Curious complexions: understanding and treating the skin in medieval England

This guest post is by Amelia Spanton, who recently finished her MA in Medieval Studies at the University of York.

There are now just two weeks left to visit the University Library’s exhibition, Curious Cures: Medicine in the Medieval World. The display closes on 6 December — so this is your very last chance to see a selection of medical manuscripts from the collections of Cambridge University Library and several college libraries. Tickets are free and you can book your slot via the UL website.

Medieval manuscripts contain an abundance of information about approaches to medicine and the body in this period, a great deal of which is now available online thanks to the digitisation and cataloguing work undertaken by the Curious Cures project. This wealth of evidence has been invaluable for my MA in Medieval Studies at the University of York. My dissertation, ‘The Complexion of the Soul: Understanding and Treating Skin in Late Medieval Medicine and Culture’, specifically focused on the portrayal and treatment of skin and complexion. I drew on two 15th-century manuscripts at Cambridge University Library — MS Add. 9308 and MS Ee.1.15 — whose recipes offer insights into medieval medical treatments and cultural understandings, particularly of the skin and complexion. As well as using these medical manuscripts, I also incorporated literary examples in order to explore different approaches to the appearance and health of the skin.

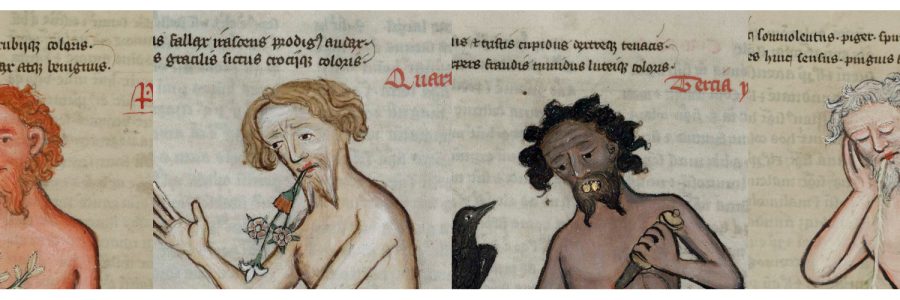

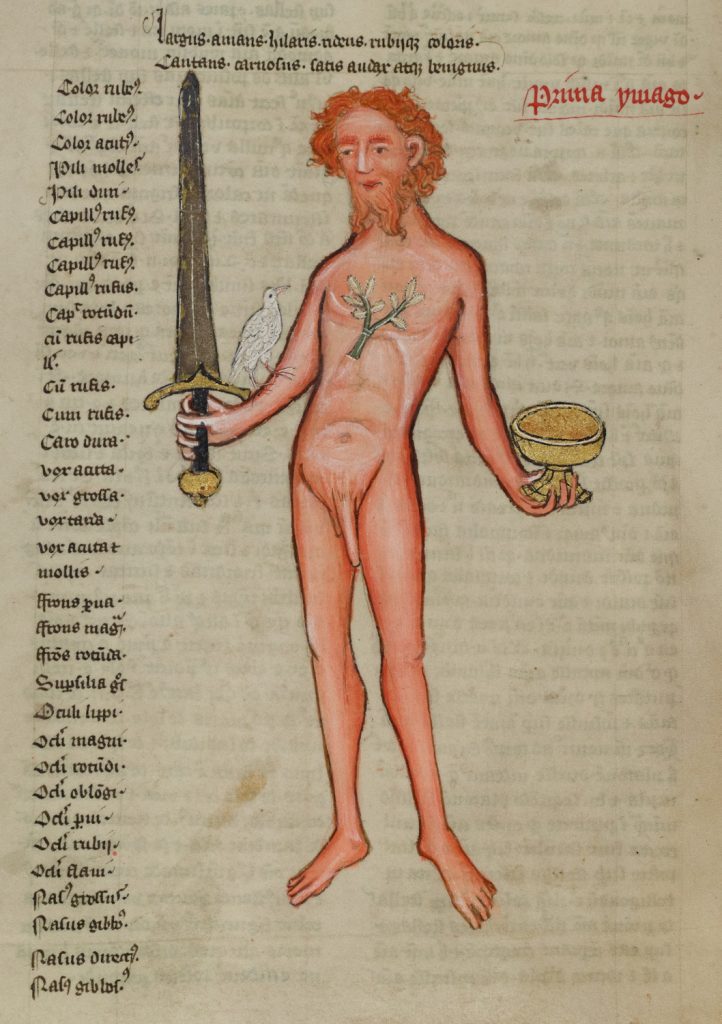

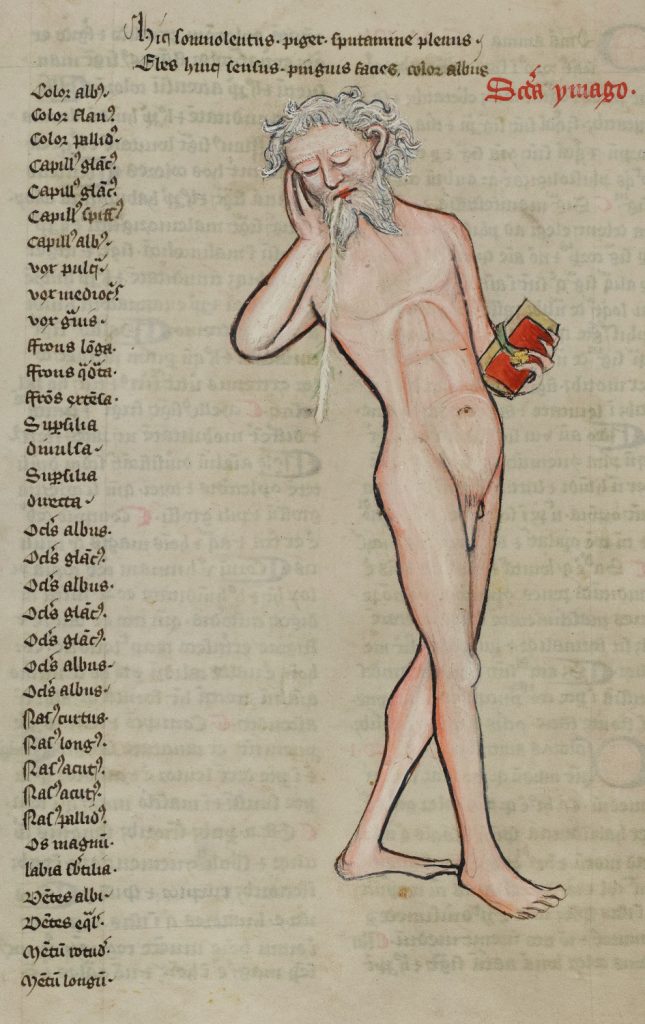

Personifications of ‘Sanguine’ and ‘Phlegmatic’, from the Liber cosmographiae of John of Foxton (Cambridge, Trinity College, MS R.15.21, ff. 12v and 13v, details)

Classical medical principles were key to the medieval understanding of the body and thus of the skin. Connected to the theory of the humours was the concept of ‘complexion’, the particular combination of phlegm, blood, black bile and yellow bile in a person’s body. This manifested not only in behavioural characteristics or temperament — the cheeriness of a sanguine person, or the irritability of someone choleric — but in outward appearance: for instance, according to verses on the humours from the Regimen sanitatis Salernitatis, a sanguine person is ruddy, a melancholic person sallow, the choleric dry and jaundiced, while their phlegmatic counterpart is plump of cheek but pale. Since illness was thought to be caused by imbalances in the humours, one’s complexion could be an indication of underlying disease.

