Beasts in the University Library

Guest post by Harriet Hale, Graduate Library Trainee at Trinity College. Cambridge.

One of the great things about a traineeship in Cambridge is that, with the central cluster of departmental and college libraries as well as the public Central Library and main University Library, there always seems to be something book-related going on. For the Science Festival, 10-23rd March 2014, the University Library welcomed festivalgoers for a number of talks examining the more technical side of books, including ‘Beasts in the University Library,’ examining the creation and conservation of parchment.

Our first speaker, Shaun Thompson, took us through preparation techniques involved in making skin into parchment. The animal skin (usually sheep, cow, pig or goat,) is first washed to rinse away preservation salt, blood and organic matter and to prepare it for the slaked lime (an alkaline mix of limestone and water that can break down proteins and fat, well-known in its ability from as early as the 3rd century.) Workers would use wooden poles to move the skins around as the mixture would otherwise have a similar effect on their own skin! Then the skin is de-haired by scraping, removing sweat glands, pores and surface imperfections and rinsed again until the water runs clear, returned to a second lime bath and again scraped clean.

What makes the material unique is the stretching process – tied onto ‘pippins’ (small knots or pebbles) and then attached to a wooden frame, the skin is tensioned to thin it evenly and stop it from becoming inflexible and transparent. The skin fibres also realign on the frame to become horizontal rather than vertical. A lunellum (semi-circular or moon-shaped (lunar) knife,) is used to scrape the skin when stretched on the frame, and pumice or chalk is rubbed on the surface them removed. This treatment removes both the epidermis and hypodermis to leave only the dermis as the layer that makes up parchment.

What makes the material unique is the stretching process – tied onto ‘pippins’ (small knots or pebbles) and then attached to a wooden frame, the skin is tensioned to thin it evenly and stop it from becoming inflexible and transparent. The skin fibres also realign on the frame to become horizontal rather than vertical. A lunellum (semi-circular or moon-shaped (lunar) knife,) is used to scrape the skin when stretched on the frame, and pumice or chalk is rubbed on the surface them removed. This treatment removes both the epidermis and hypodermis to leave only the dermis as the layer that makes up parchment.

As a bit of an etymology enthusiast, I was interested to learn the connection between the word parchment (in Latin ‘pergamentum’) and Pergamon credited as its birthplace, and that vellum is from the same root as veal (‘vélin’) so refers specifically to calf/cowskin.

The second talk, given by conservator Anna Johnson, focused on parchment damage and conservation. The majority of materials the department deals with on a daily basis are organic – made from plants (paper) or animals (leather, parchment,) and as such are damaged by similar factors – light, UV radiation, water and fluctuations in the moisture content of the air and environment. Parchment specifically can sustain damage such as warping and distorting from heat changes, becoming brittle or breaking down into gelatine.

Although water is sometimes used in conservation – when distorted or stiff, parchment can be relaxed with water vapour – this requires a very carefully controlled application of moisture over a long period of months or even years. For the most part only necessary changes are made, e.g. relaxing creases just enough that they do not obscure text. Too much water can cause a great deal of damage, particularly when twinned with heat. The London Metropolitan Archives’ ‘Great Parchment Book’ was partially relaxed manually and then fully flattened digitally – a technique that is likely to gain support in an increasingly technological age, improving accessibility of the text as well as conservation.

In order to accurately gauge damage caused to parchment, extracted fibres can be looked at under a microscope. Parchment is made up primarily of collagen – a protein built in a triple helix of polypeptide chains (these protein chains occur in different formations for silk, keratin and collagen, but contain the same elements.) The molecular composition of the collagen includes carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen in groups of two hydrogens and one nitrogen (amine group) and two oxygens, hydrogen and carbon (acid group.)

