Of hammers, bouts and bets: a guest post by Jaap Harskamp

An intriguing catalogue concerning the London auction of the possessions of prizefighter Tom Sayers (1826–1865)

An intriguing catalogue concerning the London auction of the possessions of prizefighter Tom Sayers (1826–1865)

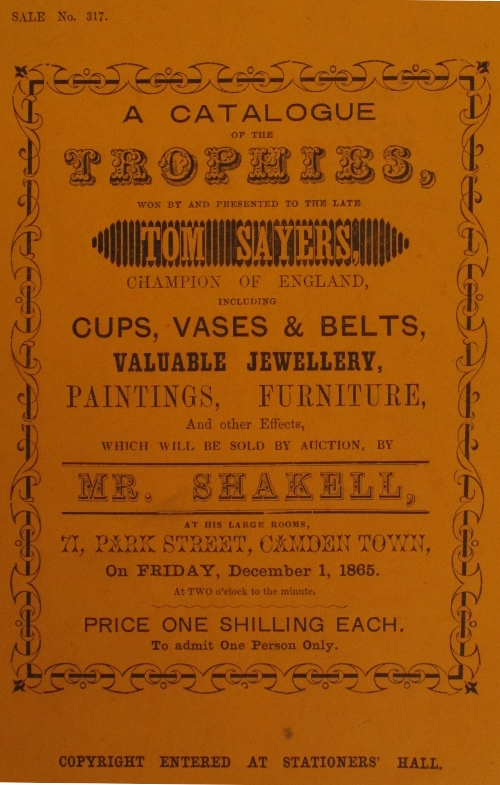

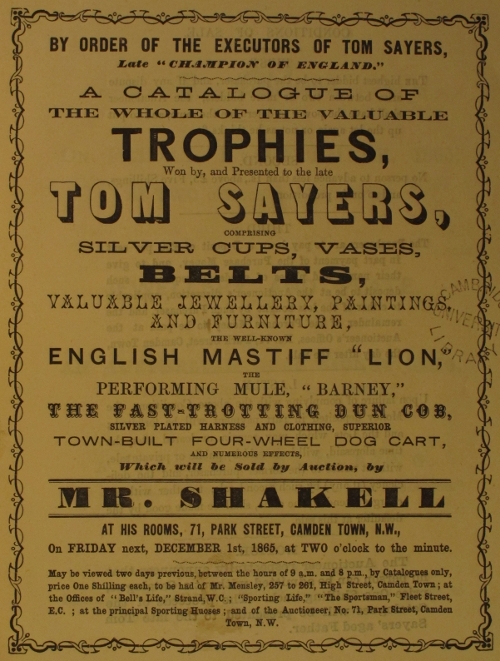

Being closely associated with the exploration and extension of the Lugt Online database, I have recently recorded the Library’s holdings of art sale catalogues up to 1901. Frits Lugt was both an art collector and an eminent scholar. He received his early training at the auction house of Frederik Muller in Amsterdam. It was there that he initiated a life time’s undertaking now known as the Répertoire des Catalogues de Ventes Publiques which, in four volumes covering the period 1600 to 1925, lists more than 100,000 art sale catalogues from various libraries in Europe and America. In this Répertoire, all catalogues are arranged in chronological order, giving date, place, order or provenance of each property, type of sale (whether pictures, prints, objets d’art or coins), number of pages and lots, auction house, library in which the catalogue may be consulted, and details of any annotations in the catalogue described (prices, names, additions, remarks). Brill/IDC has made the first three volumes (up till 1901) available online which allows for newly discovered material to be added on a continuous basis. The extent of the collection of catalogues at the Library may be limited, but Cambridge holds a significant number of unique items that are relevant to the database and have now been included in the online version of Lugt’s Répertoire. Those additions are largely catalogues of sales held in smaller towns and cities such as Cambridge, Norwich, Bristol, Taunton, Exeter, and elsewhere. One of those unique items is an intriguing catalogue concerning the London auction of the possessions of prizefighter Tom Sayers (UL classmark: 145.4.59(12)). The sale was held by order of the executors and took place at the rooms of Mr. Shakell, no. 71 Park Street, Camden Town on Friday 1 December 1865 at two o’clock to the minute (catalogue no. 317). 105 lots went under the hammer including twenty-seven sporting paintings, prints and photographs (with portraits of the prizefighter himself) and thirty-eight inscribed trophies, including his Champion Belt (lot 33).

