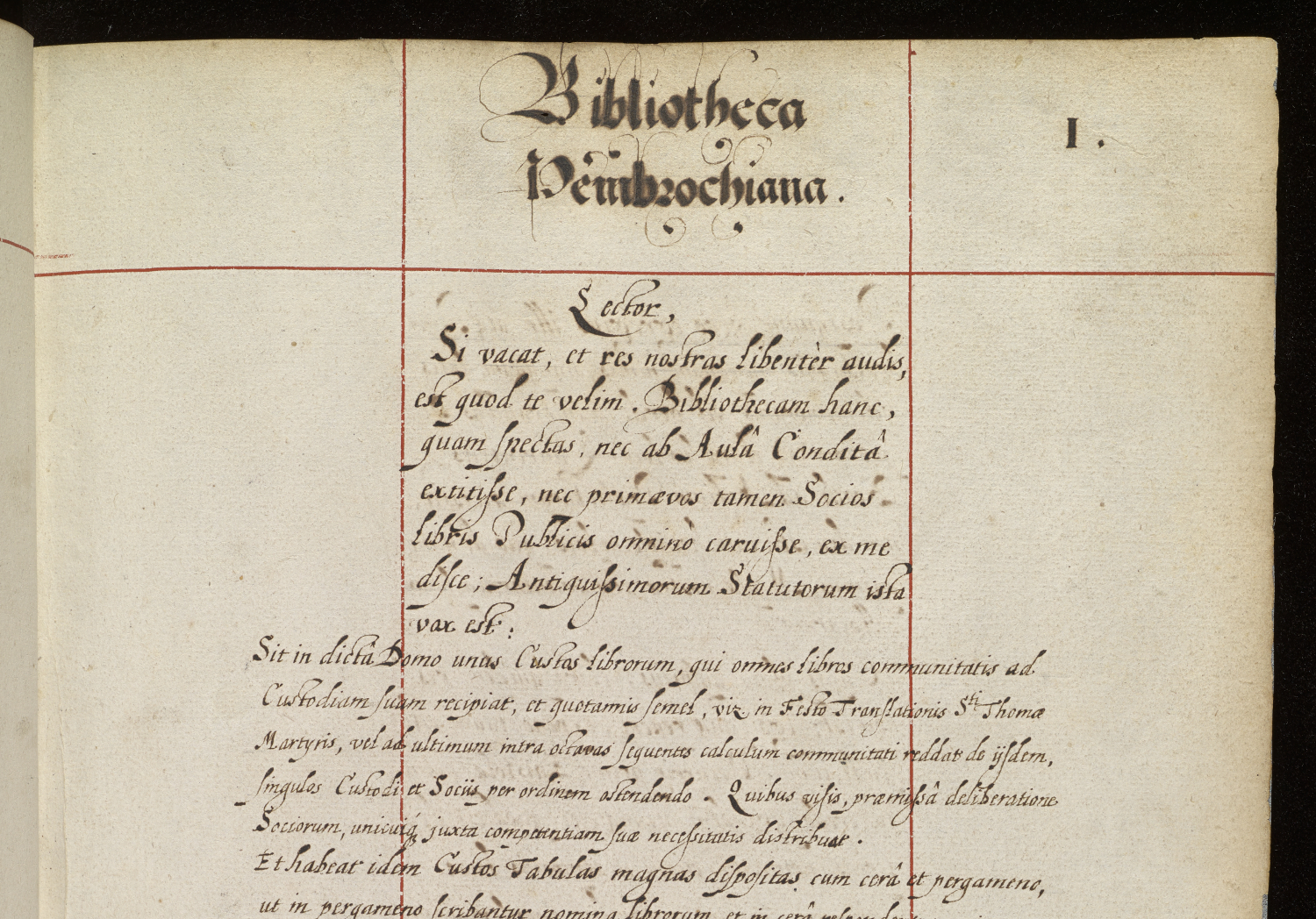

Pembroke College’s Benefactors’ Book

A guest post from Jonathan Nathan, who is studying for his PhD in History. He is investigating the circulation of underground atheist literature through pre-modern Europe.

Nearly every seventeenth-century college in Oxford and Cambridge had a ‘library benefactors’ book’, a manuscript volume that sumptuously recorded gifts to the college’s library. All of these books give us valuable information about the learned communities that had them made. Gifts of books in particular were vital to the intellectual life of every college, since they tended not to buy books out of their general purses, but relied instead on donors – usually current or former members of the college – to stock their shelves.

Binding of the Pembroke Benefactors’ Book, 17th century, probably executed in Cambridge by the ‘Centre Rectangle Binder’

The Cambridge Digital Library has recently published a digitised and edited version of the Benefactors’ Book that Matthew Wren made for Pembroke College. It is a special example of the genre, because it includes a large amount of scholarly material in addition to its lists of book-donors. Wren, who served as the college’s president from 1616 to 1624, had undertaken a large project to remake the College library. Besides repairing its furniture, he reorganised the library’s medieval manuscripts, reconstructed its early history from surviving records, and prepared a list of its benefactors, both dead and living. In 1617 he recorded the fruits of all these labours in a single large folio-size book, which we now know as the Pembroke Benefactors’ Book.

