In their own words: medical writings in Middle English

There is just one month left to visit the University Library’s current exhibition, Curious Cures: Medicine in the Medieval World. The display closes on 6 December — so this is your last chance to see a selection of medical manuscripts from the collections of Cambridge University Library and several college libraries! Tickets are free and you can book your slot via the UL website.

As you might expect, the majority of the manuscripts on display contain texts written in Latin. During the medieval period, and indeed for some time thereafter, Latin was the international language of scholarship. It was used for the composition and communication of all manner of written works, medicine among them. However, you will also see many books whose contents are written in the vernacular language of later medieval England: what we nowadays call ‘Middle English’.

Frontispiece to Troilus and Criseyde, showing a figure — probably intended to represent Geoffrey Chaucer — standing in a pulpit and reciting his work to an assembled audience of noblemen and noblewomen (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 61, f. 1v, inset)

This is the same language that renowned poets like Geoffrey Chaucer, Thomas Hoccleve and William Langland used in their writings, and is the language of famous but anonymous works such Gawain and the Green Knight or Pearl, and the ‘mystery plays’ that adapted and re-enacted episodes from the Bible. Consequently, we tend to think of ‘vernacular writing’ in terms of these canonical writers and works of poetry and prose and drama. However, there existed alongside such ‘literary’ outputs a vast quantity of practical writing in Middle English. This is much less widely known, perhaps because it seems more mundane or less imaginative, its language rooted in the needs and necessities of daily life: how to cure someone’s bad breath, treat a horse suffering from glanders, cook a partridge or pheasant, or make various pigments or ink, for instance.

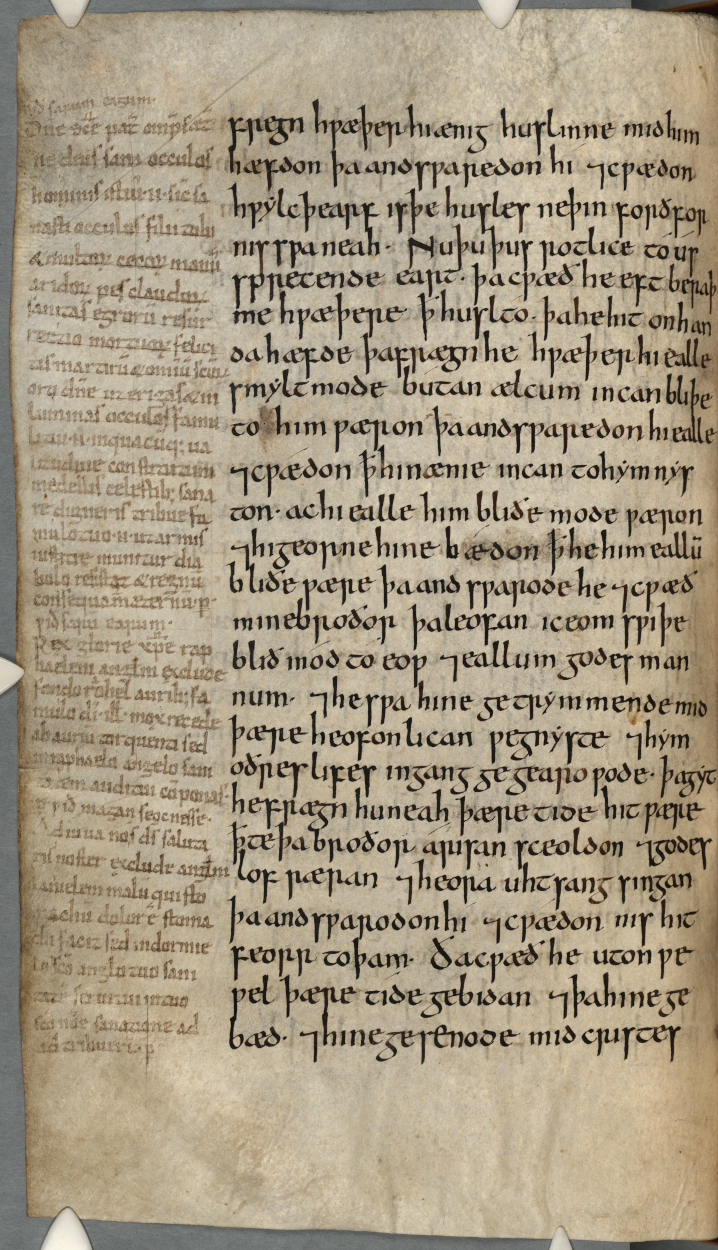

Medicinal prayers for sore eyes, sore ears and illness, in Old English, written in the margin (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 41, p. 326)

In England in particular, there was a long tradition of medical writings being circulated in the vernacular, stretching back to before the Norman Conquest. For example, the Curious Cures project included a manuscript at Corpus Christi College — a translation into Old English of Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica made in the first half of the eleventh century — into whose margins various hands added medicinal charms, prayers and remedies dealing with sore eyes and ears, illness and childbirth.

