A Lost Ballad Found: Rediscovering a Jephthah Ballad in the Norton Collection

A guest post by Dr John Colley, Research Fellow in English at St John’s College, Cambridge.

In 2023 I began working on an edition of a little-known, anonymous English manuscript translation of Sallust’s War with Catiline (1st century BCE), witnessed only in CUL, MS Nn.3.6 (now published as The Coniuracion of Lucius Sergius Catelina: An Early Tudor Translation of Sallust’s ‘Bellum Catilinae’). As preparation for that edition, I consulted as many copies of Sallust’s War with Catiline printed between 1470 and 1520 as I could find: I knew that the anonymous translation must date from around the turn of the sixteenth century and wanted to know how contemporary print editions of Sallust’s history had been annotated by English readers.

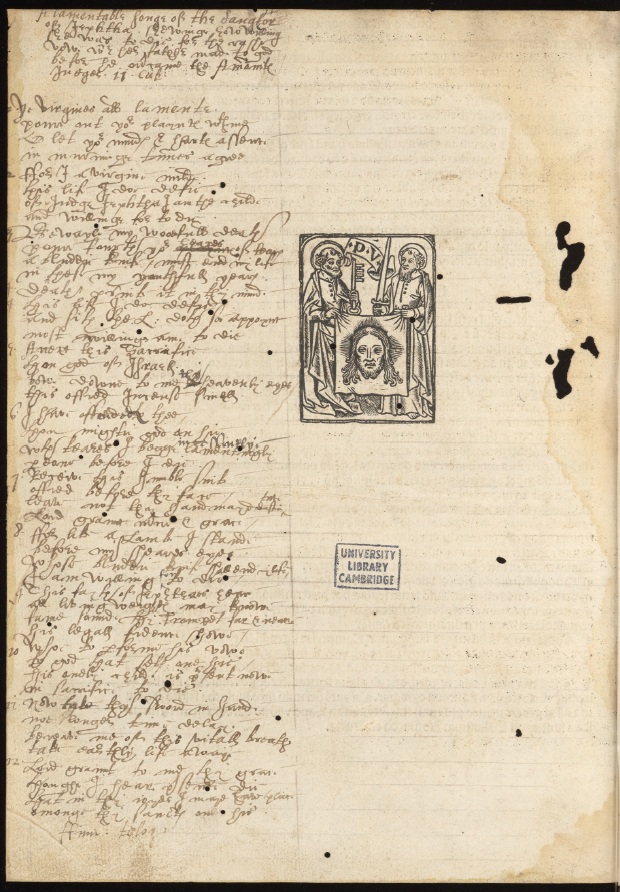

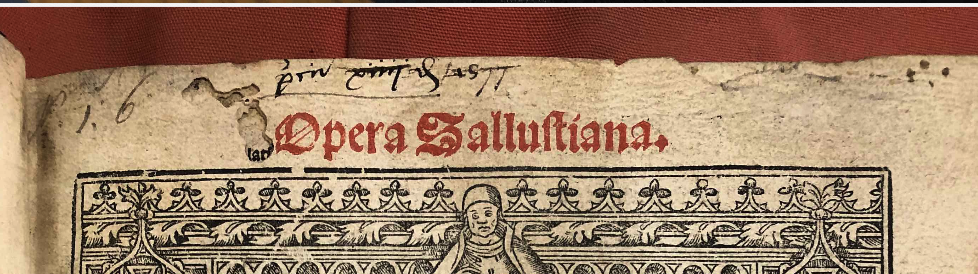

Many copies were indeed annotated. Sallust was the most popular ancient historian in late-fifteenth and early sixteenth-century Europe, and his often-moralizing works were widely read in schools. They were also read as manuals for princely or noble readers, since they were considered to contain some of the secrets of success in military and political affairs alike. Sadly I never found an edition whose annotations were obviously by the anonymous translator of MS Nn.3.6. In one Lyon copy of Sallust’s works from 1517, however, I stumbled across something surprising and perhaps equally interesting: a manuscript copy of a hitherto unnoticed Tudor ballad in the voice of Jephthah’s daughter. The book is shelved as Norton.b.4, and it was acquired by the University Library in 1984 from the collection of the Cambridge librarian F. J. Norton (1904–1986). An annotated transcription and introduction to the ballad has recently been published as ‘A Lost Ballad Found: “A Lamentable Songe of the Daugtor of Iephtha” (ca. 1567–1568)’, Studies in Philology, 122 (2025). I’m grateful to the journal for permission to discuss a few of my findings in this blog post.

