True crime, whimsy and rhyme: newly-catalogued broadsides & slip-songs

This post is by Sofia Frattaroli, Library Assistant at Murray Edwards College Cambridge & current student on the Library & Information Science course at UCL. Sofia was a volunteer at the UL for seven months during 2025 and catalogued over eighty eighteenth- and nineteenth-century broadsides and slip-songs.

Between February and September, I volunteered in the Rare Books Reading Room, to gain cataloguing experience before beginning my studies in Library and Information Science at UCL. The project I was tasked with was to catalogue a large collection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century slip-songs and broadsides that had been at the UL for many years, but had not yet been catalogued.

Slip-songs and broadsides are cheap, ephemeral publications, often printed on a single sheet of thin paper. Survival rates are poor, despite the vast number printed at that time. Those that do survive are sometimes the only remaining copy of that title. They usually consisted of the printed lyrics of a popular song at the time, either from theatrical performances or sung at pleasure gardens, but sometimes they would also feature sensationalised accounts of crime and political statements. This definition is well-supported by the UL’s collection, which ranges from news announcements and religious hymns to nonsensical rhymes and crime, many of which you wouldn’t necessarily expect to find in the library. Although the collection is widely varied, I’ve chosen some examples that stood out and, in my opinion, broke the mould of what you would expect to find on nineteenth-century print in the UL.

True Crime

Slip-songs were an interesting way to relate news of crime during this period, telling the grisly stories through verse and poetry. Compare this to the news today – newspapers would simply print a news article laying out the sombre facts, interviewing witnesses or family members. These ‘murder-ballads’ made the accounts more sensational for the sake of entertainment, employing more dramatic language than the original article to captivate their audience. These were also a good way to relay the story in a smaller, more entertaining package than just reading a large block of informative text, and it helped disseminate information about real-life murders to the segments of society that lacked literary education. They made news accessible to a broad spectrum of society, and encouraged public discourse, while still maintaining a level of entertainment.