Most of the manuscripts on display are from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, however. This partly reflects how manuscript collections in Cambridge developed in the post-medieval era. For various reasons, there was a particular interest in the native languages of England among the early antiquarians and collectors, such as Matthew Parker and Richard Holdsworth, who gave their libraries to Corpus Christi College and the University of Cambridge respectively. It is also a consequence of patterns of survival. Much more material survives from the late medieval period, but not only because it is closer in time to the present than the pre-Conquest era. Literacy was increasing and thus the supply of and demand for written works, including those in the vernacular. The production of books was becoming secularised: it was no longer the preserve of monasteries and other centres of religious learning, but was being done by lay craftsmen for pay and profit. The materials and techniques used in these processes were also becoming cheaper or more efficient: the introduction of paper offered (in certain respects) a less expensive alternative to parchment, and the adoption of cursive scripts speeded up the process of copying texts.

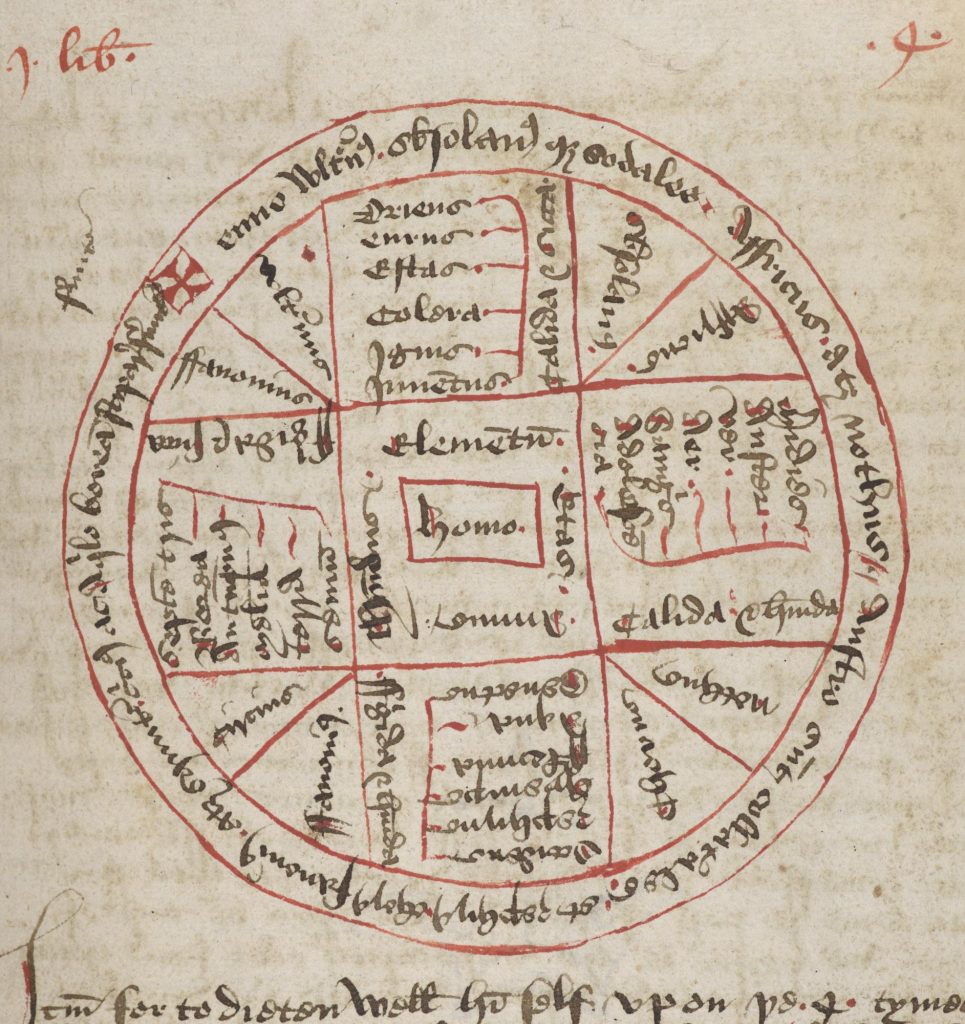

Diagram of quaternities, illustrating the shared characteristics (hot/cold and dry/moist) of the humours, regions, winds, seasons, elements and stages of life, in Henry Daniel, Liber uricrisiarum (Cambridge, University Library, MS Ff.2.6, f. 17r)

Some of these vernacular medical writings were original compositions. One of the most important is the Liber uricrisiarum, the earliest known work of academic medicine in Middle English. It was composed and revised from c. 1375 to 1382 by Henry Daniel, a Dominican friar, writer and horticulturalist. As the title suggests, it is a treatise on uroscopy: diagnosing illness by examining a patient’s urine. First, Henry defines what urine is and how one should examine it; then, the twenty different colours one could observe; and finally the contents of the urine itself. Though little is known of Henry’s life or education beyond what he mentions himself, he was evidently well-educated: the Liber uricrisiarum drew on the works of Latin, Greek and Arabic writers, the latter probably known through intermediate Latin translations.

