Thomas Erpenius: an Arabist of many talents

Thomas van Erpe, or Erpenius, as he is usually known, is best remembered for his collection of Arabic manuscripts which came to the University Library following his death from the plague in 1624. These were acquired after complex and protracted negotiations involving the University Librarian, Abraham Whelock, and George Villiers the 1st Duke of Buckingham, and arrived in 1632. They formed the basis to which were added all the later Arabic manuscript collections which came to the Library in later centuries.

Erpenius was born in 1584 at Gorchum in Holland and entered the University of Leiden where he studied oriental languages. Early in his career he travelled in Europe, including a visit to Cambridge, adding to his language skills and contacting like-minded scholars including the English Arabist William Bedwell, who also became his teacher. During this time he also collected manuscripts and books relating to his studies wherever he could and which eventually grew into a notable library. On his return to Leiden he became the Professor of Arabic and spent the rest of his life in academic pursuits. But apart from his talents as a collector, what is less well-known, is that Erpenius was also a significant author in his own right and the owner of his own printing house for the production of books using Arabic script.

The early part of the seventeenth century was a time of important developments in Arabic studies in the Universities in England and in Europe; the Chair of Arabic at Cambridge was founded in 1632 and the Oxford Chair in 1636. There was also a flourishing group of Arabic scholars in Leiden of whom Erpenius was only one. Notable figures included Joseph Scaliger (1540-1609), a widely travelled scholar of the Classics and Arabic and Professor at Leiden, Franciscus Raphelengius (1539-1597), a scholar, printer and Professor of Hebrew in Leiden and Jacob Golius (1596-1667) an Arabist who was Erpenius’ most distinguished pupil.

