The Transmission of Knowledge in the Early Middle Ages

A guest post from Johanna Jebe, Maximilian Nix, Luise Nöllemeyer, Bastiaan Waagmeester and Elena Ziegler, PhD students from the University of Tübingen.

Between June 30th and July 1st 2017, sixteen PhD students and post-doctoral scholars from Berlin, Tübingen and Cambridge met at Cambridge University Library for an in-depth look at some of the Library’s medieval treasures. The workshop was organized by Professors Rosamond McKitterick, Stefan Esders and Steffen Patzold with the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (German Academic Exchange Service), in order to connect early-career scholars from these three universities and give them the chance to study manuscripts from Cambridge. The group met last year at the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Berlin, and now deepened their knowledge of manuscript studies, with a focus on intellectual exchanges between Britain and Frankish regions, the construction of a Latin literary culture during the early middle ages, the characteristics of certain scriptoria, and the history of the manuscript collections in Cambridge.

Dr James Freeman, the Library’s Medieval Manuscripts Specialist, presented 22 early medieval manuscripts, which varied from fragments to richly illuminated manuscripts. The participants were able to examine the manuscripts intensively. Although modern technology makes it possible to see many manuscripts online, from all over the world, the careful study of the originals gave many insights a digital reproduction simply cannot provide. Professor McKitterick shared her expertise in palaeography and codicology, and emphasized the historical importance of the manuscripts.

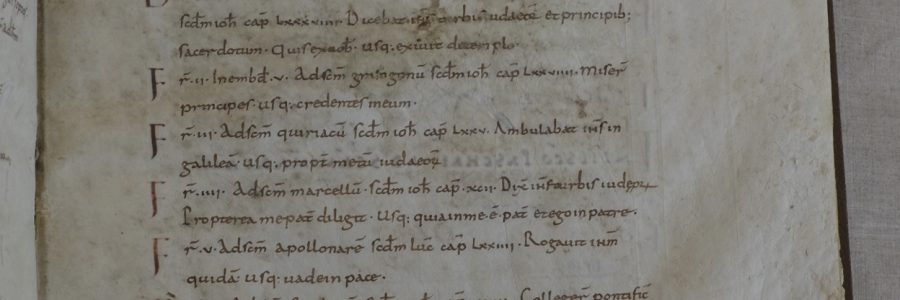

Pairing of biblical readings with the performance of the mass at St Peter’s and at the Lateran – MS Add. 563, f. 6r

One prominent theme arising from the studied manuscripts was the transfer of knowledge on the European continent, and its mediation by books and people. For example, MS Add. 563 is part of a mid-9th-century gospel book that was used at the Carolingian court. Only seventeen leaves survive, bearing texts on the readings of mass and for specific saints’ feast days, as well as the liturgy for festal and ferial days, and material used for the dedication of churches and the ordination of clergy. The mass readings found at the beginning of the manuscript point towards the Roman tradition of stational liturgy: the text pairs certain biblical passages with locations in the city where they should be read, because in Rome the mass was not only performed in the Lateran but in the various churches throughout the city on a rotating schedule. Yet the script used and the episcopal consecration found at the end of the small codex strongly suggest a Frankish origin, presumably in western France. MS Add. 563 is, therefore, a clear example of the transmission of Roman knowledge being incorporated at the Frankish court, where the city of Rome was seen as a liturgical model.