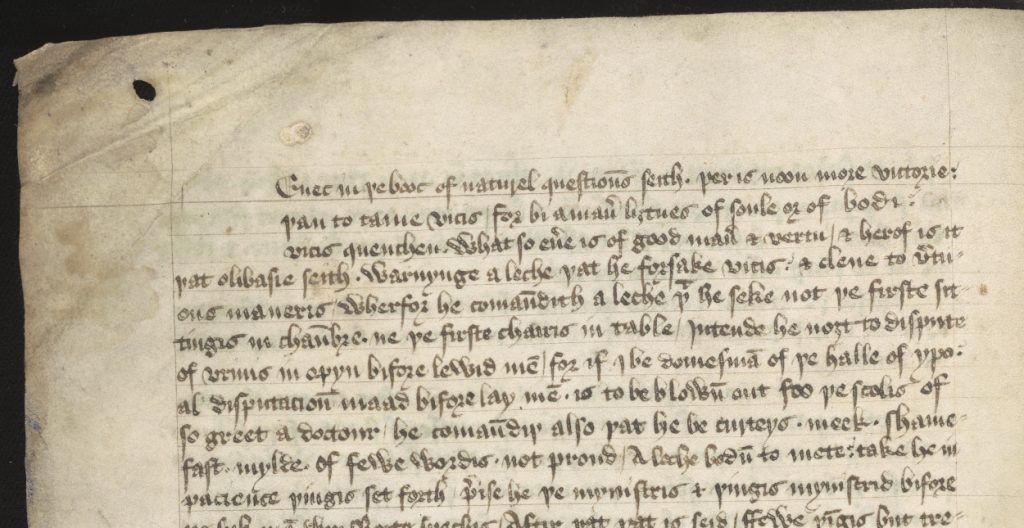

The beginning of a treatise on the conduct of ‘leeches’, advising how they should ‘forsake vices and cleave to virtuous manners’ (Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College, MS 451/392, p. 20, inset)

Another example is the only surviving copy of a short treatise on the proper behaviour of a healer or ‘leech’. It deals first with his conduct as a professional in the context of the strict social hierarchies of the time: the leech should not seek precedence at the dinner table, and he should be ‘courteous, meek, shamefast, mild, of few words, not proud’. He must be respectful to his hosts and not bad-mouth their servants, nor openly criticise the opinions of other medics in attendance. It might surprise readers to find that a good bedside manner was also considered important. The leech should not tax the patient with too many questions if he is feeling frail, and he should comfort him and encourage him to place his faith in God. The patient should be in restful and pleasant surroundings, entertained by musicians or visits from friends, though ‘either be they still or only speak they such things shortly that please the sick’. Particular emphasis was laid upon the personal cleanliness of the leech, too: he should avoid eating pungent spices or garlic so his breath does not smell, his hands and nails should be clean, and he should wash his hands often in front of the patient.

