Landbeach to Linnaeus: a guest post by Jaap Harskamp

Cambridge University Library holds a rich collection of botanical studies printed in the Low Countries, many of which were originally part of the collection of the Department of Plant Sciences at the University. One outstanding work is Linnaeus’ Hortus Cliffortianus, of which two copies are held at the Library (CCF.47.13 & MA.40.26). The copy from the Department of Plant Sciences (CCF.47.13) has the bookplate of the Cambridge Botanical Museum (dated October 1888). The Hortus Cliffortianus is a catalogue of the plants in the garden and herbarium of George Clifford (1685–1760), whose family originated from Landbeach, near Cambridge. The book in folio, containing 36 plates, an impressive engraved frontispiece, and an accurate index, was sponsored by Clifford and printed in a limited edition by the author as presentation copies for fellow researchers within the plant exchange network (Hermann Boerhaave and Adriaan van Royen were the first to receive copies). This feature explores the Anglo-Dutch connections at the heart of one of the finest examples of botanical printing.

George Clifford III was a wealthy Amsterdam banker and one of the directors of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was known for his keen interest in plants and gardens. His estate the Hartekamp had a rich variety of plants and he engaged the Swedish naturalist Linnaeus (latinized name of Carl von Linné), who stayed there from 1736 to 1738, to write the Hortus Cliffortianus, a masterpiece of early botanical literature. Many specimens from Clifford’s garden were also studied by Linnaeus for his two-volume Species plantarum (1753), a work that laid the foundation for scientific plant nomenclature as we know it today.

The Clifford dynasty originated from East Anglia. The first recorded member of the family was Richard Clifford, who studied at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, which at the time was an important institution for the training of Anglican clergy. In 1569 he was appointed rector of Landbeach, a fen-edge village near Ely, just north of Cambridge (beach most likely means ‘shore’ here: both Landbeach and nearby Waterbeach were at one time situated at the edge of The Wash). Henry Clifford was born in Landbeach and like his father he studied at Corpus Christi. He named his son George and sometime between 1634 and 1640 George Clifford I moved to Amsterdam and lived the rest of his life on the Zeedijk. Six of his children were baptized in Amsterdam’s historical Presbyterian Church at the Begijnhof, and two in the Oude Kerk. He established the family business in the city and, in 1664, is recorded as owning a sugar plantation in Barbados.

George Clifford II was born in 1657. He continued in the trade his father had started. Business prospered and, in 1709, he was able to buy the Hartekamp (for the substantial amount of 22,000 guilders), an estate with a formal garden and conservatory in Heemstede, just outside Bennebroek, near to the coastal dunes and close to the famous Dutch bulb fields. The original house had been built in 1693 by Johan Hinlopen, who had been in charge of running the lucrative postal route between Amsterdam and Antwerp. Hinlopen designed the basic garden and built the orangery. His grandfather had been of Flemish origin, one of the countless cosmopolitan merchants who left Antwerp after the Spanish suppression of the city. A trader in cloth and Indian ware he was a co-founder of the Dutch East India Company in 1602. His son Jan Jacobszoon expanded the business and became an important art collector and supporter of Rembrandt, Gabriel Metsu, and others.

George Clifford III was born in 1685 into what had become an extremely wealthy Anglo-Dutch merchant dynasty. The family business entered banking at the start of the eighteenth century and established an international reputation lending money to royalty, the Vatican, and the English and Danish governments. George III also was a Governor of the Dutch East India Company (but not, as is often stated, at any time Burgomaster of Amsterdam) and a keen botanist. On the Hartekamp he accumulated a famous living and dried plant collection and gave the garden its international reputation, acquiring specimens of new species from all over the world. He acted as patron of the young Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus, whom he employed in the double capacity of hortulanus (supervisor) of his collection and physician (the master of the house was somewhat of a hypochondriac).

Linnaeus had been introduced to Clifford by Johannes Burman, Director of the Amsterdam Botanic Garden and Professor of Botany, who supplied tropical plants to the Clifford collection through his close connections with the East India Company. Linnaeus named after him the Burmannia, a family of chiefly tropical herbs with basal leaves and small flowers. The meeting between the two men turned out well for both of them. Linnaeus was overwhelmed by the botanical riches of the gardens and in particular by the ‘houses of Adonis’ (hothouses) where he encountered a bewildering variety of plants from Southern Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas. Clifford on the other hand was impressed by Linnaeus’ effortless ability to classify plants that were new to him. Clifford offered Linnaeus free board and lodging, and a financial allowance of one ducat a day, or 1,000 florins per annum. The young botanist was overjoyed. By the time he took up his employment in 1735 the estate contained, in addition to the garden, a large collection of animals, an orangery and four heated greenhouses. Through the activities of eminent botanists such as Herman Boerhaave, Adriaan van Royen and others, many exotic plants were added to Clifford’s collection and dried plants were exchanged as herbarium sheets. International cooperation between collectors and scientists contributed to the rapid development of plant systematics both in terms of taxonomy and of practical knowledge of the world’s botanical wealth and variety.

