Reformation lives

One of the great joys of working with special collections in an historic library like the UL is the discovery (or re-discovery, with each new generation of library staff) of objects with direct links back into the past. We call this provenance: tracing the history of single volumes or whole collections through the lives of the people who have owned them. In retrieving two such volumes for a researcher last week – involved with the very interesting AHRC-funded ‘Remembering the Reformation’ project based at the Universities of Cambridge and York – I was reminded of the power such links – to great individuals long dead – can exercise upon people today: a commentary on the book of Genesis (Strasbourg, 1530) owned by the Oxford Martyr Hugh Latimer, and a volume of poetry by Gregory Nazianzus (Venice, 1504) owned by the great Renaissance humanist Desiderius Erasmus.

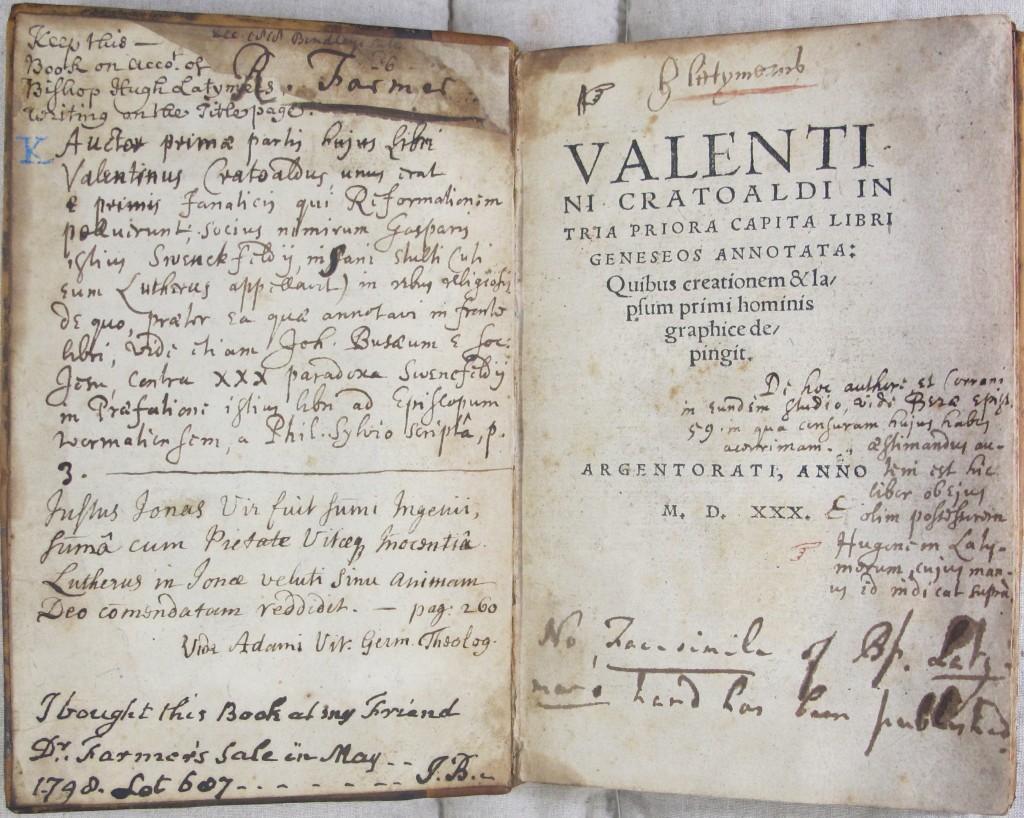

Latimer’s inscription to the head of the title page, with Richard Farmer’s annotations below (SSS.53.2)

First, Latimer. The book in question, ‘Annotata in tria priora capita Geneseos‘, is by the German reformer Valentin Krautwald and was printed in Strasbourg in 1530. The edition is not especially rare (the UL has two other copies – one from Peterborough Cathedral Library) and there are a further three copies in the UK (British Library, Bodleian and the National Library of Scotland). But at the head of the title page is the inscription ‘H. Latymerus’ in a sixteenth-century hand. Latimer was born c. 1487, studied at Cambridge (BA 1510/11, MA 1514) and became a fellow of Clare College here in Cambridge in 1510. In the 1520s he was part of the circle of protestant reformers who met at the White Horse Tavern in Cambridge (in existence until 1870, when it was demolished to make way for an extension to King’s College’s screen) to discuss Luther’s radical new ideas. The site is now marked by a plaque.

