‘The necklace of her kingdom’: Elizabeth I and Cambridge

In August 1564 – 450 years ago this month – Queen Elizabeth I visited Cambridge for the first time during her reign. The town was spruced up for the occasion, with scented flowers strewn on the ground and flags hung from buildings. Her arrival on Saturday 5th August was received with trumpet fanfares and the pealing of church bells (though Great St Mary’s was fined for neglecting to ring). The current Entrance Hall exhibition commemorates the visit, bringing together manuscript and printed material relating to the event and to the Queen’s connections with the University. On Saturday 5th August The Queen was welcomed into King’s College, her home for the visit, with a Latin oration and on the Sunday evening, Plautus’ Aulularia was performed by torchlight in King’s chapel, with two more plays following on Monday and Tuesday. The Queen rode her horse through the town on Wednesday, visiting the colleges and receiving more gifts and celebratory orations. This was evidently something of an ordeal, for the day was a hot one and Jesus and Magdalene colleges had to be dropped from the schedule. At Trinity, founded by her father, progress on the new chapel was inspected, and at St John’s the Queen rode right into the hall. The day was rounded off with disputations in law and divinity at Great St Mary’s, after which the Queen was invited to reply to the University in Latin, her initial embarrassment giving way to four hundred words of Latin, to the great delight of all present.

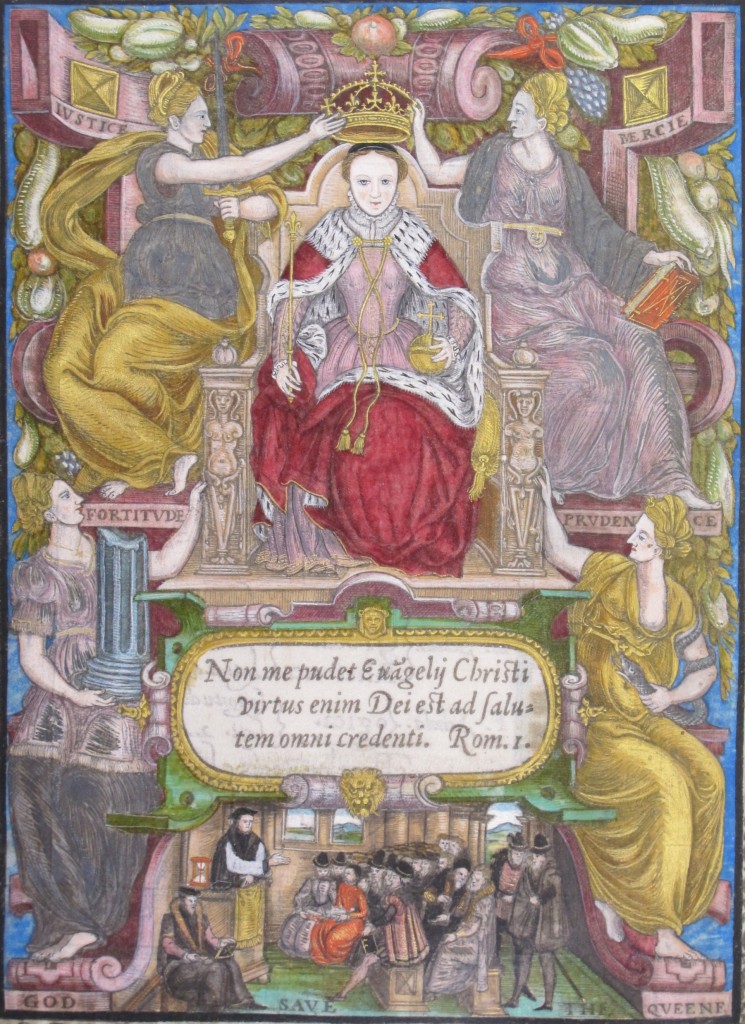

Portrait of Elizabeth I inside a copy of Matthew Parker’s Catalogus cancellarioru[m]… (London: 1572 – Sel.3.229)

The Queen called the colleges of the University “the necklace of her kingdom” and pointed to her great desire to found a college herself. Although it was her first visit, the Queen must have felt some familial ties to the University. She was presented with a pair of gloves at Christ’s College in memory of her great-grandmother (Lady Margaret Beaufort, the founder of the college and of St John’s) and in King’s College chapel visual reminders of her parents were everywhere. Her father finished the chapel and commissioned the magnificent Italianate wooden screen to celebrate his marriage to her mother, Anne Boleyn, whose symbol, the falcon, is carved into it, along with the initials HA, for Henry and Anne. Although she would never return to Cambridge, the University never forgot the visit and, at the close of the first Elizabethan age in 1603, members compiled a book of verses lamenting the passing of Gloriana.