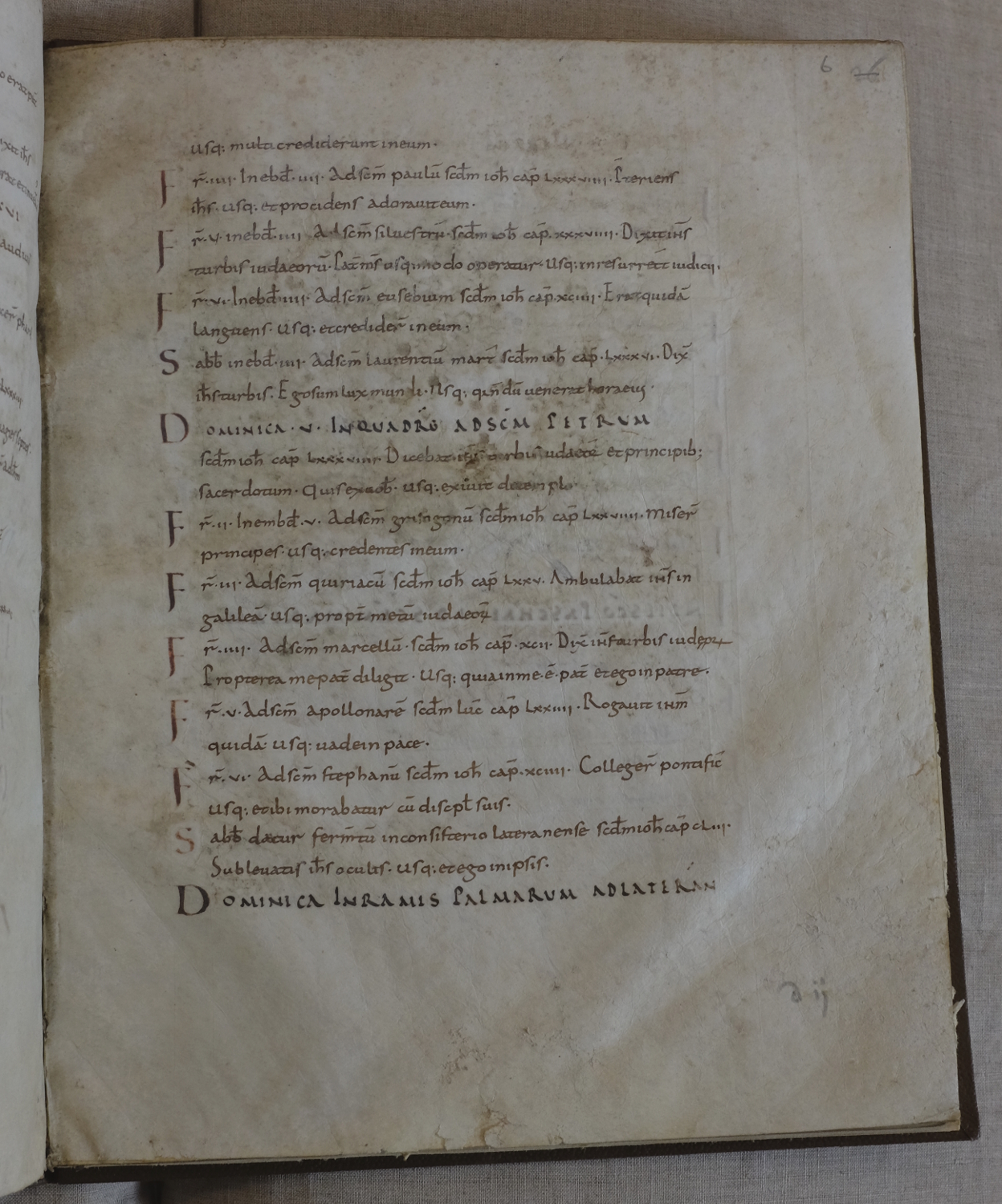

Glosses in Caroline minuscule, clarifying insular abbreviations for the words alit(er), q(uam) and q(uod) – MS Kk.5.16, f. 2r

In addition to the intellectual exchanges observed in the contents of manuscripts, the workshop took a special interest in recognizing and tracing particularities of script and page-setting between different scriptoria. The University Library’s collections offered an excellent basis for comparison: chronologically between the 8th and 9th century; between several early medieval writing centres; and across a wide and diverse range of scribal output, including classical and patristic texts, liturgical and biblical books, and Carolingian treatises. This focus on palaeography also opened the question of how books circulated and were distributed. MS Kk.5.16, the earliest copy of Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica, datable to the late 730s, is written in an early insular minuscule script, perhaps at Bede’s own monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow. It shows signs of later repeated and studious reading: the text is accompanied by careful glosses in a different style of handwriting, Carolingian minuscule. These notes explain unfamiliar insular abbreviations or comment on the text, and show how the book was studied meticulously by later Frankish readers, presumably at the court of Charlemagne. The manuscript is therefore not only a testament to the intellectual involvement and exchange of books between the British Isles and the Continent, but also formed the archetype for the transmission of Bede’s work through the Frankish world.

