Charles I and the Eikon Basilike

The heavily symbolic frontispiece to Eikon Basilike. The crown in the upper right corner is ‘beatam & aeternam’ (blessed & eternal), which is to be contrasted with the temporal crown at the King’s foot, ‘splendidam & gravem’ (splendid & heavy). He holds the martyr’s crown of thorns, ‘asperam & levem’ (bitter & light). London: 1649 – CCD.8.9

At about 2pm on this day in 1649, King Charles I was beheaded outside the Banqueting House of Whitehall Palace. The story of his downfall is soon told; his belief in the Divine Right of Kings and apparent Catholic sympathies led to unpopularity with the people and Parliament, the ultimate result of which was Civil War from 1642. In 1645 he was imprisoned and refused to give in to the demands of his captors for a constitutional monarchy, and when Oliver Cromwell took control of the country in 1648, his fate was sealed. The scene on that bitterly cold morning was set in the introduction to printed editions of the King’s speech:

“About ten in the morning the King was brought from St. James’s, walking on foot through the park, with a regiment of foot, part before and part behinde him, with colours flying, drums beating…some of his gentlemen before, and some behinde bareheaded, Dr Juxon next behind him…”

When the moment came, the King made a short speech and prayed with Dr Juxon, Bishop of London. The King said:

“I go from a corruptible, to an incorruptible Crown; where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the World.” [Dr Juxon replied] “You are exchanged from a Temporal to an eternal Crown; a good exchange.”

Dr Juxon’s comment echoes the sense of martyrdom felt by the King’s supporters; people who had witnessed his unpleasant end were said to have dipped their clothes in his blood, locks of his hair circulated, and items which had belonged to him took on the status of relics. In 2010 a small exhibition of such relics was mounted, in the London jewellers Wartski (see their ‘Exhibitions & Events’ page), including the silver chalice from which the King took communion on the morning of his execution, the pearl earring he wore that day and locks of his hair. The King’s words continued to be heard after his demise through a work purporting to be his spiritual autobiography, which may have been penned by John Gauden, Restoration Bishop of Exeter. Whoever the author, Eikon Basilike (The Royal Portrait) was immensely popular, and appeared in many editions by the end of the year. The Library holds over fifty copies of the text, in various languages, most of which are gathered together at the classmark CCA-E.8. A description of the collection, on which this post is based, has recently been added to the Library’s webpages.