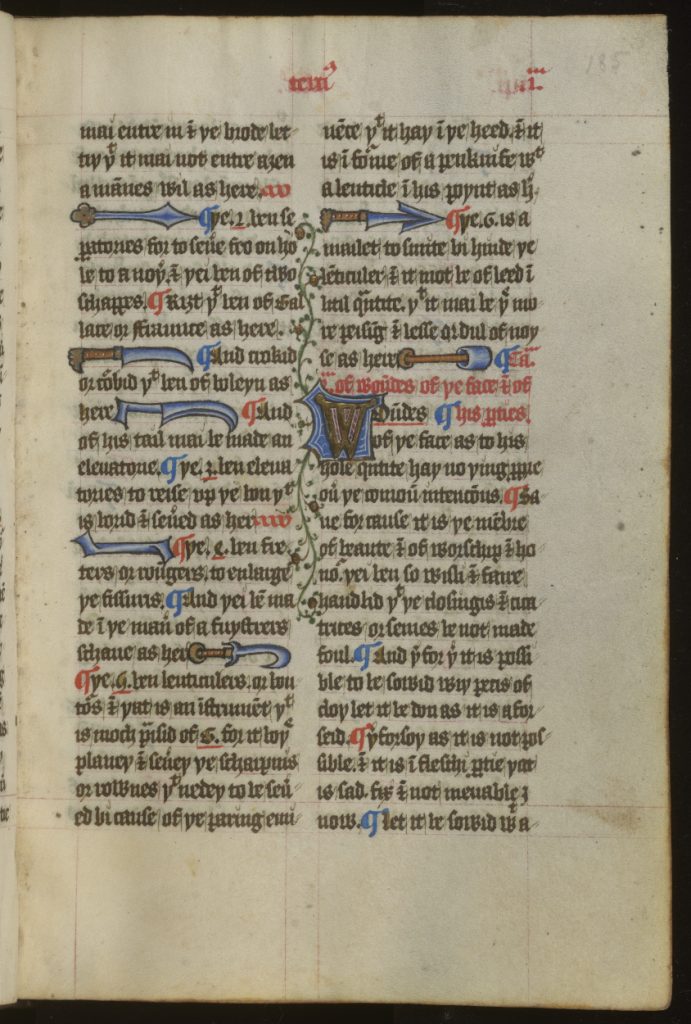

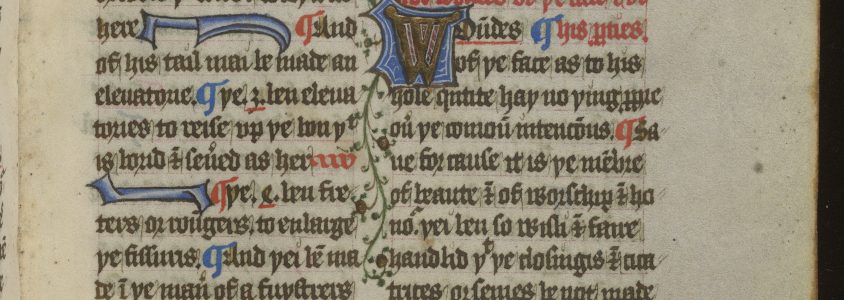

Tools for the surgical treatment of skull fractures and head wounds, from a Middle English translation of Guy de Chauliac’s Chirurgia magna (Cambridge, Jesus College, MS Q.G.23, f. 185r)

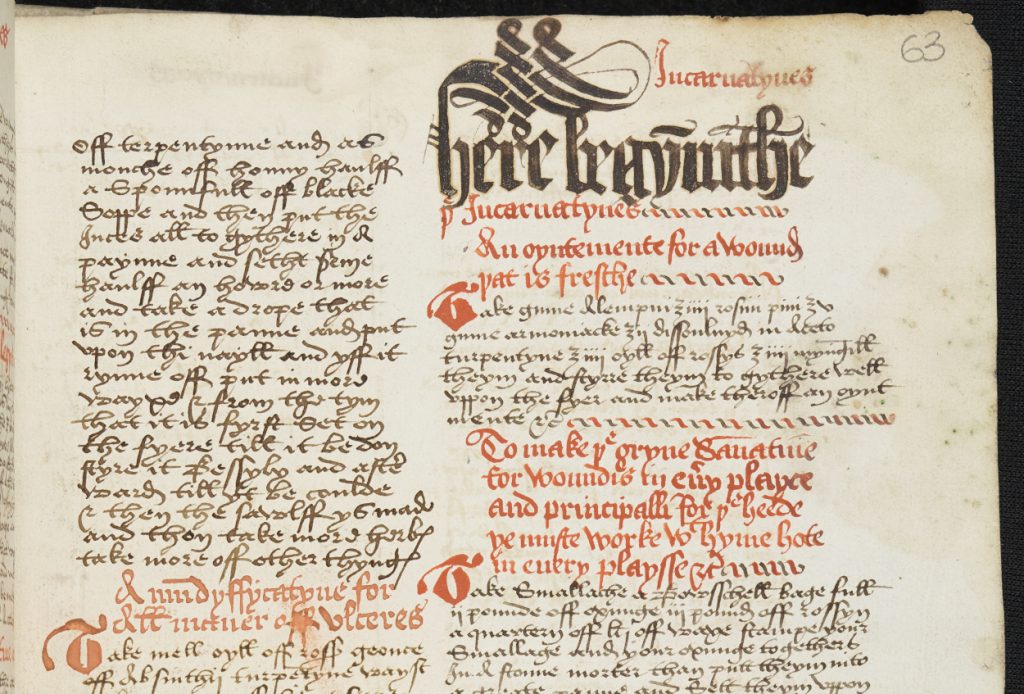

Many of the Middle English texts on display are translations — and, to varying degrees, adaptations — of texts that had been transmitted in other languages. One of these is a Middle English version of Guy de Chauliac’s comprehensive introduction to surgery, the Chirurgia magna, which had originally been composed in Latin. It is the only complete copy of one of three different renderings of the text in Middle English. The text is neatly written in a formal, textura bookhand and ornamented by illuminated initials: it was evidently produced for a wealthy patron. Most notably, the treatise is illustrated at various junctures. An artist has added in-line drawings of surgical instruments that are described in the text. In the image above, you can see how they have used shading to give three-dimensional form to such tools as creparies, separatories, an elevatory, a fretter, a lenticular and a mallet — all of which were used for treating skull fractures and wounds to the head.