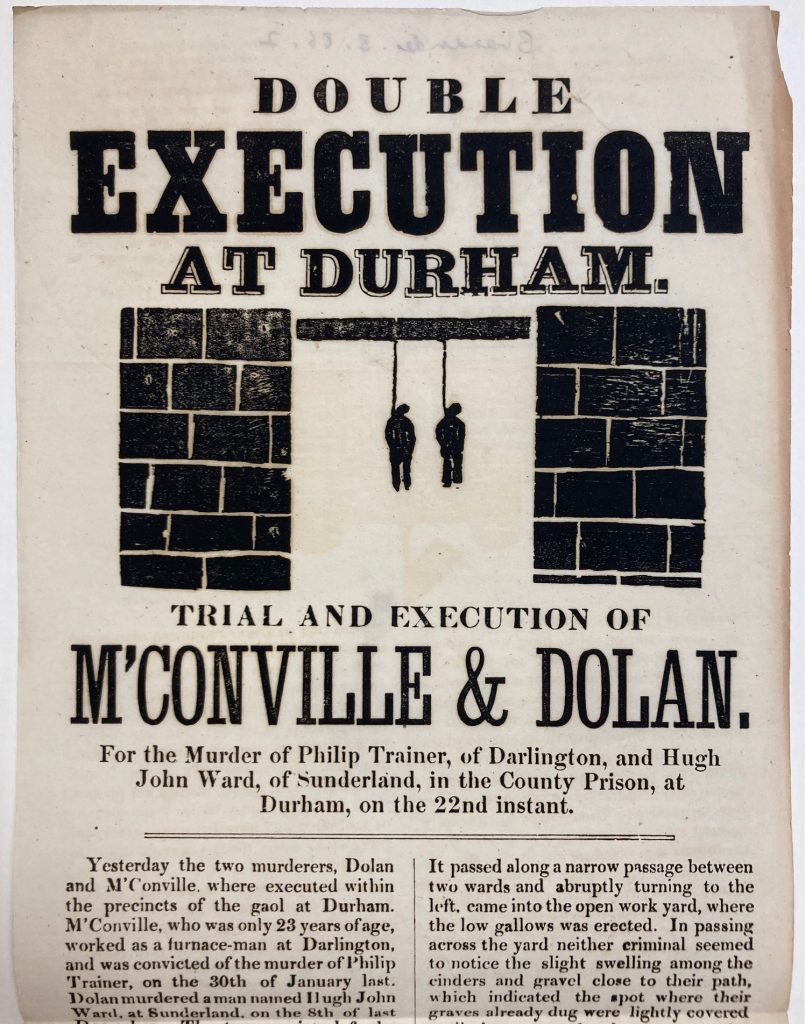

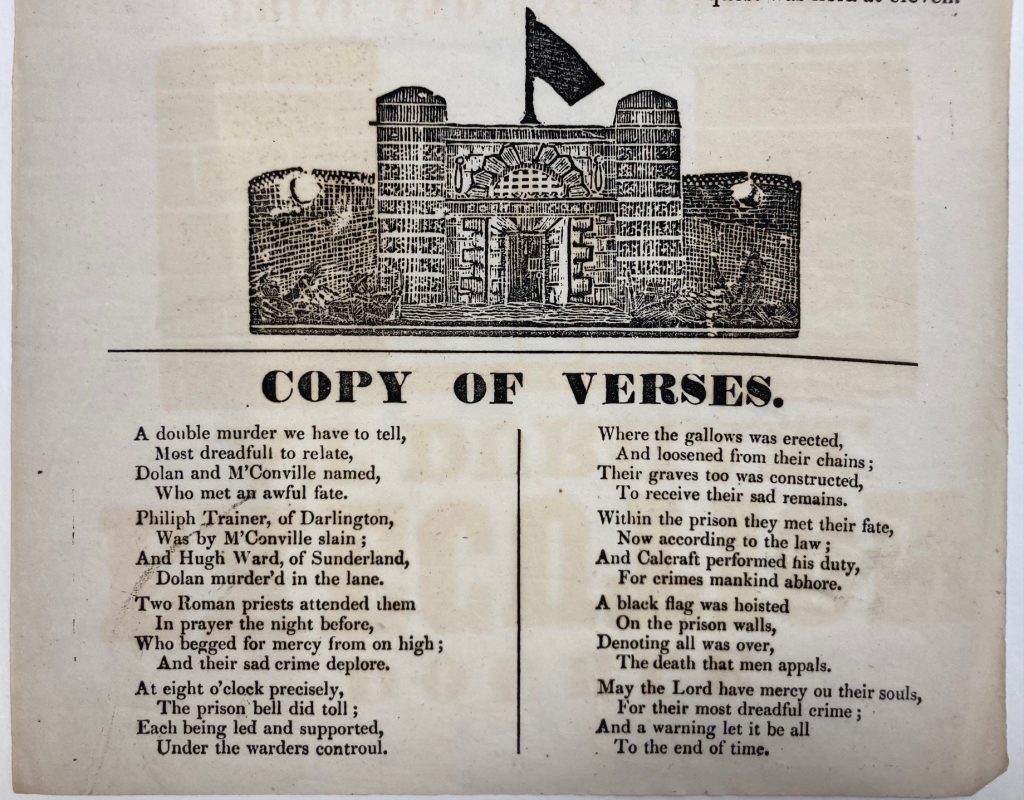

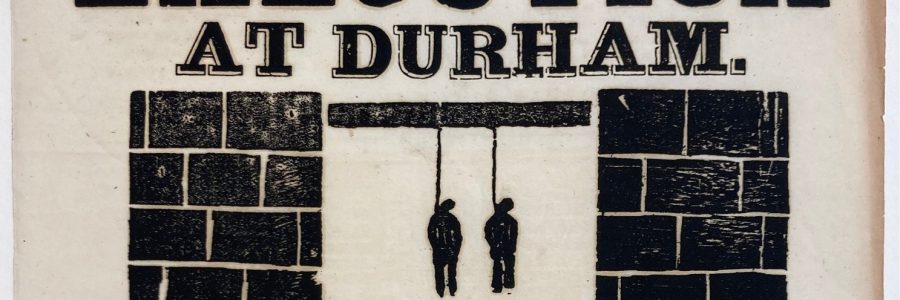

A prime example of true crime slip-songs is the “Double Execution at Durham”. This sheet details the trial and execution of John Dolan and John McConville at Durham Gaol on either the 22nd or 23rd March 1869. These executions were the first to take place in the North East following the implementation of the Capital Punishment Amendment Act in 1868, where all prisoners sentenced to death for murder had to be executed in the prison which they were held at.

This sheet has a length of 51cm, also the largest to be shown in this post, though it was not unusual for slip-songs to be long in height and narrow in width. Its height gives plentiful space for the event to be told in two methods – first in an article, and second as a set of rhyming verse. Both formats are separated by