The Zoologist’s Wartime Christmas

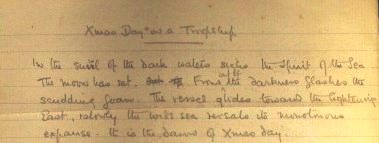

“In the swirl of the dark waters sighs the Spirit of the Sea. The moon has set. From out of the darkness flashes the scudding foam. The vessel glides towards the lightening East, slowly the wide sea reveals its monotonous expanse. It is the dawn of Xmas day.”

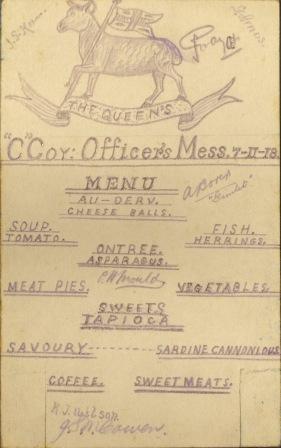

So begins zoologist Sir James Gray’s reflections on Christmas Day, 1917. Gray was 27 at the time, already known for his work in cytology (cell biology) and experimental zoology. During World War I Gray served as Lieutenant and later acting Captain in the Queen’s Royal West Surrey regiment. On Christmas Day, 1917, Gray was aboard a troopship headed for France. Gray’s outlook was bleak, but he retained his wonder at the natural world:

“In varied shades of yellow and of gold the clouds herald the rising sun. The waves reflect the morning light …. Padres hold their services, and the old old hymns of childhood float out over the sea. But over all is the mantle of Loneliness. Over all triumphs the spirit of the ocean’s solitude.

“The day wears on. The sun rides into a blue and almost cloudless sky. As other days and yet not the same. ‘There hath passed away a glory from the Earth.’

“Something is lacking, something the children know. A touch, and the eyes would sparkle; a word and the life would proclaim the gladness of the soul. Yet – everywhere the far off look, the vacant spaces, the sea.

“Peace on earth and goodwill toward men: but the Sword is drawn, and we are banished from our Home and from our Joy …. Veiled in clouds the sun sinks slowly in his glory. A gentle breeze blows from the South. Ceaseless the swirl of the waves, and infinite the waste of the waters.

“Here on the lonely sea Nature calls in Power to her evening children. Not in fierce anger, but in Solitude and Sorrow. When will we listen, when will her voice be heard?

“The evening star shines in the West: in the breeze is the whisper of Eternal Peace. Give us eyes to see – give us hearts to praise the Universal Good.”

Gray wrote this reflection on two sides of a small, loose-leaf sheet. He also made a more standard entry in his diary on the same day, echoing the similar sentiments, but in a darker tone: “A beautiful dawn – but thoughts depress one all day. ‘No Peace on Earth, and no Goodwill’ – it’s hard even to feel goodwill.”

Gray rarely wrote about his personal feelings in his diary, limiting himself mainly to practical notes about marches, the local environment, and notable occasions such as dinner with high-ranking military personal, or a shelling on his camp. Ever the zoologist, Gray kept copious notes about the fauna, flora, and culture of the places he was stationed, including parts of Palestine and Egypt. He made rudimentary drawings of remarkable birds and pressed leaves or fronds of local foliage between the pages of the diary. Gray recorded the violence of the war and occurrences of natural beauty side by side:

Friday 3 May 1918

Q31 A.

Watched a battery shell Turkish positions with aeroplane spotting. Glorious weather – into the ground a carpet of wild flowers.

A few months after his Christmas at sea, Gray received a letter from his friend Thomas (MS Add.8125/A.5). The letter makes clear Thomas’s regard for Gray, and also how distant Thomas’s presumably rather cushioned life was from the daily grind in the military.

Dated the 17th of January, 1918

Embossing on stationary reads: 49, Warwick Square, S.W.

My dear James,

I was delighted to get your letter and have been waiting to answer it in hopes of getting an address slightly more definite than R.E.F!

I admired your strength of mind in searching out the hiways of (?) Marseilles. Now listen to a plan I have been forming. The first holiday that we get after the war you and I will go and buy a donkey and a coster cart. Then we will fill the cart with a little tent and cooking things and pedlar’s wares, principally a tin plate canna[?], slip[?] made of shells, picture post-cards, regimental badges, tape, buttons, domes of silence1, cloth sausages to go under doors, cigarettes and such like.

We will start our tour in the Cotswolds, or possibly from Exeter, in which case we should work up through Somerset and Dorset.

If we found we had the pedlar’s instinct we would go and do the same abroad for a year afterwards.

The alternative is that we should keep a tobacconist’s shop in the shires with a little back-room where the more amusing customers could drink black coffee. The trouble about that is that it would be a long time before we could work up any custom. You could amuse yourself by drawing graphs of our deficit!

Wright has reverted to Captain and Lionel Charles and Maurice Kelly are just going on the staff! God help the fighting soldier.

Yours Ever,

Thomas [A.?] Patient[?] [Thomas-a-Patient?]

Nothing ever came of the plan – after the war ended, Gray launched straight into a successful career in academia.

Sir James Gray’s papers can be viewed in the Manuscripts Reading Room (MS Add.8125)

Notes

Back to Post. 1 What, you ask, are “domes of silence”? Domes of Silence were the name of rounded ends that were attached to the bottoms of furniture legs. They allowed heavy pieces of furniture to be moved with making a racket and scratching the floor. A nice description of domes of silence (combined with a rather ugly Anti-Semitic passage) can be found in a chapter by same name in the American novel The Mystery Mind (published in 1919) ( The_Mystery_Mind )