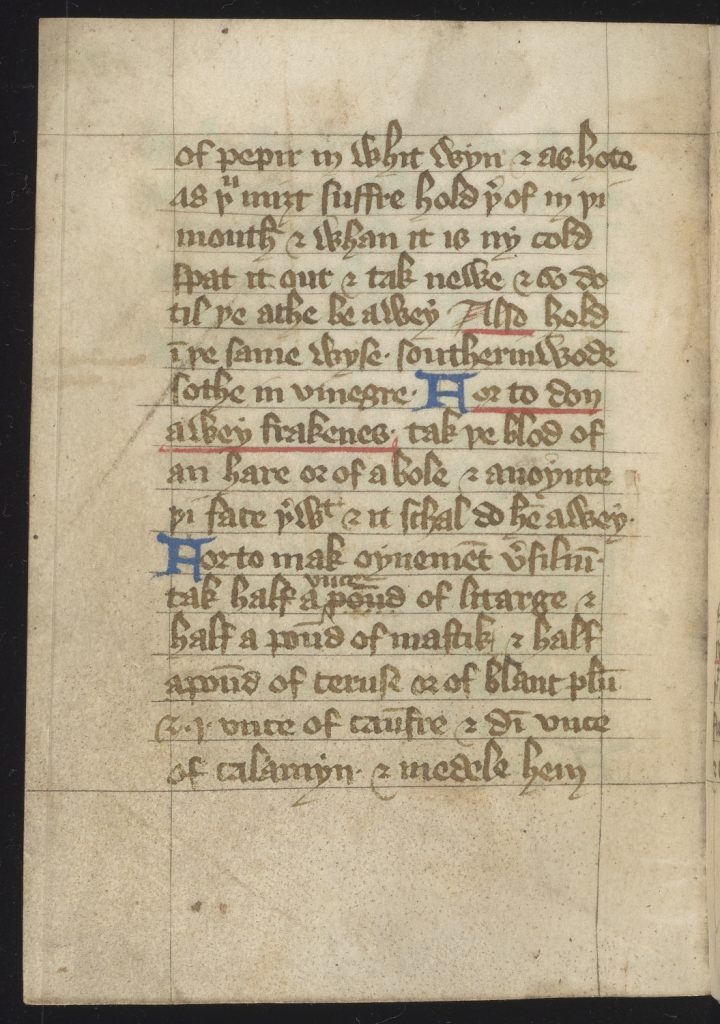

The manuscripts contain evidence of medieval people’s concerns about their appearance or its perception by others, shedding light on cosmetic standards of the period. In MS Add. 9308, for instance, there are instructions ‘For to don awey frakenes’ — how to get rid of freckles — which recommend anointing the face with hare’s or bull’s blood. Treatments for freckles, or ‘lentigines’ in Latin, appear in earlier medical texts such as the ‘Trotula’ compendium, which suggests creating a remedy from powdered bistort root, cuttlefish bones and frankincense.

