John Argentine: Cambridge physician and royal doctor

If you have not yet visited the University Library’s exhibition, Curious Cures: Medicine in the Medieval World, don’t worry: as of today, you have two months left! Tickets are free and you can book your slot via the UL website.

Most of the manuscripts that are on display were the subject of a Wellcome-funded project to digitise, catalogue and conserve manuscripts across Cambridge’s libraries that contain medical recipes (a handful of others and some early printed books have also been included). All of these are now available to view on the Cambridge Digital Library, alongside detailed descriptions of the textual contents, material characteristics, origins and provenance. Many are also accompanied by introductions written either by members of the project team or guest contributors whose paths have crossed with these manuscripts in the course of their research. When you visit, if one catches your eye, you can find out more by searching for its classmark, which is given at the bottom of the label.

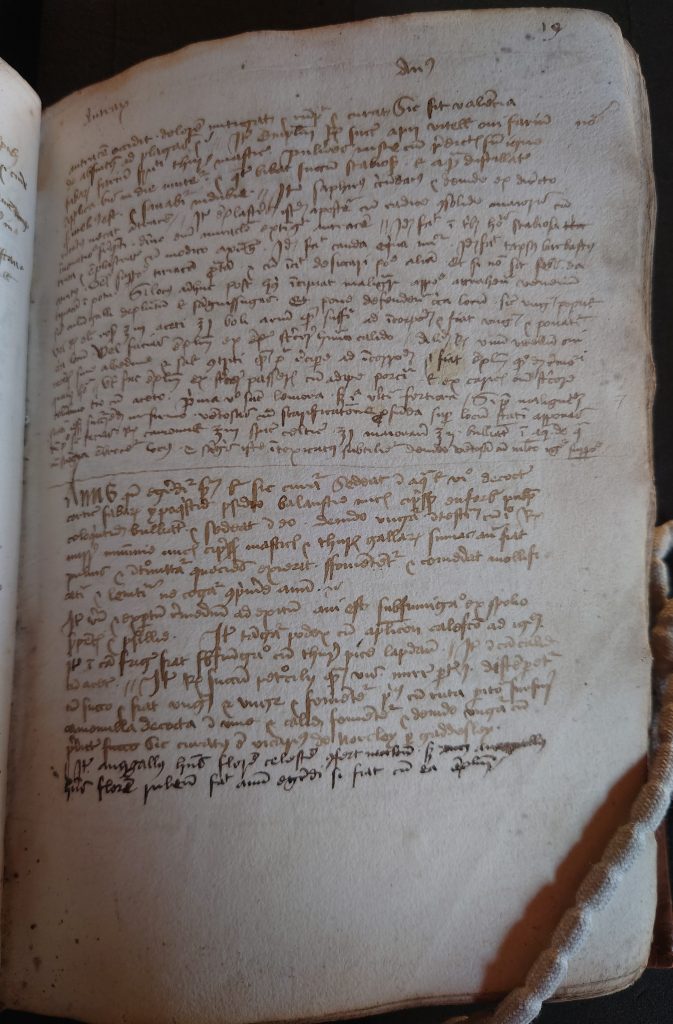

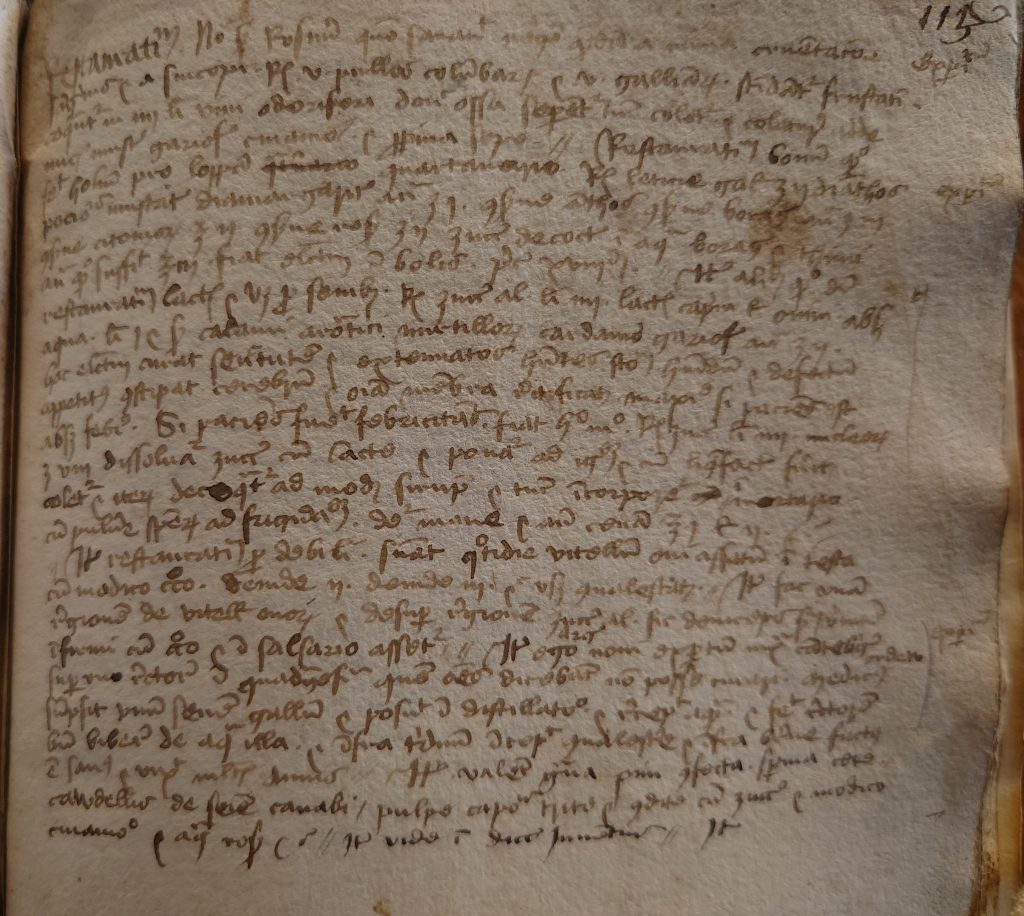

Remedies for ‘Antrax’ (virulent ulcers/boils) and problems of the anus

