The cyclist as hero: Harry Graf Kessler and private press books

This guest post, written by Dr Jaap Harskamp (formerly Curator of Dutch & Flemish collections at the British Library, who is now working on the University Library’s early Dutch books) celebrates the coming of the Tour de France to Cambridge today. It concerns Harry Graf Kessler and the connections between cycling and private press books.

The Library holds a number of collections of both printed and archival material of typographical interest such as the outstanding Stanley Morrison collection of books and papers, the Broxbourne collection, and others. It also has a considerable collection of printing artefacts associated with private presses (the Golden Cockerel Press, Eragny Press, and Ashendene Press amongst them) – including the punches, matrices and bookbinders’ tools from Harry Kessler’s Cranach Press [1].

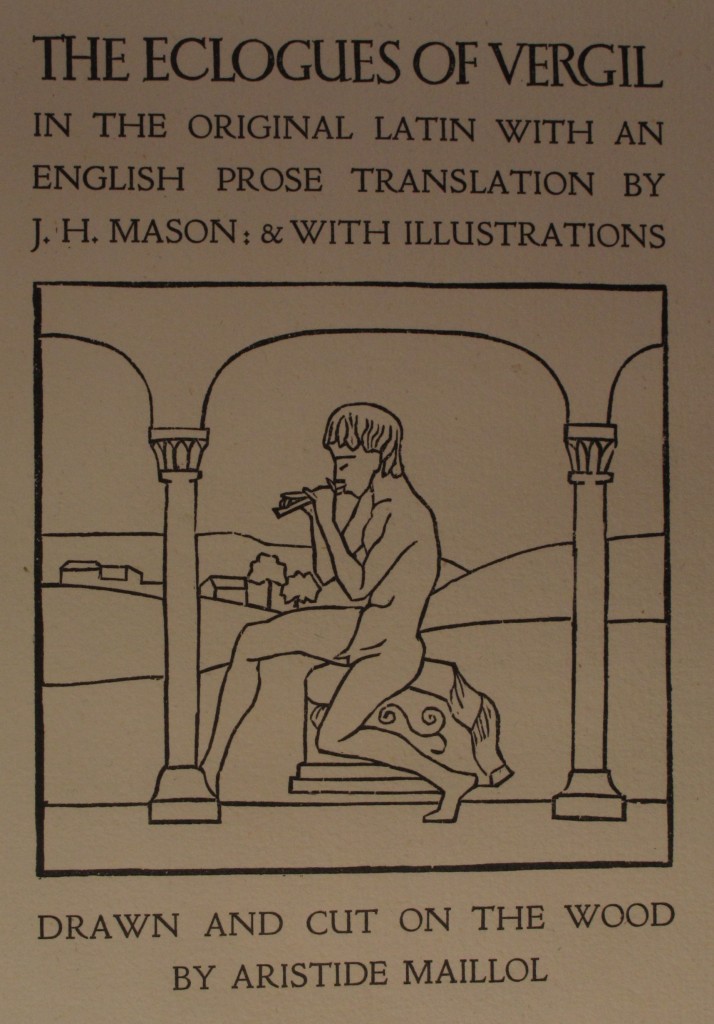

The Eclogues of Vergil, in the original Latin. Edition limited to 264 copies

[Weimar: Cranach Press, 1927], classmark Broxbourne.a.17 (p. [1])