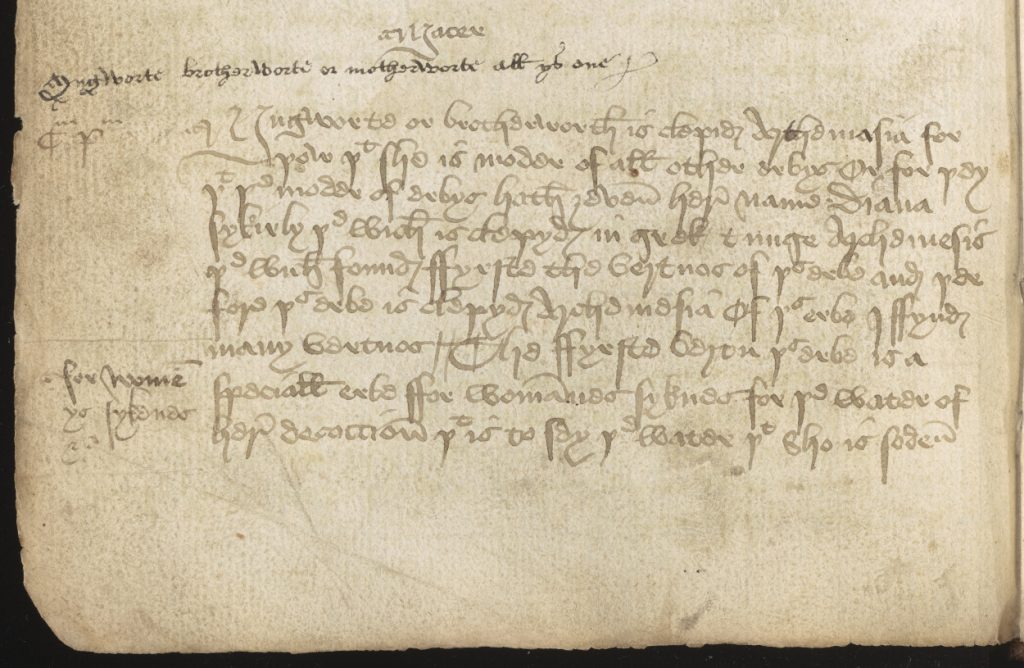

On the virtues of mugwort or artemisia, from a Middle English translation of Odo of Meung, De viribus herbarum (Cambridge, University Library, MS Ee.1.15, f. 24v, inset)

Another example is entitled simply ‘Macer’. This was the name of a Roman poet, Aemelius Macer (d. 16 B.C.), who wrote a poem describing remedies for poisonous snakebites. It was adopted as a pseudonym by a French cleric, Odo of Meung, who explained the medicinal uses of over seventy different plants in an extended poem entitled De viribus herbarum. In its Middle English iteration, however, the text has been converted into prose. It begins with mugwort, southernwood, wormwood, nettle, plantain and so on, and, like its source, advises which parts of a plant should be picked, when and for what purpose. Visitors to the exhibition may be surprised to find that it is not illustrated, but few medieval herbals were: their purpose was not the identification of plants, but the description of their properties.