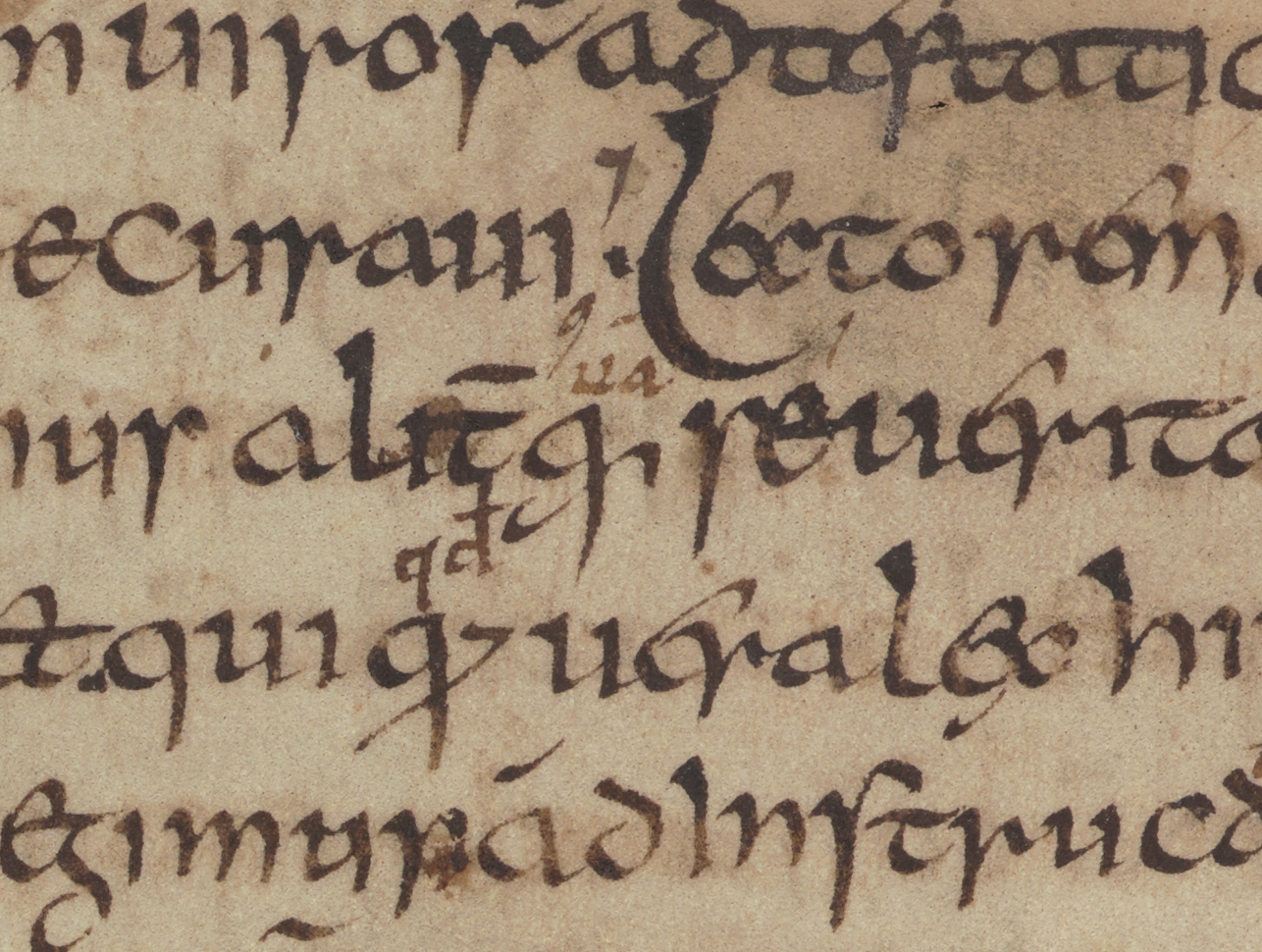

Fragment of a Martinellus, bound with a manuscript containing texts by Henry of Huntingdon and Bede – MS Gg.2.1, f. i recto

Tours is another scriptorium that appears repeatedly in surviving manuscripts as a distributive centre in networks of knowledge. MS Gg.2.21 contains a single leaf fragment from a hagiographical collection known as a ‘Martinellus’ that was made in the second quarter of the 9th century. While Tours is well-known for the ‘mass production’ of the bibles, scribes there were also active in copying these compilations that commemorated the life and miracles of the famous bishop, Martin of Tours (b. 316/336, d. 397). More than two-thirds of the 20 surviving ‘Martinelli’ are from Tours. Whereas most Carolingian schools copied primarily for their own libraries, Tours scribes copied books systematically for export and on commission. Even this single leaf illustrates the emphasis on quality typical of Tours manuscripts, with the text structured through a clear hierarchy of scripts or by systematic use of punctuation.