The beginnings of boxing as a sport date back to 688 BC when the ancient Greeks included it as an Olympic game, being called ‘pygmachia’ (fist fighting). Fighters would wrap their hands and forearms with leather straps, sometimes studded with spikes (the cestus) as is shown by the bronze Boxer of Quirinal. This statue of Hellenistic athleticism dating from around 330 BC shows a powerful seated figure with a muscled torso and scarred face, cauliflower ears, broken nose, and a mouth suggesting broken teeth. In other words, everything we tend to associate with boxing. The sport was popular in Ancient Rome as part of gladiator contests. When the traditions of Ancient Greece and Rome fell into obscurity during the Middle Ages, boxing was eclipsed by pursuits like jousting, archery and hunting. European interest in recovering the traditions of Antiquity revived the passion for the sweet science of bruising, especially in England which is the true birthplace of prizefighting. At over 300 years, the Lamb and Flag tavern in Rose Street is the oldest (a rare survivor of the Great Fire) pub in the Covent Garden area. It was one of Charles Dickens’s favourite taverns. Its original reputation was a rather violent one. There have always been strong links between boxing and public houses. During the nineteenth century many publicans were ex-prizefighters and often had a boxing school and ring attached to their pub. The Lamb and Flag staged bare-knuckle fights in the seventeenth century. Matches took place on the cobbled front yard and more commonly in the back room which became known as the ‘Bucket of Blood’. The first recorded boxing match took place in Britain on 6 January 1681 when Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle, engineered a bout between his butler and his butcher. British aristocratic status and a passion for boxing went glove in glove. Boxing’s modern history started in the city environment of the early eighteenth century with the growth in popularity of bare-knuckle fighting. The spectacle of men beating, gouging and kicking each other senseless attracted an enthusiastic urban following. However, the world of prizefighting was populated with shady characters and dirty dealings. Early fighting had no written rules. There were no weight divisions or round limits, no rest periods, no points system, and no referee. A boxer was declared the winner when his opponent was no longer able to continue. An increasing number of aristocratic and wealthy patrons actively supported their chosen pugilists. As a consequence, betting on boxing rocketed. Huge wagers were put down on fights. With such large sums of money at stake, the need for rules in order to avoid foul play and settle disputes soon became clear.