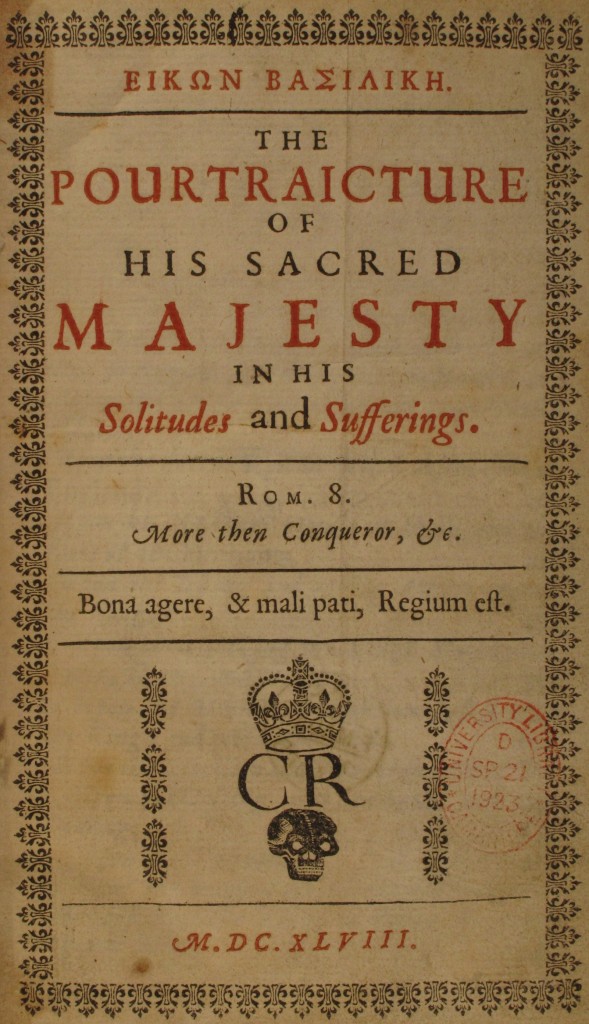

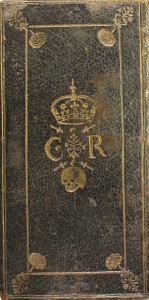

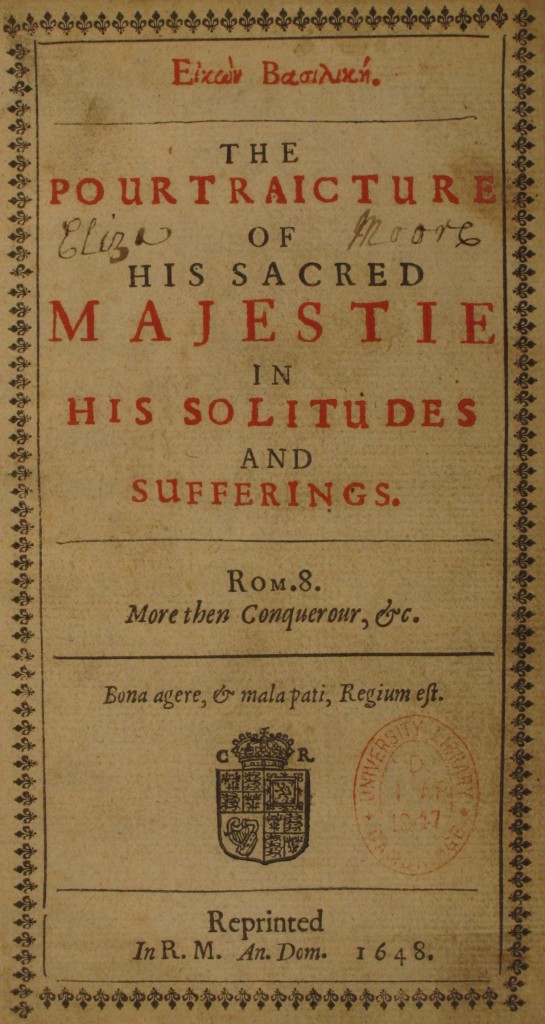

Title page to Eikon Basilike (London: 1649), CCD.8.2. Notice the ‘CR’ with the crown and skull; a similar device appears on the binding of CCE.8.20

The sixty-five volumes shelved at CCA-E.8 form a significant collection of works by and about King Charles I. The majority of the collection consists of copies of the Eikon Basilike (hereafter, Eikon), which claimed to be the King’s spiritual autobiography. Purported to have been written by the King shortly before his execution on 30th January 1649, printed copies may have been available on (or slightly before) [1] the day of the King’s execution and by the end of the year about thirty five editions had appeared. Controversy over the King’s authorship raged for some time before the connection with John Gauden, Restoration Bishop of Exeter (and alumnus of St John’s College), was made at the end of the seventeenth century. It is now generally agreed that Gauden is likely to have compiled the text using some authentic writings of the King as a foundation. The majority of the collection (fifty nine volumes) was given to the Library by Francis Falconer Madan (1886-1961) over a period of more than three decades, between 1923 and 1956. A civil servant, Madan was the son of Falconer Madan (1851-1935), Bodley’s Librarian from 1912 to 1919. The younger Madan was the author of what remains the most extensive study of the Eikon, based on his own collection (begun by his father) and published by the Oxford Bibliographical Society in 1950. His work built upon that of Edward Almack (1852-1917), whose Bibliography of the King’s Book (1896) pioneered the study of the Eikon.

At the core of the collection is around fifty copies of the Eikon printed in England or on the continent in 1649 or 1650, of which thirty seven edition are in English. The text was suppressed by Parliament, so it was illegal for printers to print it and for booksellers to sell it. Most editions therefore give very little information about their production on the title page, where one would usually expect to see the place of printing, the printer’s (and occasionally publisher’s) name and address. Given the secrecy with which copies of the text had to be produced, establishing the order in which the various editions appeared and by whom they were printed is not an easy task. Consequently the identification of printers with particular anonymous editions has often been achieved by comparing their decorative initials and type with those of known printers of the day. Many copies are pocket-sized, which allowed them to be easily concealed by their owners. Regarded by many of the original owners as a poignant memento of the King, the book has long been attractive to collectors, and some of our copies were previously part of large private libraries. Editions also appeared in Latin, French, German and Dutch. There are further copies of the text scattered throughout the library in other distinct collections, including the Royal Library (the collection of Bishop John Moore, presented by King George I in 1715), the library of Sir Geoffrey Keynes (acquired in 1982) and that of the Rousseau scholar R. A. Leigh (acquired between 1982 and 1985). At least two copies, in the collection known as the Stars, have been in the library since the seventeenth century; one belonged to John Hacket (it is inscribed ‘J. H.’), chaplain to Charles I and Charles II who was appointed Bishop of Lichfield at the Restoration.