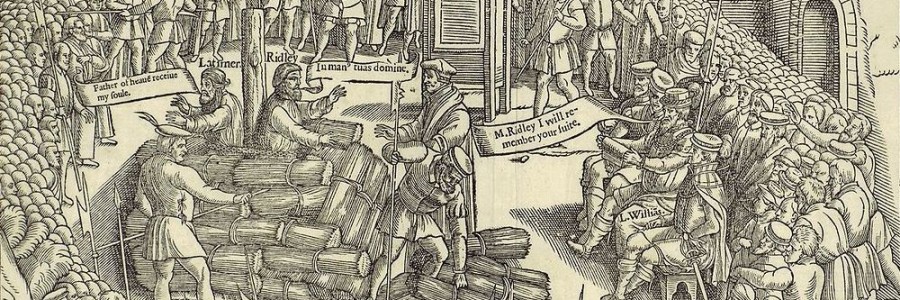

He rose to become Bishop of Worcester in 1535 but was deprived four years later when he opposed Henry VIII’s six articles. Though he returned to favour as a court preacher under Edward VI his protestant leanings led to his imprisonment and trial under Mary I; in 1555 he was burned at the stake, alongside Nicholas Ridley, outside Balliol College in Oxford (see the image at the head of this post, from Foxe’s so-called Book of Martyrs). With the similarly sticky end met by Thomas Cranmer in the following year were born the so-called Oxford Martyrs.

It is not known to whom Latimer’s books passed after his death, but this volume was evidently treasured. The long note in the middle of the title page, in a late sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century hand, mentions Latimer’s ownership, as does a long seventeenth-century note to the upper half of the front pastedown. Its first recorded owner post-Latimer is the great Richard Farmer, whose name is inscribed on the front pastedown, and who added both a manicule next to Latimer’s name on the title page and a note recording that ‘No facsimile of Bp. Latimer’s hand has been published’. Farmer – Shakespearean scholar, Master of Emmanuel College (1775-1797) and University Librarian (1778-1797) – had a vast personal library containing many so-called ‘black-letter’ (early English) works and evidently appreciated the illustrious former owners of many of his books. A fine portrait of him hangs on the fourth floor landing in the UL, his rather stern face in contradiction to the picture painted in his DNB entry, which notes that ‘there were three things … he loved above all others, namely, old port, old clothes, and old books; and three things which nobody could persuade him to do, namely, to rise in the morning, to go to bed at night, and to settle an account’. At the sale of his collection in May and June 1798 this volume was lot 687, where it was sold for 1s 6d (along with lot 688) to James Bindley (1737-1818), a fellow of Peterhouse, who inscribed the front pastedown ‘I bought this book at my friend Dr Farmer’s sale’. It was presumably sold again after Bindley’s death though I have not been able to find it in any of the sale catalogues of his library (at least four sales between 1818 and 1820). It later passed to the voracious bibliophile Richard Heber, turning up as lot 1360 in the second of his sales (June 1834), the catalogue (put together by the great T. F. Dibdin) noting that it is ‘With Hugh Latymer’s autograph’, an early example of the inclusion of provenance information in sale catalogues. Finally it passed at an unknown date to Samuel Sandars – graduate of Trinity College and friend of University Librarian Henry Bradshaw – whose impressive collection of early English books (many in fine bindings and from significant collections) was bequeathed to the UL in 1894, along with £2000 for the establishment of an annual series of lectures on bibliography, which are still given today.

