The death of Captain Cook

A guest post by Julien Domercq, winner of the inaugural Cambridge University Library/History of Art Student Curatorial Competition and curator of the exhibition ‘The death of Captain Cook: mythmaking in print’

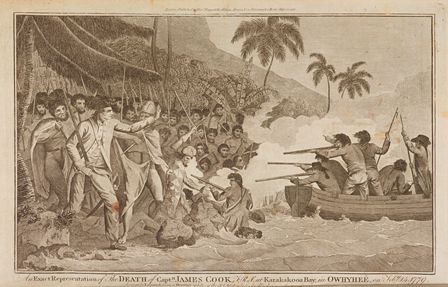

‘An exact representation of the death of Captn. James Cook, F.R.S. at Karakakooa Bay, in Owhyhee, on Feby. 14. 1779’. 1784. Lib.1.80.3.

Between 1768 and 1779, Captain James Cook (1728–79) undertook three voyages to the South Seas, resulting in the publication of three official accounts, as well as the first images of the Pacific to be disseminated in Europe. These journeys of discovery culminated in Cook’s death on 14 February 1779 in Hawaii. After the news had reached Europe, the event gripped the imagination of writers, poets and artists, who recognised in the account of the voyage – and in Cook’s tremendous achievements – the values of the Enlightenment.

‘The death of Captain Cook: mythmaking in print’, a new exhibition in the University Library’s Entrance Hall, traces the development of the print iconography of the death of Captain Cook. Whilst playing a central role in the mythologizing of Cook’s death, these prints, of varying quality and target audiences, also bear witness to the extent to which his discoveries of distant lands and cultures became appropriated into the visual language of European popular culture at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Michelangiolo Gianetti, whose elegy to Cook was published in 1785 by the Royal Academy of Florence, captured the widespread fervour following Cook’s death when he stated that the explorer’s virtues were ‘more worthy to be celebrated than the victorious prowess of military Chiefs, for he was “A Hero”, at once sailor, warrior and philosopher, who displayed the qualities of magnanimity, enterprise and tranquillity.’ The visual records of Cook’s first voyages had been dominated by Rousseauian ‘noble savages’, who lived in what was believed to be the new Arcadia and were perceived as intrinsically good, unencumbered by either civilisation or divine revelation. But representing Cook’s death posed a problem: how could the ‘noble savages’ have killed the greatest hero of the Enlightenment? There were no eyewitness accounts of Cook’s death, meaning that his heroic reputation developed and came to be interpreted in the light of artists’ pre-existing aesthetic loyalties. The resulting works sought not only to document but also to write history.

On 17 January 1779, the Resolution and Discovery, the two ships of Cook’s third and fatal voyage, anchored at Kealakekua Bay on the west shores of the island of Owyhee, now the island of Hawaii. The Englishmen received a warm reception; the bay was filled with more canoes than even the most experienced sailors had ever seen, packed with thousands of men, women and chiefs bearing presents. The ships left at the end of two bountiful weeks, but returned to the bay for repairs within days after the foremast of the Resolution was damaged in a storm. The explorers were surprised not to receive the same overwhelming reception as they had on their first anchoring, and the growing number of thefts and incidents on shore increasingly irritated and angered Cook. A long-standing anthropological debate continues to rage about how to explain this change of attitude: had Cook been perceived as the god Lono, and did his return fall within the season of a new god, prompting the Hawaiians’ wrath? On the morning of 14 February, Cook and his men woke to find that the Discovery’s cutter had been stolen during the night. The loss of the ship’s largest boat was a great blow to the expedition and Cook immediately went ashore to take hostage Terreeoboo, king of Owyhee, until the restitution of the boat. A skirmish broke out between Cook’s party and the Hawaiians: blows were exchanged and Cook killed a man, before the Hawaiians overwhelmed Cook and his nine marines, throwing stones and attacking them with spears, clubs and daggers. Having retreated to the shore, some of the marines were able to swim back to the boats, but Cook – who could not swim – was attacked and fell face down into the water, where he was stabbed, clubbed and drowned. As Cook fell, the marines aboard the boats discharged their muskets at the mob, while further out in the bay the Resolution and Discovery opened fire with their cannons. Cook’s body, which was only partially recovered in the days that followed, was committed to the deep on 22 February.