There is one exception, however…This particular manuscript comes not from the UL, the Fitzwilliam Museum or one of the college libraries, but from the Bodleian Library in Oxford (classmark MS Ashmole 1437). This is the first time a manuscript has been loaned from their collections for an exhibition at the UL — and we are hugely grateful for their generosity! A casual viewer might think it worthy of little attention, though: it isn’t richly illuminated, it’s made of paper not parchment, and the text is written in a small neat hand on tightly packed lines. So why the excitement?

This book of medical recipes belonged to and was copied by John Argentine (c. 1443–1508), an important figure in the history of medicine in Cambridge. Argentine was born in Bottisham, a village six miles to the east of the city. After time as a pupil at Eton, from 1457 he studied at King’s College, one of only three colleges at which the teaching of medicine was supported (the others being Peterhouse and Gonville Hall). Medicine was a higher faculty, meaning students had first to graduate as Bachelor of Arts, and it was pursued by a very small proportion of the University’s scholars. Indeed, many students went abroad to pursue such education at more renowned centres of medical learning, especially in Italy and southern France. Argentine was among them: between 1473 and 1476, his name is absent from records at King’s College, and there is evidence of his presence in Ferrara and possibly Padua too. After a brief return to Cambridge, Argentine entered royal service as physician to Richard III and then to Henry VII and his eldest son, Prince Arthur.

