William Bedwell: the tribulations of an Arabist

William Bedwell was an Arabic scholar and mathematician born in Great Hallingbury, Essex, in 1563. He is sometimes known as the father of Arabic studies in England, but he encountered many trials and setbacks during his career, so that the full extent of his achievements can be underestimated. It was as a student at Cambridge that he first encountered a circle of scholars with interests in Biblical studies and Semitic languages and encouraged by this stimulus, he progressed rapidly with his studies in Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, and later, in Arabic. In 1595, he began an ambitious project to write an Arabic–Latin dictionary, which became a lifetime’s work, and which he had hopes would be the first of its kind to be published in Europe.

He made contacts with other important scholars of the time such as Lancelot Andrewes (Master of Pembroke College and Bishop of Ely), and he developed a close friendship with the noted Huguenot language scholar, Isaac Casaubon. Through him he also met the Dutch scholar Thomas Van Erpe, to whom he also gave some tuition in Arabic; another famous pupil was Edward Pococke, the future Professor of Arabic in Oxford.

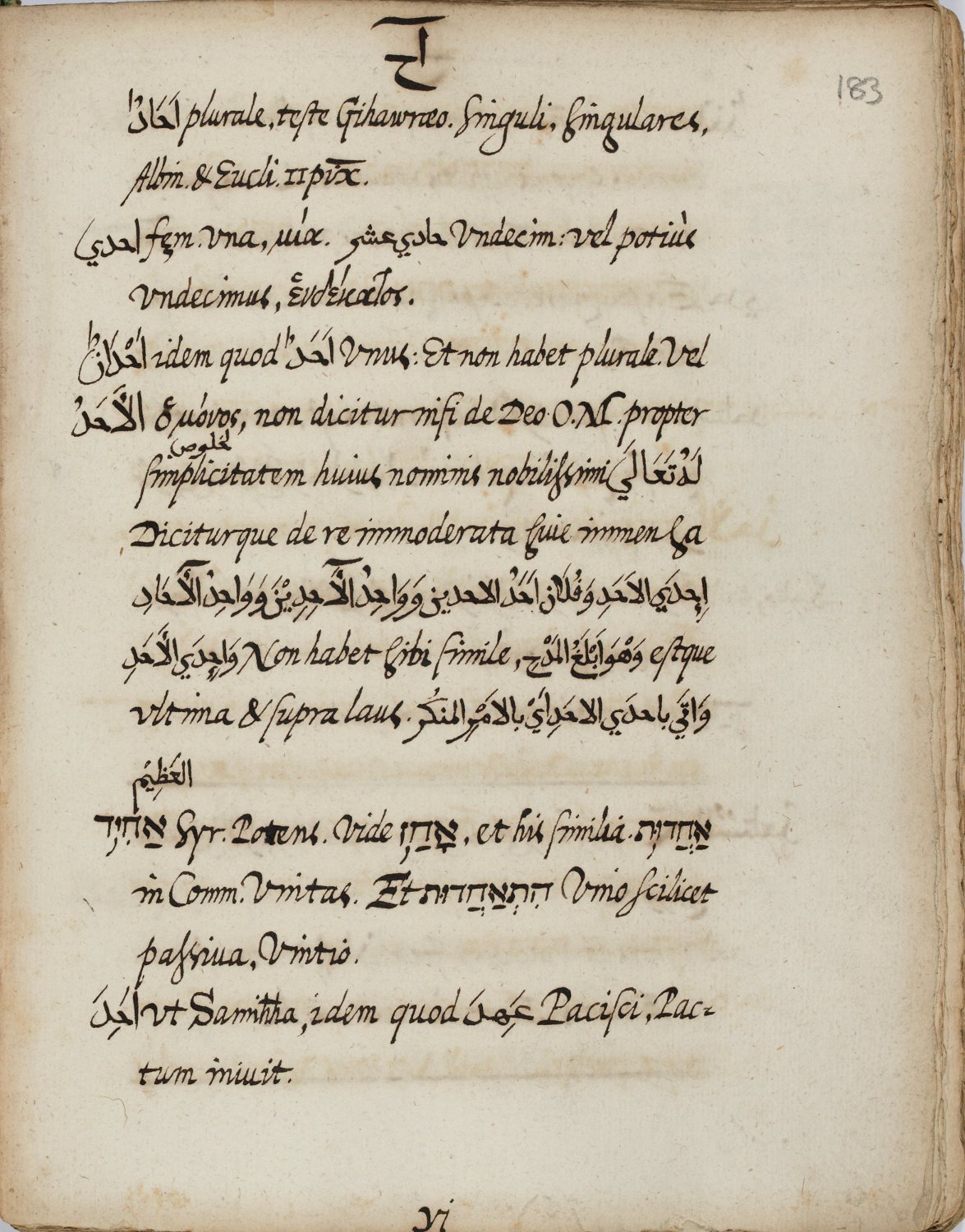

Leaf of the first volume of Bedwell’s lexicon in Arabic and Latin, also showing his use of Hebrew roots. Ms Hh.6.1 l.183