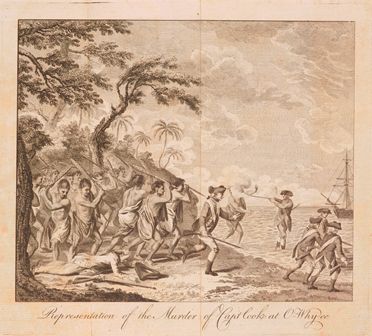

The news took nearly a year to reach London. A brief account of the navigator’s death, known as the Kamchatka dispatches, was sent by land via Russia and reached the Admiralty in London on 10 January 1780. The newspapers relayed the information the next day and the news spread across Europe. The return of the ships nearly a year later brought more details about the circumstances of Cook’s death. The details of the event captured the public imagination to such an extent that a vast number of unofficial accounts appeared before the publication of the official account in 1784. The only illustrated unofficial account published in 1781, a somewhat careless and sensationalist text based on the records kept by John Rickman, second lieutenant of the Discovery, opens the exhibition with its frontispiece depicting Cook dragged onto the shore after having fallen into the sea and been clubbed to death. Despite its generic depiction of Hawaiian landscape, costumes and weapons, this rather unheroic portrayal is probably, and paradoxically, the closest image we have of Cook’s demise. Another print on show, illustrating the popular smaller format edition of the voyage’s official account, depicts Hawaiians struggling for the weapon that killed, or is about to kill, Cook, some of them visibly trying to pacify the figure holding the dagger, therefore making the important distinction between the actions of one wicked individual and that of the group, seeking to preserve the myth of the ‘noble savage.’

Subsequent images attempt to elevate Cook to the status of hero and glorify his death. In that respect, the exhibition aims to show that the ‘Death of Cook’ by John Webber, official artist of Cook’s last voyage, was extremely influential as can be seen through a popular print on show illustrating Hogg’s 1784 popular opus on exploration voyages, A New, Authentic, and Complete Collection of Voyages Round the World, copied directly in reverse from Webber’s original. Cook is depicted about to be stabbed as he raises his arm to gesture to his marines in the boats to stop firing at the crowd. This image was not intended as an accurate representation of Cook’s death but rather served to depict Cook as a hero sacrificing his own life to prevent further bloodshed.

‘Neptune raising Captn. Cook up to immortality, a genius crowning him with a wreath of oak, and Fame introducing him to History’. 1790. RCS.Case.a.107.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, tributes to Cook moved from depictions of his death to more allegorical subjects. The exhibition includes Johann Heinrich Ramberg’s frontispiece for Thomas Bankes’s 1790 A Modern, Authentic and Complete System of Universal Geography, representing Cook being received into glory. This frontispiece, while celebrating Cook as a patron of geographical discoveries, also prefigures the submission of the world to the nascent British Empire, depicting the four corners of the world presenting Britannia with offerings in gratitude for bringing the benefits of civilization to the world.

The nineteenth century and its advances in commerce and technology made the ‘noble savage’s’ way of life seem inferior and doomed to extinction. The peoples of the Pacific, regarded as exotic and captivating in the eighteenth century, were increasingly imagined to be in need of civilisation as growing European empires sought to assume racial and cultural superiority over them. Cook, with his ambitions of global expansion, soon became the ideal hero for a country that was in the midst of a full-blown imperial conquest. As the century progressed, the bestiality of Cook’s assailants became emphasised, portrayed to look increasingly like animals, as can be seen for instance in an 1892 illustration of C. R. Low’s edition of Cook’s voyages which concludes the exhibition.

The exhibition will run in the Entrance Hall until Saturday 19 July. A complementary Virtual Exhibition, with additional material not included in the Entrance Hall cases, is accessible on the Library’s exhibitions webpage, and can be viewed here.

Thoroughly enjoyed this blog, thanks! By conicidence, we have just published Wharton’s edition of Cook’s Journal: see http://cambridgelibrarycollection.wordpress.com/2014/06/23/to-new-zealand-and-back-with-captain-cook/