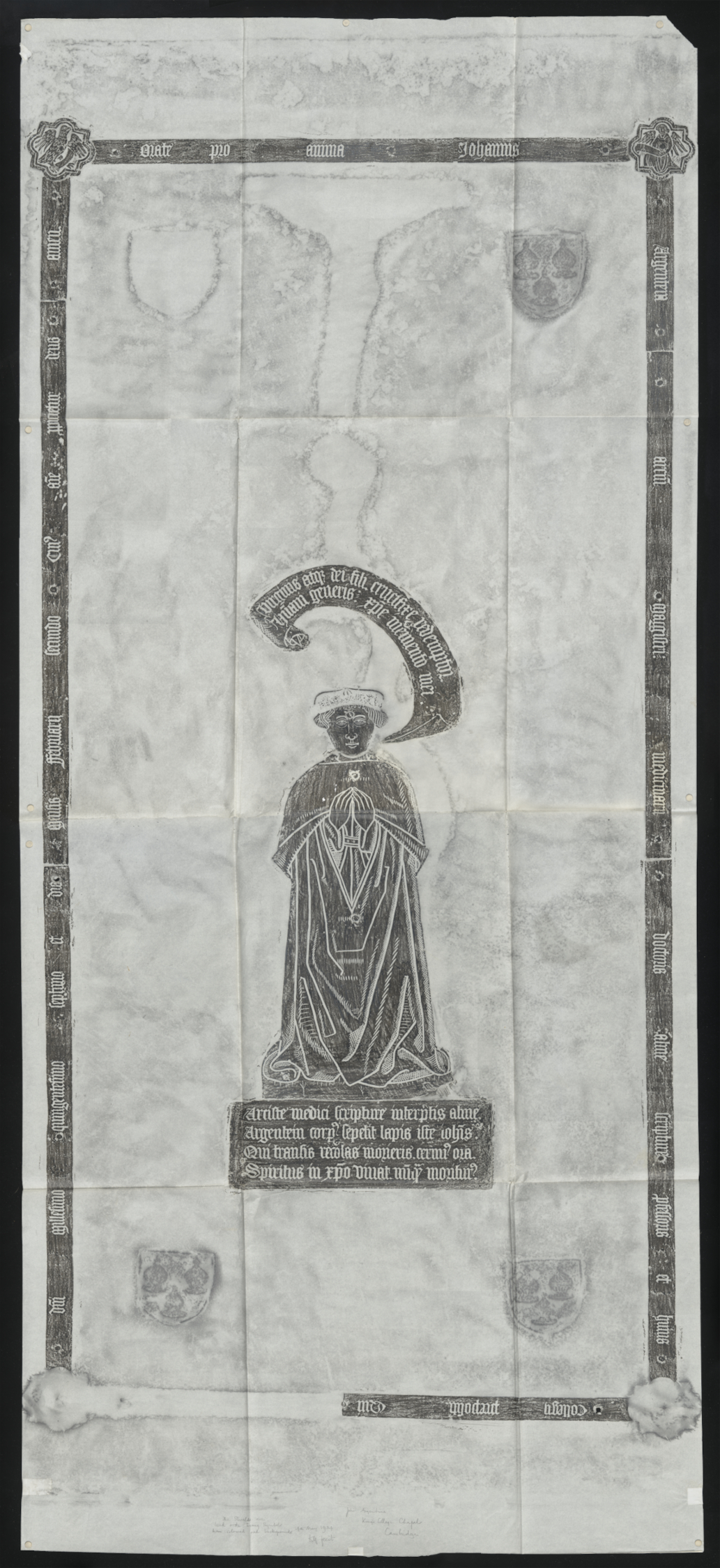

A rubbing taken from John Argentine’s memorial brass (UL, Maps.Brass Rubbings.Cambridgeshire.1).

In 1501, Argentine was elected Provost of King’s and returned Cambridge for the remaining seven years of his life. He was buried in the college chapel and left instructions in his will of how he wished to be commemorated. The memorial was to show him ‘beside a picture of our saviour Jesus Christ on the cross’, his hands folded in prayer, and supplied the words that should appear on a speech scroll as well as beneath him. This was cut in brass and set into a stone slab on the floor of a side chapel, and survives largely intact. The crucifix above his head has gone, as has one coat of arms; the other shows three medicine jars. The text in the frame reads:

Pray for the soul of John Argentine, master of arts, doctor of medicine, preacher of scripture, and provost of this college. Who [died in the year] of the Lord 1407* and on the second day of the month of February. On whose soul may God have mercy. Amen.

[* The discrepancy in date arises from the practice of counting the start of the calendar year not from 1st January but from 25th March. ]

The brass obviously could not be moved and is not readily visible to visitors to King’s College Chapel. Fortunately, Cambridge University Library is home to an extensive collection of brass rubbings — probably the largest in the country after the Society of Antiquaries’. Members of the UL’s Cultural Heritage Imaging Laboratory photographed our rubbing of Argentine’s brass and it was reproduced on vinyl and fixed to the floor next to where the manuscript is displayed. Peter Jones observed that Argentine’s instructions were followed in full, except perhaps his specification that the memorial be ‘non egregius aut sumptuosus’ (not showy or costly). Certainly, it will have been cheaper than a stone monument, but it must be among the largest surviving monumental brasses. It is one of only eight extant examples that depict physicians.