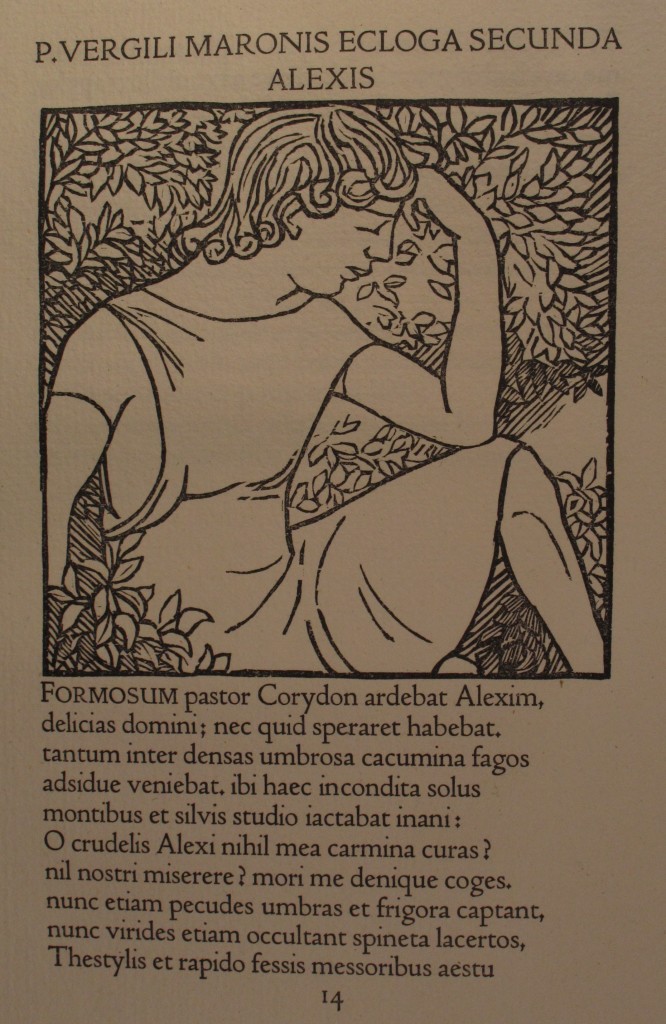

On 20 June 1895, Harry Clemens Ulrich, Graf [Count] von Kessler, paid a first visit to Kelmscott House in Hammersmith. A year later he was back again for further discussions with its owner, William Morris. One of the topics they touched upon was the history of printing. Morris’s views made an impact on his visitor which is echoed in a diary note of 3 May 1898 in which Kessler attacks the lack of style and confusion of taste in contemporary book binding. By 1904, he acted as artistic adviser for the ‘Wilhelm August’ edition of German classics employing English book designers to shape it. The venture represents a landmark in the history of German publishing. In 1913, Kessler founded the Cranach Press in Weimar, the city that had once been home to the German Enlightenment. It was an Anglo-German undertaking. Inspired by the flourishing of English private presses, Kessler achieved publishing distinction by recruiting highly experienced artists and artisans. The Cranach Press produced a few masterpieces including a volume of Virgil’s Éclogues which included the participation of French painter and sculptor Aristide Maillol. This artist had started work on his first major figurine in 1900, a work which was to become known as ‘La Méditerranée’. Its definitive version, exhibited at the influential Salon d’Automne of 1905 (the third in the sequence of these modernist exhibitions), was much admired by Kessler who ordered a marble version of the sculpture. He would become Maillol’s major patron. In 1908 Kessler invited Maillol to join him on a visit to Greece. There the plan was discussed to publish an illustrated edition of Virgil’s first major work. Preparations were interrupted by the war and did not start again until June 1925. The Éclogues was completed in April 1926. The French quarto edition was printed in 250 numbered copies on handmade rag paper with forty-three original woodcuts by Maillol printed in black, and an additional double-suite of woodcuts printed in black and red bound in at the back. The title-page and initials were designed by Eric Gill. A German and an English version in limited editions were issued almost simultaneously.

The Eclogues of Vergil, in the original Latin

[Weimar: Cranach Press, 1927], classmark Broxbourne.a.17 (p. 14)

A true masterpiece is the Cranach edition of Hamlet which consists of a translation of the second quarto of Shakespeare’s play by the celebrated German dramatist Gerhart Hauptmann, surrounded by the relevant source texts of Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus and others.

