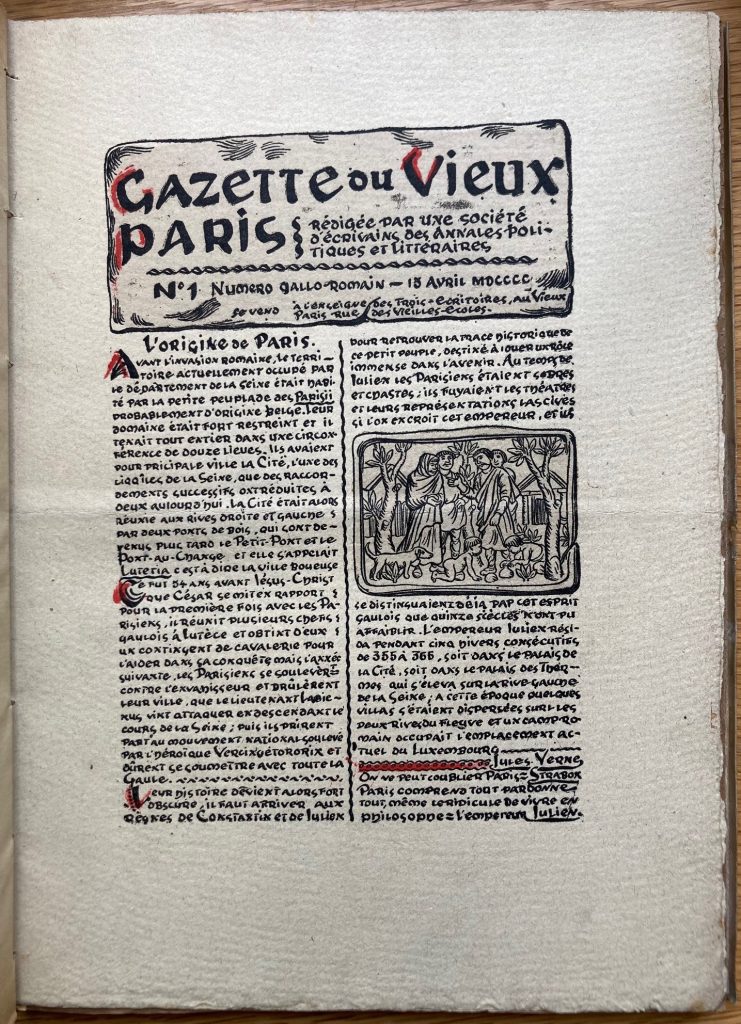

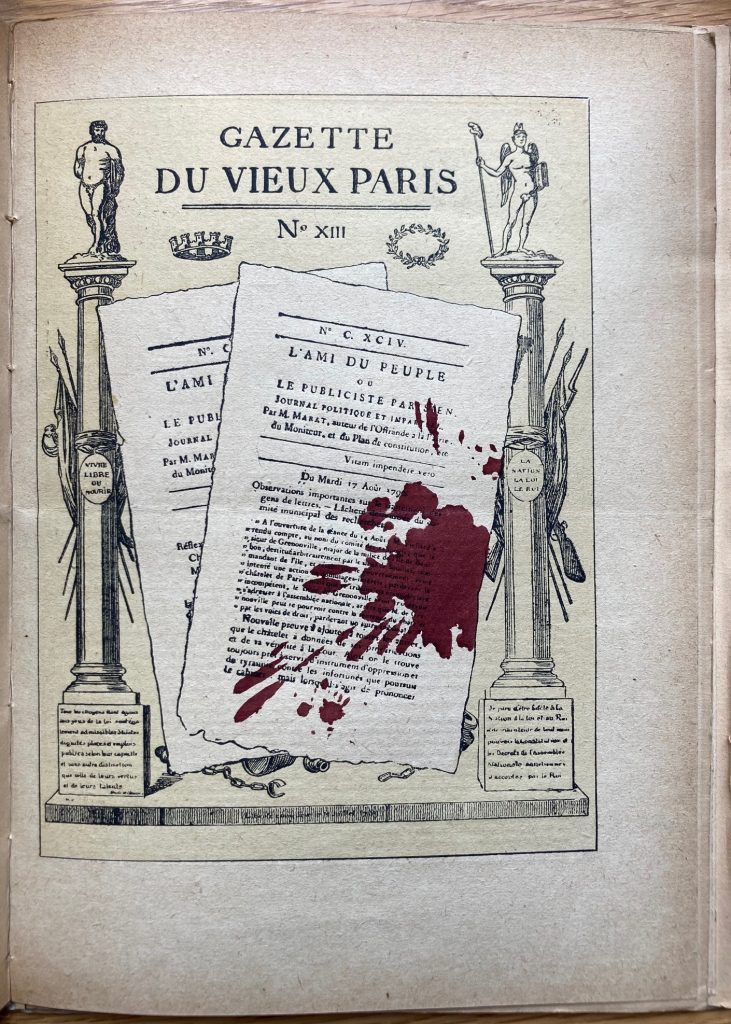

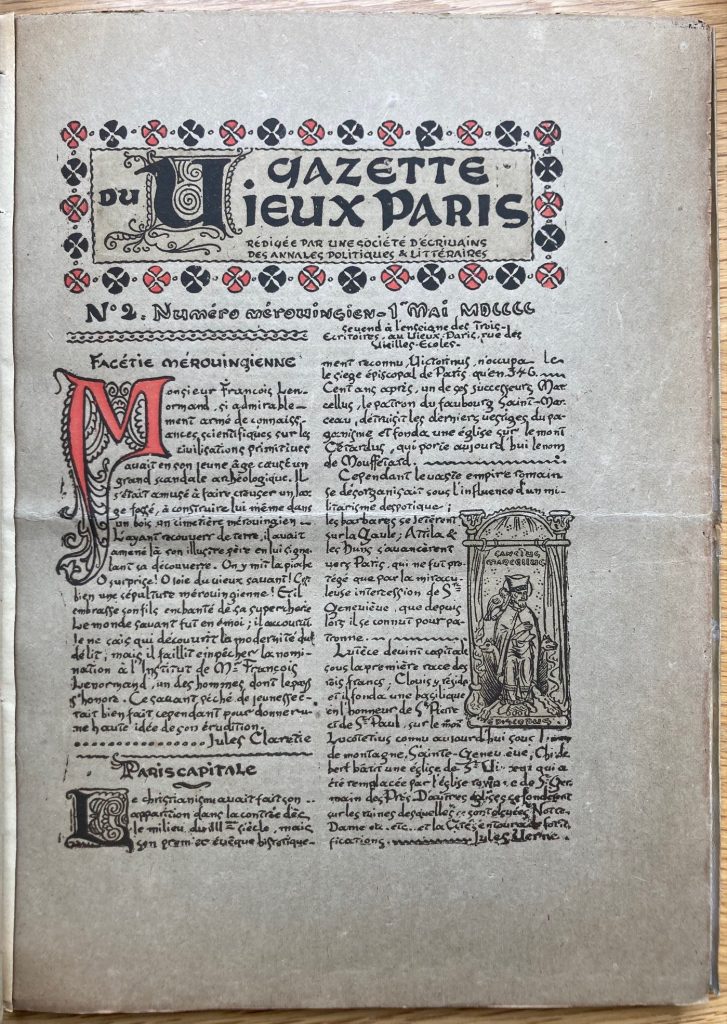

Each number of the Gazette is designed and presented in a different style from a period in French history: beginning with Gallo-Roman, Merovingian and Carolingian, and ending with the Revolution of the late eighteenth century and Napoleon. The earlier issues use handwriting styles appropriate to the period, and include decorative initials and borders in the style of medieval manuscripts. Contributors to the text include some important figures in French literature: Jules Verne, Pierre Loti, and Anatole France.

The issues in the set acquired by Library appear to have spent some time folded in half; perhaps bought during the Exposition by Dr Jean Munzenberger, whose bookplate can be found on the inside cover but about whom little is known (it was probably Munzenberger who had the issues bound together, with striking marbled endpapers, by a binder named Thiebaut). The set is now rare (the only other copy in the UK is at the British Library) and our copy is now catalogued and available to researchers in the Rare Books Room, where it sits alongside other works illustrated by Albert Robida in the same style. These include his La nef de Lutèce (see below), which illustrated the defining events in Parisian history in the style of a medieval manuscript.