Changi civilian internment digitisation project

The Royal Commonwealth Society Collection is delighted to announce that work has begun on its project to conserve and digitize the archives of two Second World War civilian internment camps on Singapore, generously funded by a Research Resources Award from the Wellcome Trust. At the conclusion of the project in Aug. 2017, the records of the Changi and Sime Road Camps will be made freely available via the Cambridge Digital Library. They will be of immense interest to the families of internees, academic researchers, students and the general public, since few survivors ever spoke of their traumatic ordeal. The first stage of the project involves the meticulous conservation of the archive, and my colleagues from the Conservation Department, Emma Nichols and Mary French, will shortly be posting about their work.

At this stage, it may be helpful to provide a little historical background and brief introduction to the archive. With the outbreak of the Second World War, British colonial civil servants were expected to remain at their posts, and civilians running businesses overseas were asked to stay to support the war effort. In this respect British Malaya’s rubber and tin industries were particularly important. There were plans to evacuate women and children from Malaya to Australia, but the speed of the Japanese invasion in December 1941 caught many by surprise. There was an exodus of refugees to Singapore as the Japanese advance continued. Memoirs in the collection vividly record the final battle for Singapore: aerial bombardment, the shelling of the city, brightly blazing petrol stores in the harbour and the acrid smoke of burning fuel.

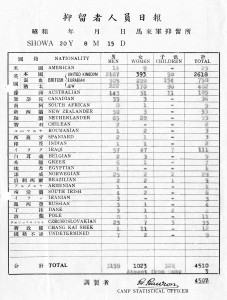

On 17 February 1942, three days after the official surrender of Singapore, all British civilians of European descent were required to report to the Padang. After temporary accommodation, on 6 March they were marched to Changi Goal, a grim concrete building in the eastern part of the city, completed in 1936. Although built to house 600 inmates, approximately 2,500 civilians were eventually confined there. Internees were separated by gender. No contact between husbands and wives was permitted for the first 15 months of internment, with extremely limited opportunities thereafter. In May 1944, civilian internees were moved out of Changi to a camp at Sime Road, to make way for POWs who had survived constructing the Burma Railway. Approximately 1,100 more people were interned at this time. Although Britons comprised the great majority, the final roll call of internees from Aug. 1945 includes the citizens of more than twenty countries, emphasising the international significance of the collection.

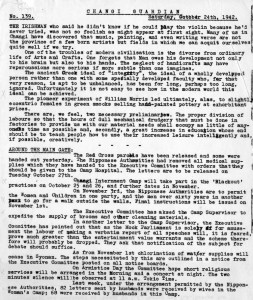

The archives help us vividly to reconstruct the lives of Singapore’s civilian internees. They include official records compiled by the camps’ internal administration. Nominal rolls document personal data: an internee’s name, date entered camp, marital status, occupation, age, nationality, and camp address, and were arranged in three parts – men, women and children. Other sources shed light upon accommodation, camp discipline, relations with the Japanese authorities, work parties, diet, health and hygiene, recreation and leisure, the delivery of mail, and the repatriation of internees at the end of the war. Newspapers circulated within the male camp, such as the ‘Changi Guardian’, reported upon events, disseminated news of sporting, musical and theatrical societies, and published fiction, poetry and humour. These official records are complemented by the correspondence, diaries and memoirs of individual internees – very poignant personal accounts of the psychological and emotional experience of internment.

The survival of this unique archive is largely due to the vision and determination of Hugh Patterson Bryson (1898-1977), a career member of the Malayan Civil Service, who himself had been interned in Changi. From 1952 to 1967 he served as Secretary of the British Association of Malaysia and Singapore. Bryson was deeply committed to preserving the history of the two countries, collecting original documents from association members, and encouraging them to write memoirs, many of which were published in its journal. The records relating to the history of the Second World War in Malaya form the largest section of the BAM archive. Bryson’s insightful notes on the provenance of individual items and correspondence with donors and authors provide invaluable assistance in interpreting the collections.

As noted above, the Changi digital archive will be published in Aug. 2017. There will be no access to the original material while it is being conserved and photographed, but a microfilm copy is available for consultation in the Manuscripts Reading Room.