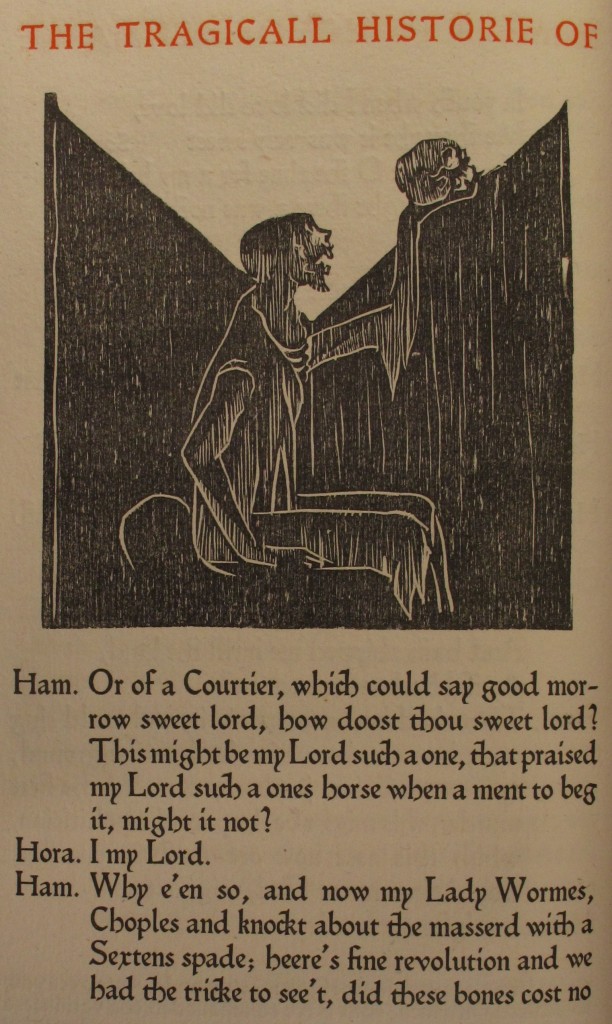

William Shakespeare: The tragedie of Hamlet, prince of Denmarke. Edition limited to 322 copies

Weimar: Cranach Press, 1930 (classmark: F193.a.1.1, p. 146)