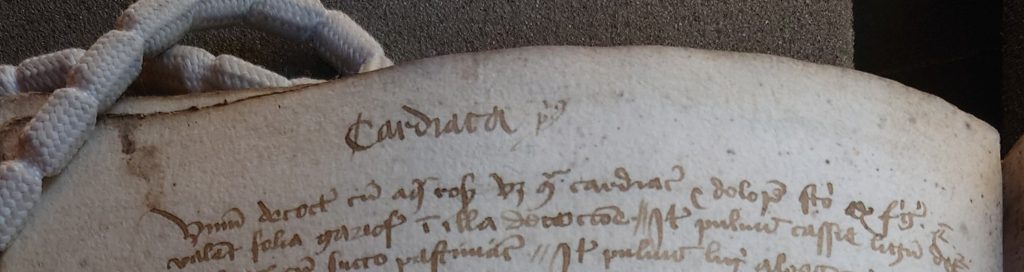

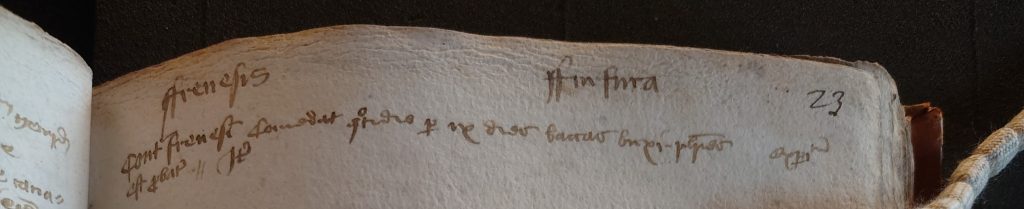

At least nine other books were owned or can be connected with Argentine, but the Bodleian’s manuscript is unique among them in providing first-hand testimony of his work as a physician. The basic structure, and much of the initial contents, are derived from an earlier compendium of medical recipes, the Tabula medicine, which was assembled by English Franciscan friars between 1416 and 1425. Argentine wrote out the headings in larger script — mostly disease names, in alphabetical order — and recorded potential cures underneath.

Item expertum cantebrigie in Magistro Reynolds […] . Item expertum apud Ware […] . Item expertum apud cantebrigie in mulieris […] .

These are not only culled from other books, however. Argentine noted down remedies that he had learned about, seemingly by report rather than from a written source. Among these are a recipe for a ‘marvellous powder’ that restored a person’s vision, ‘proven on a certain prior who was hardly able to see and in a short time he was healed perfectly’, or three separate cures for flux that were proven on ‘Master Reynolds’ and an unnamed woman in Cambridge and on another patient in Ware. Treatments used by women rather than on them appear in several places, such as this for kidney stones:

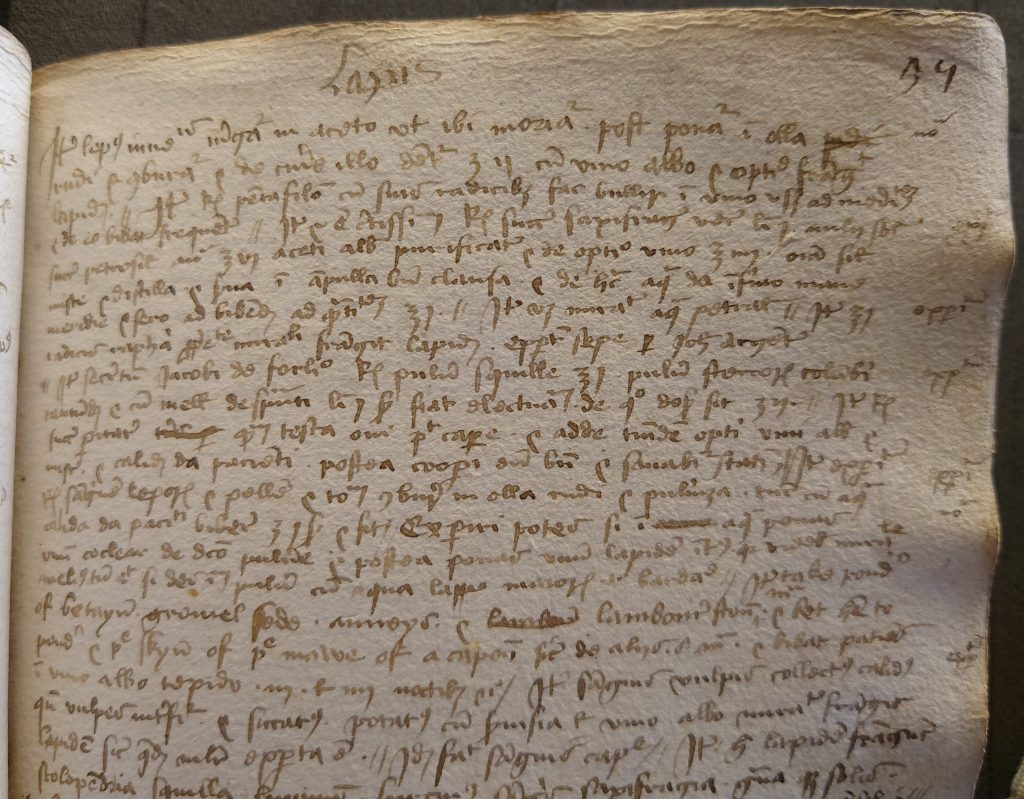

Remedies for ‘Lapis’ (the stone). The one quoted below is on the last three lines shown. Note that it is preceded by another written mostly in Middle English, whereas the majority of remedies are written in Latin.

Item sanguis vulpis, collectus calidus quando vulpes interficiuntur, et siccatus, potatus cum seruisia et vino albo, mirate frangit lapidem. sic quodam muliere experta est.

The blood of a fox, collected warm when foxes are being killed, and dried, drunk with beer and white wine, breaks up the stone marvellously. Thus proven by a certain woman.

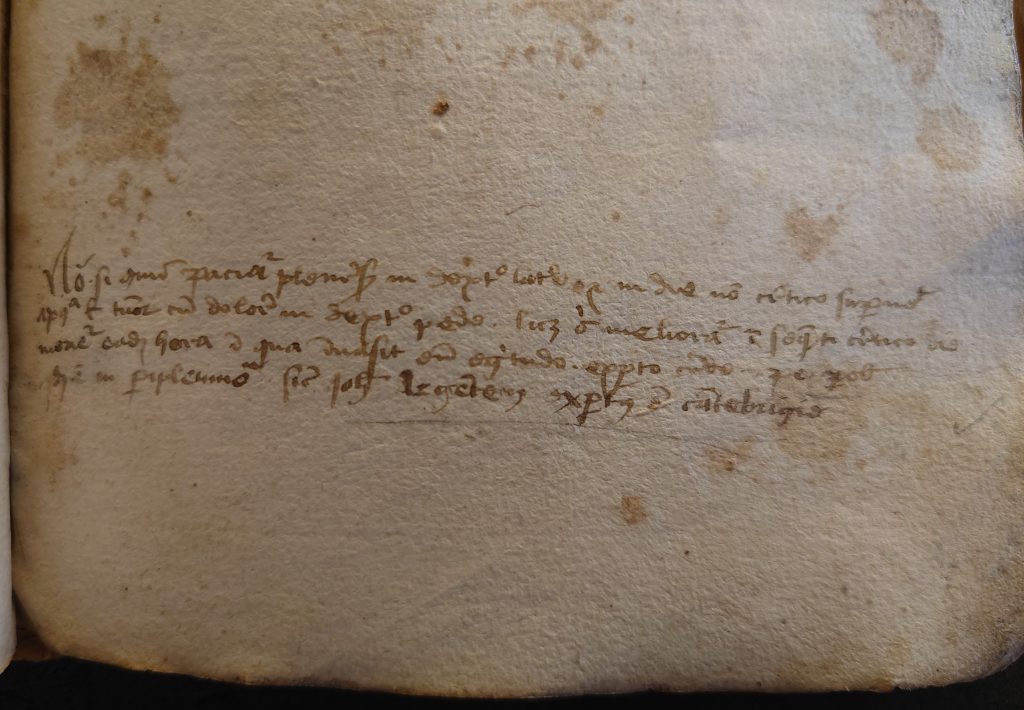

In one remarkable instance, he bears personal witness to the successful healing of a patient. In the section on ‘restoratives’ — medicines intended to bring someone back to health — he wrote at the beginning of one recipe that ‘I, John Argentine, know this worked’. He went on to describe how one of his teachers at King’s, William Ordew, administered what sounds rather like chicken soup ‘near Cambridge, to a rector in his fortieth year, whom all were saying could not be cured’:

The remedy quoted here begins seven lines from the bottom

Item ego \argentine/ noui expertum iuxta cantebrigie super vno rectore in quadragesima quem omnes dicebant non posse curari. Medicus \Ordew/ sumpsit vnum senem gallum et posuit in distillatorio et recepit aquam et fecit rectorem bene bibere de aqua illa et infra triduum incepit conualecere et infra breue factus est sanus et vixit multis annis.