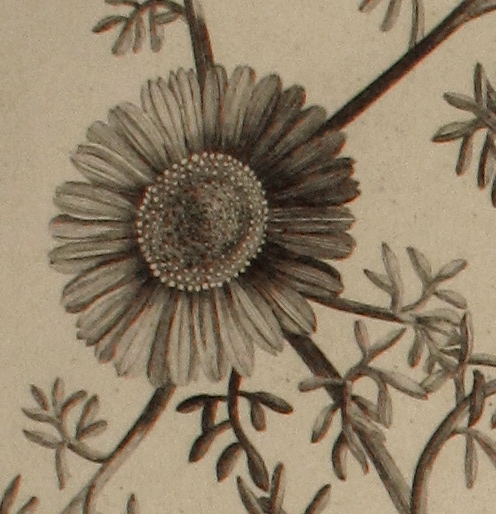

Turnera, a genus of plants belonging to the passionflower family and named after English naturalist William Turner (1508-1568). Hortus Cliffortianus, plate X (detail)

The herbarium played an important role in the development of scientific botany. The preparation of herbarium specimens goes far back to the Egyptians, but the systematic technique for keeping plants as dried reference specimens began in Tuscany during the sixteenth century. Luca Ghini, founder of the first botanical garden in the world at Pisa, introduced this method to his students at the University of Bologna. Initially herbaria were bound together to form books, such as that of the apothecary Petrus Cadé, the oldest herbarium known in the Low Countries. In the eighteenth century botanists started to keep the individual herbarium sheets separate which allowed rearrangement according to developing systematic ideas. Thus it became possible to lend individual herbarium sheets and exchange duplicates. Because of such exchanges it was no longer immediately clear who the owner of a particular specimen actually was. This is perhaps the reason—apart from mere aesthetics—why ornamentations such as pots, medallions, pennants, or cartouches were printed onto the sheets and thus acted as a kind of ex libris for the owner. This tradition is of Dutch origin and dates back to the 1720s; it had gone out of fashion by the end of the century. Clifford’s herbarium consists of 3,461 sheets. Many of the specimens are mounted in such a manner that they appear to be growing out of engraved paper urns and are held down by ribbons, with their names inscribed on ornate labels. In 1791, Clifford’s herbarium was acquired by the botanist Joseph Banks, Director of Kew’s Royal Botanic Gardens and President of the Royal Society of London, at the sale of the collections. It is now part of the collections of the Natural History Museum.

At the time of Linnaeus’ inventory, the garden at Hartekamp had 1,251 living plant species in the greenhouses, gardens and woods. Linnaeus catalogued the family’s complete collection of plants, herbarium and library for the Hortus Cliffortianus, and compiled his work with astonishing speed. It took him only nine months to prepare the manuscript. Until this time the individual herbarium sheets owned by Clifford were arranged according to the system applied by Boerhaave in his Index alter plantarum. Linnaeus ranked the plant species according to a sexual system which he himself had designed, based on the number and shape of both male and female reproductive parts. Within this system every species is placed in a genus and given its own unique Latin adjective. The Hortus Cliffortianus formed the basis for all of Linnaeus’ subsequent work. Many of his plant descriptions are repeated in the Species plantarum which appeared some fifteen year later. In this book Linnaeus introduced the consistent use of the binomial nomenclatural system with a genus name and a species epithet. The many samples taken from the Clifford collection were type specimens for Linnaeus’ new systematic ordering.

Frontispiece to Hortus Cliffortianus (detail), showing a young Apollo with Linnaeus’ features bringing light into the darkness (of ignorance)

Linnaeus collaborated with an outstanding botanical artist. In 1735 German painter and draughtsman George Ehret had travelled to England with glowing letters of introduction to patrons including Hans Sloane and Philip Miller, curator of the Chelsea Physic Garden. In the spring of 1736 Ehret spent three months in the Netherlands and stayed for several weeks at the Hartekamp where he made the majority of the illustrations. He then returned to England to settle in Chelsea, from where he sent the remainder of the illustrations. His efforts proved indispensable for the rapid dissemination of the underlying concepts of Linnaeus’ new systematic ordering. Through his famous illustrations, Ehret made Linnaeus’ new system more intelligible. Ehretia, a genus of flowering plants in the borage family (Boraginaceae—containing some fifty species) was named in his honour. Ehret’s plates served as the basis for the etchings of Jan Wandelaar who made the final prints for the book. The latter also produced the outstanding baroque frontispiece, the symbolism of which includes a young Apollo with Linnaeus’ features who brings light into the darkness (of ignorance).

In 1760 Pieter Clifford, the oldest son of George, inherited the Hartekamp, but he lacked his father’s passion for plants and the importance of the garden declined. After his death the estate was auctioned on 2 June 1788, probably due to financial problems relating to the bankruptcy of the Clifford Bank in 1772. It was the final chapter in what had been a grand Anglo-Dutch-Swedish undertaking in which natural beauty, science and art had been harmoniously merged.

Jaap Harskamp

Dr Harskamp is currently working on a project to report Cambridge University Library’s holdings of early printed Dutch books to the Short Title Catalogue Netherlands (STCN). 5,221 titles have been reported to the STCN to date, of which 637 are unique. For further information, see http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/deptserv/rarebooks/stcn.html.

Further reading

Blunt, Wilfrid. Linnaeus: the complete naturalist /introduction by William T. Stearn. London: Frances Lincoln, 2004. (See pp. 102–14; ch. 5)

Linnaeus, Carl. Clifford’s banana plant / translated into English by Stephen Freer; with an introduction by Staffan Müller-Wille. Ruggell: Gantner Verlag, 2007. (‘Regnum vegetabile’, vol. 148)

Linnean Society. All correspondence from Clifford to Linnaeus. http://correspondence.linnean-online.org

Natural History Museum. The George Clifford herbarium. http://www.nhm.ac.uk

Rutgers, Jorieke. ‘Linnaeus in the Netherlands’. Tijdschrift voor Skandinavistiek, 29/1 & 2 (2008), 103–16.

Uppsala Universitet. Linné on line. http://www.linnaeus.uu.se

A member of the CUL let me know about this excellent piece shortly after I had composed one of my own, on a trip to Clifford’s former estate at Hartekamp, as a blog for the Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Quite a coincidence! http://blog.kb.nl/harold-cook/linnaeuss-dutch-legacy

Thanks for letting us know about your own post on this. It’s great to see the image of the bust of Linnaeus at the Hartekamp estate!