Martin Bucer and the Reformation in Cambridge

Bucer’s portrait in Boissard’s Icones quinquaginta virorum illustrium (Frankfurt, 1597-9), Syn.6.59.8

Between 17th and 19th March, a number of Cambridge librarians – along with a host of academics – spent a happy time in the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, for a conference on the life and work of the library’s founder, Matthew Parker. Nearly twenty papers were presented over three days, covering various aspects of Parker’s life: book collector, Archbishop of Canterbury, Master of Corpus Christi College and Biblical editor, not to mention his reception after the sixteenth century and the digital approach to the books he gathered together. Parker – at least among scholars of library history – is remembered primarily for his spectacular bequest of well over 1000 printed books and manuscripts to his college, including many Anglo-Saxon volumes, and an illuminated Gospel book believed to have been brought to this country in 597 by Augustine, who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. Less well-known is Parker’s gift to the University Library, in 1574, of twenty-five printed books and seventy-five manuscripts. But it was a paper by Professor Brian Cummings (University of York), on Parker, Bucer, and the Book of Common Prayer, which got me thinking about a set of books in the University Library with resonant connections to the English Reformation in Cambridge.

Martin Bucer (1491‒1551) was born near Alsace but spent much of his life in Strasbourg. Having joined the Dominican order as a teenager he soon became a full friar in the order and in 1510 was consecrated as a deacon. By 1515 he had moved to Heidelberg to study, was ordained priest in Mainz in 1516 and in 1517 returned to Heidelberg to enrol at the University there. His interest in books took hold quickly and in 1518 (aged 26) he made a list of the books then in his possession, which numbered nearly sixty titles, including Erasmus and Thomas Aquinas (another Dominican). Printed books and pamphlets, particularly those by Luther and Melancthon, circulated widely and allowed Reformation teaching to spread quickly. Also in 1518 Bucer met Luther, who had travelled to Heidelberg, and his connection with this great reformer caused him to cut his ties with the Dominicans, who released him in 1521.

During the 1520s he became more involved in the Reformation – which sought to limit the power of the Church and re-focus on the Bible as a source of authority – and in 1523 moved to Strasbourg, a centre of reformed learning. He debated issues like the eucharist, and whether or not the body and blood of Christ were truly present in the bread and wine, or just symbolic. To cut a long story short, after clashing with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1548 Bucer was forced to flee the Continent, and in April 1549 he arrived in London (with Paul Fagius and others), at the invitation of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. A few days after their arrival Cranmer presented them to the young King Edward VI. Bucer was appointed Regius Professor of Divinity at Cambridge and hoped to disseminate Protestant theology throughout England, but was thwarted by those in authority, along with smaller controversies around the eucharist and the wearing of vestments by the clergy.