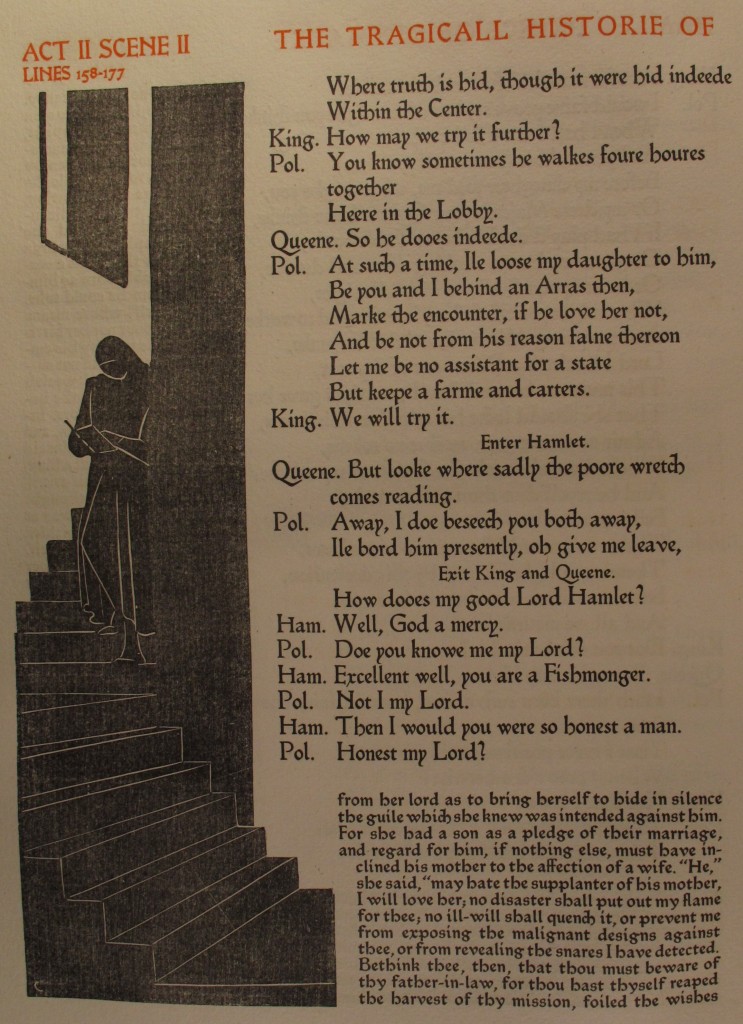

One of the finest books ever produced, it was printed in an edition of 322 copies. Theatre director and stage designer Edward Gordon Craig, son of the renowned Shakespearean actress Ellen Terry, had been working on woodblock illustrations for Hamlet for some considerable time. He created some eighty of the woodcuts for this edition, with one additional contribution by Eric Gill. Kessler would print two grand editions of Hamlet with Craig’s woodcuts, one in German in 1928, and an English version in 1930. The illustrations created powerful images, using black silhouette figures with a few interior white lines to indicate clothes and limbs. The beauty of layout and typography, and the quality of paper, are all in the finest tradition of the book revival of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The paper mill of Montval was run on behalf of the Press by Gaspard Maillol, Aristide’s nephew. The mill produced a range of papers primarily for printmaking and special edition book production. It counted Matisse and Picasso amongst its clients. Kessler secured the support of scholar John Dover Wilson, chief editor of the New Shakespeare, a series of editions of the complete plays published by Cambridge University Press, to edit the work. The typeface, designed by master calligrapher Edward Johnston, was based on the Gothic type used by the partnership of Johann Fust and Peter Schaeffer in their famous 1457 Psalterium (Mainz Psalter). The layout of text and illustration surrounded by commentary mirrors that of early printed books. The Cranach Hamlet is one of the most imaginative works of the twentieth century and a tribute to the stunning beauty of early printed books.

A private press is a small business undertaking for the production and publication of special books – it is at the same time much more than that: printing and publishing is a statement, a world view, an alternative lifestyle. That most certainly applies to the intriguing and larger-than-life figure of Harry Kessler. His father, Adolf von Kessler, was the son of a Protestant clergyman who had married into a distinguished Hamburg banking family. His mother was the beautiful Anglo-Irish Alice Baroness Blosse-Lynch. Young Harry received an international education, first in Paris, then at St George’s boarding school in Ascot, followed by a renowned Hamburg gymnasium and universities in Bonn and Leipzig, where he studied law. Internationalist through birth and education, he chose German citizenship allying himself with the humanist tradition identified with the work of Goethe, Kant and the Von Humboldt brothers. His family moved in the highest of circles. Wilhelm I was attracted to his mother and speculation persisted that the Kaiser was Kessler’s true father (he elevated Adolf to the ranks of the nobility in 1879). Bismarck was another family friend. Upon graduation, Harry joined the Imperial Guard. Called back to his regiment at the outbreak of World War I, he initially served in Belgium, where he experienced the atrocities of war first-hand. Kessler’s life offers a vivid perspective on the dramatic transformation of European art and politics that took place between 1890 and 1930. He was a man of his age. W.H. Auden called him ‘a crown witness of our times’.

William Shakespeare: The tragedie of Hamlet, prince of Denmarke

Weimar: Cranach Press, 1930 (classmark: F193.a.1.1, p. 52)

In the first half of his career Kessler was an ardent champion of German and European aesthetic modernism, becoming a friend and patron to many of the pioneering artists and writers of his day. In his capacity as Director of the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Weimar and Vice-President of the German Artists League, he served as a spokesman for contemporary and experimental art. Kessler was also a member of the German delegation to sign the Treaty of Versailles after World War I. His liberal attitude in politics and art would eventually provoke the rage of the Nazi regime. Popularly referred to as the ‘Red Count’, he showed his courage by co-organizing ‘Das freie Wort’ (Free Speech) congress on 19 February 1933 together with Erich Everth, the first professor to hold the newly created Chair for Journalism (Zeitungskunde) at the University of Leipzig. A few days after the controversial event had taken place, the Reichstag was ablaze. As a liberal democrat and pacifist Kessler was advised to leave Germany for his own safety. Forced into exile and deeply hurt by the barbaric developments he witnessed in the country he had served for so long, Kessler travelled restlessly between Paris, London, and other European destinations. In 1937, impoverished and alone, he fell ill and died in Pontanevaux, a village in the Burgundy region. Kessler lies buried in the family vault at Cimetière du Père Lachaise in Paris where he is surrounded by many of the artists he had stimulated or sponsored in life.