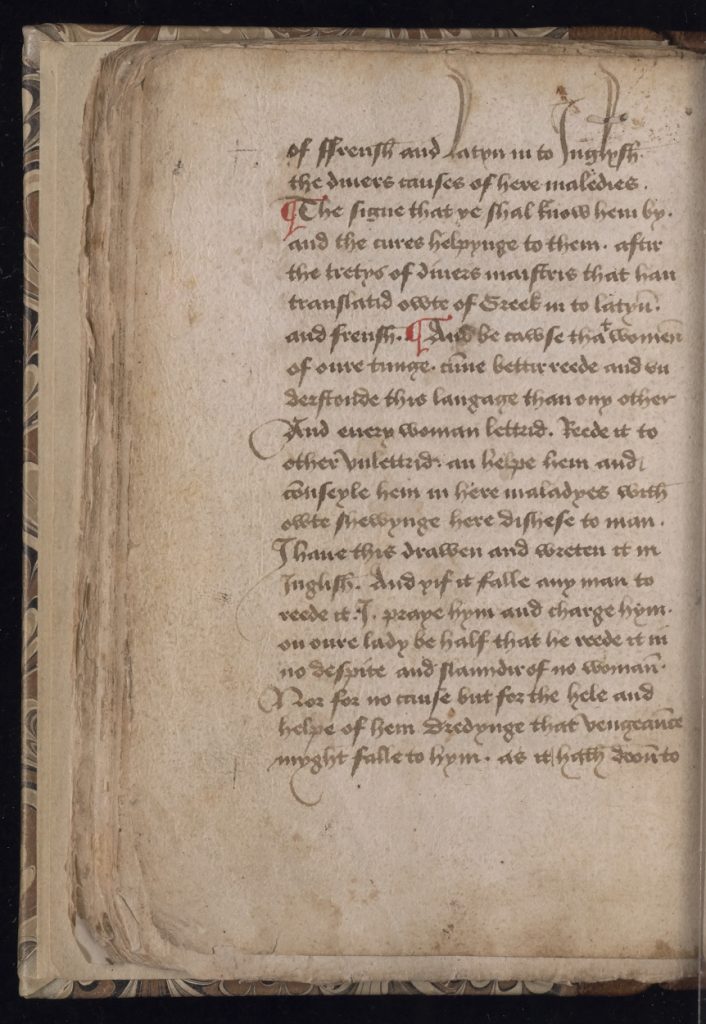

A justification for translation into Middle English and the role of women as medical caregivers and teachers, from the Knowing of Woman’s Kind in Childing (Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.6.33, f. 2:1v)

Sometimes, texts were translated only in part and their contents rearranged for new purposes. That is the case with The Knowing of Woman’s Kind in Childing. It is the earliest Middle English translation of extracts from the ‘Trotula’ and other sources. The ‘Trotula’ is a group of three texts, two on gynaecology and one on cosmetics, which emerged in southern Italy in the 12th century. One of these, De curis mulierum, was attributed to a female writer known as Trota of Salerno. Knowing was probably written by a male cleric, but ostensibly addresses a female readership. It emphasises the role of women as caregivers and midwives, but also as readers and mediators of the written word. The author explained why he wrote in the vernacular: ‘And because that women of our tongue can better read and understand this language than any other […] I have drawn and written it in English’. He also issued an admonition: ‘And every woman lettered [i.e. literate]: read it to other unlettered and help them and counsel them in their maladies without showing their disease to men.’

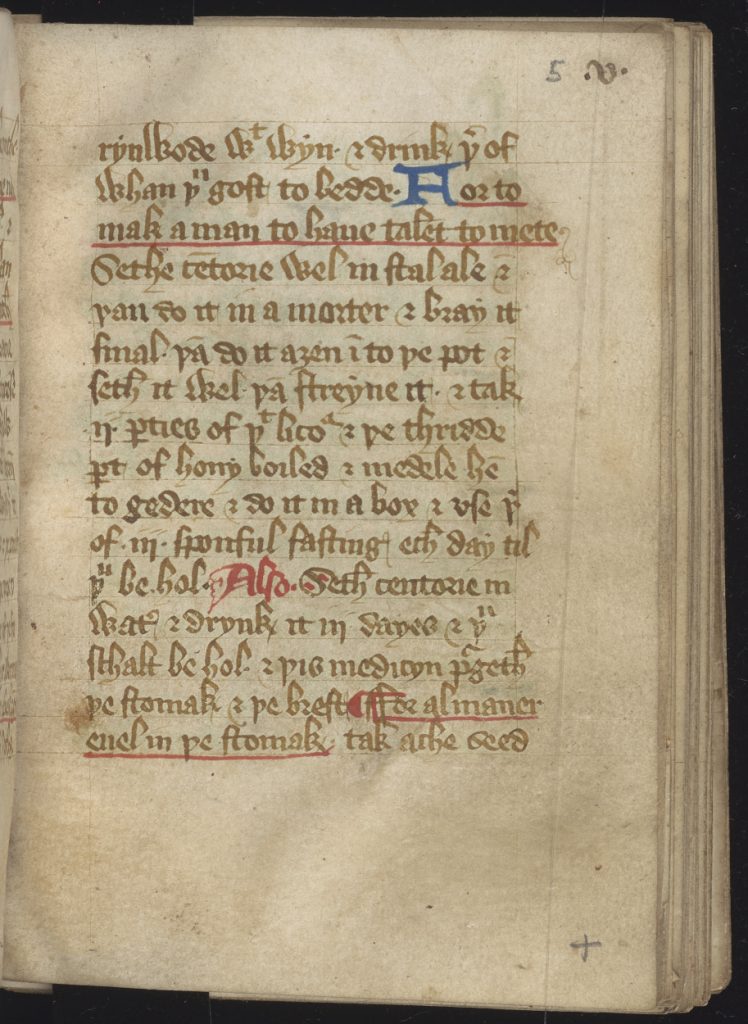

It is recipes, however, that are by far the most numerous form of medical writing in Middle English. These short, instructional texts for curing one ailment or another are in a category of their own. They fall somewhere between original compositions and translations, and much research remains to be done on identifying their sources, translation and transmission. A major obstacle to this is the sheer quantity of surviving examples: there are in excess of 8,000 individual texts across the 190 manuscripts covered by the Curious Cures project. Many are scattered across manuscripts containing medical or non-medical texts, written in the margins, endleaves or other blank spaces, and have been painstakingly recorded in freshly prepared catalogue entries.