woodcut illustrations, depicting hanging figures and a prison, which immediately draw your eye. Out of the true crime examples, this event is the most documented, with plenty of context available regarding the crimes, the victims, and the executions, though its donor to the library is unidentified, and is the only catalogued copy as far as we can tell.

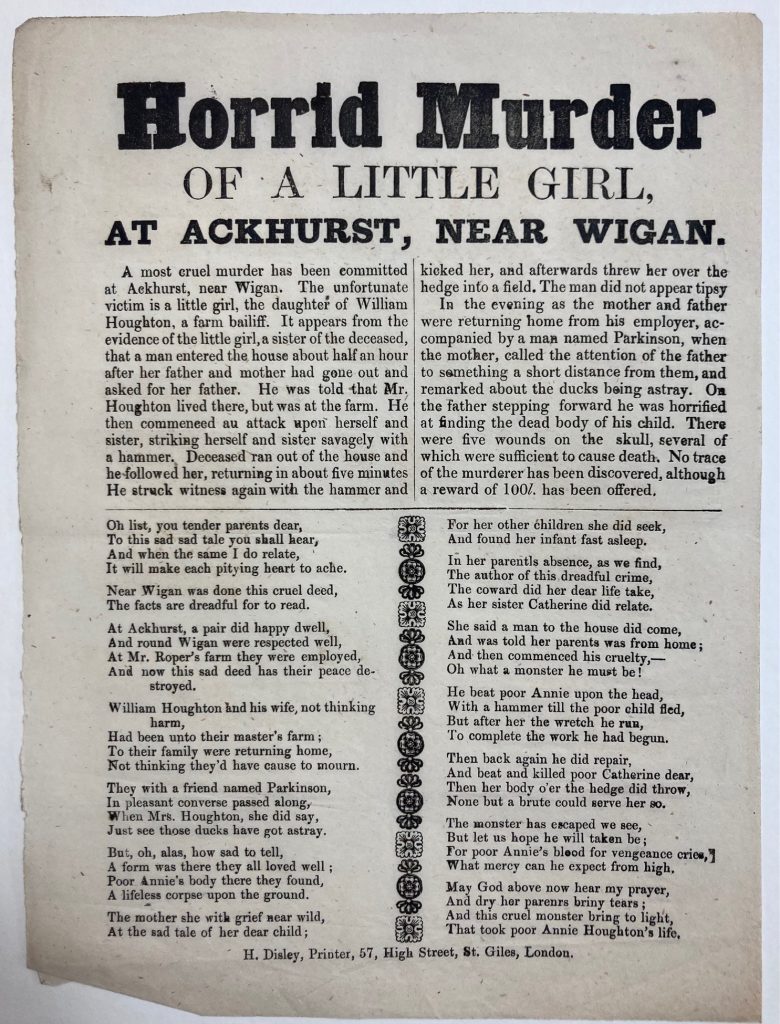

Another entry in the true crime genre is the “Horrid murder of a little girl”. It details the gruesome story of a twelve-year-old girl in Wigan in 1868; she was left by her parents to watch over the house while they ran an errand, at which point the murderer came to the door with a dog and chased the girl with a hammer, as her younger brothers slept upstairs. Her younger sister was the only witness, although she too was chased by the killer, but she managed to escape and hide until her parents returned.