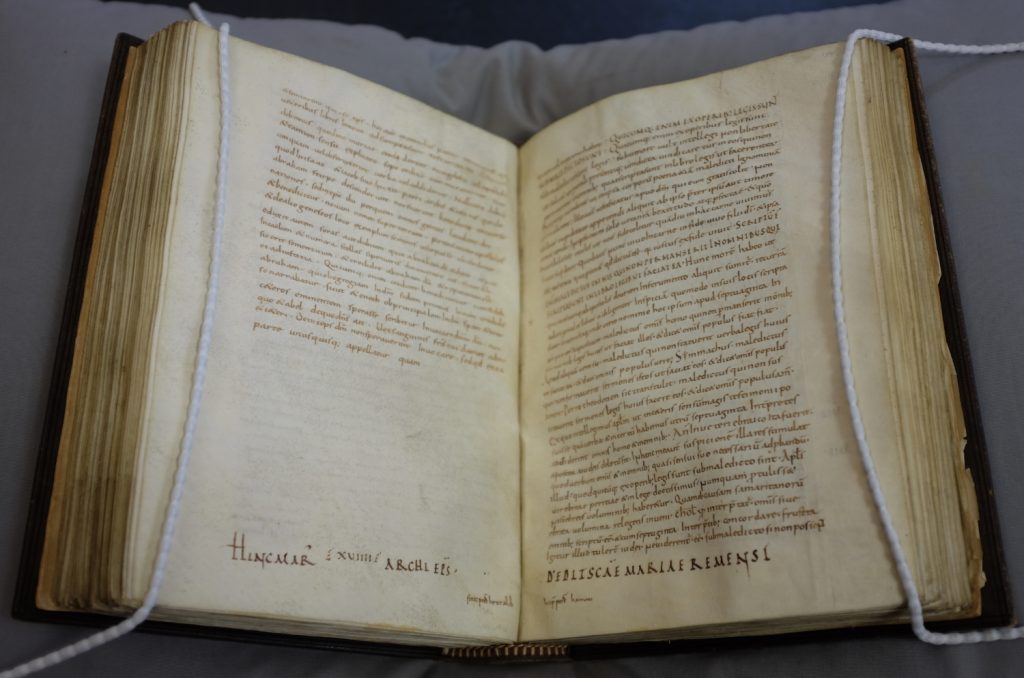

The end of one scribal stint and the beginning of another at a division between two quires – Pembroke College, MS 308, ff. 153v-154r

Other manuscripts from Tours gave insights into the processes of manuscript production: codicological examination of the quires of Pembroke College MS 17 (first half or mid-9th century) revealed that the manuscript was originally bound in two volumes and that its scribe combined the text of Jerome’s commentary on Isaiah presumably from two different models. Pembroke College MS 308, made between 845 and 882, revealed a systematic division of work and responsibilities at the scriptorium at Rheims. The manuscript was copied by a team of scribes: each copyist was given a portion of the exemplar, and their names were noted at the beginning and end of each corresponding portion of the copy (as seen in the accompanying illustration, at the bottom of the leaves near the gutter). Inscriptions recording the donation of the manuscript to the cathedral by Archbishop Hincmar were written in rustic capitals across the end of one quire and the beginning of the next, bridging the gaps between the physical units of the book and emphasising its cohesion.