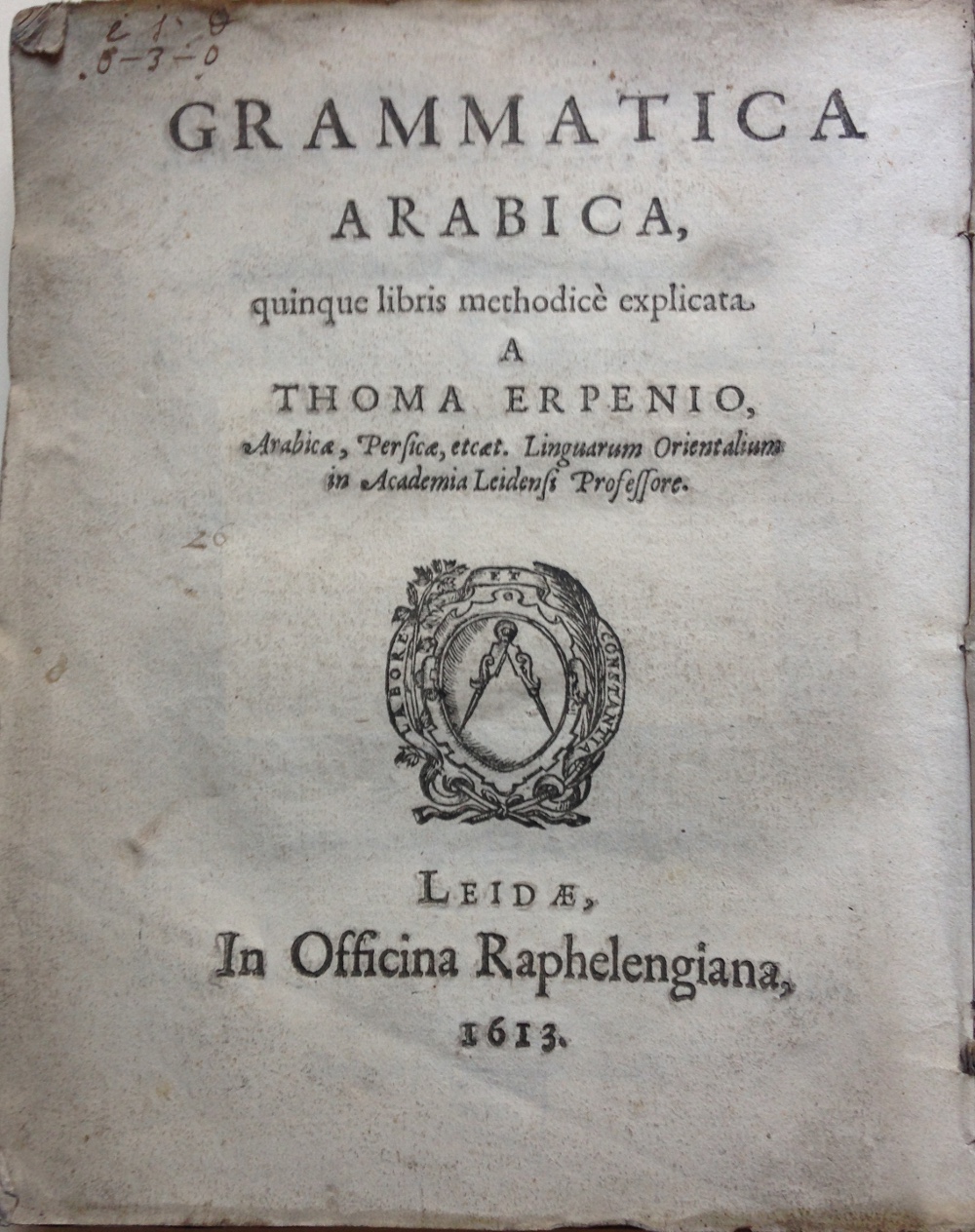

This group of scholars were enthusiastic about the development of Arabic studies and were keenly aware of the lack of good reference sources and texts for language teaching which were only partly provided for from their own collections of manuscripts and printed books. Erpenius especially was aware of this lack and his answer was to write his own grammar book which became a standard work and which was reprinted many times. The first edition of his Grammatica Arabica was published in 1613. It was the first scientific Arabic grammar to be written in Europe, written somewhat in the style of a Latin grammar, and it was reprinted many times and used as an Arabic language textbook until the 19th century in European universities.

Among Arabic scholars of earlier centuries there were, of course, also many distinguished grammarians. Notable among them are Ibn Malik (1204-1274), the Arab grammarian born in Spain and later a teacher of grammar in Aleppo and Damascus, and al- Makkūdī (d.1405) the grammarian from Morocco. Al- Makkūdī was the author of one of the most popular Arabic grammatical works, the Sharḥ Alfīyah and Erpenius had in his own manuscript collection a copy of al-Makkūdī’s commentary on the Sharḥ Alfīyah (Ms. Mm.6.23). Here, his copy shows pages covered in examples of marginalia and commentaries written by Erpenius on the original Arabic work, perhaps preparatory work for his own printed grammar.

Also, the early 17th century saw the development for the first time of printing in Arabic script in moveable type in Europe, and Leiden was also in the forefront here. The development of printing in Arabic was complicated because of the cursive nature of the script and the large number of characters which were needed for a complete font. However, Franciscus Raphelengius, the colleague of Erpenius, was also the son-in-law of Christopher Plantin the Antwerp printer and the manager of the Plantin office in Leiden. It was Raphelengius who was responsible for the production of the first Arabic typeface used in Leiden and who printed the first edition of the Erpenius Grammatica Arabica in 1613 (Huntingdon.55.12).