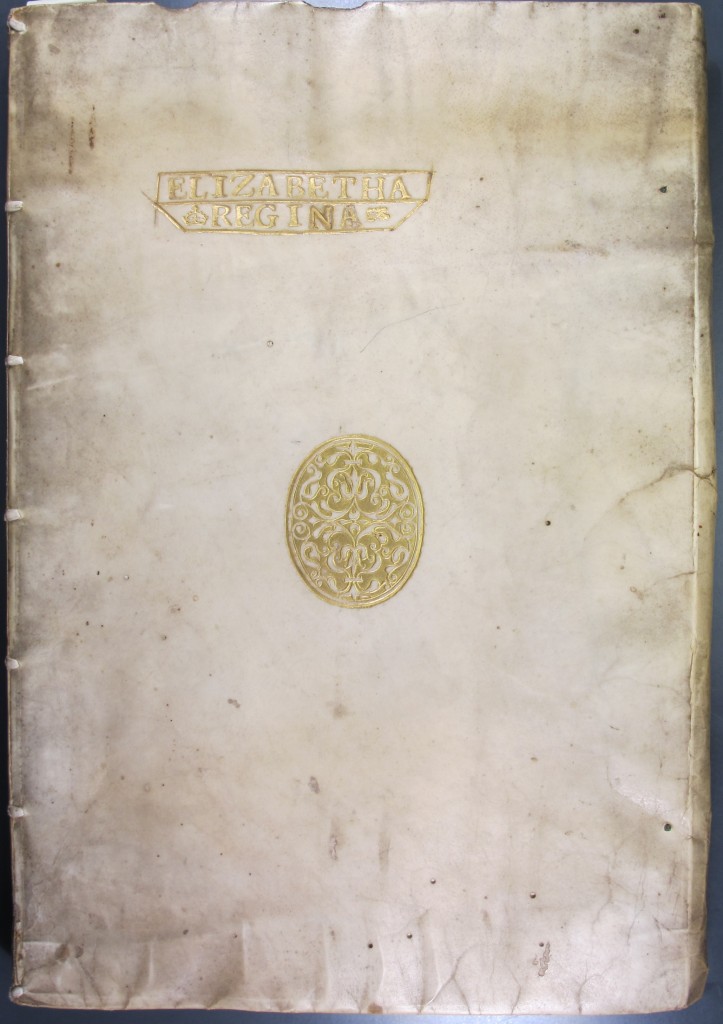

The most remarkable volume to survive from the visit is a collection of verses penned by members of the University to celebrate the event. Its compilation was suggested by the Bishop of London about three weeks before the Queen’s arrival, so its production was somewhat hurried, with loose sheets of paper sent out to each college which were then gathered up and bound together in cheap limp vellum.

It contains over 300 verses praising the Queen, composed in Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Latin and English, by members of eleven of the fourteen colleges in existence at the time (King’s College presented its verses in a separate volume and Trinity Hall and Magdalene abstained). Such verses reinforced the bonds between the universities and the state, as did the honorary degrees conferred upon members of the Court. The compilation, verses from which were read out at the appropriate college or set up at various places in the town, initiated a tradition of congratulatory verses at Cambridge which lasted for two centuries. At Christ’s College over a third of resident members took up their pens, reflecting the importance the college placed on the teaching of rhetoric. During the visit, Sir William Cecil (Chancellor of the University) “caried the books in his owne handes and at everye colledge perused the same.” The volume was to be presented to the Queen at the end of the visit but (perhaps due to her preference for velvet over vellum bindings) it remained in Cecil’s hands and was kept at Burghley House until 1687. After passing through several private collections it was bought by the bookseller Quaritch in 1991 and sold by Sotheby’s in 1992. The volume was purchased by the University Library, with contributions from the colleges who had originally contributed to its production.