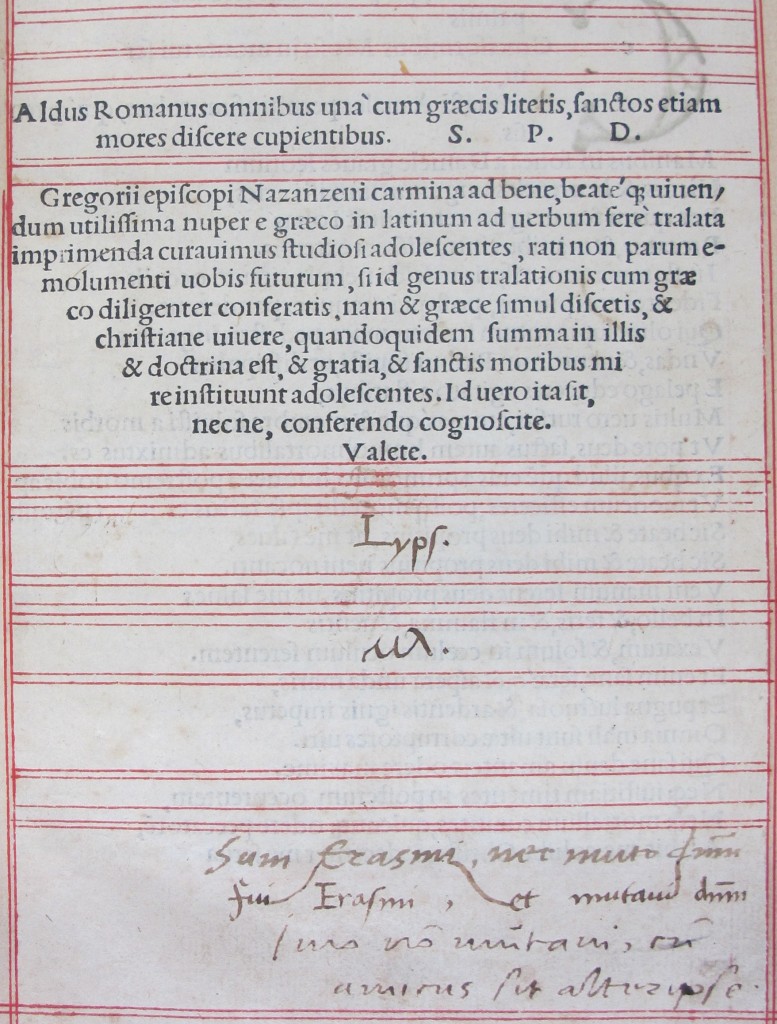

Secondly the Erasmus: the Carmina (poems), in Greek and Latin, of Saint Gregory of Nazianzus, printed by the great Venetian printer Aldus Manutius in 1504. Erasmus (1466-1536) began his life in Rotterdam, but travelled Europe, settling briefly in Cambridge as Lady Margaret’s Professor of Divinity, staying at Queens’ College between 1510 and 1515. He seems not to have taken to the English weather, or to the local beer, and by 1517 he was in Leuven founding a school for the study of Hebrew, Latin and Greek. In 1516 – five centuries ago – he published the first Greek edition of the New Testament, and it is this anniversary which is the subject of an exhibition (and major cataloguing project) at Queens’ this year. Like Latimer’s book, it is not rare (Aldus’ books are to be found in libraries across the world) but the series of inscriptions on the title page bring us right back to the sixteenth century, into the heart of a friendship between two scholars, for they record Erasmus lending the book to his friend Martin Lipsius. At the foot of the title page, in Latin but translated here, we find the following: [Erasmus] I belong to Erasmus and I do not change my master – [Lipsius] I did belong to Erasmus and I have changed my master – [Erasmus] I have not changed because a friend is a second self. The book featured in the UL’s 2011 exhibition commemorating the 400th anniversary of the publication of the King James Bible.

