Early Egyptian texts revealed; the papers of Sir Herbert Thompson

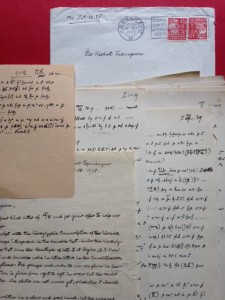

The University Library has recently acquired from the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, an archive of the personal papers of Sir Herbert Thompson, the Egyptologist and specialist in ancient Egyptian languages. He was also the founder of the Cambridge Chair of Egyptology which is named after him. The archive is an extensive collection containing notes for his publications, notes on language and correspondence with other Egyptologists. At present the archive remains unsorted but is likely to shed a great deal of light on Thompson’s work and on the development of Egyptology studies in the UK in the early part of the twentieth century.

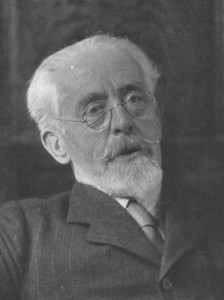

To briefly describe the early part of his life; Herbert Thompson was born in 1859, the son of Henry Thompson, Baronet, a distinguished surgeon who studied at University College, London and became a surgeon at University College Hospital. Herbert, his only son, was educated at Marlborough and Trinity College Cambridge after which his private income enabled him some freedom to choose his career. Initially he took up a legal career but he failed to find any long-term satisfaction in the work. At his father’s suggestion he then took up the study of biology and medical research at University College, but again there were problems as the constant use of the microscope strained his eyesight and this venture also came to an end. During this time, though, he met the eminent archaeologist Flinders Petrie who, in a visit to the laboratory, asked Thompson for a report on some skeletal remains from Egypt. Thompson, perhaps caught up by Petrie’s enthusiasm and charisma, became absorbed into the world of Egyptology and so, at the age of forty, his interest in the subject took hold and was to last for the remainder of his life.

To understand how Thompson fitted into the larger picture of Egyptology at the time, a brief description of the background could be useful here. The study of Egyptology in British universities lagged behind its development in European countries, but a great step forward was made when Amelia Edwards (1831-92) the staunch supporter of Egyptian study and exploration, donated her collection of Egyptian antiquities and her library to University College London where they became the founding collections of a teaching department. She also bequeathed sufficient financial support to fund the Edwards Professorship of Egyptian Archaeology. Her great friend and protégé was Flinders Petrie, the renowned excavator of Egyptian sites, and he was the first holder of the Edwards professorship. He also brought his own expertise and antiquities collections into the Department. Amelia Edwards also founded The Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF) in London in 1882, an organization created in order to examine and excavate in the areas of Egypt, later known as the Egypt Exploration Society. The intent was to study and analyze the results of the excavations and publish the information for the scholarly world.

This was the backdrop of Egyptology studies by the time Thompson came into contact with the subject. Studies at UCL, directed by Petrie, had attracted an impressive group of gifted scholars, including both archaeologists and specialists in ancient Egyptian languages. Initially, Thompson studied a general grounding in Egyptology but then made language studies his speciality. He formed part of a close-knit group working on ancient Egyptian texts which included F.L. Griffith, the Demotic specialist (the first Egyptologist to hold a post at Oxford and whose bequest founded the Griffith Institute there) and Walter Crum the Coptic scholar. Both of these were pre-eminent in their fields of study. Demotic and Coptic were both languages which had developed out of the ancient languages of Egypt, written in hieroglyphs, via its more cursive hieratic form. Coptic was written in the Greek script with some additional characters taken from Demotic. Thompson himself by his skill and dedication became a foremost scholar of his generation specialising in both Demotic and Coptic and lecturing at UCL in 1915-16.