It was known that Kessler had kept a diary since a youngster until his death in 1937. For decades, the earlier part was presumed lost. However, in 1983, on the island of Mallorca (the author lived for a number of years in Palma de Mallorca), a safe-deposit box was retrieved containing Kessler’s journals and correspondence, along with newspaper clippings and photographs. The valuable contents was transported to Marbach am Neckar, birthplace of Friedrich Schiller, and the location where the German Literature Archive (Deutsches Literaturarchiv) is kept. Kessler was a compulsive diarist: the first entry was written on 16 June 1880 when he was twelve years of age, and the last on 30 September 1937, two months before his death. The German edition of the diary runs to nine volumes. It provides a personal insight into the ‘belle époque’ and early twentieth century and includes the observations he made during a trip around the world in 1892 with lively descriptions of street life New York and colourful impressions of Tokyo. The diary is on a par with the private records held by Samuel Pepys, Henri-Frédéric Amiel, the Goncourt brothers, or André Gide. Harry Kessler was intimate with high society in Germany, England, France and Italy. He rarely missed the premiere of an important cultural production in whatever European capital, whether it was work by Sergei Eisenstein, Claude Debussy, Bertolt Brecht, Gabriele d’Annunzio or Luigi Pirandello. He left memorable portraits of poet Paul Verlaine in old age, of Degas and Renoir, of Rodin and Maillol, of Augustus John and John Singer Sargent, of Rilke, Cocteau and Gide, of Richard Strauss, Ravel and Stravinsky, of Sarah Bernardt and Isadora Duncan, of Diaghilev and Nijinsky, of David Lloyd George and Albert Einstein. We see him assisting Hugo von Hofmannsthal to work out the plot of Der Rosenkavalier (the libretto is dedicated to him). He was co-founder of the luxurious avant-garde art and literary magazine Pan which was published in Berlin between 1895 and 1900 and edited by Otto Julius Bierbaum and Julius Meier-Graefe. He was close to Elizabeth Nietzsche, the philosopher’s notorious sister. When she informed him that Friedrich was dying, he travelled to Weimar and left a moving description of Nietzsche’s final hours. Harry Kessler was a cosmopolitan mind, a representative of that great European inquisitive and creative spirit that was being destroyed under his own eyes [2].

L’éphebè – a bronze sculpture of Gaston Colin, by Aristide Maillol

(Photo courtesy of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

Kessler’s ideal of beauty was male. It was men bathing naked in rivers. It was working-class boys fighting in a Whitechapel boxing ring (‘East End and Greece in one’, he noted in his diary on 25 April 1903). It was the attraction of two young Belgian sailors on leave, or Nijinsky performing on stage. By 1907 he was in an amorous relationship with a slender seventeen year old racing cyclist named Gaston Colin. The Kessler archive in Marbach holds a number of notes (so-called ‘petits bleus’) sent from Colin to his lover from various stages of the Tour de France. Having met Aristide Maillol for the first time on Sunday 21 August 1904, Kessler came to consider the sculptor’s work the embodiment of excellence. He was attracted to the sensuality of his art. On 10 November 1902 he had noted in his diary that the great loss for art since the Renaissance was the disappearance of warm-blooded lust. To Kessler, the naked body and the beautiful human face were the alpha and omega of great art. However, it took him a great deal of effort encouraging the firmly heterosexual sculptor to chisel a male nude. He finally persuaded him to have Gaston Colin stand as his first adult male model. Maillol executed the sculpture in 1908 in his studio in Marly. When the clay version was finished, Kessler ordered a bronze cast to be made. In his diary the latter documented the progress of the work and took a number of photographs of a nude Colin posing in Maillol’s studio. The statue of this adolescent male became known as ‘Le coureur cycliste’ (but without his bike) [3]. It is the sculptor’s only major free-standing male nude. With the acquisition of this sculpture in bronze Kessler came to possess a full-length nude portrait of his lover and companion, an image of physical perfection. However, critics considered its realism disconcerting. To many of them it seemed a shameless celebration of the penis. Even Kessler found its features somewhat exaggerated.

