John Fisher (ca 1469-1535), martyr (and archivist)

John Fisher’s principled opposition to Henry VIII’s divorce from Katherine of Aragon resulted in his conviction for treason and execution in 1535. Everyone remembers the dramatic ending of the man who was also, variously, Bishop of Rochester, Cardinal, first Lady Margaret Professor of Theology, and Chancellor of the University. Now, evidence of his youthful enthusiasm for archive administration is revealed in the mainly fifteenth-century ‘Inventories of books, records and other movable property of the University’ (classmark: UA Collect.Admin.4), digitised as part of the Library’s 600th anniversary collection in the Cambridge Digital Library.

Fisher graduated BA in 1488 aged about twenty and proceeded MA in 1491. Having become a fellow of Michaelhouse he was ordained priest that same year in York. He advanced rapidly in the University serving as Senior Proctor in the academic year 1494-5.

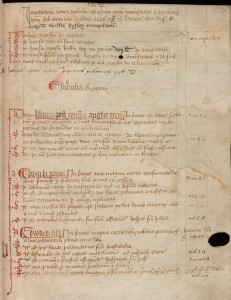

Best known nowadays as upholders of discipline, the Proctors were originally the University’s chief executive officers and responsible for its finances. Several detailed inventories, bound into a Register in 1473, helped them keep track of its moveable property in the form of money, other valuables, and muniments, that is, charters of privilege and deeds of title, stored in chests in the chapel, in the north range of the Schools buildings.

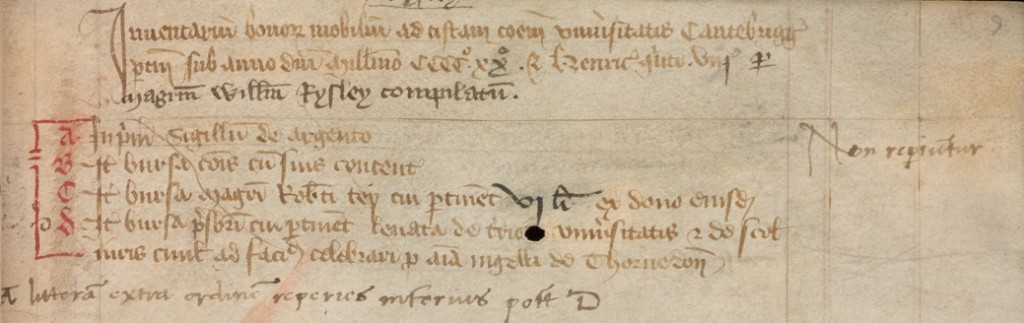

A certain Master William Rysley (who was probably a Proctor) wrote an inventory of the University Chest in 1420, beginning with the University seal of silver and cash in three purses and going on to the muniments. In doing so he left us the first catalogue of the University Archives. Roughly classified and kept in smaller bags or boxes marked A-N, each document bore an individual letter a, b, c etc.

Rysley’s became the standard list by which the muniments were checked for the next 80 years; corrected and kept up to date by various writers. The last and most thorough revision was by John Fisher as Proctor who, having looked carefully through the Chest, wrote ‘non reperiuntur’ (‘they are not to be found’) in the margin against several sections.

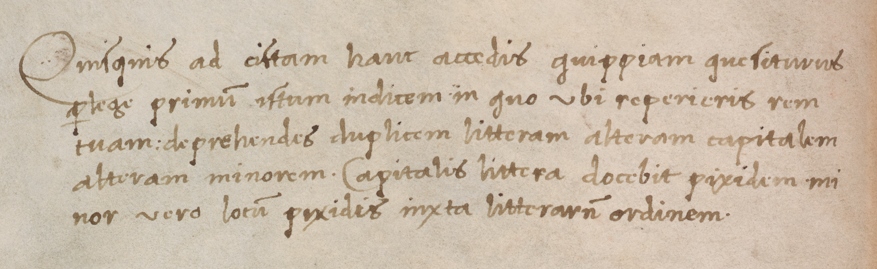

As well as adding new records, he prefaced the inventory with a short instruction on how to find individual documents:

Quisquis ad cistam hanc accedis quippiam quesiturus perlege primum istum indicem in quo ubi reperieris rem tuam; deprehendes duplicem litteram alteram capitalem alteram minorem. Capitalis littera docebit pixidem, minor vero locum pixidis iuxta litterarum ordinem (‘Whoever comes to this chest in search of something, first read through this index to find your topic; ascertain both letters, large and small. The large letter will indicate the box, the small the place in the correct box according to letter order’).

Whatever Fisher’s care in emending and explaining the archival ‘finding aid’ (in modern parlance), it is doubtful that much use was made of the revised catalogue, for after this all additional entries cease. In the new century were to come administrative and other changes which would render obsolete many of the medieval muniments of the University.

Pingback: Picturesque and the prosaic launch to Cambridge University Archives collection in the Digital Library – Cambridge University Library Special Collections