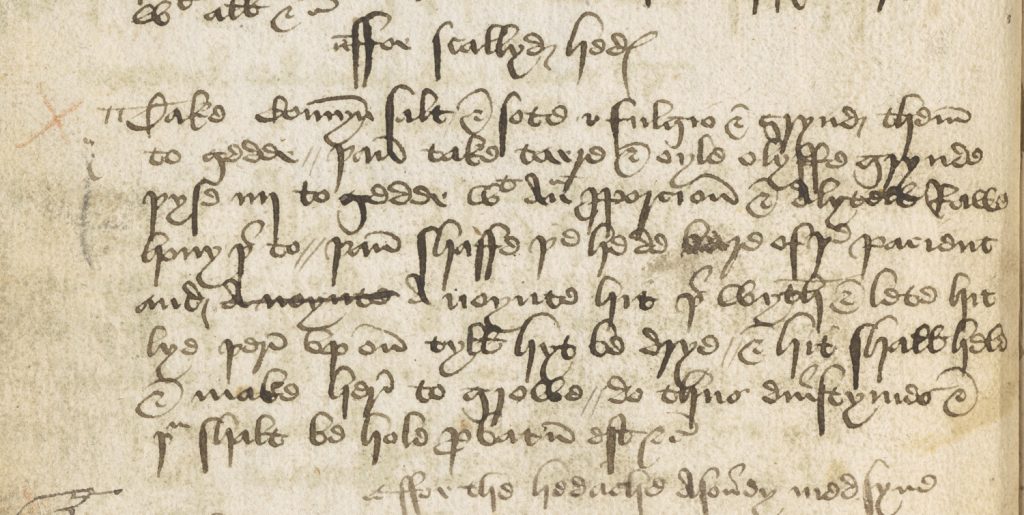

Further recipes in MS Add. 9308 focus on the skin’s appearance. A recipe to whiten the skin — ‘For to make þi face whyt’ — (f. 13v) combines ‘baru gres’ (pig fat) and ‘whit of an ey’ (egg white), which one should ‘staump […] to gedere with a litil powder of bayes’ (stamp together with a little powder of bay). Again, the face should be anointed with this concoction. Skin and hair treatments sometimes appear in conjunction, as with a remedy in MS Ee.1.15 (f. 8v) for ‘scallyd hedes’, a scaliness of the skin akin to dandruff. The head has to be shaved in order for the medicine to be rubbed on and left to dry, but the reader is told ‘hit shall hele and make here to growe’, suggesting there may have been both medical and aesthetic anxieties at play in the use of this treatment.

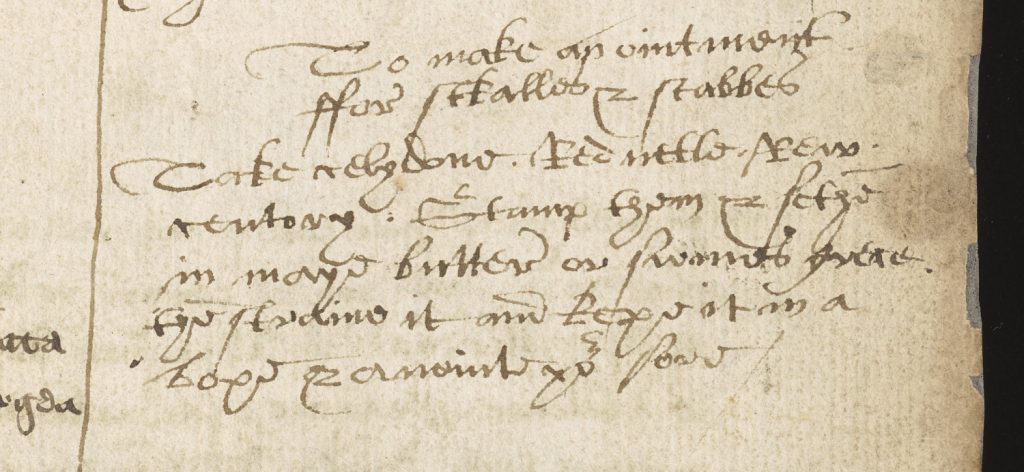

Whereas most of MS Add. 9308 has been copied by a single scribe, MS Ee.1.15 was compiled by many different hands that added recipes at various stages to the book. The first part of the manuscript was made in the second half of the 15th century, but continued to be supplemented in this way well into the 16th century. One of these later insertions is a recipe for an ‘ointment ffor scalles and scabbes’: ‘Take celydone. Red nettle. Rew. centory. Stamp them and sethen in maye buttere or swines grece then straine it and kepe it in a boxe and anointe your sore.’