Bedwell’s progress with learning Arabic was, all along, hampered by the lack of relevant texts and reference sources available in England at the time. So, in 1612, he travelled to Holland to consult Arabic manuscript collections there. Leiden had become a famous centre for Arabic studies and important figures there included Joseph Scaliger, Conrad Vorstius and Thomas van Erpe. The Dutch also possessed the finest printing presses for Arabic script in northern Europe at that time. The Dutch scholars Frans Raphelengius and his sons were also printers of Arabic texts for Plantin in Antwerp, and Bedwell intended to investigate the possibility of printing his works there, or even to purchase an Arabic type font to publish his dictionary back in England.

Bedwell’s knowledge of Arabic was also based on his own readings of texts and eventually his dictionary reached a total of nine volumes, with additional paper slips inserted between the pages. After completing seven volumes of this work, he came across a copy of the Qamus of Firuzabadi, the famous Persian grammarian, and in the light of this extra knowledge, added yet more definitions. The manuscript of the dictionary was seen by many of the Arabic scholars of the age, and was much admired, but it was doomed to remain unpublished as the Arabic type punches and matrices he had succeeded in purchasing in Leiden proved unequal to the task of printing it. Following his death, Bedwell’s dictionary came to the Library in Cambridge, where it was consulted by, among others, Edmund Castell during the creation of his monumental Lexicon Heptaglotton printed in 1669.