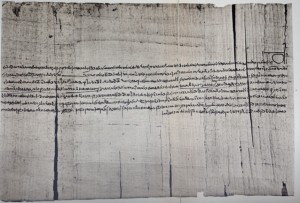

Subsequently, Thompson worked on the Demotic papyri in the British Museum and, published The Demotic magical papyrus of London and Leiden with E.L. Griffith in 1904-9. With Walter Crum, he worked on the publication of Crum’s Coptic dictionary (1929-39). He also assisted Petrie by writing chapters in his excavation report Gizeh and Rifeh (1907). Thompson continued to publish for the next forty years producing a notable collection of Coptic and Demotic texts the most important of which is his A Family Archive from Siut (1934) which is now recognized as a classic of scholarship and a major contribution to Demotic studies in ancient Egypt; the texts tell of a complicated family history concerning marriage and property and including the original text of a trial. Thompson also made a valuable preliminary study on the Coptic writings of Mani, part of which was later published by the Cambridge Manichaeian scholar Charles Allberry.

Thompson himself made only one visit to Egypt, an extended visit to Saqqara with J.E. Quibell, a pupil of Petrie, and after which he edited the Coptic inscriptions in Quibell’s publication about his excavations there in Excavations of Saqqara, 1908-9, 1909-10; the Monastery of Apa Jeremias (1912). Later in his life, even after he would have preferred to retire to his home in the country at Apsley Guise in Bedfordshire, his expertise and advice was called upon by many others who were studying and publishing in these fields. He was said to be a reticent man but generous in helping others; there can have been few students working on Coptic and Demotic who do not owe something to Thompson in terms of consultation and advice.

As well as his academic achievements, Thompson was a generous supporter of Egyptology in many other ways both financial and practical. He was a great financial supporter of archaeological excavations and he also donated the greater part of his personal Egyptology library to the Egypt Exploration Society in 1919. His Egyptian language books he donated to Cambridge where they formed a teaching library for Egyptology students situated first in the Old Press Building in Trumpington Street, then in Downing Place and then it became part of the Faculty of Oriental Studies (now FAMES) Library on its move to the Sidgwick site in 1968. The archive in all probability followed a similar route but its recent transfer here, in two consignments in 2012 and 2014, takes advantage of the cataloguing and reading room facilities for archives provided here; some of the papers are already listed in the Janus Catalogue. The archive is also reunited with the collection of Demotic ostraca, formerly belonging to Thompson which came to CUL between 1911 and 1916. Also in CUL, the archive joins the papers of other eminent Cambridge scholars in Ancient Near Eastern studies which is gradually increasing in significance.

Thompson had succeeded to the baronetcy in 1904 on the death of his father, but did not marry or have children himself, so he was free to use his fortune to secure the future study of Egyptology. Perhaps Thompson’s most significant contribution to Cambridge was the endowment of a post for Egyptology founded in 1946 and the first incumbent being the distinguished Egyptologist Sir Stephen Glanville, a pupil of Petrie and of Thompson, who became not only Cambridge’s first Professor of Egyptology (1946- 56) but also became the Provost of King’ College (1954-56).

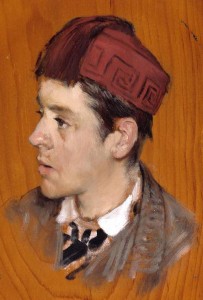

Thompson was said to be a modest and unassuming man and apart from serving on the Committee of the Egypt Exploration Society he took little formal part or position at either UCL or in the EES. He also had a deep interest in the Classics and the arts, travelling widely in Europe, especially Italy. The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has a small collection of early Italian paintings and a larger collection of prints which he donated. There are also two portraits of him in the Museum’s collection painted of him as a young man by his friend Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema in 1877 and 1878.

Herbert Thompson died in 1944 at his home in Bath, but during his lifetime he had made a significant contribution of Egyptology both with his own publications and as an adviser to others. From his private fortune he was able to support the subject financially and in his generous donations of books he was able to help library collections. His archives will also, as they are sorted and catalogued, will reveal more about this reticent but distinguished scholar who plainly had a passion for the subject which he decided to make his own.