There are some extant articles and documentation about the crime, with varying totals for rewards to those who could find the killer. However, documentation naming the killer and declaring his capture does not seem to exist – making this a cold case! Similarly to the Durham article, this tale is told both in article and verse format, separated with woodcut borders, and its donor is unknown. Only one other copy exists in the UK, at the University of East Anglia – the only other copy exists at the University of Illinois.

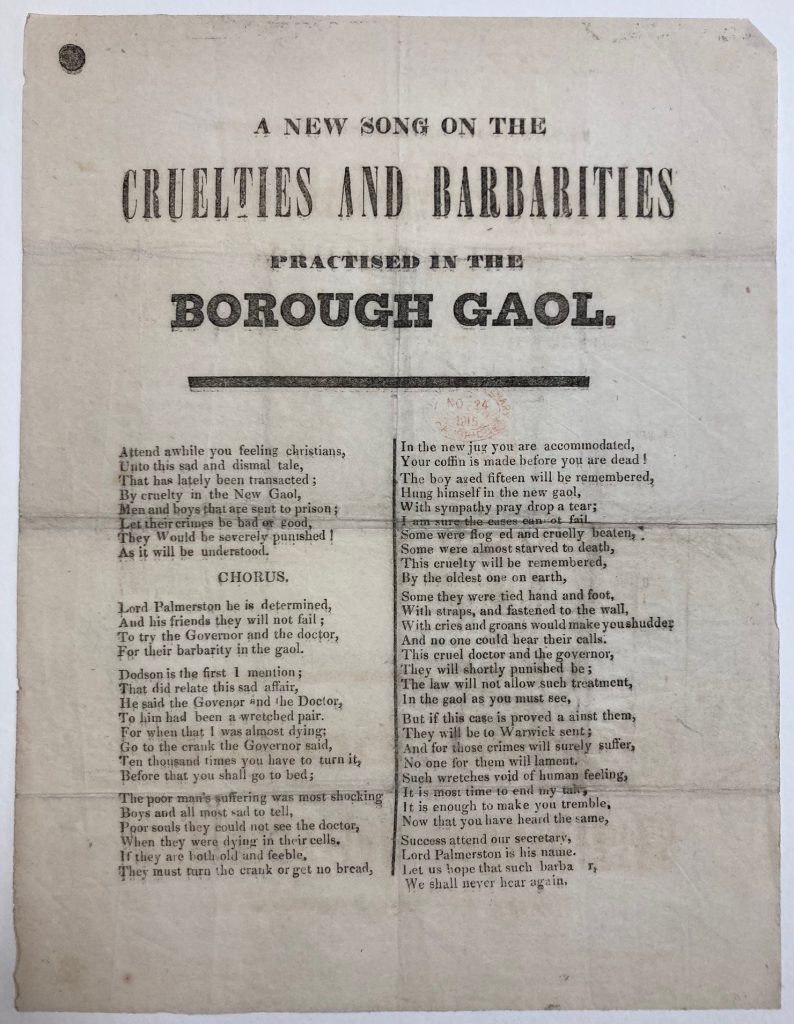

The third example here moves away from the gothic murder mystery trope, as it doesn’t focus on the crime of an individual, but the crime of the government. “A new song on the crimes and barbarities in the Borough Gaol” describes the cruel treatment of prisoners in this prison, who are recorded to be as young as fifteen, and committing suicide to escape their treatment. Borough Gaol in Birmingham was noted for its severe treatment of prisoners between 1831 and 1853, employing the crank as a form of manual labour and resulting in prisoner suicides. This was addressed by Lord Palmerston, when he opened a public enquiry in 1853, regarding the cruelties taking place. Different dates are recorded in extant documentation for the opening of this prison, but its history of abuse is longstanding.