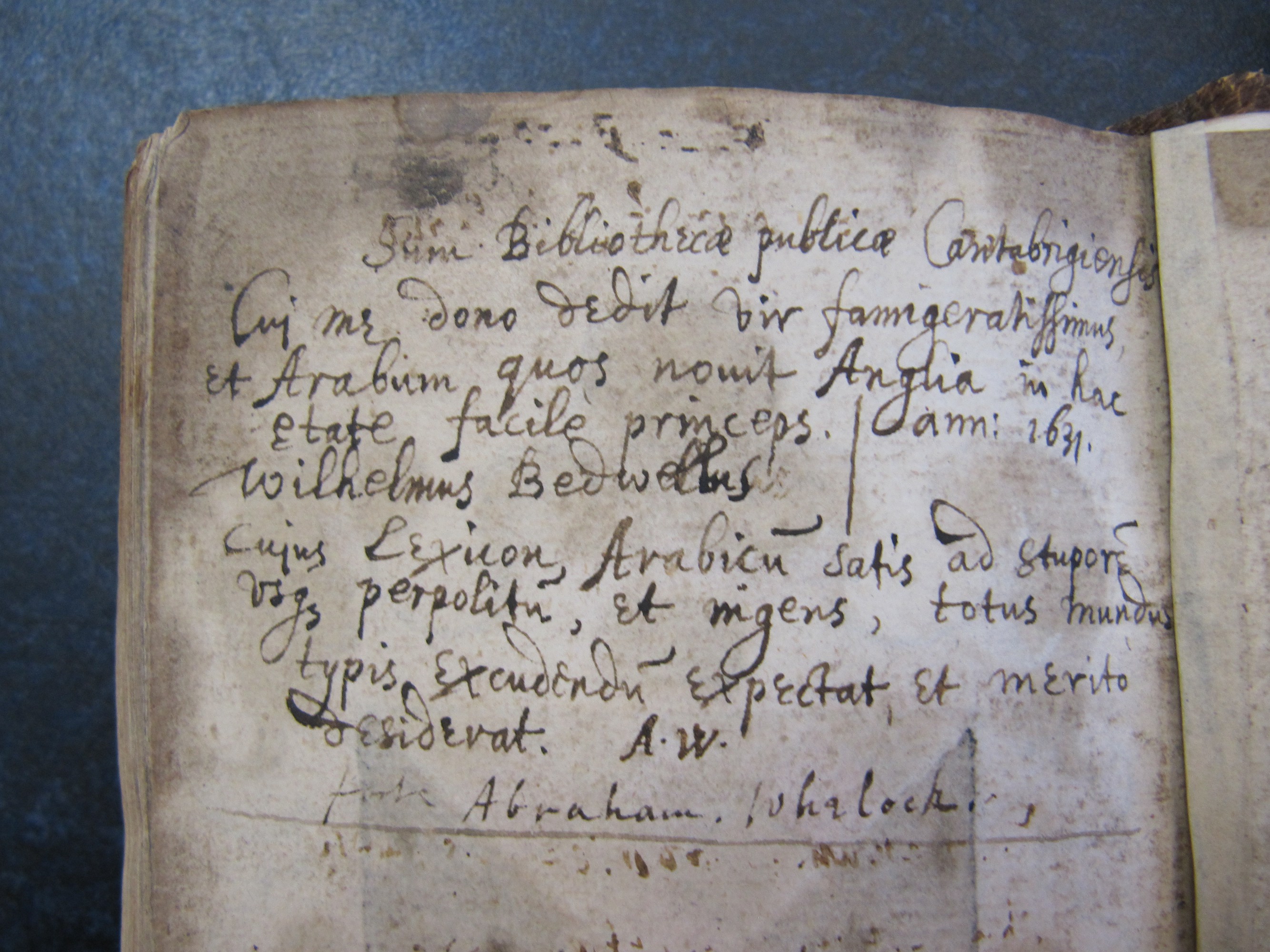

Dedication on the first leaf of Bedwell’s Qur’an; the first Arabic work to enter the Library’s collections. Ms Ii.6.48 l.1

In the early years of the seventeenth century the University Library did not have a single Arabic work in its collections. Bedwell changed this by donating his own copy of the Qur’an which came to the Library after his death in 1631. On the first leaf of the manuscript can be seen the dedication by Abraham Whelocke (1593–1653), the first Professor of Arabic in Cambridge and also the University Librarian. He was keen to develop Arabic collections here and was later to be instrumental in acquiring the manuscripts of Thomas Van Erpe.

Arabic was a neglected subject in Europe in the sixteenth century and students were hampered in many ways in their endeavors. There was a lack of original texts and reference sources, travel to the Middle East was fraught with dangers and they also faced a real prejudice against the study of Islamic subjects. Bedwell struggled on in the face of all these difficulties; he was noted for his friendships and the encouragement of others and for his teaching and sharing his expertise. However, success with his own publications met with problems throughout his career. His dedication to the study of Arabic was notable and tenacious and yet he often referred to himself as الفقر (al-faqīr), the humble one. According to some sources, it was Bedwell, and not Thomas Van Erpe, who was thought to be the first to revive the study of Arabic in Europe.