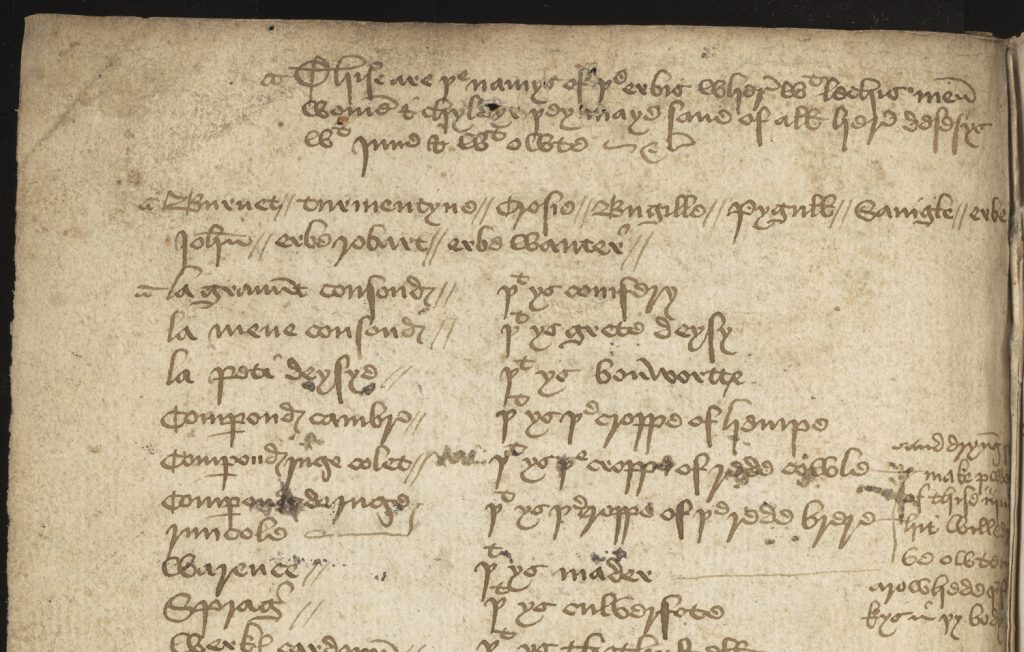

The recipe follows the usual conventions and structure of a medical cure: take these ingredients, do something to them, then apply in a certain way. It features common cultivated herbs and plants, and fats derived from domesticated animals: celandine, red nettle, rue, centaury, and a type of butter made in May or pig fat (again). Such ingredients recur regularly in medieval medical and cosmetic remedies; indeed, on f. 100v of this manuscript is a list of thirty-four herbs in Latin or French and their Middle English equivalents, under the title ‘the namys of þe erbis wherewith lechis men, women and chyldyr þey maye saue of alle here desesys withinne and withowte’ (i.e. the names of the herbs that leeches use to cure both internal and external ailments in men, women and children). Less common is the advice on storage — ‘straine it and kepe it in a boxe’ — and the phrasing at the end — ‘anointe your sore’ — which indicates its use on one’s own person as well as patients.

Such simple remedies are rarely accompanied by precise definitions of what kind of ‘scabbes’ or ‘scalles’ were of concern. They may have been the result of what we now describe as the process of ‘cicatrisation’, in which a dry crust of skin forms over a wound. However, we know from usage elsewhere that these terms carried broader meanings than the modern concept, and can refer to skin diseases more generally. At the least, the base of oil or fat in these recipes would have helped to moisturise and repair a dry, scaly or scabby skin condition.

Such ‘salves’ and ‘ointments’ reveal an interesting intersection between religious and medical practice. The word ointment is connected to the act of anointing, which we have seen mentioned above; there was even a practice of healing the sick by anointing them with blessed oils. These terms are etymologically linked to religious practice and belief and reflect contemporary ideas of salvation and healing — though of the body here, rather than the soul. The root of ‘salve’ is the Old English word ‘sealfian’, meaning ‘to anoint’, and the Latin verb ‘salvare’, ‘to save’, the same term used in relation to the curative potential of the herbal list mentioned above.