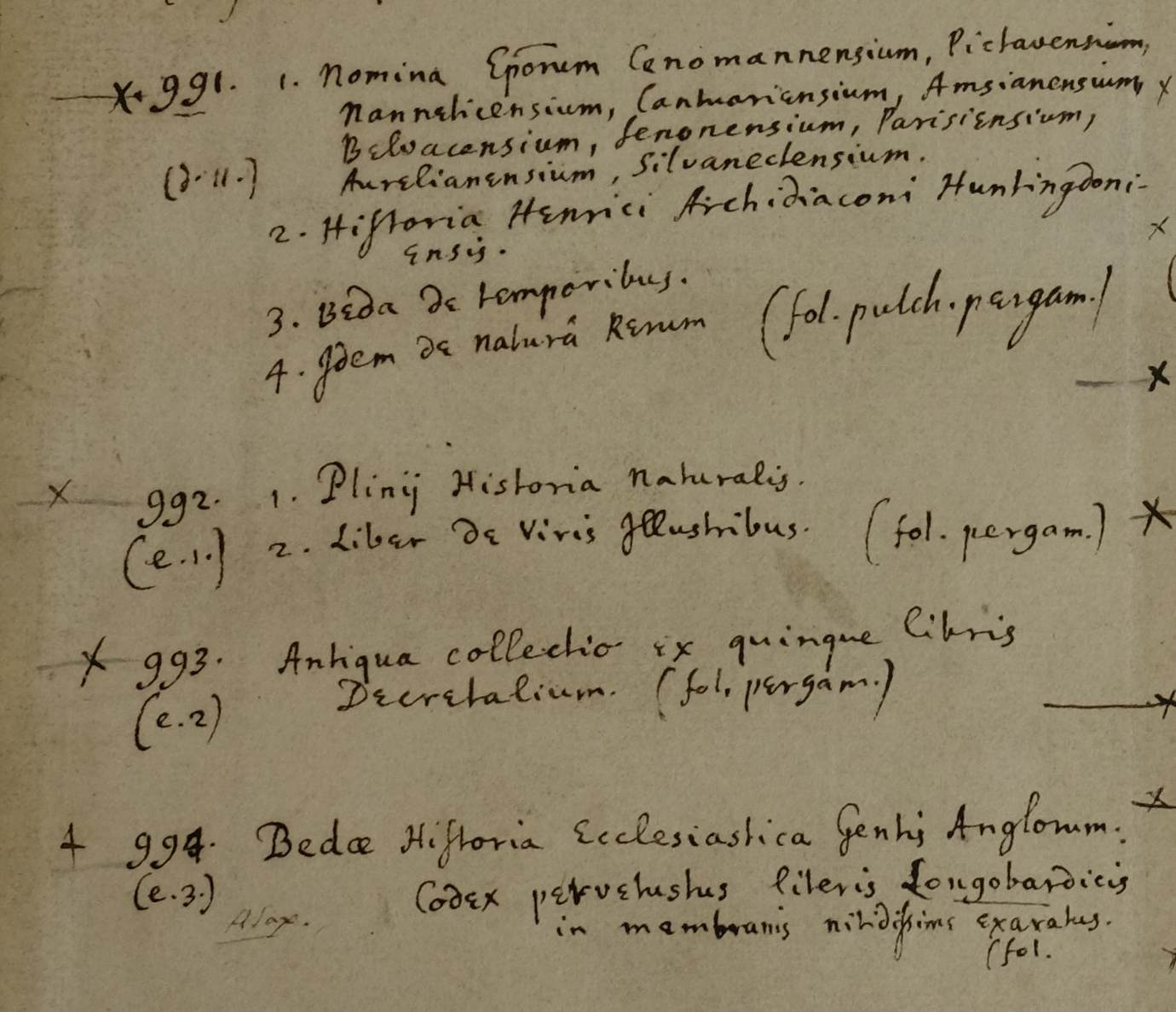

Supplementary list of Moore’s books made by Thomas Tanner, listing both Gg.2.21 (no. 991) and Kk.5.16 (no. 994), the latter mistakenly identified as written in Lombard script.

A third theme that emerged from the discussions was the variety of routes by which these manuscripts came to the University Library. While wills and inventories record the growth of the Library’s collections through successive benefactions dating back as far as 1416, the largest single benefaction was that which brought both the Martinellus and Bede manuscripts mentioned above: the gift in 1715 by George I of the library of John Moore, bishop of Ely, who had died the year before. Both manuscripts were among acquisitions made by Moore later in his life; neither is recorded in the inventory of Moore’s library published by Edward Bernard in 1697-98, but are to be found in Thomas Tanner’s handwritten inventory in MS Oo.7.50(2). Post-medieval collectors too played an important role in the preservation and transmission of medieval knowledge.

Complementary to these studies at the University Library was a tour through Wren Library at Trinity College. Among the medieval treasures seen was the richly illustrated ‘Canterbury Psalter’ (MS R.17.1, made between 1145 and 1170), and a 10th-century copy of Hrabanus Maurus’s De laudibus sanctae crucis (MS B.16.3) comparable to another from the 12th century at the University Library (MS Add. 4078).

Many thanks go to Dr James Freeman and Dr Suzanne Paul of the Manuscript Room of Cambridge University Library, who made possible this opportunity to have a look at the collections, as well as to Prof Rosamond McKitterick for organizing the workshop and sharing her unique knowledge of these manuscripts.

Dear James,

Thank you very much for this very insightful blog post. I am an M.A. student and currently in search of a topic for my masters thesis. Your article made me think a lot and gave me some amazing ideas.

Thank you very much!

Pingback: Englishing the Papacy: The Liber Pontificalis and MS Kk.4.6 – Cambridge University Library Special Collections