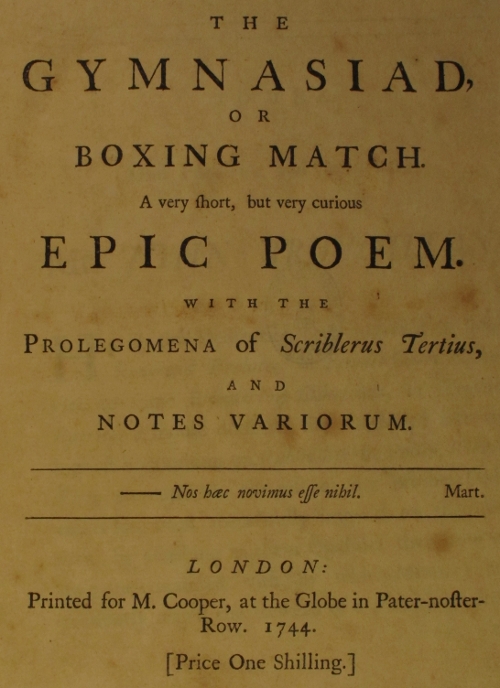

John ‘Jack’ Broughton (ca. 1703–1789), himself a former champion bare-knuckle fighter, was the first to codify a set of rules to be used in bouts of boxing. From 1743 onwards his seven conditions of fighting were imposed on those performing at his ‘Amphitheatre for Boxing’ (the largest and most influential venue of that kind at the time) in order to protect participants from serious injury or even death. Under these regulations, if a man went down and could not continue after a count of thirty seconds, the fight was over. Hitting a downed fighter and grasping below the waist were prohibited. These restrictions later evolved into the ‘London Prize Ring’ rules and formed the foundation of the sport that would become boxing, prior to the establishment of standards of conduct as we know those today. Broughton formulated his restrictions after George Stevenson, the so-called Coachman, died of injuries suffered in a fight with him. This fatal fight served as the inspiration for the mock-heroic poem ‘The Gymnasiad, or Boxing Match’ (1747) by Paul Whitehead containing the lines: ‘Down dropp’d the Hero, welt’ring in his Gore, / And his stretch’d Limbs lay quiv’ring on the Floor’ (UL classmark: S413.b.74.1(1)). Prizefighting was a rough game. To promote safety, Broughton also invented and encouraged the use of ‘mufflers’. These leather gloves padded with horsehair or lamb’s wool were used within his boxing academy during training sessions or exhibitions to secure his students ‘from the inconveniency of black eyes, broken jaws and bloody noses’(‘Daily Advertiser’ for 1 February 1747). Broughton himself came out of retirement and returned into the ring to settle a dispute with Jack Slack, a Norwich butcher who had allegedly insulted him. After fourteen minutes of exchanges Slack punched him right between the eyes, creating such a swelling that Broughton was forced to withdraw from the bout. The Duke of Cumberland, Broughton’s patron at the time, was said to have lost the huge sum of £10,000 on the match. He accused Broughton of throwing the fight. The aristocracy at the time was hooked on heavy gambling. Once again conceived as a problem in British society today, the habit has had a long and colourful history.

John ‘Jack’ Broughton (ca. 1703–1789), himself a former champion bare-knuckle fighter, was the first to codify a set of rules to be used in bouts of boxing. From 1743 onwards his seven conditions of fighting were imposed on those performing at his ‘Amphitheatre for Boxing’ (the largest and most influential venue of that kind at the time) in order to protect participants from serious injury or even death. Under these regulations, if a man went down and could not continue after a count of thirty seconds, the fight was over. Hitting a downed fighter and grasping below the waist were prohibited. These restrictions later evolved into the ‘London Prize Ring’ rules and formed the foundation of the sport that would become boxing, prior to the establishment of standards of conduct as we know those today. Broughton formulated his restrictions after George Stevenson, the so-called Coachman, died of injuries suffered in a fight with him. This fatal fight served as the inspiration for the mock-heroic poem ‘The Gymnasiad, or Boxing Match’ (1747) by Paul Whitehead containing the lines: ‘Down dropp’d the Hero, welt’ring in his Gore, / And his stretch’d Limbs lay quiv’ring on the Floor’ (UL classmark: S413.b.74.1(1)). Prizefighting was a rough game. To promote safety, Broughton also invented and encouraged the use of ‘mufflers’. These leather gloves padded with horsehair or lamb’s wool were used within his boxing academy during training sessions or exhibitions to secure his students ‘from the inconveniency of black eyes, broken jaws and bloody noses’(‘Daily Advertiser’ for 1 February 1747). Broughton himself came out of retirement and returned into the ring to settle a dispute with Jack Slack, a Norwich butcher who had allegedly insulted him. After fourteen minutes of exchanges Slack punched him right between the eyes, creating such a swelling that Broughton was forced to withdraw from the bout. The Duke of Cumberland, Broughton’s patron at the time, was said to have lost the huge sum of £10,000 on the match. He accused Broughton of throwing the fight. The aristocracy at the time was hooked on heavy gambling. Once again conceived as a problem in British society today, the habit has had a long and colourful history.