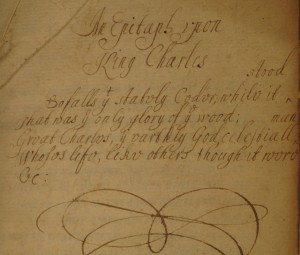

Transcribed into the back of this copy (CCD.8.18) by a seventeenth-century owner is the beginning of ‘An epitaph upon King Charles’, which appears (signed ‘J. H.’) at the end of some editions of the Eikon

A copy of the 1687 folio edition of the ‘Works of King Charles the Martyr’ was previously owned by Professor Edward Solly (1819-1886), whose library was sold at Sotheby’s over six days in November 1886. It contained around sixty-five copies of the Eikon, in addition to multiple copies of other seventeenth-century works by or about the King, but the 1687 edition of the ‘Works’ is not listed in the sale catalogue. Solly wrote a short article on the Eikon, published in the Bibliographer in 1883, but his hopes of compiling a more detailed study were cut short by his death three years later. A copy of the Eikon itself (with the imprint ‘Reprinted in R.M. for James Young, 1648’) was owned by the wonderfully named Frederick Adolphus Philbrick (1835-1910), a philatelist and judge. His library – which included incunabula and fine bindings – was sold by Sotheby’s on 29-31 May 1905 and contained more than eighty copies of the Eikon. Several volumes in our collection once belonged to Charles Edward Doble (1847-1914), Assistant Secretary to the Oxford University Press, and two contain the bookplate of Edward Almack himself. Another was given to the Library by Sir Henry Francis Herbert Thompson (1859-1944) of Trinity College. After training to be a barrister, then turning to medicine, he became an Egyptologist and left some of his rare books to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. His papers are in the University Library.

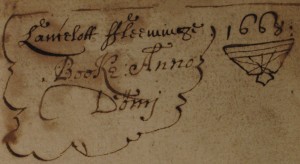

The earliest dated inscription in the collection – “Launcelott Fleeminge[‘s] Booke Anno Dom[in]i 1668” – at the rear of the copy at CCE.8.23.

Several volumes in the collection contain dated inscriptions of the seventeenth century: ‘Liber Jacobi Maddocke…1692’, ‘Anthony Lechmere 1690’ (possibly of the Lechmeres of Hanley Castle, Worcestershire), ‘Tho[mas] Edgar 1669’ and ‘Launcelott Fleeminge 1668’ (possibly the Lancelot Fleming born c.1634 in Kippax, Yorkshire, who died in 1717). A number of the volumes were owned by women. One copy contains the inscriptions ‘Sarah Needham 1712’ and ‘Eliza Fay’ (of the late-seventeenth or early-eighteenth century) and another is inscribed ‘Eliza Moore’ (of a similar date).

The sombre binding (rear board) of CCE.8.20, with the ‘CR’ monogram, crown and skull. This binding is a mere 114mm tall.

A large proportion of the collection survives in contemporary bindings, the sombre style of which echo the emotion of the time; Almack spoke in 1896 of the books as ‘to this moment wearing mourning for Charles the First’. Several bear the gilt monogram ‘CR’ (for Carolus Rex), which is often accompanied by a crown and skull. One copy (the third issue of the first edition) has inside each cover two black and white silk bands, which a note inside the front cover calls ‘mourning bands’. Interestingly, two copies of the same edition (CCC.8.1 and CCC.8.2) are in identical polished calf bindings of the seventeenth century, the pastedowns of which are from the same early sixteenth-century edition of Ludolphus de Saxonia’s Vita Christi, as yet unidentified [2]. This may indicate that both copies (and probably many more of the same edition) were properly bound by the publisher or printer before sale, rather than being sold in temporary (cheap) bindings or in sheets for the purchaser to have bound themselves.