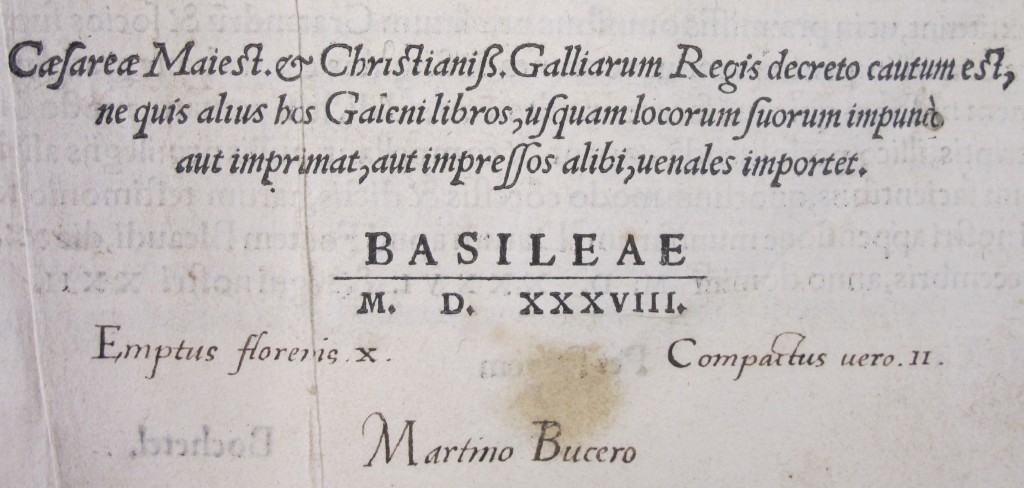

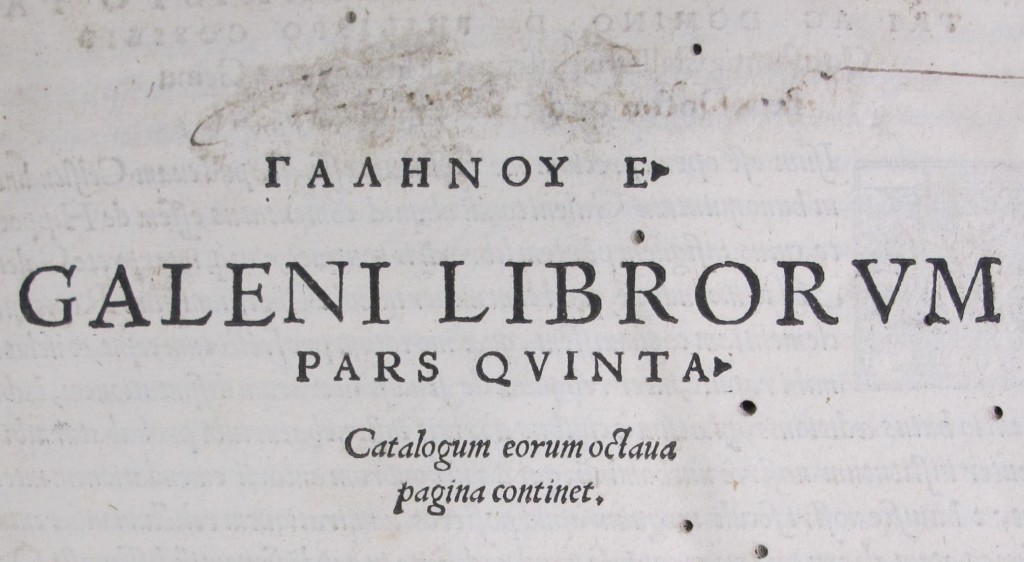

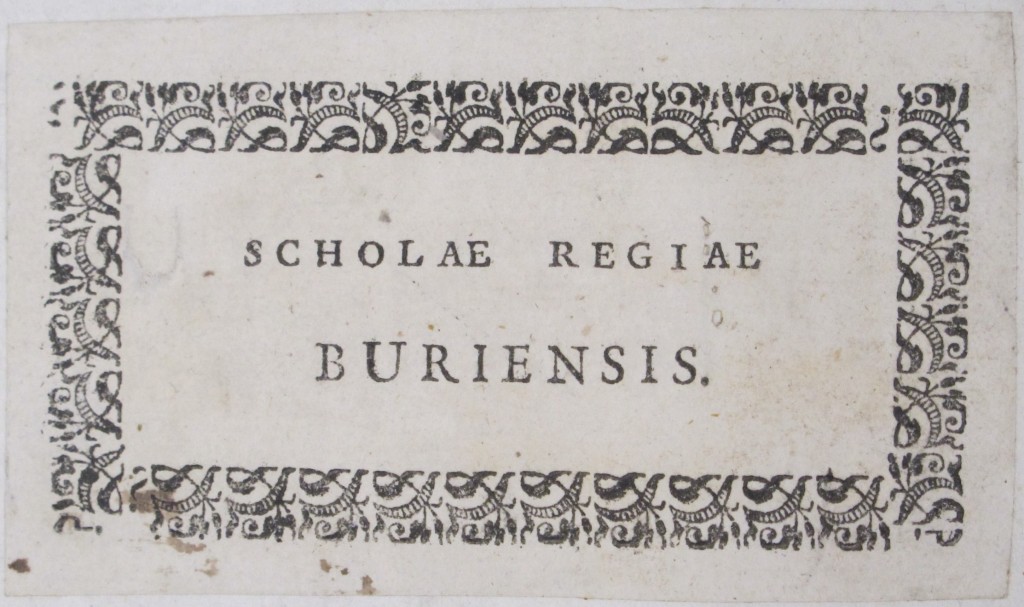

The English (or pehaps Fen) climate did not suit Bucer, and he suffered from a number of ailments during his time here, including rheumatism and coughs. He died on 28 February 1551 and was buried with great ceremony in Great St Mary’s church. After his death his large library was apparently divided between the king (Edward VI), Frances Gray (Duchess of Suffolk) and Archbishop Cranmer, although some of Bucer’s personal papers made their way into the hands of one of his executors, Matthew Parker, and are now at Corpus Christi College. Cranmer is said to have paid Bucer’s wife Wibrandis Rosenblatt £40 for his group of books from the library, a sizeable sum, but few of Bucer’s printed books – from Cranmer or other sources – have been traced today. One work from Bucer’s library found its way (in 1970) into the University Library: a 1538 edition in five volumes of the works of Galen, printed in Basel (where Bucer’s wife spent much of her life). Bound in contemporary blindstamped pigskin the set was evidently among the books which made their way into Cranmer’s hands in 1551, for his name – in the form Thomas Cantuarien[sis] – has been (poorly) erased from the title page of volume five and probably cut out of the other four (its usual form can be seen in this book from St John’s College). Bucer’s name appears on the title page of volume one and is accompanied by the price: 10 florins. These inscriptions are not in Bucer’s own hand, but in that of his secretary, Conrad Hubert. After Cranmer’s death the books were acquired by Thomas Oliver (d. 1624), who entered Christ’s College in 1569 and was, by 1597 and probably earlier, practising medicine at Bury St Edmund’s. He wrote a book on astronomy – A New Handling of the Planisphere (1601) – alongside a number of short works on subjects including Aristotle and medicine. In 1595 he gave this set to the school at Bury (founded in 1550 by King Edward VI), where it remained until 1970 when the school library was deposited in the University Library.