A main concern of sermons and pamphlets in the Elizabethan and early Stuart period was the playing of unlawful games in taverns and alehouses that involved gambling such as dice, backgammon and various card games (aided by the spread of cheap printed cards). In the plays of Ben Jonson and Thomas Dekker the alehouse appears as a meeting-place of vagabonds, robbers, whores and gamblers. Jonson’s gritty comedy The Alchemist for instance deals with such themes as greed, lust, prostitution and gambling. During the seventeenth century the number of fashionable gambling clubs gradually increased. Locket’s at Spring Gardens, Westminster, was the resort of the smart set. One of the regulars was dramatist George Etherege. In 1660, young George had composed his comedy The Comical Revenge or Love in a Tub which enjoyed enormous success. After a long silence, he wrote the 1676 play The Man of Mode or Sir Fopling Flutter, arguably the most sophisticated comedy of manners written in English. Etherege, at the same time, was a passionate gambler. In his ‘Song on Basset’ he celebrated a card game (bassetta) that had been introduced from the Continent to England during the later 1670s. Prohibited in France by Louis XIV in 1691, the game continued being played in England where it impoverished many noble families. Having learned basset at the London house of Hortense Mancini, Duchesse Mazarin, French mistress of Charles II, Etherege became one of its victims. The game deprived him of his fortune. He stopped writing and went in search of a rich widow instead. In London gambling gained wide popularity during the last two decades of the eighteenth century with the invasion of French émigrés fleeing the Revolution. During the Georgian, Regency and Victorian periods, gambling was endemic among the English upper classes. Beau Brummel and the Count d’Orsay had to flee to France when their gambling debts got too high. Young Charles James Fox, the future politician, would stay up for days gambling, drinking coffee to keep awake. At one point his father, Lord Holland, paid off almost £140,000 in gambling debts ran up by his son. Lord Byron’s daughter Ada, Countess of Lovelace, tried to use her mathematical talent to devise a system that would enable her to beat the odds at horseracing. She piled up large debts. By 1820 there were about fifty gambling dens in Central London. St James’s Street had become the site of a number of gentlemen’s clubs where betting was pursued in varying degrees. The undisputed king of London gambling from the late 1820s to the early 1840s was William Crockford (1775–1844), the founder and proprietor of the establishment bearing his name situated at no. 50 St James’s Street. The son of a fishmonger doing business at Temple Bar in the East End of London, he was an astute bookmaker originally connected to Newmarket racecourse. He saw an opportunity to reap rewards from the deep pockets of idle Regency dandies and aristocrats.

The puritanical forces of early nineteenth century ‘polite society’ rendered professional fisticuffs illegal. In a time marked by an ever increasing desire for all things moral and upright, boxing was deemed a low and demoralizing pursuit unfit for the education of a young gentleman. The rumours about excessive violence and thrown fights, its association with gambling and match fixing, gave pugilism a poor if not repugnant reputation. Prizefights were held at gambling venues and often broken up by police. Brawling and wrestling tactics in the ring continued. Riots at fights were common occurrences. The sport nevertheless flourished—and not necessarily underground. Boxing was wildly popular and some bouts attracted enormous crowds. Herefordshire-born Thomas Winter (1795–1851), son of a butcher, served an apprenticeship in his father’s trade. At the age of seventeen, he discovered his potential as a fighter. When he moved to London in early 1817 he had changed his name to Tom Spring. He soon established a solid reputation in the capital. After retirement of the legendary Tom Cribb, Spring claimed the championship of England and challenged all comers for three months on 25 March 1821. He retired for a time from the ring in order to keep the Weymouth Arms in Portman Square. On 20 May 1823, Tom Spring recommenced his career by fighting Bill Neat on Hinckley Down, near Andover, before a crowd estimated at 35,000. On 24 January he met Jack Langan, an Irishman, on the racecourse at Worcester, the stakes being £300 a side. Before the contest 1500 people (from a crowd estimated at 30,000) were thrown to the ground by the collapse of the grandstand, and twenty were seriously injured. A disorderly fight lasted two hours and twenty-nine minutes. At the 77th round Tom Spring had knocked Langan insensible. On 8 June, a second contest took place on a raised platform (to keep the crowds out, this time) at Birdham Bridge, near Chichester, the stakes being 500 guineas a side. Spring again showed his superiority. Some 20,000 people are said to have been present.