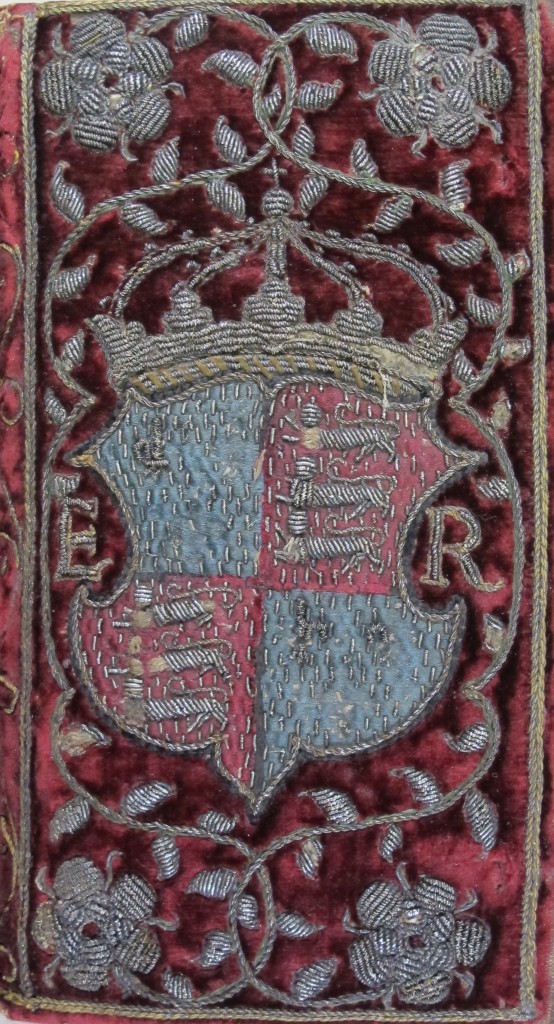

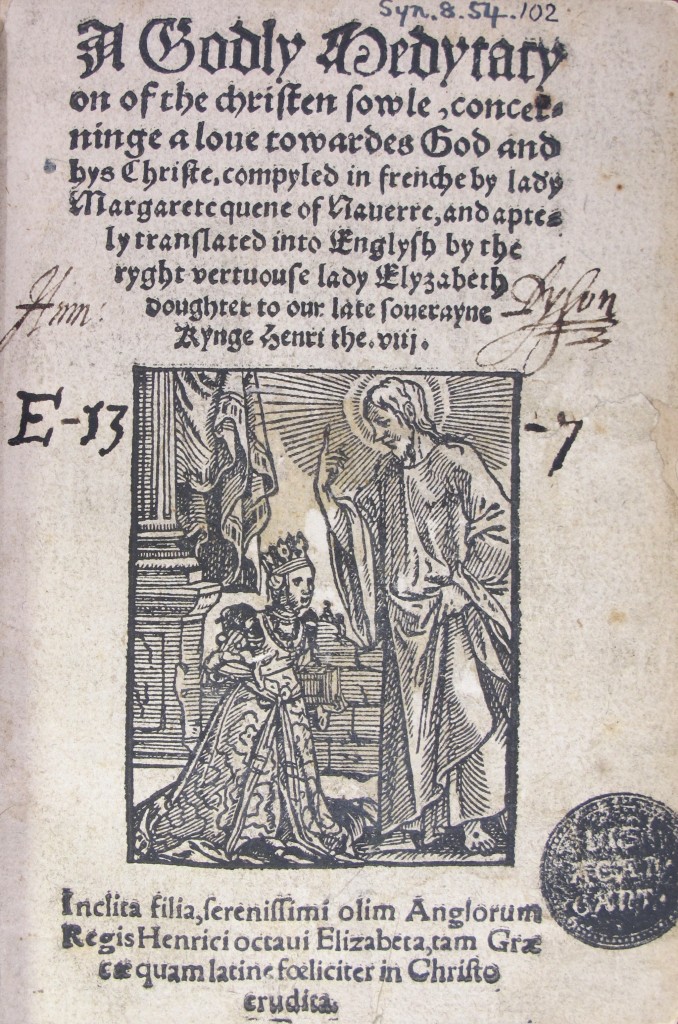

Other items of interest in the exhibition include a delicately embroidered velvet binding, which covers a copy of John Udall’s Sermons (London: 1596). Udall was educated at Christ’s and Trinity Colleges and took his MA in 1584. His Diotrephes of 1588 denounced the Church of England and in the same year he supplied material to John Penry, author of the Marprelate tracts. All this led to his arrest and trial, at which he was sentenced to death, before being pardoned by the Queen. This copy of his sermons is a precious survival, in its contemporary velvet binding – a style much favoured by the Queen – with silver and silk embroidery and the arms of Elizabeth I. The presence of the Royal arms does not indicate Royal ownership, but rather the influence of the insignia on contemporary design. It came to the library with the bequest of Samuel Sandars in 1894. According to a note inside he purchased it for £5 in 1887 “through one of the shopmen of Mr Johnson of Cambridge who told me a poor friend of his had a curious book to dispose of.” Other works relating more broadly to Elizabeth’s literary world include a copy of the English translation of Marguerite of Navarre’s Miroir de l’âme pécherresse (Mirror of the sinful soul), translated by a young Princess Elizabeth. This mystical narrative of the soul, possibly inspired by the death (on Christmas Day) of Marguerite’s only son, was first published in Alençon in 1531. Aged just 11, Elizabeth translated the work into English as a New-Year’s gift for her step-mother Katherine Parr and the original manuscript, which retains its Elizabethan embroidered binding (possibly executed by Elizabeth herself) is preserved in the Bodleian Library. The first printed edition was edited with a preface by the churchman John Bale (a student of Jesus College) and the German publisher Dirk van der Straten produced a small number of similar devotional works as well as being co-publisher of the first edition of Bale’s Illustrium maioris Britanniae scriptorium. This copy belonged to the scrivener and book collector Humphrey Dyson (1582–1633) who inscribed his name on the title page, and it entered the library before 1715.

The exhibition will run until Monday 15th September, in the Entrance Hall cases, accessible 9.00-6.00 Monday-Friday and 9.00-4.30 on Saturdays.

Please contact Liam Sims (ls457@cam.ac.uk) for more information.