How (and when) to visit the Fitzwilliam museum…in the 1850s.

Many of you will have seen that the Fitzwilliam museum turned 200 earlier this month.

How would visitors born, like the museum, 200 years ago, have approached such a museum? Who were they and how were they expected to behave?

We might find clues in our Cam collection, which contains Cambridge imprints and books about Cambridge, both town and University, from the 16th century to the present day. There are now more than 10,000 items in this collection, to which new publications and purchases are still added.

There is, for instance, the Hand-book to the pictures in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (Cam.d.853.1), published by Macmillan in 1853. (This first publication was followed in 1855 by a Hand-book to the marbles, casts, and antiquities, in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.) There we can learn that the Museum was “Open for inspection from Ten till Four o’clock every day except Sundays, Christmas Day, Epiphany, Purification of the Virgin, Ash Wednesday, Good Friday, Easter Monday and Tuesday, Ascencion Day, Whitmonday, and Tuesday, and November Fifth”.

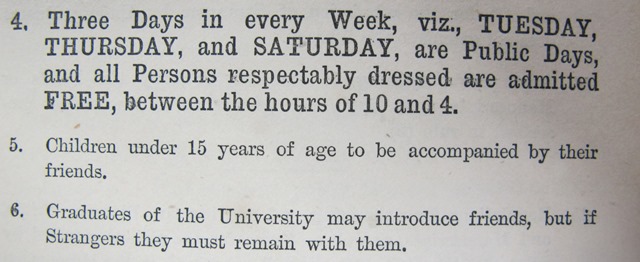

The Fitwilliam was, however, a “university Museum”: there were limited hours when the general public could visit. At the time of the publication of this first hand-book, the public was only admitted on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons. Every graduate of the University could “introduce strangers or friends”; but if stranger, the hand-book sternly warns: “It is required to remain with them during all the time they are in the building”.

A rapid increase of “public time” would soon follow. In 1857 the public hours were extended to all day on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, and from 1869 onwards, Mondays and Wednesdays from 1 p.m.

In 1863, a Visitor’s guide to the Fitzwilliam Museum (Cam.e.868.1) was published by William Metcalfe, of Trinity street. Its aim was to “give the Visitors to Cambridge, in a condensed form, as complete a list as possible of the Paintings, Sculptures, &c., with faithful remarks upon those that are especially worthy of their attention, and thus to save time in the short space allotted for their examination”. In its sturdy green cloth binding, and only 15 cm high, it was the perfect guidebook for the newly appearing tourists to slip into their pocket or handbag.

One intriguing rule commands that “Children under 15 years of age” had to be “accompanied by their friends”, (which may sound to some of you like a recipe for disaster.) As surprising as these rules can appear today, they were a move towards making the museum a place of learning and enjoyment for all.

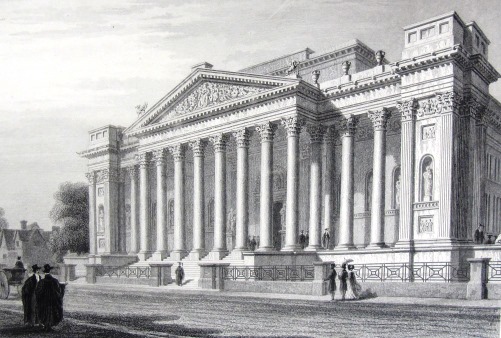

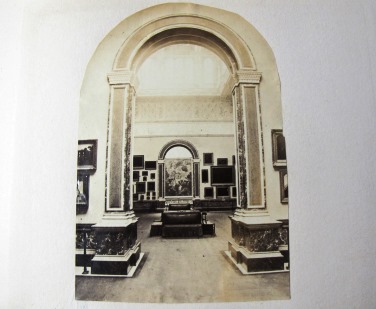

The picture galleries as they appeared to visitors in 1866, in Samuel Sandars’ copy of Memorials of Cambridge (Cam.b.860.5-7)

Lucilla Burn, in her very recent publication, The Fitzwilliam Museum, a history (also available in our Cam collection at Cam.b.2016.1), notes that before 1876, the Museum had no Director. It was managed by a committee, or Syndicate, consisting of ten senior members of the University, and chaired by the Vice-Chancellor. For these academics, “assuming responsibility for the effective management of a major public museum represented a move into an unfamiliar territory”. Their policies, however, do show that they were keenly aware, and contributing to, the discussions and changes that were shaping the development of museums in the second half of the nineteenth century.

The Museum was thus increasingly opened to the general public, rather than solely to the members of the University.

The visitors’ guide advised its readers to consult the hand-books published by Macmillan, should they wish for “a history of the various artists, and a classical description of the “sculptures, marbles, &c.” It also refers to the Memorials of Cambridge, a luxurious publication summarising the great monuments and institutions of the University town, and of which a 1866 edition, complete with etchings, engravings and contemporary photographs that used to belong to the bibliographer and collector Samuel Sandars is now kept in the Cam Collection (Cam.b.860.5-7).

Together, these three types of publication combine to give us a glimpse into the world of Museums, and of Cambridge, that you would maybe have known, had you been born 200 years ago…