The doctor, Ordew, took an old cockerel and placed it in a distillatory [a kind of alchemical flask] and retained the water and made the rector drink well from that water and within three days he began to regain his health and within a short time he was made well and lived for many years.

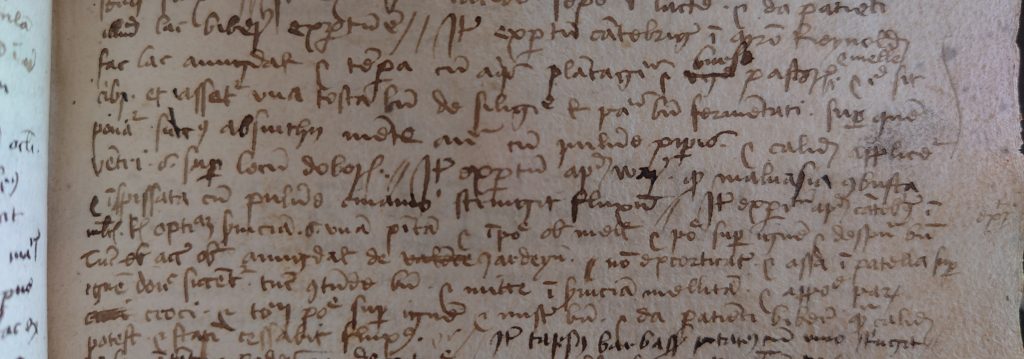

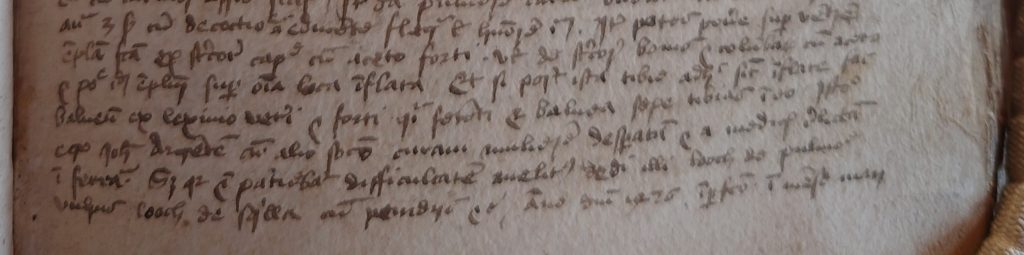

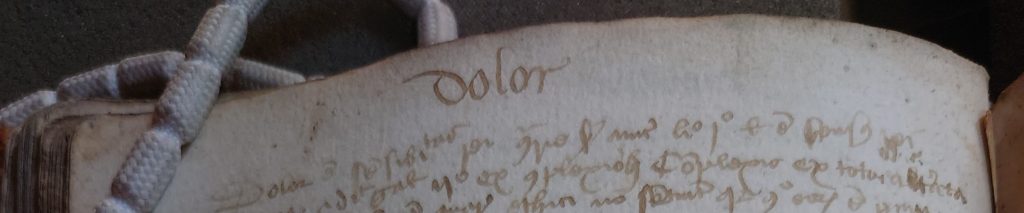

A cure for dropsy administered by Argentine and an associate to a woman in Ferrara.

What makes the notebook especially valuable, however, are the glimpses it provides of Argentine’s own medical work. Against many entries, Argentine wrote the word ‘experimentum’ (often in a heavily abbreviated form). Rather than an ‘experiment’ in the modern sense, these ‘experiences’ may be evidence of Argentine trying remedies he had recorded and noting when he found them to be effective. There are also a number of remedies that Argentine claimed to have devised himself. Besides shedding light on his medicinal creativity, these entries provide some valuable biographical information. At the end of a page of cures for dropsy, he wrote that ‘I, John Argentine, with another companion, cured a woman desperate and forsaken by physicians in Ferrara […] in the year of the Lord 1476 […] in the month of May’. The following year, back in Cambridge, Argentine healed a longstanding sufferer of a case of gonorrhoea:

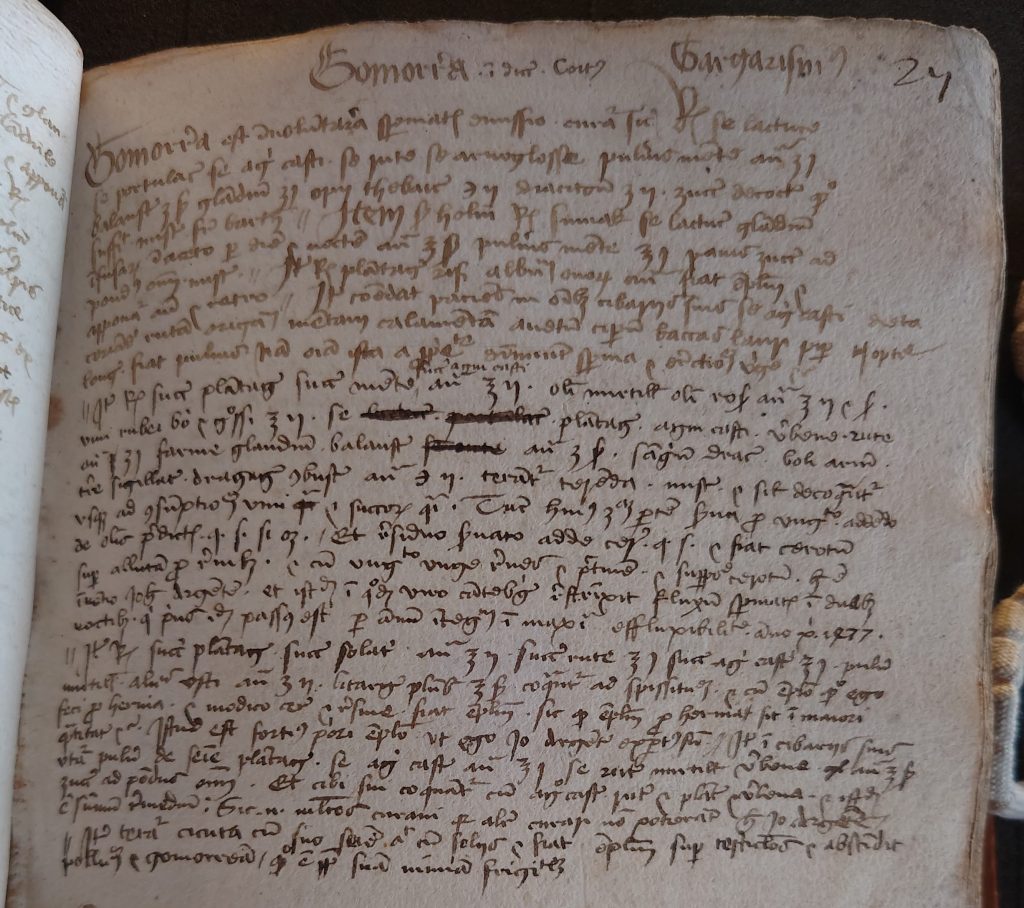

The remedy quoted here begins ten lines from the top (where the darker ink starts)

Take juice of plantain, juice of mint, juice of chaste-tree, each ounces ii, myrtle oil, rose oil, each ounces ii and a half, good full-bodied red wine, ounces ii, plaintain, chaste-tree, vervain and rue, each drachm i, acorn flour, pomegranate flower, each half drachm. Burn dragon’s blood, armenian bole, terra sigillata, and tragacanth, each scruple ii, grind them and blend together, then boil up until the wine is evaporated and it has almost become a juice. Then put aside one third to be added to the ointment made from the aforesaid oils, as much as needed, as is appropriate. And to the remaining two thirds add as much wax as needed and make a wax plaster over tawed leather for the kidneys. Apply the ointment to the kidneys and chest and put the plaster on top. This is the invention of John Argentine and when I tried it on a man in Cambridge in 1477 it restricted the discharge of sperm after two nights, when he had previously suffered major discharges for a whole year beforehand.

[My thanks to Peter Jones for his assistance in translating this recipe.]

