Laurence Sterne’s tercentenary: a guest post by Mary Newbould

Laurence Sterne (1713-1768), one of the most celebrated comic writers of his and perhaps of all time, celebrates his tercentenary this year. Sterne’s special relationship with Cambridge has continued from the eighteenth century to the present day: he was an undergraduate at Jesus College, which had strong family associations, whilst Cambridge University Library now houses one of the most significant collections of work by and about Sterne. We are marking this tercentenary with a virtual exhibition of a selection of just a few items from this wonderful collection.

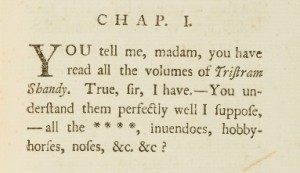

Sterne fully launched his career as a fiction-writer with The life and opinions of Tristram Shandy, gentleman. Hailed as one of the great comic novels, it was published in five instalments over a period of seven years between 1759 and 1767. Sterne’s contemporaries found Tristram Shandy to be quaint, eccentric, infuriating, baffling, amusing, entertaining, prurient – but above all it attracted the public’s attention, especially at first. Its games with typography provided one source of comment: Sterne is inordinately fond of the dash and the asterisk, uses diagrams and pictures in the text, and even includes black, marbled, and blank pages to confound and amuse his readers.

Yet Tristram Shandy is much more than just an entertaining distraction from the ‘typical’ types of fiction with which his early readers would have been familiar – Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novel Pamela, for instance, or Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones. Sterne’s work offers an incisively comic take on a range of weighty philosophical concepts, from John Locke’s theory of association to recent ideas about conception and childbirth. Furthermore, the dominant voice of the outré, inimitable Tristram signally changed how the introspective first-person narrator would be treated in subsequent prose fiction.

As the 1760s wore on and new volumes appeared, however, Tristram Shandy seemed to lose its novelty appeal. As Horace Walpole, never one to mince his words, observed: ‘the dregs of nonsense, have universally met the contempt they deserved. Genius may be exhausted – I see that Folly’s invention may be so too’. A new kind of fiction increasingly seemed to attract readers that was now stamped by sensibility – a highly refined state of emotional and intellectual being, characteristically manifested in body language such as sighing, weeping, and fainting. The later volumes of Tristram Shandy, in fact, show a greater awareness of sentimentalism, with key passages such as ‘The Death of Le Fever’ quickly gaining public approbation.

Sterne further developed his approach to sensibility in his subsequent work, A sentimental journey through France and Italy, published just shortly before his death in 1768. Sterne’s ‘sensibility’, however, is never straightforward: his fictionalised account of continental travel undertaken by the self-styled ‘Sentimental Traveller’, Yorick – a character who first appeared in Tristram Shandy and under whose name this Anglican clergyman had even printed his own sermons – is riddled with the ironic treatment to which sensibility, in its worst excesses, could be exposed.

Sterne made a lasting impression on his contemporary and subsequent readers, both those for whom the satirical humour and wit of Tristram Shandy holds considerable appeal, and for those seeking the emotional thrills (or the piquant irony) found in the novel’s sentimentalised passages and more fully in A sentimental journey. Sterne’s readers consistently left a trail of commentary and criticism found in such typical outlets as newspaper and magazine reviews that testifies to this enduring interest. His works have continued to be reprinted ever since their first appearance, alongside new editions of his Sermons, of his correspondence, and of the anthologies of favourite extracts which increasingly became popular among late eighteenth-century readers: The beauties of Sterne (1782) is the most famous example from a highly successful series giving a range of authors similar treatment.

An even more diverse and surprisingly expansive picture of Sterne’s reception is discernible in the enormous array of imitative works his fiction has inspired. ‘Sterneana’ encompasses not only prose parodies of Tristram Shandy and A sentimental journey, but poems, songs, dramatic pieces, and texts which imitate Sterne’s distinctive typography. The visual appeal of his work, in fact, also generated a vast number of illustrations based on and relating to both novels, and to Sterne himself, in an age during which the cult of the celebrity author was gradually gaining sway. Images inspired by Sterne and his fiction have appeared in book illustrations, prints, paintings, graphic satire, and objects ranging from Wedgwood ceramics to decorative fans, from the eighteenth century to the present day. Martin Rowson’s graphic novel version of Tristram Shandy and Michael Winterbottom’s film based on the novel, A cock and bull story, offer just two examples of the unprecedented ways in which contemporary readers continue to express the excitement and enjoyment they find in Sterne by producing new adaptations of his fiction.

Guest author: Dr Mary Newbould, Wolfson College, Cambridge.

Adaptations of Laurence Sterne’s Fiction: Sterneana, 1760-1840, published in August 2013 by Ashgate, is an engaging study of these imaginative responses to Sterne’s fiction in the early period of his reception by Cambridge-based scholar M.-C. Newbould. Its chapters cover material ranging from imitative, satirical prose pamphlets from the early 1760s, to travel writing – sentimental journeys and eccentric travel narratives alike – to dramatic adaptations, to visual Sterneana. Much of the material used in this book belongs in the invaluable Oates collection held at Cambridge University Library, which complements the Sterne archive assembled by Kenneth Monkman, former curator of Shandy Hall, Coxwold – the author’s former home, and now the visitable property of The Laurence Sterne Trust. Adaptations of Laurence Sterne’s fiction joins a host of events based at Shandy Hall and elsewhere celebrating the birth of an author whom one contemporary reviewer described as ‘the inimitable LAURENCE STERNE’.

Dr Newbould talks about Sterne in this video presentation.