The Trial of Jerry McGill

Fragments of history frequently emerge out of the collections kept in the Manuscripts Reading Room. While cataloguing the GE Moore collection, I stumbled across this tale of McCarthyism in New York City. The following has been reconstructed from several letters written by the psychologist and philosopher VJ (Jerry) McGill to GE Moore’s wife, Dorothy Moore.

On the fifteenth of October 1954 Hurricane Hazel tore through New York City, downing power lines and felling trees. But even before the hurricane swept his city, Professor Jerry McGill had been experiencing upheaval and chaos. McGill, a 57-year-old professor of psychology, had been suspended from his job without pay for most of the preceding year and endured ‘six months of threats and pressure of unbelievable intensity to give names’ by a McCarthyist group, the Special Committee of the Board of Higher Education.

This was during a period of escalation in the Cold War, at the height of American paranoia about Soviet spies, and McGill had the misfortune of being a former member of the Communist Party (1936 to 1941). Despite having renounced Communism and allowing his membership to lapse, the Special Committee insisted McGill must still be involved with the Communist Party, and demanded McGill provide names of other members.

The stakes were high. As well as suspension of his pay during the trial, McGill faced possible dismissal from his job as associate professor at Hunter College. If dismissed, McGill would be considered an unemployable liability to other American universities.

No longer a believer in Communist doctrine, McGill ‘agreed to supply any facts about [him]self, and to cooperate in any way except to give the names of people who had been members long ago.’ He provided detailed accounts of the ‘past activities of the Communist unit at the College … if only to show that there had been nothing subversive about it,’ as well as two long written statements about ‘the party as [he] knew it between ’36 and ’41.’ Following the request of the chief council of the Special Committee McGill ‘persuade[d] two former members to testify voluntarily.’

McGill writes that, ‘The facts thus volunteered were used against me in the trial. The statements themselves … were not admitted into evidence.’

The two former members of the Communist Party who McGill had known testified that McGill had renounced his membership in 1941, but the Special Committee considered this evidence useless and unreliable because former members of the Communist Party ‘could not be trusted.’ McGill’s six character witnesses, who had never had any involvement with the Communist Party, were simply dismissed as ‘incompetent,’ ‘except in one or two cases where it seemed possible to twist and distort [their testimony] into something disadvantageous.’ The court ignored McGill’s ‘quiet implication’ against Communism in the introduction to his book Emotion and Reason. It seemed no evidence would be considered valid, save a list of names of other former Communists.

McGill was aware that if he complied with the Committee’s request for names, he might be rewarded. He wrote to Dorothy Moore that he knew a university lecturer with a ‘similar’ background who provided a McCarthyist panel with names and subsequently ‘not only retained his position but was promoted.’ But McGill wasn’t about to give in. He had prior experience with bullies like the Special Committee. McGill wrote that, ‘in 1941, just before leaving the [Communist] party, I failed to reveal to the Rapp-Coudert Committee the fact of my membership. Had I admitted my membership I could have been forced to name others and thus to consign a number of families to suffering. My legal advice at the time was that I had but two alternatives: informing on others or misinforming the Committee. Even the Chairman of my [1954] Trial Panel insisted again and again that there is legally no “third alternative.” But of course there was … In 1941 I could have defied the Committee … It is the course I would have followed if I had envisaged it clearly.’

In the balmy early autumn of 1964, weeks before Hurricane Hazel swept through New York City, McGill was stripped at his professorship at Hunter College for ‘”neglect of duty” and conduct “unbecoming to a member of staff”.’ Despite six months of harassment, McGill had ‘refused as a matter of conscience’ to provide the Special Committee with names. McGill’s conscience was of no interest to the Special Committee, who told McGill ‘that employees of a public institution have no right to set their conscience or private judgment against that of their superiors.’

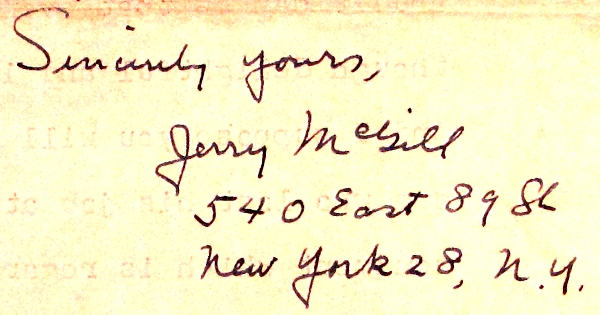

McGill was left jobless, a pariah to American universities. Yet he remained hopeful. He and his wife Helen had some savings with which they were able to support themselves and their 14-year-old daughter, and Helen continued to find work as children’s book illustrator after McGill’s dismissal. The couple was hopeful that McGill would find some position, if not in American universities (which feared the wrath of McCarthyist groups), then in universities abroad. ‘Eventually I know I will make a go of it,’ McGill wrote.

Indeed, he did. Dorothy and GE Moore were sympathetic to their friend’s plight, and he and Dorothy exchanged several subsequent letters in late 1954. Dorothy’s letters, which are not in the archive, must have contained a great deal of news about university positions outside of America, because McGill responded gratefully on several occasions, while updating her on his struggle to find employment. McGill found some work in 1955, and by 1956 was employed by Mortimer J Adler’s Institute for Philosophical Research in San Francisco. McGill’s career recovered, and he lived a long and seemingly happy life until his death in 1977 at the age of 79.

All quotes are from VJ McGill’s letters to GE and Dorothy Moore, which may be viewed in the Manuscripts Reading Room under class mark Add.8330 8M/14. Most of the information about the trial comes from letter Add.8330 8M/14/5. Records of McGill’s trial are held at the Elmer Holmes Bobst Library in New York City. A long biographical obituary of McGill can be found in the journal Philosophy and Phenomenological Research Vol. 38, No. 2 (Dec., 1977), pp. 283-286.