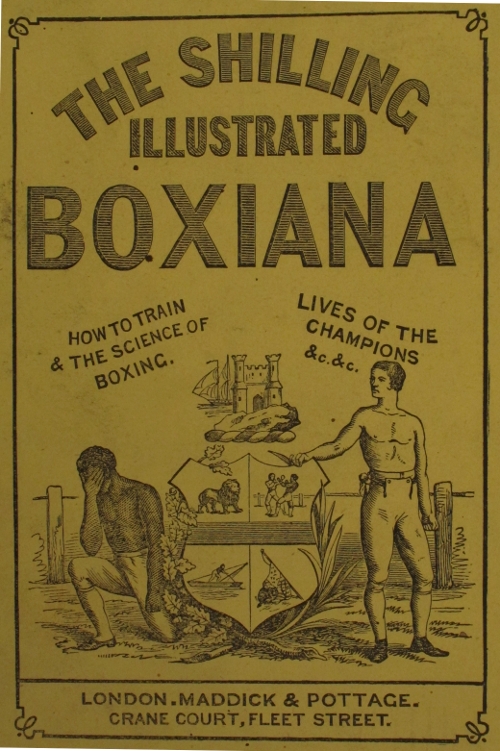

Boxing attracted aristocrats and artists alike. In 1819, caricaturist and illustrator Robert Cruikshank, the less well-known brother of George Cruikshank, designed a continuous strip-panorama which is over six metres long: ‘Going to a Fight’ (UL classmark: Harley-Mason.f.3) depicts a procession of carriages and carts and a medley of urban types, rich and poor, making their way from Hyde Park Corner, past a series of country taverns, to the ringside field at Moulsey Hurst in Surrey, on the south bank of the Thames, the venue of a number of notorious fights. This panorama is one of the most remarkable tributes ever made to the art of boxing. Between 1812 and 1828 Pierce Egan published his Boxiana; or, Sketches of Modern Pugilism which went through several editions in five expensive volumes. It was here that Egan started co-operating with the Cruikshank brothers, a working relationship that would later flower in his Life in London, the much plagiarized bestseller of the decade. The brothers contributed etchings to the early issues of the Boxiana. Egan charted the progress of bare-knuckle boxing from its emergence in the early eighteenth century to its decline in the 1830s. He included an anthology of pugilistic verse in the first volume of the series. The Irish poet Thomas Moore described him as ‘the Plutarch of the Ring’. Of Lord Byron it was said that on the day of his mother’s funeral, he occupied himself in sparring rather than escort the coffin into the family vault. Byron was in love with pugilism. He decorated his rooms in Cambridge with a screen illustrated with pictures of the most notable boxers and was a keen sparrer tutored in the rooms of former champion John ‘Gentleman’ Jackson, whom Byron referred to as my ‘corporeal pastor and master’. May poets of his day shared his passion. John Keats, John Clare, John Hamilton Reynolds and Thomas Moore all shared an enthusiasm for the sport. Essayist William Hazlitt left a series of celebrated written portraits of Bentham, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Poussin, and others. He leapt to fame in 1814 with his review of Edmund Kean’s performance of Shylock. Throughout his life he was fascinated by powerful performances, whether by boxers, rope-dancers or Shakespearean actors. In the February 1822 issue of New Monthly Magazine, he published an essay entitled ‘The Fight’ which is an account of the bout between Bill Neate, the Bristol Butcher, and Tom Hickman, the Gas Man (so called because his punches put the lights out), which had taken place on 11 December 1821. The contest lasted for eighteen bloody rounds before Neat reduced Hickman to senselessness and won the bout. Carrier pigeons were released to take the good news to Bill’s wife in Bristol and a medal was struck to commemorate the fight. The most telling indication of the status and wide popularity of boxing occurred at the coronation of George IV on 19 July 1821 where eighteen specially selected pugilists guarded the entrance to Westminster Abbey.