Pingback: Conservation Challenges posed by the Changi Archive | Cambridge University Library Special Collections

Pingback: Changi digitisation project at Cambridge University Library | Southeast Asia Library Group (SEALG)

A great initiative and worthy of all the time spent in preserving these records. Over 20 nationalities were imprisoned and this project will be of world wide interest.

Is there a way of getting updates of progress?

Dad, Desmond Bettany, was a POW in Changi Jail for 2.5 years and painted to keep sane. We found over 300 paintings, often the opposite to his reality to keep him sane, that had been in his cupboard for 70 years. They are now available to the world to view on http://www.changipowart.com

Dear Keith,

Very many thanks for your support for our project to digitise the Changi civilian internment records. We will be posting regular reports of progress on the Special Collections blog. Many thanks too for sharing your father’s remarkable story.

All the best,

John

Pingback: Christmas in Changi | Cambridge University Library Special Collections

My mother, Winifred Pestana was interned at Sime Road as she was the wife of a POW, Noel Pestana who was sent to the Siam-Burma Railway. Thank God both survived their ordeals and so I am keenly looking forward to accessing this wonderful repository! Congratulations!!

My Great Aunt Annie De Cruz died in Dec 1944 & was buried in Bidadari cemetery. I was told she died in Changi but I believe all civilians were moved to Sime Road. I have nor been able to find any record to confirm this so look forward to the project being completed.

Pingback: The History and Conservation of the John Weekley Changi Archives | Cambridge University Library Special Collections

Pingback: Update from the Changi Digitisation Project, Cambridge | Southeast Asia Library Group (SEALG)

Pingback: Under the Microscope – Preliminary Investigations of the Changi Archive Conservation Research Project | Cambridge University Library Special Collections

I shall welcome the opportunity to look at the archives when they are available. Is there any way that you can let me know by email when the archives are available for viewing?

We are unable to contact individuals, but please follow the Special Collections blog for information about the launch of the digital archive in Aug. 2017.

I’m very glad the collection is being digitised. I spent several days at Cambridge Library searching through the BAM archive but it was too much information to cover in such limited time available.

Hugh Patterson Bryson, mentioned above, was from Portadown, Northern Ireland. He was in the Tank Regiment during the First World War and received the Croix de Guerre and the Military Cross. His page on the IWM’s Lives of the First World War is https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/lifestory/577595 . I’m still updating it.

It just happens that I’m from Hugh Bryson’s hometown and came across this information during research on the Irish in Singapore and the Singapore Cenotaph. I’m sure there were many other internees who went through the First World War. So far I have the details of two others, both Irish because of the overlap in my areas of research.

My father, Leslie Fielding Wilkinson, born in Ireland on 17 August 1903, worked in Malaya from about 1927 in Telecoms. During the war he was in Changi and/or Sime Road. He returned to Malaya after the war, and retired to Ireland in 1953 having been Director General of Telecoms.

In the Imperial War Museum Changi list he is recorded as British, and had a British passport as was the case with Irish nationals back then.

I am visiting Malaysia and Singapore in January 2018 and am very interested to find out more about my fathers time in Changi/Sime Road.

we have a relative that died in changi in september 1943, i was hoping to find out where he would have been buried ? can you help me with that

Pingback: Farewell to Changi – Cambridge University Library Special Collections

My granddad Savege C.R. a civil engineer was imprisoned at Changi. Recently, while going through his papers I found a letter from King George welcoming him home and also a copy of the DOUBLE TENTH investigation. Through your site I understand what it is all about. many thanks

Following the death of my mother a couple of years ago,I am now going through my grandfathers papers and diaries from his time as a civilian internee. I’m currently transcribing them for our family interest but wondered if there was anywhere they should be stored, or do you have so much information you don’t need any more?

My grandfather was a rubber plantation manager, aged 55 years upon internment.

Hello Sue, my grandfather, Henry Antony Mervyn Parry, was also a rubber plantation manager in Malaya and was imprisoned in Changi civilian gaol at the same age: high chance they knew each other. He died in 1943 and is mentioned in Tom Kitching’s diaries published by his son Brian (currently living in Perth, Scotland, and who I visited in July this year). I’d be so interested to read your grandfather’s diaries if they’re available? Best wishes, Gillie Turner