Young Colin was a keen cyclist. From the end of August and throughout most of September 1907, he and Kessler went on a bicycling tour of Normandy and the Channel Islands. Colin’s participation in the Tour de France however seems improbable. It is doubtful that this young adolescent would have had the brute strength to take part in a race that was then and remains now one of the most gruesome of enduring sports. The fifth annual Tour of 1907 (won by Lucien Petit-Breton) took place from July 8 to August 4 and attracted ninety-three starters of which thirty-three made it to the line as classified finishers in Paris. The name of Gaston Colin is not amongst them. For 1908 the same applies. From letters written to Kessler in 1908/09 there is evidence that Colin took part in bicycle races in France, Italy and Spain, not as a competitor however, but most likely as a mechanic (with the outbreak of World Word I he served as a mechanic in the 36th Artillery Regiment at Moulins). Whatever Colin’s involvement in the Tour may have been, Maillol produced the first known statue of a racing cyclist. In the end, he produced only three male nudes: apart from the cyclist, there are those of an ‘Athlete’ and a ‘Dying Warrior’. The link between sport and war is significant.

The glorification of physical strength was a theme of the times. Sport played an important part in the emergence of both socialist and fascist thinking in Europe. In Germany, Charles Darwin’s theory made an impact immediately after publication of On the Origin of Species in November 1859. A first translation by palaeontologist Heinrich Georg Bronn appeared in April 1860 [4]. Politicians were attracted to the socio-economic directions Darwin seemed to indicate. In 1899, socialist Ludwig Woltmann introduced the notion of social Darwinism into the academic jargon. The theory of evolution gave rise to a new set of norms. Health (fitness) and sickness (unfitness) became criteria for making ethical judgements. Whatever lifts man to a higher state of mental or physical being is moral. Sport and the building of sport stadiums were part of a drive for regeneration. In his adoration of athletes (he subscribed to Pierre de Coubertin’s Olympic ideal from which women were banned), Kessler showed his Anglo-German background. The military of the British Empire patronized sport because competition enhanced fitness, boosted morale, provided a physical outlet, and countered boredom. Motivated by anxieties about perceived physical deterioration of the young, English educationalists represented the strengthening of male bodies as a duty of patriotic citizenship. Public schools with their emphasis on character, manliness and sport, embodied the essence of the imperial ethic. There was a strong belief that the best proof of a man’s fitness to rule India was to have been Captain of Games at school. Kessler would have experienced the teaching of this spirit during his (happy) school days at Ascot. This odd mixture of cycling, cosmopolitanism, social Darwinism, Greece and homoeroticism, determined Harry Kessler’s aesthetics and his vision as a book designer.

By Dr Jaap Harskamp

References

[1] The Library Department of Manuscripts holds seven boxes of ‘Edward Johnston papers on his type-designs for the Cranach Press (GBR/0012/MS Add.9818). These papers also cover Stanley Morrison’s purchase of the punches for Johnston’s Cranach Press types in 1945 and their conveyance to Cambridge University Press some five years later.

[2] Das Tagebuch 1880-1937 / Harry Graf Kessler; herausgegeben von Roland S. Kamzelak und Ulrich Ott ; unter Beratung von Hans-Ulrich Simon, Werner Volke und Bernhard Zeller. Stuttgart: Cotta, c. 2004. Classmark: 746:01.c.12.51-58.

Also:

Harry Graf Kessler: Journey to the Abyss: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler, 1880-1918 / edited, translated, and with an introduction by Laird M. Easton. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011. Classmark: 571:62.c.201.6.

[3] http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/works-in-focus/sculpture/commentaire_id/the-cyclist-3188.html?tx_commentaire_pi1[pidLi]=842&tx_commentaire_pi1[from]=729&cHash=53c06d39bb

[4] Charles Darwin: Über die Entstehung der Arten im Thier- und Pflanzen-Reich durch natürliche Züchtung, oder, Erhaltung der vervollkommneten Rassen im Kampfe um’s Daseyn / nach der zweiten Auflage … aus dem Englischen übersetzt und mit Anmerkungen versehen von H.G. Bronn. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart, 1860. Classmark: Item no. 1 in volume 8001.c.14.

Pingback: The cyclist as hero: Harry Graf Kessler and private press books (Special Collections blog) | European languages across borders