Boxing attracted aristocrats and artists alike. In 1819, caricaturist and illustrator Robert Cruikshank, the less well-known brother of George Cruikshank, designed a continuous strip-panorama which is over six metres long: ‘Going to a Fight’ (UL classmark: Harley-Mason.f.3) depicts a procession of carriages and carts and a medley of urban types, rich and poor, making their way from Hyde Park Corner, past a series of country taverns, to the ringside field at Moulsey Hurst in Surrey, on the south bank of the Thames, the venue of a number of notorious fights. This panorama is one of the most remarkable tributes ever made to the art of boxing. Between 1812 and 1828 Pierce Egan published his Boxiana; or, Sketches of Modern Pugilism which went through several editions in five expensive volumes. It was here that Egan started co-operating with the Cruikshank brothers, a working relationship that would later flower in his Life in London, the much plagiarized bestseller of the decade. The brothers contributed etchings to the early issues of the Boxiana. Egan charted the progress of bare-knuckle boxing from its emergence in the early eighteenth century to its decline in the 1830s. He included an anthology of pugilistic verse in the first volume of the series. The Irish poet Thomas Moore described him as ‘the Plutarch of the Ring’. Of Lord Byron it was said that on the day of his mother’s funeral, he occupied himself in sparring rather than escort the coffin into the family vault. Byron was in love with pugilism. He decorated his rooms in Cambridge with a screen illustrated with pictures of the most notable boxers and was a keen sparrer tutored in the rooms of former champion John ‘Gentleman’ Jackson, whom Byron referred to as my ‘corporeal pastor and master’. May poets of his day shared his passion. John Keats, John Clare, John Hamilton Reynolds and Thomas Moore all shared an enthusiasm for the sport. Essayist William Hazlitt left a series of celebrated written portraits of Bentham, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Poussin, and others. He leapt to fame in 1814 with his review of Edmund Kean’s performance of Shylock. Throughout his life he was fascinated by powerful performances, whether by boxers, rope-dancers or Shakespearean actors. In the February 1822 issue of New Monthly Magazine, he published an essay entitled ‘The Fight’ which is an account of the bout between Bill Neate, the Bristol Butcher, and Tom Hickman, the Gas Man (so called because his punches put the lights out), which had taken place on 11 December 1821. The contest lasted for eighteen bloody rounds before Neat reduced Hickman to senselessness and won the bout. Carrier pigeons were released to take the good news to Bill’s wife in Bristol and a medal was struck to commemorate the fight. The most telling indication of the status and wide popularity of boxing occurred at the coronation of George IV on 19 July 1821 where eighteen specially selected pugilists guarded the entrance to Westminster Abbey.

Tom Sayers (1826–1865) was an English boxer of Irish descent who during his career as a bare-knuckle fighter was defeated only once in sixteen bouts. His younger days were tough. He was born in a slum in Pimlico not far from Brighton’s Royal Pavilion, the son of a shoemaker. The inhabitants of the area were mostly fisherman and the gardens in front of the houses stank of the intestines of fish. Other inhabitants were former farm labourers who, unable to find work in the countryside, had brought their pigs and chickens to the inner city. The area was infested with rats and vermin. The miserable living conditions caused frequent epidemics of whooping cough, smallpox, or scarlet fever. Sayers was a bricklayer by trade and worked on the city’s London Road Viaduct which was completed in 1846. By this time Tom had already turned to prizefighting. Although ‘Brighton Titch’ Sayers was only a smallish man and never weighed much more than 150 pounds, he frequently fought much bigger opponents. In a fighting career that lasted until 1860, Sayers gained the heavyweight title of England in 1857, defeating William Perry, known as the ‘Tipton Slasher’. He became the last holder of the title before the introduction of the Queensberry rules in 1867. Sayers was also the first English boxer to fight an international championship match when he accepted a challenge from American Heavyweight Champion John Camel Heenan (1833–1873). Known as the ‘Benicia Boy’, the latter had made name for himself as an ‘enforcer’ in rigged elections in and around the sweatshops of the steamship dockyards at Benicia, San Francisco. Gambling backers had nominated him as the all American champion. Vocal efforts to halt the lawless proceedings were brushed aside and the prospect of the fight caught the public imagination on both sides of the Atlantic. In England, according to The Times, it ‘led to an amount of attention being bestowed on the prize ring which it has never received before’, while The New York Clipper observed that ‘fight, fight, fight is the topic that engrosses all attention’.