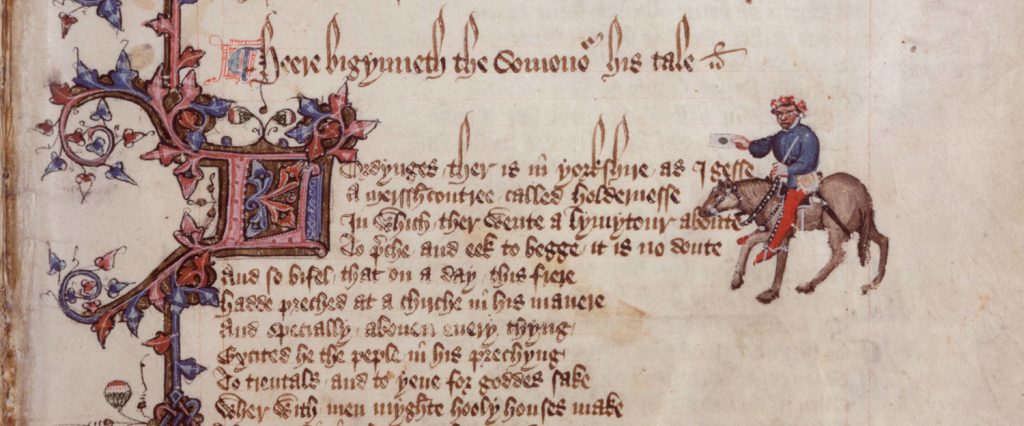

Alongside recognisable terms like scabs, less familiar conditions appear in MS Ee.1.15. The medieval term ‘saucefleme’ combines ‘salt’ and ‘phlegm’ and refers to an imbalance in the four humours. This illness manifested on the skin of one’s face in lumps, scabs, pustules and redness. Readers of the Canterbury Tales may have come across this term in the description in the General Prologue of Chaucer’s character the Summoner:

A Somonour was ther with us in that place

That hadde a fyr-reed cherubynnes face,

For saucefleem he was, with eyen narwe

As hoot he was and lecherous as a sparwe,

With scalled browes blake and piled berd.

Of his visage children were aferd.

Not only does the condition blemish the Summoner’s appearance, but it reflects his unpleasant character, and strikes fear into children who see his face.