This collection, largely the gift of F. F. Madan, is a resource of immeasurable wealth for those interested in the Eikon. The large number of different editions in one library allows one to study and understand the way in which the various editions were produced, and copy-specific features including bindings, bookplates and annotations allow one to find out how the books were used, received and thought of by readers from the seventeenth century through to the twentieth.

Footnotes

[1] See pp. 164-165 in Madan, A new bibliography of the Eikon Basilike of King Charles the First (Oxford Bibliographical Society, New Series, Vol. III, 1949). The publisher Richard Royston recalled later that early in October 1648 he received an order from Charles I to prepare his press, and that he received the manuscript, via Edward Simmons (the King’s chaplain) on 23rd December. The printing was entrusted to John Grismond and proof sheets are known to have been at Simmons’ house by 7th or 14th January 1649. Grismond’s printing house was raided and the edition (apparently completely) destroyed, so Royston moved a press outside the city where the work was completed, selling 2000 copies through street hawkers at fifteen shillings each. John Gauden’s wife recalled that her husband ‘could by no means get the book finished till some few days after his Majesty was destroyed’, but a letter to Dr Sheldon suggests that copies were available on the day of the King’s death. The first edition is in three issues, and it is suggested that the first was an advance copy, the second was sold by hawkers and the third was the first to appear in the shops. Madan records that George Thomason inscribed his copy (the third issue) with the date ‘Feb. 9’ and Almack, noted that a copy of the second issue of the first edition was inscribed ‘February 13’ (see Madan, 1949, p. 11).

[2] The front pastedown (there is no rear pastedown) in CCC.8.1 contains part 2, chapter 72, and the rear pastedown in CCC.8.2 contains part 1, chapter 68. The edition has not been ascertained, but it is clearly early sixteenth century, and from a relatively large volume (there are two columns to a page, each being 89mm wide, not including printed marginalia). It is none of the following, which have been ruled out either by the type, the arrangement of text or the page size: Paris 1502 (Ulrich Gering & Berthold Rembolt), Paris 1509 (Berthold Rembolt), Lyon 1510 (Stephan Gueynard), Paris 1517 (Berthold Rembolt), 1519 Lyon (Martin Boullion), Lyon 1522 (Giunta), Paris 1529 (Christian Wechel), Lyon 1530 (Antoine Blanchard), Paris 1534 (Chevallonium), Paris 1539 (Thielmann Kerver).

Dear Liam,

I was wondering if there was any notes/additions/marginalia on the editions that you have in your collection, except the ones you have discussed in this article. I am currently making a PhD on Eikon Basilike and its reception. Did readers leave any marks?

Best regards,

V. CHAISE

Vanessa,

Thank you for your comment. Some do have annotations, but I’ll drop you an email with some further information.

Best wishes,

Liam.

Hi Liam

I have recently bought an oil painting from a car boot sale that is the exact same as the Eikon Basilike picture that is in this article.

The canvas I have seems to be very very old,i have had someone look at the wood that is in the canvas and have been told that it is over 300 years old

Your picture is the only I can find on the internet and I would love more information on my oil painting

Great article. I was wondering if the style of printing is known? The development of mezzotint in 1642 was distinctive because it introduced a way to produce tones or varying shades of black. From what I have read though, it seems that the frontispiece was woodblock; but would that technique apply to the rest of the book? Probably not. Most likely only for illustrations. The main body of the work was probably metal movable type since it was introduced in 1450. Any information would be wonderful.

Thanks Bill. As far as I know the frontispiece is engraved (i.e. onto a sheet of metal) by William Marshall, and yes, the text is with moveable metal type. There aren’t usually any other illustrations within the book, though some have portraits of Charles II and other related individuals.

I am looking for some critical material on the text. Can you help me with that.

Hi there, we think we might have a first edition of this book and would love to send pictures of it incase you can confirm!

Dear Liam,

Thank you for this article – it is incredibly interesting. I’m currently preparing to begin my undergraduate thesis on annotations to the Eikon Basilike and readers’ approach to the text and am wondering if you knew how many annotated editions there are in the collection?

Thank you, and all the best,

Eva

Hi Eva. I’ll email you directly. Thanks! Liam Sims, Rare Books Specialist