Two compilations of medical recipes in Middle English, similar in contents but different in presentation (Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 9308 and MS Add. 9309)

The recipes are most densely concentrated in dedicated compendia that sometimes comprise over 50, 100 or even 200 individual items. These are commonly organised in ‘head to toe’ order: beginning with such problems as headaches, migraine, blurred vision, loss of hearing and nosebleeds and working down to aching knees, swollen ankles and gout (though this structure is rarely adhered to rigidly). Two manuscripts illustrate the contrasting forms in which such compilations are found: one apparently a production by a professional scribe and complete with a prefatory poem that proclaims the utility of the contents (above left), and another that survives in its medieval wrapper and seems altogether more ‘home-made’ (above right).

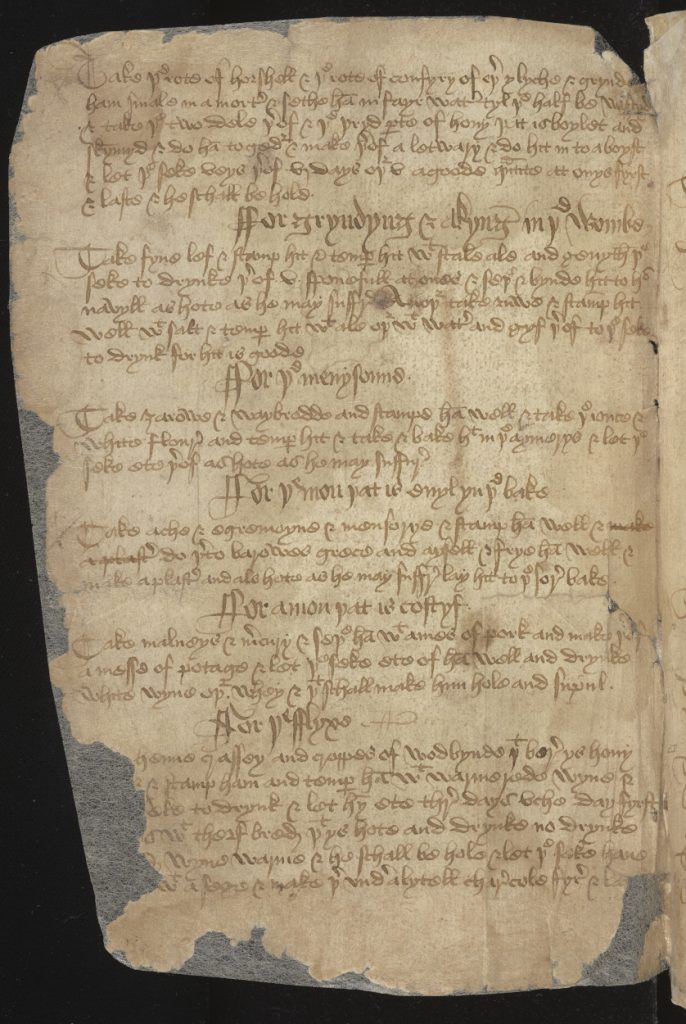

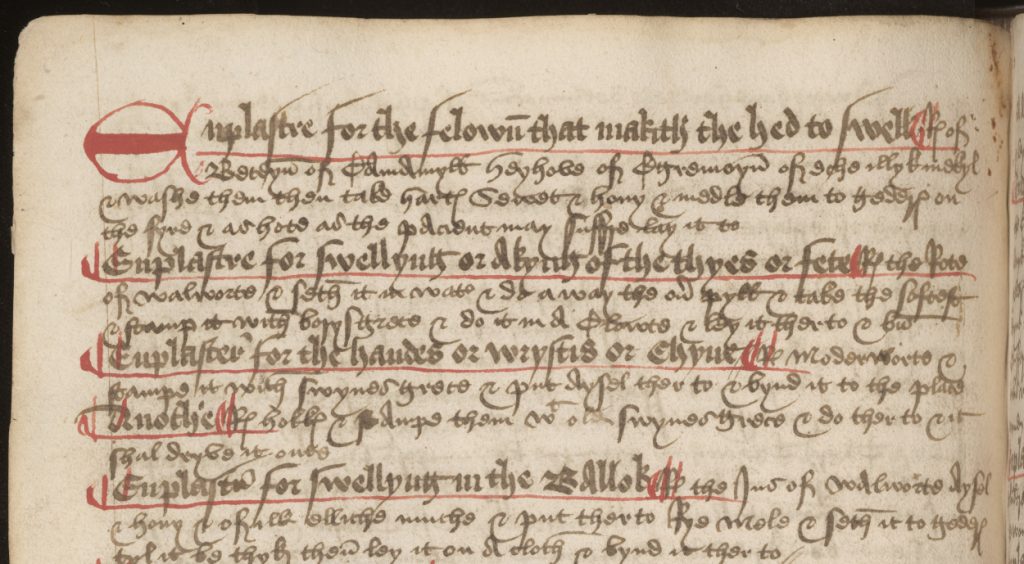

Collections of remedies by type of medicinal preparation: plasters for various swellings (Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College, MS 457/395, f. 34v, inset) and mundificatives and incarnatives (Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O.9.32, f. 63r, inset)