This slip-song differs further from the above examples, showing no article of the events, and is structured more like a song, with a chorus break clearly indicated in the left column. Although there is no listed song to indicate the melody to the reader, the original audience would perhaps have known the tune intended for these lines. This particular sheet has been in the UL since 1915, but its donor has not been recorded, and is currently the only catalogued copy in the UK. This item reads more like a social commentary to the cruelties taking place at the prison rather than detailing the events of a recent crime or execution; slip-songs would employ tunes to create discourse on political characters and events, and critique any misgivings or wrongdoings (in this case, the poor treatment of prisoners in Borough Gaol).

Nonsense and whimsy

It must be noted that slip-songs were not always serious and solemn publications, even when employing the use of rhyme and verse. There were many humorous and silly publications floating about, featuring absurd situations, illogical wordplay and nonsensical rhymes. In the stresses of nineteenth-century England, these publications were sure to provide a form of escapism and bring a little light into the readers’ lives, even if only for a quick laugh. Publishing sheets such as these, lacking in any real truth or substance, demonstrates society’s desire to shock and entertain.

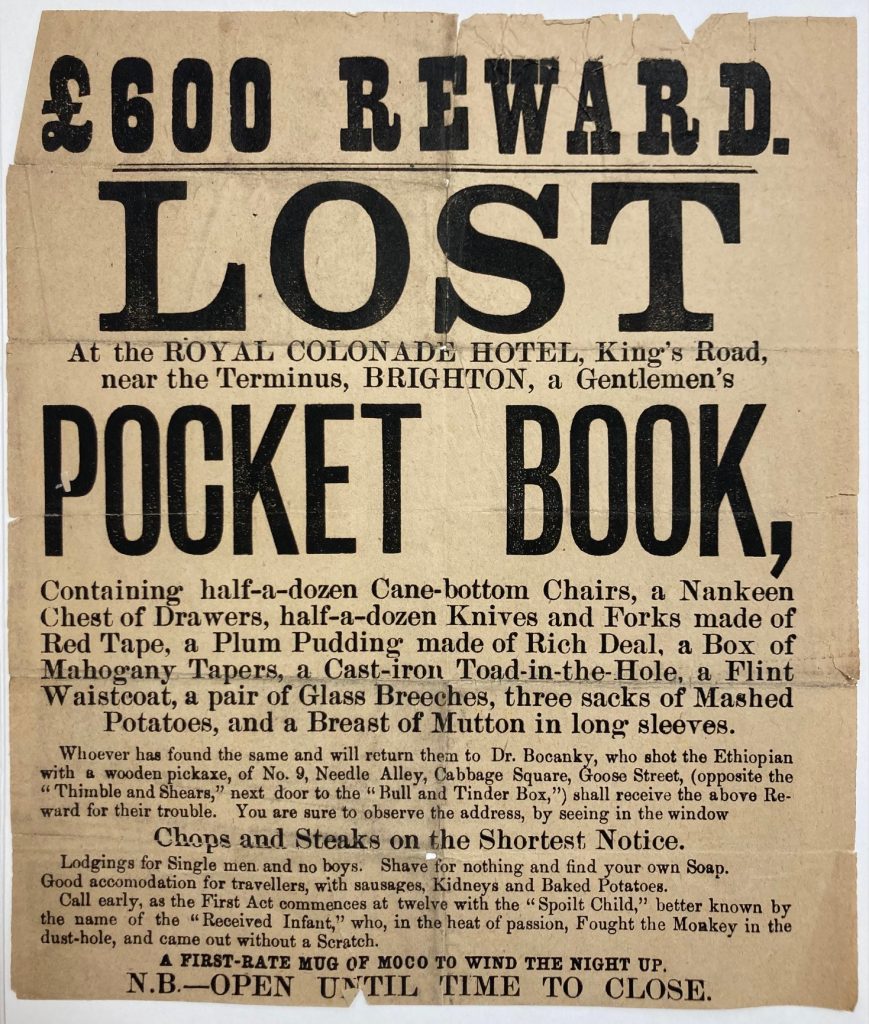