In the Curious Cures exhibition, Argentine’s notebook is joined in its case by four other medical manuscripts, all of which were used or owned by Cambridge physicians, all of whom knew one another or were connected in some way. The first is a compendium of Galen’s writings that had been donated the previous century to the library of Peterhouse (Peterhouse MS 33). It was annotated by William Hatteclyffe (d. 1480), who — alongside William Ordew — was one of Argentine’s teachers. Hatteclyffe was admitted as a fellow of Peterhouse in June 1437 at the same time as Roger Marchall (c. 1417–1477), whose hand is found in the next two manuscripts (Peterhouse MSS 222 and 231). The second of these contains an inscription recording its donation to Pembroke College by John Somerset (d. 1454), who was a fellow there 1410–1418. Somerset had served as physician to Henry VI 1427–1451, in which capacity he was succeeded by Hatteclyffe from November 1452. Marchall and Hatteclyffe knew one another professionally: they both served Edward IV and, with a third royal doctor, sat on a panel in 1468 to examine the case of Joanna Nightingale of Brentwood, who had been accused by her neighbours of being a leper (she was exonerated).

Marchall was a wealthy man, as much from investments in his family’s trading activities as from fees earned as a physician. His hand has been identified in more than forty surviving manuscripts (including two more identified during the course of the Curious Cures project). He left books to Peterhouse, Gonville Hall and King’s. Some, presumably those that went to Peterhouse, later found their way into the hands of Thomas Deynman, doctor to Lady Margaret Beaufort and (like John Argentine) Henry VII. The fourth manuscript in the case contains his ownership inscription written underneath a table of contents added by Marchall’s hand (Peterhouse MS 95). Deynman was the first physician to be elected Master of the college (and one of only two in its history). He bequeathed ‘twenty of his better books’ to the college, which remembered him fifty or so years later by commissioning a posthumous portrait as part of a series commemorating the institution’s masters. This has kindly been loaned to us from the Master’s Lodge at Peterhouse.

A remedy for pleurisy proven by John Argentine in Cambridge

These manuscripts illustrate a culture in which books were acquired, annotated, shared, gifted and bequeathed, where connections to colleges and to colleagues were remembered through the books that these men had read and had owned. In this respect, Argentine stands somewhat apart from his contemporaries. Some of his books are still to be found in the libraries of Gonville and Caius College, Peterhouse and St John’s, but there is no evidence that they went there directly, and in any case the latter was founded three years after his death. His will mentions neither books nor Cambridge. Yet Argentine’s ‘self-citation’ in his book of remedies is particularly noteworthy at a time when few personal testimonies of medical practice survive. Most medical recipe texts were circulated anonymously, either in compilations or as paratextual additions; even those integrated into medical treatises by named authors were not necessarily their own creations. ‘Ego Argentine’ aligned the writer with other authorities he cited, while differentiating from their work treatments he had seen or created personally. This is puzzling, insofar as the manuscript seems intended only for Argentine’s own reference. There is no evidence that he shared it with others and the few annotations by other hands sit separately to Argentine’s notes, in blank spaces at the bottom of the leaves, and are probably later additions. Perhaps it appealed to clients to be offered cures he had personally devised and used, yet by placing himself so visibly in the text Argentine ensured that future readers would remember his activities, whether he intended this or not.

If you would like to learn more, Peter Jones will be talking to the Society for the History of the University on ‘John Argentine (c. 1433–1508: royal doctor, alchemist and Provost of King’s’. The meeting will take place at 5.30pm on Thursday 20 November in the John Bradfield Room in Darwin College. Refreshments will be offered from 5.00pm — and all are welcome!

For further reading about Argentine, see:

- Peter Jones, ‘John Argentine (c. 1443–1508), physician and college head’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004): https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/642

- R.B. Davis and J.A. Davis, ‘Monumental brasses of British physicians’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 28 (1973), 243–256: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24623007

- D.R. Leader, ‘John Argentein and learning in medieval Cambridge’, Humanistica Lovaniensia, 33 (1984), 71–85: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23973239

- D.E. Rhodes, ‘Provost Argentine of King’s and his books’, Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 2 (1954-58), 205–12: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41337020

- D.E. Rhodes, John Argentine, provost of King’s: his life and his library (Amsterdam, 1967)

Good starting places for the other Cambridge physicians — William Hatteclyffe, John Somerset, Roger Marchall and Thomas Deynman — are their entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004):

- Rosemary Horrox, ‘William Hatteclyffe (d. 1480), physician and diplomat’: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/12603

- Carole Rawcliffe, ‘John Somerset (d. 1454), physician and courtier’: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/26012

- Linda Ehrsam Voigts, ‘Roger Marchall (c. 1417-1477), physician and writer on medicine’: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/45763

- Carole Rawcliffe, ‘Thomas Denman (d. 1500/01), physician’: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/52671

Images of Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 1437 reproduced by kind permission of the Bodleian Libraries.