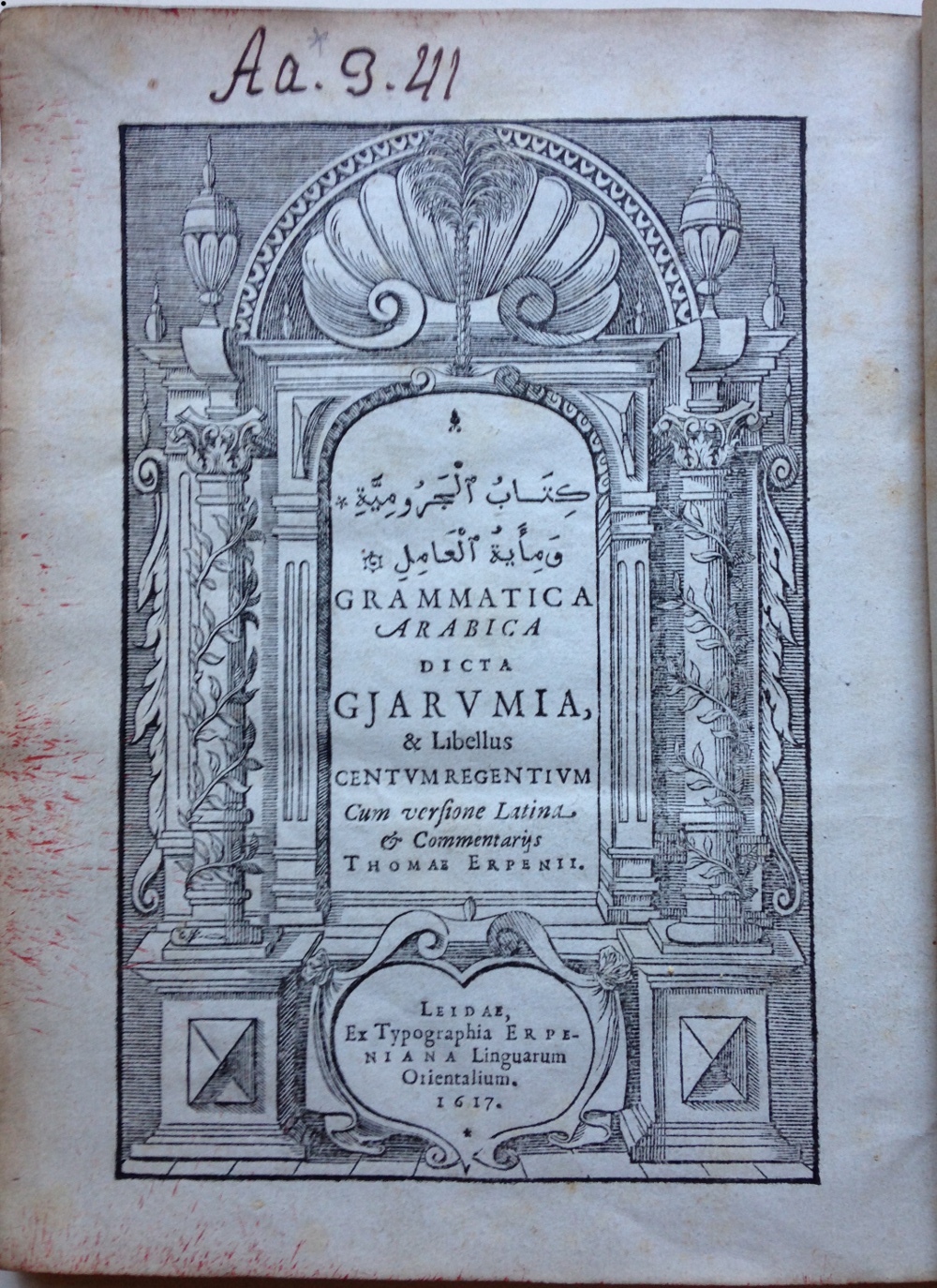

In 1614 disaster struck for Erpenius with the sudden death of the Arabic typesetter left him with books to publish but no means of carrying this out. As a result of this, Erpenius made the decision to set up his own printing workshop which he established in his own home. His first publication came out in 1615 and he continued to use this method of producing his own books until his death in 1624. The typeface he developed was in a different style to that of Rephelengius; a smaller more elegant type with smaller characters based on those of the Medici Press in Rome. From the printing press of Erpenius himself there are five items in the Library’s collection; these include the 1617 edition of his Grammatica Arabica (Aa*.3.41) on the title page of which Erpenius appears as both author and printer.

Although the Erpenius manuscript collection came to Cambridge, the later whereabouts of the type font is unknown. It was at one time thought that this also came to Cambridge with the Erpenius manuscripts where William Bedwell was keen to obtain an Arabic font to print his Arabic dictionary over which he slaved for so long. But there is no evidence to support this idea and it is most likely that the typeface came into the possession of the Elzevir family of printers and was used in their Arabic publications.

I read this piece with great interest. I have two comments, though.

My first point concerns the printing history of Erpenius’ grammar. The author first refers to Erpenius’ Arabic grammar (1613), and then she writes ‘the 1617 edition of his Grammatica Arabica (Aa*.3.41)’. She includes an image caption, which also suggests that the latter is the second edition of the former. This is not quite as the author present it. In fact, the volume edited, translated and printed by Erpenius in 1617, transmits an entirely different text: the Ajrummiyah, a popular Arabic textbook written by the Moroccan scholar Ibn Ajurrum, and not the grammar composed by Erpenius. [Ajrummiyah had been printed previously by the Typographia Medicea in Rome, in 1592, under the editorship of a certain Davidus Alsanhagius.]

The title-page provided above also makes this distinction. The full-title of the 1617 edition reads Grammatica Arabica dicta Gjarumiya … cum versione Latina & Commentariis Thomas Erpenii , as opposed to Grammatica Arabica … a Thoma Erpenio (1613). Erpenius’ own Arabic grammar is divided into five chapters following Latin grammatical concepts. In his rendering of the Ajrummiyah, on the other hand, Erpenius quotes manageably short pieces of text from the Arabic original, gives a literal Latin translation, which is then followed by his commentary explaining difficult terms and points.

My other comment is with regards to the transfer of Erpenius’ books to Cambridge and the fate of his fonts. Upon the death of Erpenius in 1624, his oriental book collection became available for sale. His manuscripts were acquired by George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, in 1625, and subsequently bequeathed to Cambridge University by his widow. His press, however, was bought by Isaac Elzevier and the typefaces continued to be employed for printing in Leiden. The punches and matrices of this font have survived and are now kept in the offices of Joh. Enschedé printing company in Haarlem.

The excellent new book by Arnoud Vrolijk and Richard van Leeuwen, Arabic Studies in the Netherlands: A Short History in Portraits, 1580–1950 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2014) has an image of the punches and the matrices from the Erpenius press (p. 36), among other interesting oriental printing paraphernalia.

Dear Nil – Thanks for your very helpful comments. After a closer look at the two publications on grammar by Erpenius which I mention in the blog, I realise that they are not two editions of the same work but do vary in their content as you describe. We also have four later editions of works on grammar by him which appear to be closer in content to the 1613 edition rather than the 1617 publication. In relation to the typefaces it has always been thought a possibility that they came to Cambridge with the manuscripts where they were intended to be used to print William Bedwell’s dictionary which still remains here in manuscript form. I read the Vrolijk and van Leeuwen book with great interest, after the blog had been written, and it is great they were able to throw light on the fate of the punches so that it is no longer a mystery.

according to several bibliographies-

there exists a targoom (targum) manuscipt to the ketuvim = prophetic writings. dated as 1347

is there a way someone can digitize it- and if not professionally- ill pay someone with a smart phone to take pictures of it and send it to me so i may study it from the oldest source available

If you think this manuscript is in our collection, could you email mss@lib.cam.ac.uk directly to enquire about imaging? Thanks.