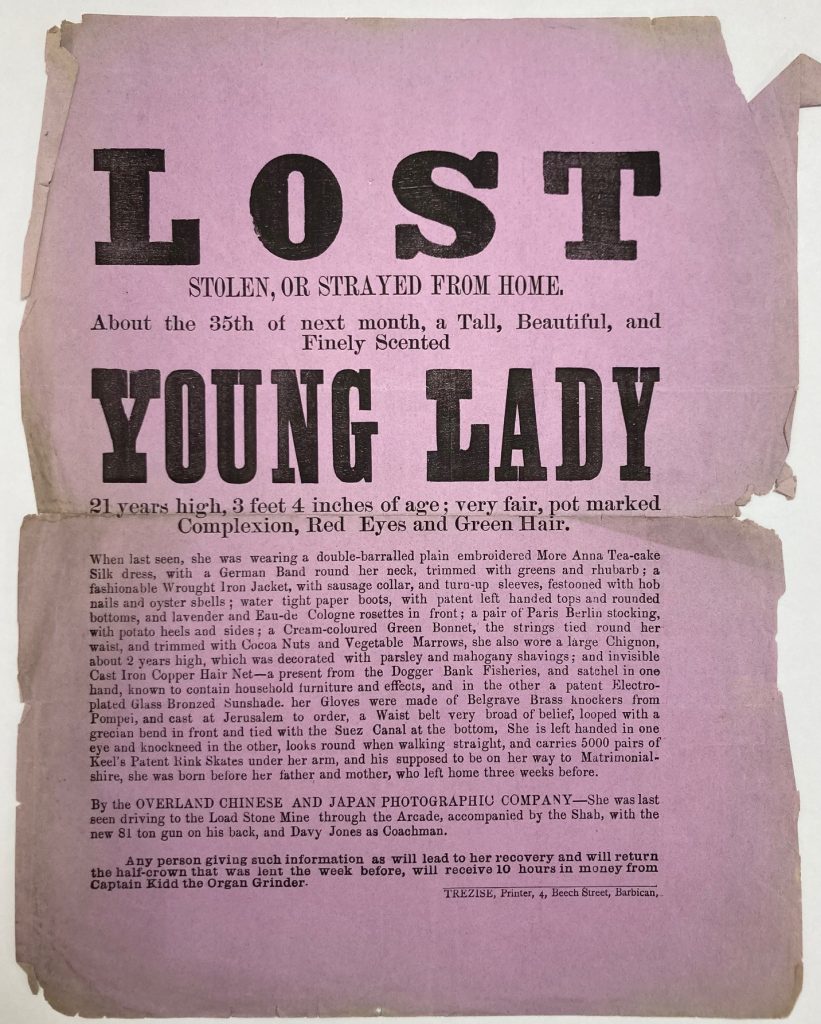

A pair that define themselves as truly silly in my view, are the “Lost Pocket Book” and a “Lost Young Lady”, respectively. These sheets were part of a donation by Professor Edward Meryon Wilson (1906-77), Professor of Spanish at the University between 1953 and 1973. An interesting detour from the Professor’s daily teachings, these two items display a sense of humour, as well as his niche collecting habits! Although a donation date has not been given, we could assume that they are part of a large bequest of broadsheets given to the UL upon Wilson’s death, part of which has previously been catalogued and given a spotlight here.

Both sheets have not been signed by an author, and only “Lost Young Lady” has a publication imprint – although, sadly this does not tell us much, as this sheet is the only catalogued document from the address given. It is fair to assume that these both may come from the same publisher, as they both read similarly and have similar elements between them. The truly captivating element of these two sheets, however, is that from first glance they both look like regular ‘missing’ adverts, but once you begin to read the words, they stray further and further into nonsense! The reward for the lost pocket book is £600, which is the equivalent of £43,000 today; and the reward for the lost young lady is “10 hours in money from Captain Kidd the Organ Grinder”.