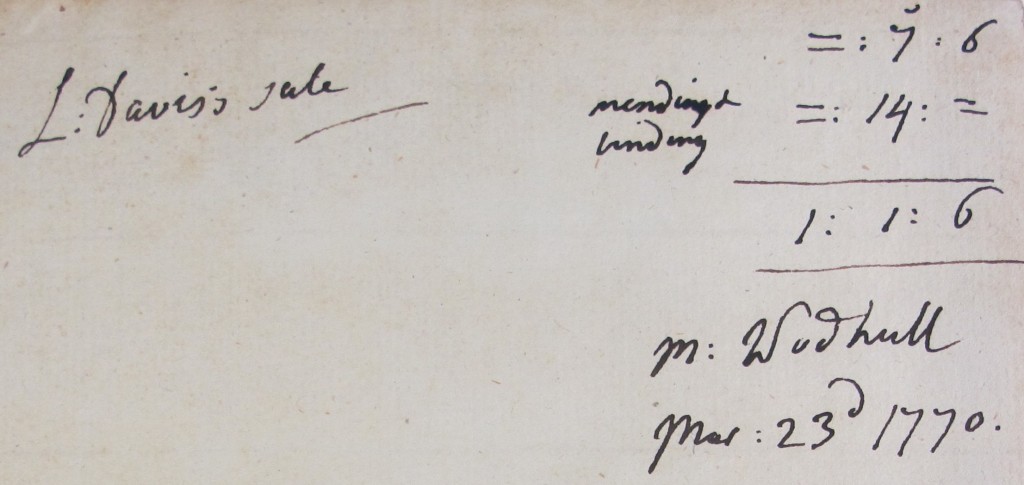

It is not known who owned the book between Lipsius’ death in 1555 and its next owner in the eighteenth century. But in March 1770 it appeared in a catalogue produced by the London bookseller Lockyer Davis, where it was item 1831, with no mention of the connection to Erasmus. Entitled ‘A catalogue of a very large collection of valuable and curious books…’ it contained books from a number of libraries, but especially from those of three individuals: Rev. Mr Alleyne (Rector of Stantone, Leicestershire), Dr John Barham (of Lewes, Sussex) and Mr Richard Webb (Surgeon to St Bartholomew’s Hospital). Given the religious connection it is tempting to think it came from the Rector, but we can never be certain.

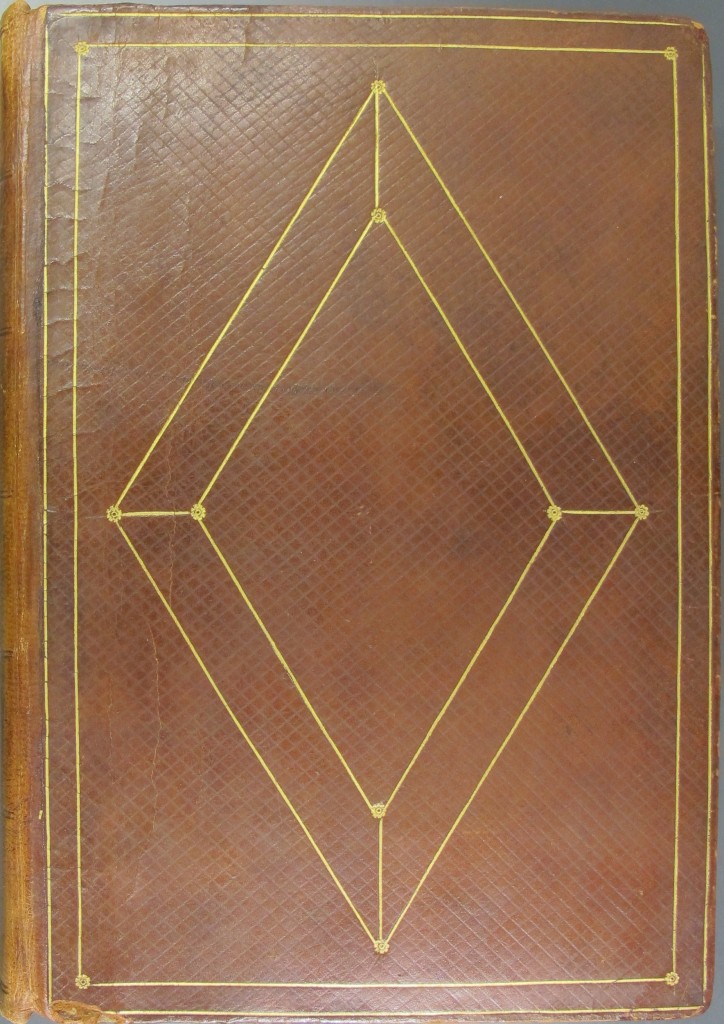

It had the good fortune to be purchased by the poet and book collector Michael Wodhull (1740-1816), known for leaving detailed notes inside his books which are now very useful for interested librarians. He records that the book cost him 7s 6d from Davis’ catalogue, that he paid 14s for ‘mending & binding’ and that the book returned to him on 23 March 1770. Bequeathed by Wodhull to his sister-in-law Mary Ingram in 1816, it passed in 1824 to Samuel Amy Severne of Thenford House, Banbury, and was probably lot 1183 in the sale of Wodhull’s books (by then owned by J. E. Severne) at Sotheby’s in January 1886. Its binding (possibly by Roger Payne) was considered worth a mention in the sale catalogue, but again, the connection to Erasmus failed to make it into print. Finally the book was presented to the library of the British & Foreign Bible Society, founded in 1804 and housed in a vast building on Queen Victoria Street in the City of London until the 1980s, when the Society gave its library on deposit to Cambridge, where it remains an immensely valuable resource for those studying the history of Bible translation.

A recent post on this blog talked about another book with significant connections to Reformation figures, but there are thousands of other books with illustrious lineages to be found in the UL’s collections whose stories are waiting to be told.