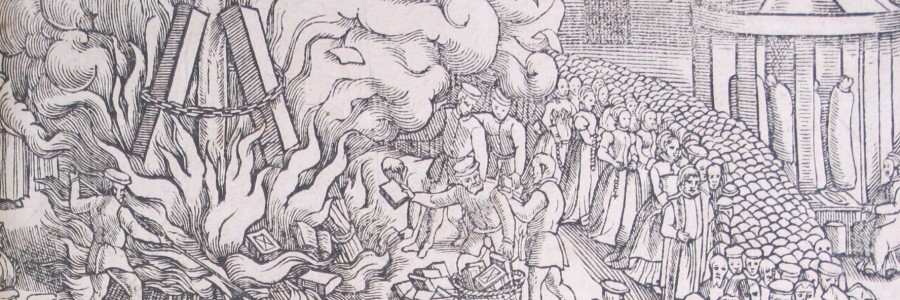

Bucer’s death was not the end of his involvement in the turbulent life of sixteenth-century Cambridge: with the coming of Mary I to the throne in 1553, the Protestant Reformation in England was overturned, and Catholicism restored. On 16 February 1557 the bodies of Bucer and Fagius were exhumed from Great St Mary’s, put into new coffins and burned in the market square, on a pyre fuelled with books (presumably copies of their own works), as can be seen in the image at the head of this post (taken from Foxe’s Actes and monumentes of 1563). Both men were officially restored under Elizabeth I and the presence of Bucer’s books in Cambridge seems appropriate, given his connections with the University. The Library holds a number of other books formerly in the possession of important figures of the Reformation: a work on Genesis by the German reformer Valentin Krautwald (Strasbourg, 1530) from the library of Hugh Latimer can be found in our Sandars collection, and a volume of poetry by Gregory of Nazianzus (Venice, 1504) with a gift inscription by Erasmus (who also spent time at Cambridge) is in the Bible Society Library.

Further reading

On Bucer in Cambridge and the publication of his De regno Christi, see B. Pohl & L. Tether, ‘Remigius Guidon, Cambridge’s Old Paper Mill and the beginnings of Cambridge University Press, c.1550–1559’, pp. 177-228 in Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society XV/2 (2013)

For Bucer’s 1518 book inventory, see J. Rott, Correspondance de Martin Bucer (Leiden, 1979), vol. 1, pp. 42-48

On Cranmer’s books, see D. Selwyn, The library of Thomas Cranmer (Oxford, 1996), and for Bucer’s copy of Galen, pp. 145-6

On the King Edward VI School at Bury, see A. T. Bartholomew and C. Gordon, ‘On the Library at King Edward VI. School, Bury St Edmunds‘, pp. 1-27 in The Library (3rd series, 1) 1910

Pingback: In the footsteps of Erasmus | European languages across borders

Pingback: Reformation lives | Cambridge University Library Special Collections