It must have been an extraordinary spectacle to those who, on the early morning of 17 April 1860, witnessed the massive crowds making their way to Waterloo Station. Everybody seemed to be leaving the capital. They swamped the London platforms for the fleet of south-bound ‘specials’. Three-guinea tickets were stamped ‘To Nowhere’. What was the destination of those who rushed towards the trains? They all hurried to a small village in rural Hampshire. The fields near the tiny village of Farnborough soon spilled over and were black with people. Twenty-five year old Heenan, who was also of Irish descent, was both taller and three stone heavier that Sayers. Despite injuring his right arm early in the bout, Sayers seemed to dominate the fight with blood pouring from Heenan’s face and his right eye bruised and closed. But after more than forty rounds, Heenan appeared to gain the upper hand as he choked Sayers against the top rope, causing the crowd (populated by the likes of the young Prince of Wales, Charles Dickens, William Thackeray, Thomas Nast and various aristocrats and Members of Parliament) to cut the ropes and spill into the ring. After two hours twenty-seven minutes and forty-two rounds the Aldershot police, brandishing a magistrate’s warrant, stormed the scene and brought proceedings to a halt.The referee declared a draw. The two men shared the purse of £400. The fight between Sayer and Heenan is remembered in one of the street ballads collected by John Ashton in 1888 which is entitled ‘The Bold Irish Yankey Benicia Boy’. The ballad’s final verse reads as follows:

When Heenan came to England, far from a distant land,

They said he was a fool to come, to face an Englishman,

But they were all mistaken when they saw the glorious battle,

Heenan cooked the champion’s bacon, and made his daylights rattle.

A painting commemorating the fight between Sayers and Heenan was produced by Jem Ward, himself a former prizefighter and English Champion from 1825 until 1831. He was also the first boxer to be disciplined for deliberately losing a fight. In retirement he kept the York Hotel in Liverpool, where he was taught to paint by William Daniels. He became a proficient artist exhibiting his work in London and Liverpool.

Sayers and Heenan became close friends after the fight, touring the country together and staging theatrical re-enactments of their famed fight, but Sayers’s boxing days were over. A public subscription was made for his benefit which raised £3,000. This—by the standards of the day—vast sum of money was collected in such places as the House of Commons and the Stock Exchange. The collection was tangible evidence of the large number of aristocratic patrons of an illegal sport. Such leading establishment figures as the Earl of Derby were among Sayers’s patrons who gambled heavily on the outcome of his fights. All his contests had taken place following ‘underground’ advertising away from the gaze of the authorities. One who had beat a hasty retreat when the Hampshire police moved in towards the ring was the Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston. Within days he had to reply to sharp questions in the House of Commons. The immediate outcome was a call for new codes of conduct and stricter regulations. By 1865 the set of ‘Dozen Rules’, drawn up by the London Amateur Athletic Club, was accepted by Parliament. That document laid down the sporting rules as we know today, three-minute rounds with a minute’s interval, gloves worn, ringside stanchions padded, ten second counts at any knockdown, and ‘no cross-buttock throwing whatever’. John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry, sponsored the new disciplines that bear his name. After retiring from the ring, Sayers found a new and suitable career. Having purchased Howes and Cushing’s circus which included two well trained performing mules named Pete and Barney, he set up and managed his own show—and not without initial success. Opened in 1862, Wolferton was a railway station on the King’s Lynn to Hunstanton line. It was the nearest station to Sandringham House and stop for the royal trains until its closure in 1969. The twenty-first birthday of Prince Albert on 3 June 1886 saw a special royal train bring the Sayers’s Circus to Wolferton for a performance at the palace. After the event, one of the elephants refused to climb back on to the train, and was tied to a lamppost which it promptly uprooted, before demolishing the station gates and then calmly boarding its truck.

Unable to make the circus pay, Sayers called it a day, bought a house in Camden Town, and settled down. He became a familiar figure driving his carriage through the local streets accompanied by his dog, a mastiff called Lion. Barney remained a member of the household (the mule was one of the last lots at the sale of the fighter’s possessions). Sayers succumbed to the idle temptations that money provide and fell into a dissipated lifestyle that wrecked his health. Five years after retirement he died of diabetes and tuberculosis at the age of thirty-nine. Such was his fame that his burial at Highgate Cemetery was attended by 10,000 people. The funeral took place on 15 November and was by all accounts a riot. The Daily News described the scenes as disgraceful. Soon after midday a vast and rowdy crowd had assembled around the Mother Red Cap public house in Camden High Street. At the cemetery itself the gates were guarded by policemen who with the use of force tried to limit the number of people entering the cemetery. The tombs and crypts nevertheless were crowded with persons who jostled and laughed, trampled on the grass, and defiled the graves. They were pushing and fighting in order to secure vantage ground from which to see the procession. By four o’clock a brass band playing the ‘Dead March’ approached. Hearse and mourning coaches slowly made their way through the surging mob. Sayers’s pony and dog-cart with his magnificent mastiff as the sole occupant followed immediately after the hearse. As the coffin was taken into the chapel, the crowd forced their way into the graveyard, the police temporarily unable to stop them. They subsequently rallied, and once more succeeded in closing the cemetery gates. The scenes were unparalleled in the dignified history of Highgate. Tom’s burial was turned into a battlefield.