Like rope, collagen is made up of layered fibres. The largest is the elementary fibre, which is made up of fibrils, themselves made up of microfibrils. The strength and durability of parchment crucially depends on collagen fibres holding together, yet over time the fibres can fragment and unravel. Once damaged, the collagen risks turning to gelatine, which has the same chemical makeup as collagen but a different (unsuitable!) structure. There is usually a layer of gelatine on the top of healthy parchment, but in order for the parchment to remain in good condition, it is important that much of the collagen stays intact. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that once collagen turns to gelatine it can never be turned back.

The IDAP method (Improved Damage Assessment of Parchment), developed by a team at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, uses 100x magnification to examine tiny extracts of parchment and identify damage. The damage types we were shown included frayed, split, flat, cracked, shrunken, bundles, gel-like and gelatine.

After the talk, we got a demonstration of the effects of water and heat on parchment where we were able to personalise our own bits of parchment, immerse them in water and then observe the effects of ironing the wet parchment. The parchment shrunk significantly, and became brittle and translucent.

Our final talk was on determining the species type of parchment. Emma Nichols explained that the first go-to indicator of species is the size of the writing area – whilst you may be able to get a whole large map out of a 100x150cm bullskin, you would not get more than a couple of leaves out of a sheepskin (which conventionally/usually only stretches to around 48x66cm.) Different animals also have distinctive hair follicle patterns, although these are difficult enough to see in leather and almost impossible in fine parchment.

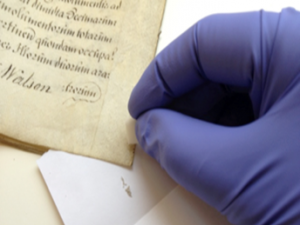

One non-destructive method of species identification is parchment sampling, as practised by the BioArCh (Biology, Archaeology and Chemistry) team at the University of York. Their method involves collagen analysis through mass spectrometry, where “erdu” (leftover particles from using an eraser on the parchment) are tested and both the species of animal and the condition of the manuscript can be ascertained. The eraser is rubbed 30-40 times on the manuscript, always in the margin where no damage can be done to the text, then the erdu is transferred to a vial to be tested. Gloves and erasers are changed between manuscripts to avoid cross-contamination.

One non-destructive method of species identification is parchment sampling, as practised by the BioArCh (Biology, Archaeology and Chemistry) team at the University of York. Their method involves collagen analysis through mass spectrometry, where “erdu” (leftover particles from using an eraser on the parchment) are tested and both the species of animal and the condition of the manuscript can be ascertained. The eraser is rubbed 30-40 times on the manuscript, always in the margin where no damage can be done to the text, then the erdu is transferred to a vial to be tested. Gloves and erasers are changed between manuscripts to avoid cross-contamination.

At the lab, collagen is then removed from the erdu, treated with trypsin, and put through a mass spectrometer. Different animals have a different mass of peptide chains, so the particles move at a different rate. Discovering the species of a leaf of parchment is not only interesting as a novelty, it can assist in interventive conservation. For example, if the parchment comes from a calf, the conservators can use beef gelatine for repairs instead of that made from sheep. Identifying the species of lots of manuscripts whose provenance is known has also revealed that sheep were most frequently used for parchment in England, cows in France and goats in Italy. This information can help in localising other manuscripts, for example, a ‘Paris Bible’ written on goatskin may, in fact, be Italian.

Mass spectrometry also gives feedback on the level of damage to the collagen that cannot be seen with the naked eye through a ‘quality index.’ Treatment can then be tailored for specific type of parchment and level of damage. (The reading of erdu will, however, only be from the top layer of the manuscript, and only from the area the rubbings are taken, so cannot provide a reliable quality reading for the entire manuscript.) Finally, we got to sew together a small booklet to take home, giving us an idea of how parchment would have been bound.

The sheer breadth of knowledge made it a fascinating set of talks. The most refreshing and rewarding aspect of the experience was hearing about the day to day work of the conservators – there was a welcome lack of dumbing down, and enough information to really pique my interest.

Reposted with permission from CaTaLOG, the Cambridge Trainee Librarians Online Group blog.