Collectors: John Couch Adams, a reminder about the Rose Book-Collecting Prize, and a beautiful binding.

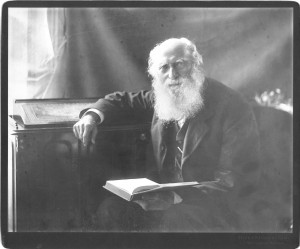

John Couch Adams, the collector.

It is this time of the year when Cambridge University Library advertised this year’s competition for the 2015 Rose Book-Collecting Prize [entries due no later than Tuesday 13th January], which offers students the chance to win £500 by building their own book collections. It is advised that “the judges will make their decision based on the intelligence and originality of the collection, its coherence […], as well as the thought, creativity and persistence demonstrated by the collector and the condition of the books. The monetary value of the collections will not be a factor in determining the winning entry…”. Last year we illustrated these qualities with a description of Samuel Sandars as a collector. This year will highlight his contemporary John Couch Adams, a great astronomer and surprising books collector. Both collections were bequeathed to the University Library in the 1890s, and both were built by proud Cambridge alumni, but they both illustrate different aspects of the qualities enumerated above.

If John Couch Adams is relatively well-known and remembered today, it is in his capacity of astronomer and discoverer of the planet Neptune; his life as a book-lover has not really been studied. John Couch Adams was born in Cornwall in 1819, in a devoted Wesleyan family with a great belief in education. His father, Thomas Adams, was a tenant farmer. Adams was an outstanding student and graduated as a Senior Wrangler in 1843 and became President of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1851. In 1860, he was appointed director of the Cambridge Observatory, a post he would hold until his death in 1892. In spite of such academic and professional credence, Adams’ modesty seems to have been a remarkable feature of his character. He refused a knighthood in 1847 and later declined the office of Astronomer-Royal; his modesty and lack of interest in honours is also apparent in his collecting habit in the fact that he did not have a bookplate made during his lifetime. A recognised but unassuming scientist, John Couch Adams had also a life-long passion: books and knowledge.

Photograph of John Couch Adams (1819-1892), taken circa 1888 by Olive and Katharine Edis, photographers of Sheringham, Norfolk. Image courtesy of the Institute of Astronomy Library.

Throughout the years, as can be seen from his unpublished diaries, kept at St John’ College Library, Adams appears to by a compulsive buyer of books, calling at booksellers each time he went to London, perusing catalogues, ordering several times a week, cleaning and having the books bound if necessary or returning them. For instance, the entries for the beginning of January 1881 record: “Going to London, Buying two books, looking in at Ridler’s [this is William Ridler (fl. 1877-1904) a bookseller provider of incunabula, at 45 Booksellers’ Row on The Strand, in London]; on Monday 3: “Drove to Ash[?] for some books, […] then called at Ridler’s and bought some books and came down to Cambridge.” On Tuesday 4 he “Left by 10 train. Went off to Ridler’s, returned a book and bought some more.” The diaries show a man of varied interests, keen on educating himself, reading the classics and borrowing books from his college and the UL. They do not, however, paint the picture of a bibliomaniac, a man obsessed by beautiful objects – nor do they paint the picture of a bibliophile specialising in the history of books, but rather evoke an avid reader, keen to learn about as many subjects as possible. He had contact with a great many booksellers, but does not seem to have been much in touch with those favoured by the book-hunters, such as Bernard Quaritch; he did not keep any significant correspondence with either booksellers or librarians that is known of. Unlike Sandars, Adams did not correspond with the successive University Librarians. As far as we can tell from his correspondence, Francis Jenkinson, Head of the Library at the time of Adams’ death, appeared surprised and impressed by what he discovered in Adams’ library.

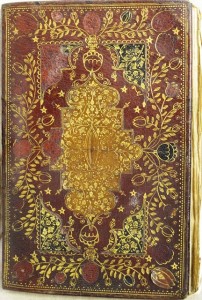

Indeed, in his long collecting life, Adams had acquired some rare and treasured books. There are all in all few bindings of note in the collections, but one of the most notable is Adams.7.67.14, with a binding by Samuel Mearne, (1624 – 1683), the celebrated English restoration bookbinder, who whith his sons, Charles and Samuel Jr., were one of the group referred to as the Queen’s binder. This binding was quite famous and fashionable at the time: the Anglo-Saxon Review for Lady Randolph Churchill’s Quarterly guinea magazine , which reproduced varying bindings in morocco after celebrated originals, used it for one of its issue. Adams could not help but sometimes succumb to the prevailing market for early-printed treasures, such as “his Caxton”; he recorded, on 9 May 1881: “Called at several bookshops [when in London] – v. extravagant – bought a Caxton.” (This was presumably The Golden legend (1498) Westminster: Wynkyn de Worde, 8 Jan. 1498, now Adams.4.49.4). About six months before, on Monday 8 November 1880, he stated in his diary: “Found out by referring to Lalande [Jerome de Lalande 1732-1807 French astronomer and writer] that the Celestial Atlas (now Adams.7.83.5) is […] a great rarity.” But he was discreet and unassuming about it; hence maybe Jenkinson’s surprise at finding incunabula amongst the books of someone he considered, first and foremost, a shy astronomer.

A description of the John Couch Adams collection will be posted in our collections directory in the new year. Recent discoveries about the provenance of Adams’ books will also be posted soon on this blog. So watch this space, and meanwhile, enjoy the festive season while comtemplating the beautiful Mearne binding of the Book of Common Prayer…

Pingback: Collecting Texts | Magdalene College Libraries