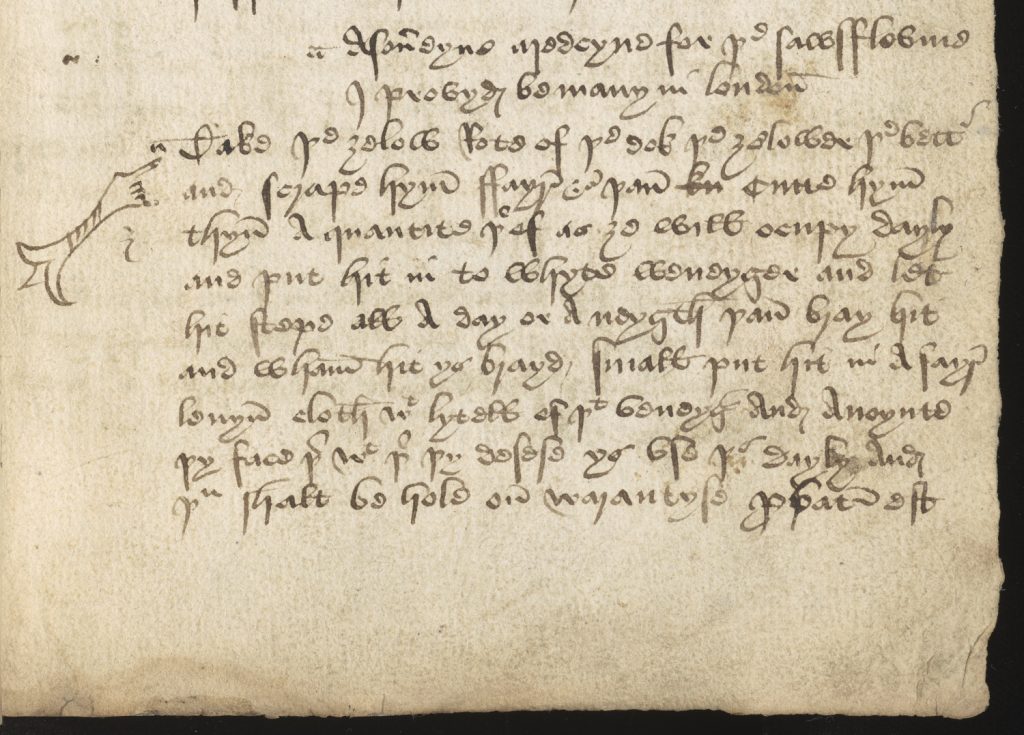

Understandably, a sufferer of saucefleme would desire relief not only from the physical symptoms and discomfort, but also from the social stigmatisation that it attracted as a consequence of its connection with a sinful nature. MS Ee.1.15 contains several remedies for this problem, among them one apparently with attested credentials: a ‘souerayne medcyne […] iprovyd be many in London’ (f. 97r). Dock root is the primary ingredient, ‘þe ȝelower þe bettur’ (the yellower the better). After peeling, chopping and steeping it in white vinegar, it is then ‘brayd’ (crushed). A little is added to a linen cloth, which was then used to anoint the face each day. A little hand or ‘maniculus’ in the margin points to the remedy, drawing the reader’s attention to a cure that is supposedly proven, and is guaranteed to work: ‘þu shalt be hole on warantyse probatum est’.

The manuscripts digitised as part of Curious cures offer fascinating insights into medieval medical treatment and practice. By exploring these manuscripts, we can better understand what ingredients were typical or commonly available, the conventions for recipe writing and preparation, and the conditions that were apparently most often of concern to patients and their healers. The presentation in these two examples shows that ideas of physical health and physical appearance were closely linked at this time, however much we might think of ‘medical’ and ‘cosmetic’ as separate matters: the former crucial to one’s health, the latter superficial. With meaning imbued in the appearance and health of the skin, it could furthermore be interpreted as mirroring a person’s characteristics and qualities. The ideal complexion reflected the ideal of both physical and spiritual health. With many manuscripts from the Curious Cures project to explore further, there is scope to learn much more about medical and cosmetic approaches to skin and complexion.

Thank you to the Curious Cures project team for the opportunity to write this blog and for their work on these wonderful manuscripts. Thank you also to my supervisor, Dr Shazia Jagot from the University of York, for her support last year with my dissertation project.

References and resources:

- The Green Middle Ages: The Depiction and Use of Plants in the Western World 600-1600, ed. by Claudine Chavannes-Mazel and Linda IJpelaar (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2023).

- Steven Connor, The Book of Skin (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004).

- The Trotula: An English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine, ed. by Monica H. Green (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

- Peter Murray Jones, ‘Herbs and the Medieval Surgeon’, in Health and Healing from the Medieval Garden, ed. by Peter Dendle and Alain Touwaide (Martlesham: Boydell & Brewer, 2015), 162–79.

- Julie Orlemanski, Symptomatic Subjects: Bodies, Medicine, and Causation in the Literature of Late Medieval England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019) <http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv16t6jgf> (accessed 10 August 2024).

- Carole Rawcliffe, ‘“Delectable Sightes and Fragrant Smelles”: Gardens and Health in Late Medieval and Early Modern England’, Garden History,36 (2008), 3-21.

- Carole Rawcliffe, Medicine and Society in Later Medieval England (Stroud: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1995).

- Edith Snook, ‘“The Beautifying Part of Physic”: Women’s Cosmetic Practices in Early Modern England’, Journal of Women’s History, 20 (2008), 10-33.

- Kathleen Walker-Meikle, ‘Animals: Their Use and Meaning in Medieval Medicine’, in A Cultural History of Medicine in the Middle Ages, vol. 2, edited by Iona McCleery (London, Bloomsbury Academic: 2023), 87-106.

- Reading Skin in Medieval Literature and Culture, ed. by Katie Walter(New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

Images reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge and the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.