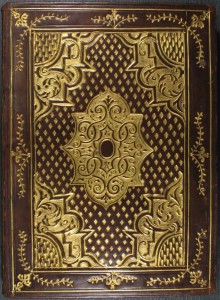

Samuel Sandars the collector

An example of Sandars’ fondness for beautiful bindings. An English gilt binding c.1600 on “Discorsi del molto r. padre d. Vitale Zuccolo sopra le cinquanta Conclusioni del sig. Torquato Tasso” (Bergamo: 1588) SSS.56.11

A few weeks ago, Cambridge University Library advertised this year’s competition for the 2014 Rose Book-Collecting Prize [entries due no later than Tuesday 14th January], which offers students the chance to win £500 by building their own book collections. It is advised that “the judges will make their decision based on the intelligence and originality of the collection, its coherence […], as well as the thought, creativity and persistence demonstrated by the collector and the condition of the books. The monetary value of the collections will not be a factor in determining the winning entry…”. These qualities are perfectly demonstrated in the collections of two nineteenth-century collectors; John Couch Adams and Samuel Sandars, which I recently had the chance to explore. Both collections were bequeathed to the University Library in the 1890s, and both were built by proud Cambridge alumni, but they both illustrate different aspects of the qualities enumerated above.

An Elizabethan embroidered binding on a copy of John Udall’s “Certaine sermons” (London: 1596), SSS.24.32

Samuel Sandars certainly demonstrated coherence and persistence in the building of his relatively well-known collection; and Adams’ collection, although of a lesser monetary value, would win a price for creativity, and, well, persistence too! In this post, I would like to explore Samuel Sandars’ donations in detail, for they were many, to the University Library. Sandars collected both printed books and manuscripts, with the former now in the care of the Library’s Rare Books department, at the classmark SSS. Its 1490 items include 109 incunabula (books printed before 1501). Sandars was born in 1837, the son of a Conservative MP. He went to school at Harrow, and came up in 1857 to study at Trinity College. In 1860 Sandars graduated and began a career in law, although he never practiced. Living in London, he became a constant visitor of the British Museum Reading Room and in February 1868, joined the Cambridge Antiquarian Society; in 1869 he published a book on the history and architecture of Great St Mary’s Church for the Society. The Donations Register of the Library records his first donation in 1869, a sheet of c. 1700 listed together with a volume of pamphlets relating to Cambridge.

A sixteenth-century French ‘Grolieresque’ binding on “Les dialogues des Troys Estatz de Lorraine” (Strasbourg: 1543) SSS.10.17

Exploring the collection shows that Sandars started to be interested in books and book collecting well before leaving Cambridge. SSS.49.4, Charles Hartshorne’s “Book rarities in the University of Cambridge: illustrated by original letters, and notes, biographical, literary and antiquarian” (London: 1829), bears the inscription “Saml Sandars, Trin Coll Cambridge 1858” and is full of notes and corrections by Sandars. It is also inscribed “For the Cambridge University Library”. It was often revisited by Sandars throughout his life and is a fascinating milestone in the development of this bibliophile. This would culminate at his death in 1894, with a bequest by which “all books [from Sandars’ library] printed on vellum or satin of any date whatsoever, also all other books relating to the arts of bibliography, palaeography, binding or typography excepting books bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam” would go to the University Library.

Following (last month) the sale of the most expensive printed book to a private collector who plans to loan it to libraries across the USA, it is interesting to remark upon Sandars’ strangely “public-but-secret” mind-set. Upon donating Bulwer’s Artificial Changeling, in 1879, Sandars wrote to Henry Bradshaw: “[this book is] only fitted for a public collection. I hope you will keep it under lock and key or it will soon vanish” (Letter from Sandars to Bradshaw, 16 October 1879, quoted in Cambridge University Library: A history – McKitterick, 1996, p. 695, n. 97).

The engraved frontispiece from “Universal harmony or, The gentleman and ladie’s social companion” (London: 1745) SSS.59.15

Sandars’ last letter to Francis Jenkinson, University Librarian, on 13 June 1894, ends with a final illustration of his desire to help the Library: “13 June: I am glad you have the Portuguese early printed book from Quaritch’s last catalogue…I shall be very pleased to send you a cheque for the amount and make it my gift which will free a small sum for another volume”. Samuel Sandars died two days later. Samuel Sandars had a fondness for beautiful bindings and was attracted to the rare, the beautiful, and the exceptional. But mostly so far as it could benefit Cambridge and particularly Cambridge University Library. Sandars was one of the first to turn his attention to the University Library as an institution to such an extent that he collected for it, rather than for himself; and started to offer books to the University Library well before his death. Now, dear reader and potential collector, this is not a hint that Sandars was the only model to follow (although, of course, you could start collecting incunabula to offer to your favourite Library if you felt so inclined). Indeed, another collection (that of John Couch Adams), bequeathed only two years before Sandars’, gives a very different example of what nineteenth-century collectors’ libraries could be. A post on this collection will follow.

By Dr Sophie Defrance (formerly of the Rare Books Department)

Pingback: How (and when) to visit the Fitzwilliam museum…in the 1850s. | Cambridge University Library Special Collections