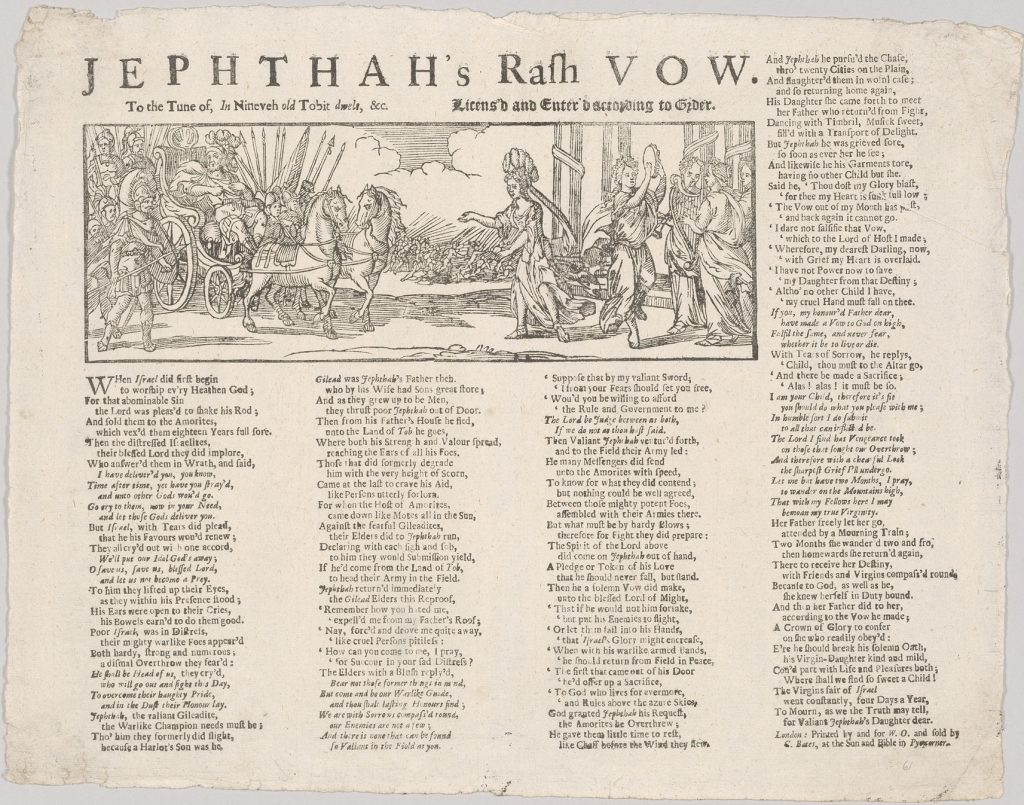

The Old Testament story of Jephthah’s daughter, from Judges 11, is tragic. Jephthah is an Israelite general who promises to God that, if he proves successful in battle against the hostile Ammonites, he will offer a burnt sacrificial offering of whatever he first sees on his return home from war. Jephthah is successful, but on his return is first greeted by his (unnamed) daughter, whom he feels compelled to sacrifice to keep his vow—and he does sacrifice her, in the view of most commentators.

The story was a popular one in early modern England, often because it was assumed to teach the virtues of womanly and filial obedience that many contemporaries cherished. There were plays and poems on the topic and also other ballads. This hitherto unnoticed text in Norton.b.4 is striking, however, as the only early modern text to present the story entirely from the perspective of Jephthah’s daughter: she underscores how willing she is to die so that her father can keep his vow to God. The Norton text probably predates other ballads on the topic. Indeed the Norton ballad can very probably be identified and dated as ‘the songe of Jesphas Dowgther at his death’, hitherto thought lost, which was entered in the Stationers’ Register between 22 July 1567 and 22 July 1568. Ballads—written to be sung to well-known tunes—were typically printed on single broadsheets and were easily destroyed by re-reading and re-use. This is far from the only ballad which survives exclusively in manuscript, having presumably been copied from a now-lost printed broadsheet.

A date of 1567–8 for this ballad is also consonant with other evidence, such as its style and apparent date of being copied into Norton.b.4. The script, for instance, is late Elizabethan. The date ‘1577’, which is close in time to the entry in the Stationers’ Register, is also inscribed on the titlepage of the book.

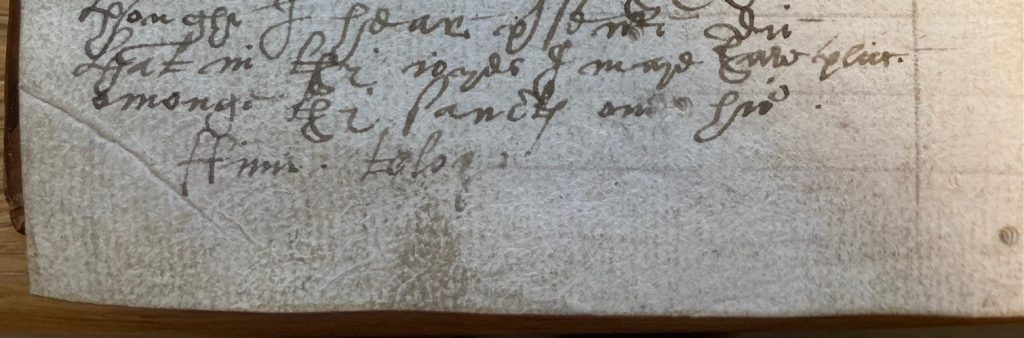

Perhaps it’s still surprising, however, to find this vernacular ballad—a genre often associated with ‘popular’ culture in Tudor England—in a copy of Sallust’s works in Latin. Indeed, similarities in script between the ballad and some annotations to the War with Catiline in Norton.b.4 suggest that the ballad scribe may also have read the Latin contents of this book. The ballad scribe even concludes his copy of the ballad not only with Latin ‘Finis’ (‘the end’), but also with this word’s Greek equivalent, ‘telos’. ‘Finis’ is usually how English ballads concluded; no surviving broadside ballad was concluded with ‘telos’. The Greek word’s addition here seems like a learned reader’s classicizing flourish. In Norton.b.4, then, English and Latin, classics and Old Testament history, and popular and elite culture all collide. This ballad’s scribe was apparently a reader of the classics and of at least one English ballad, and can be thanked for saving this ballad’s text from oblivion.

Bibliography:

John Colley, The Coniuracion of Lucius Sergius Catelina: An Early Tudor Translation of Sallust’s ‘Bellum Catilinae’, EETS os 366 (Oxford University Press, 2025)

English Broadside Ballad Archive, dir. Patricia Fumerton (University of California, Santa Barbara).

John Colley, ‘A Lost Ballad Found: “A Lamentable Songe of the Daugtor of Iephtha” (ca. 1567–1568)’, Studies in Philology, 122 (2025), 190–98.