What I really enjoy about these sheets is that they are both ‘word waffle’, rather than poetry, and an excellent parody of potential missing items/persons adverts of the day. There was a trend for advertisers to place fake ads to capture the public’s attention or critique the practices of other advertisers – these slips could be reactionary to a then-recent lost advert, or to several at once, and the author is taking a swing at them by writing silly lines to be disseminated on a cheap publication. Adverts such as these highlighted the absurdity of items being lost or sought, and exaggerated the perceived oddity or desperation of those placing the ads in the first place. The absurd descriptions and exaggerated language makes the ordeal seem ridiculous, getting a rise out of the general public. Given the meteoric rise in publication print at the time, lost and found adverts became a common type of advertisement, particularly for objects such as notebooks – further demonstrating the slip-songs now in UL custody are satirical works with the aim of mocking such commonplace adverts.

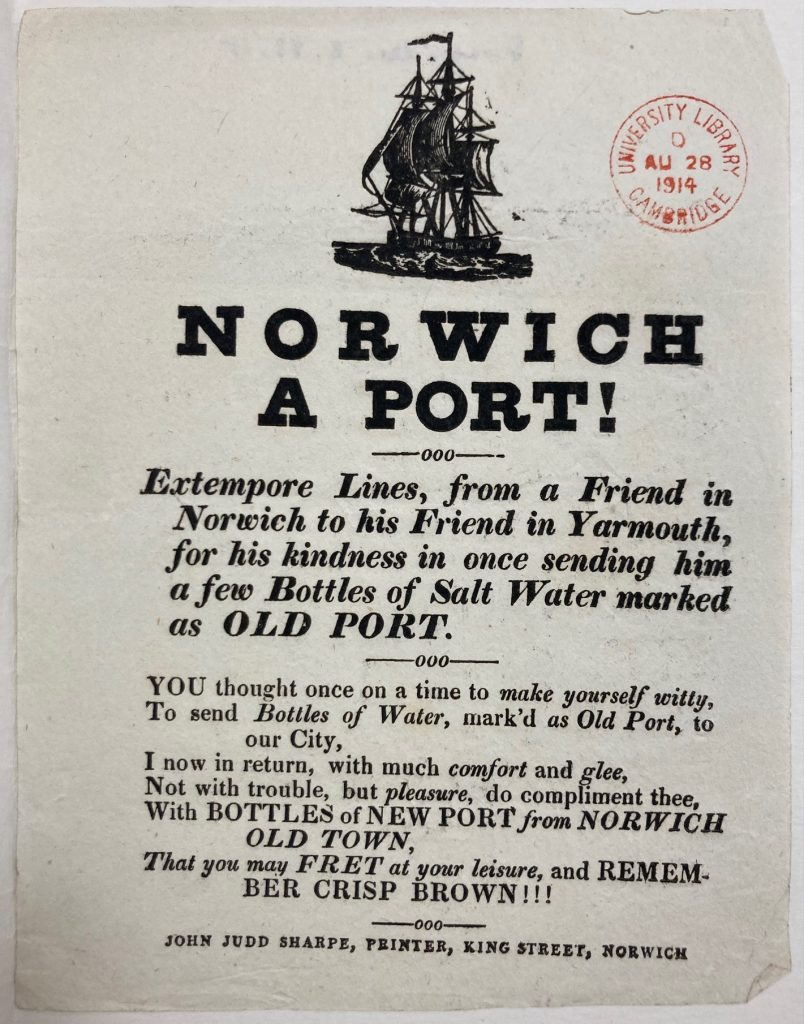

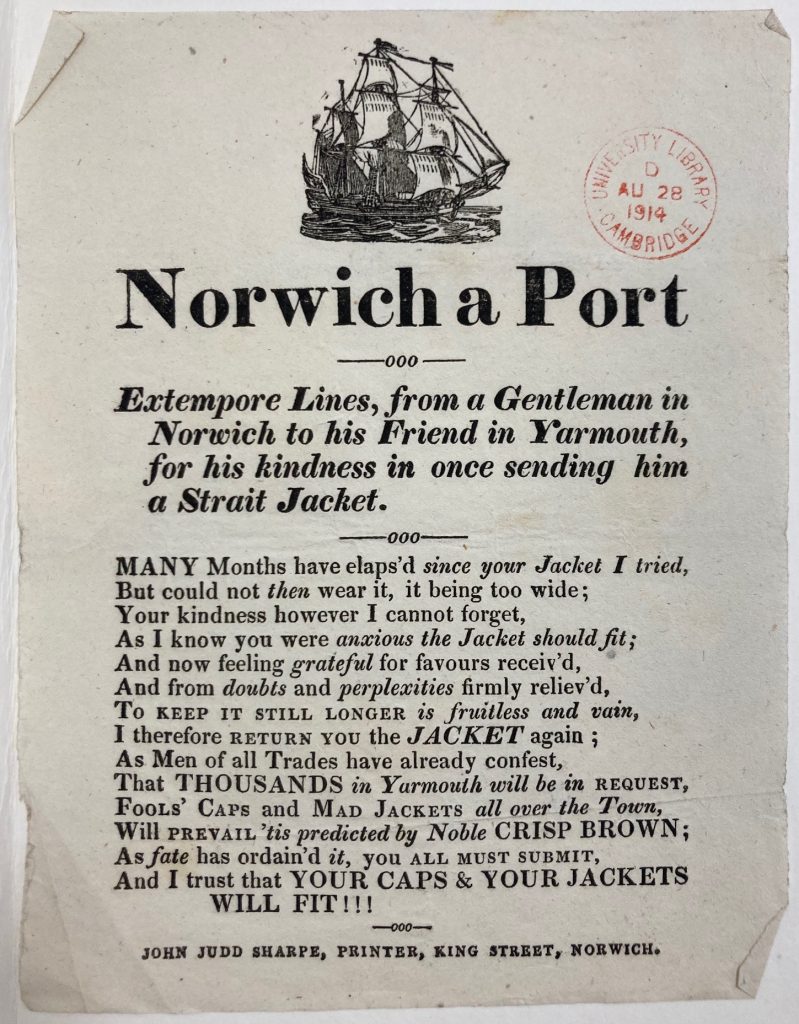

The final pair in this category is Broadsides.B.83.15 and Broadsides.B.83.16, both of which are titled “Norwich a Port!”. Both sheets were donated by Mrs. A. J. Edmond, on the 28th August 1914. Although we are unsure who the donor was in relation to the Library, her name has cropped up again and again during my time on this project, and has significantly contributed to the collection of broadsides and slip-songs.

These sheets are both written as extempore lines, which means written without any thought or preparation, as improvised poetry. These are both short comedic verses consisting of rhyming couplets, where the author is supposedly receiving strange gifts such as a strait jacket and a bottle of salt water labelled as port! There is no way to know if this actually happened or if it was written for comedic effect; either way, it is a great demonstration of local humour in the nineteenth century.

The author is not specifically named, but only referred to as “a gentleman in Norwich to his friend in Yarmouth”; they are almost certainly written by the same person. It begs the question; were there any responses from the aforementioned friend in Yarmouth, and do they still exist today? Although the specific identity of the author is unknown, the publication imprint is consistent – both were printed by John Judd Sharpe, a printer and estate agent in Norwich. (Fun fact: he was also a licensee for a couple of pubs in the area during his lifetime!). Though the date of publication is not stated in the imprint, other extant publications by Sharpe indicate these two sheets were printed somewhere around the 1830s.

All the slip-songs and broadsides catalogued by Sofia during 2025 are now in the Library’s iDiscover catalogue, and may be ordered to the Rare Books Room.