There were alternative modes of organising medical recipes, however: in a couple of manuscripts, they are presented according to category or genre. These capture the wide range of medicinal preparations that were available to healers in the late medieval period. Common examples include waters, oils, balms, salves, unguents, pills, draughts, powders, electuaries, syrups and plasters. However, in both of these examples, there are also medicines that are less familiar to the modern reader: repercussives, resolvatives, mundificatives, incarnatives, retentives, caustics, and desiccatives. These are all concerned with the cleansing and healing of wounds, a particular specialism of medieval surgeons, who were likely owners of these two books.

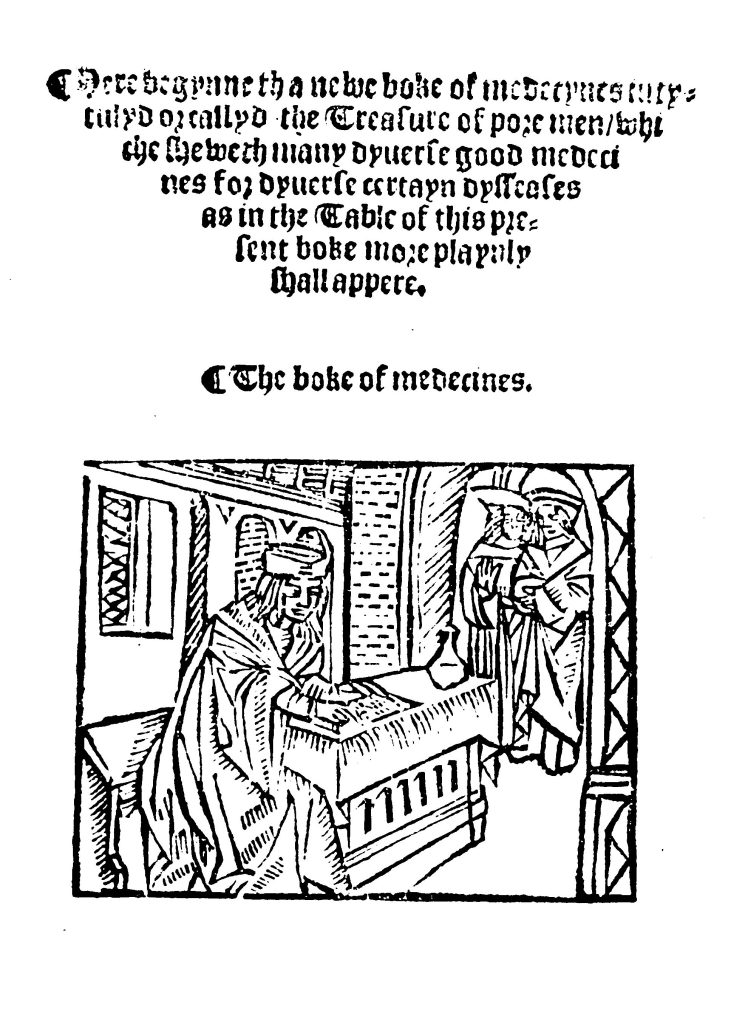

Frontispiece to the Treasure of Pore Men, with a woodcut showing a physician at his desk (scan of microfilm from San Marino, Huntington Library, 59451; copy on display in the exhibition is Cambridge, University Library, Sel.5.175)

The production and consumption of these medical recipes continued long after the end of the medieval period. The early printers in particular were quick to spot a ready market for simple medical advice. One example is The treasure of poor men, its title imitating that of a widely circulated compilation of the 13th century, the Thesaurus pauperum of Petrus Hispanus. Although it was billed as a ‘newe boke of medecynes’, it in fact reproduced many of the same remedies found in earlier handwritten compilations. Around the same time, its enterprising printer Richard Bankes issued a herbal, A New Macer, and a treatise on uroscopy, The Saying of Urines, all produced in similar format and dimensions. At the end of the latter, he advertised this fact, stating to his readers: ‘All they that desire to have knowledge of medicines for all such urines as be before in this book, go to the herbal in English or to the book of medicines, and there you shall find all such medicines that be most profitable for man.’ The owner of the UL’s copy evidently followed this advice, buying all three together and having them bound in one volume.

Images from manuscripts reproduced by kind permission of the Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge; the Master and Fellows of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge; the Master and Fellows of Jesus College, Cambridge; and the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.