His supporters and friends subscribed for the erection of a large tomb, bearing a statue of his beloved guard dog. Sayers was elected to the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1954 and since 2002 Sayers’s former home at no. 257 Camden High Street carries the English Heritage blue plaque. But that was not the end of the story. In November 2011 a handwritten signed letter from Tom Sayers addressed to John Camel Heenan in which the former accepts the conditions and stakes for a fight for the championship of England and America to be staged in Britain was brought under the hammer by Heritage Auctions in Dallas. The page may be heavily creased and scattered with stains and chipping, but the writing has survived with remarkable boldness. The literal transcription of the letter reflects the level of education Sayers had received during his younger years in Brighton’s Pimlico:

Dear Sir, I aksep yor Chalang tue fite without gloves oktuber 24. Yrs. truly Thomas Sayers. staiks £500 a side, J.C. Heenan Esq.

What had happened to Lion, Sayer’s faithful mastiff? The dog was one of the last lots to be auctioned at the Camden Town sale. Unfortunately, the catalogue does not contain any annotation, prices or names, but it seems safe to assume that Lion found another loving home with one of Tom’s many admirers. If every picture tells a story, then many a sale catalogue contains the potential for a novel.

References

John Ashton, Modern Street Ballads (London: Chatto & Windus, 1888). Classmark: Ver.7.88.4

Robert Cruikshank, Going to a Fight: being the sporting world in all its variety of style and costume along the road from Hyde Park Corner to Moulsey Hurst (London: Sherwood, Neely & Jones, 1819) [a continuous strip view in a boxwood drum]. Classmark: Harley-Mason.f.3

Pierce Egan, Boxiana, or, Sketches of ancient and modern pugilism from the days of the renowned James Figg ad Jack Broughton to the heroes of the later Milling Era Jack Scroggins and Tom Hickman: a selection / edited and introduced by John Ford (London: Folio Society, 1976). Classmark: Waddleton.b.9.404 & 9415.b.525

Nat Fleischer and Sam Andre, A pictorial history of boxing / revised and brought up to date by Sam Andre and Nat Loubet (London: Hamlyn, 1998). Classmark: 2000.11.1520

Tom Sayers, A catalogue of the whole of the valuable trophies: won by, and presented to the late Tom Sayers, comprising silver cups, vases, belts, valuable jewellery, paintings, and furniture, the well-known English mastiff ‘Lion’, the performing mule ‘Barney’, the fast-trotting dun cob, silver plated harness and clothing, superior town-built four-wheel dog cart, and numerous effects, which will be sold by auction (London: R. E. Taylor steam printer, 1865). Classmark: 145.4.59(12)

Paul Whitehead, The gymnasiad, or Boxing match. A very short, but very curious epic poem, with the prolegomena of Scriblerus Tertius, and notes variorum (London: M. Cooper, 1744). Classmark: S413.b.74.1(1)

Alan Wright, Tom Sayers: the last great bare-knuckle champion (Lewes: Book Guild, 1994). Classmark: 9004.c.4306

Pimlico is / was surely not near/in Brighton ???

Many thanks for your query. Apparently there was an area of Brighton called Pimlico: see, for example, http://www.nlcaonline.org.uk/page_id__26_path__0p18p110p.aspx.

It’s intriguing to learn about the early days of boxing, with no formal rules and the emergence of regulations by figures like Jack Broughton to ensure the safety of participants and fairness in the sport.