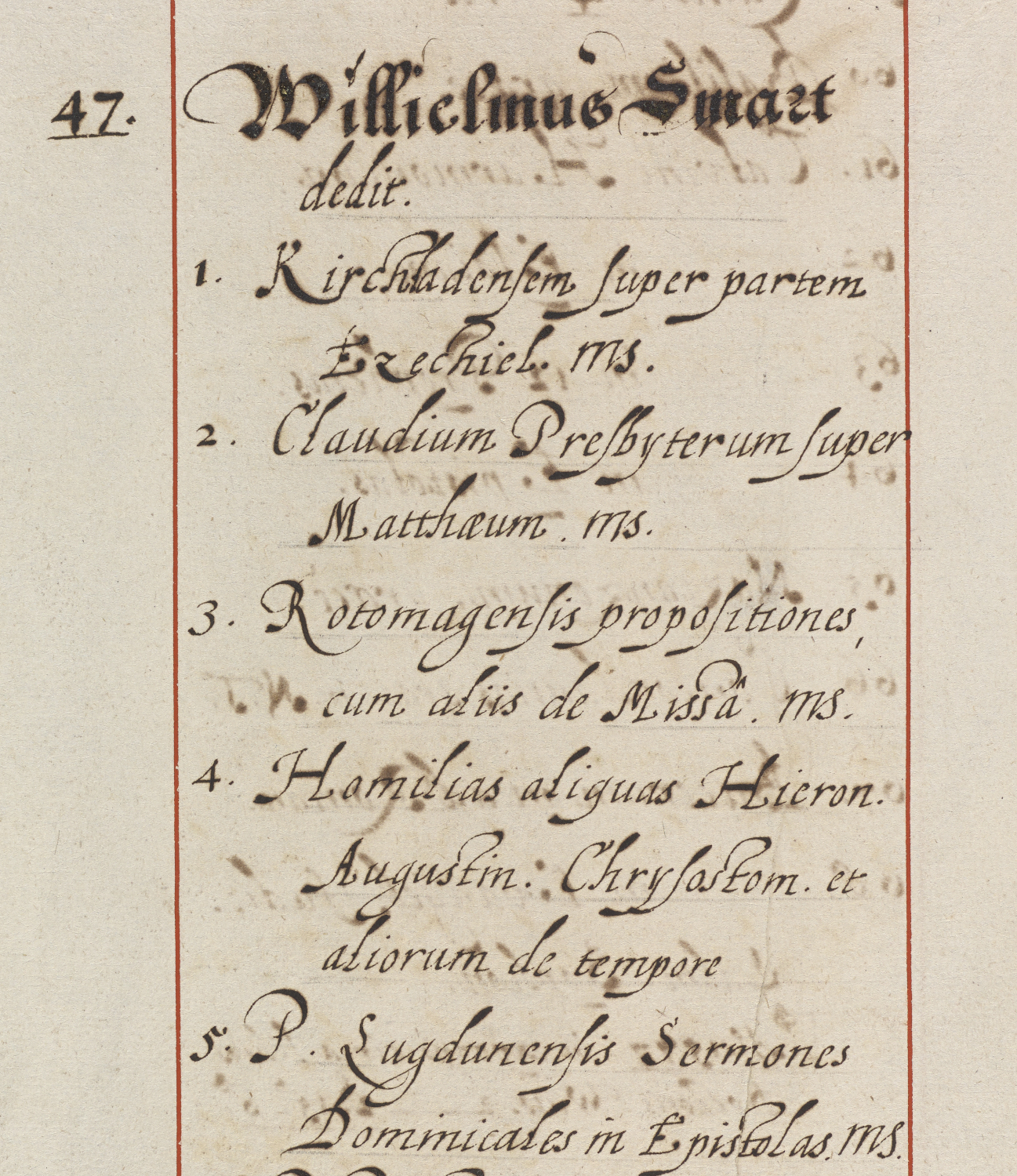

The manuscript is divided into three parts. The first contains Wren’s retrospective history of Pembroke’s library, which he based on some of the College library’s now-perished medieval records. Wren’s history is a remarkable example of early English bibliography, given the pains he took to reconstruct the shifting intentions of the library’s earliest users. In this section, Wren transcribed as many historical gifts to the library as he could find evidence for. The list is in many places unreliable: it records phantom books but omits real ones, and many of its attributions are erroneous. Nevertheless, it represents the best source we have for the early history of Pembroke’s library. Of great interest is Wren’s list of eighty books from the library of the dissolved Benedictine abbey at Bury St Edmunds, which were given to the College by William Smart in 1599.

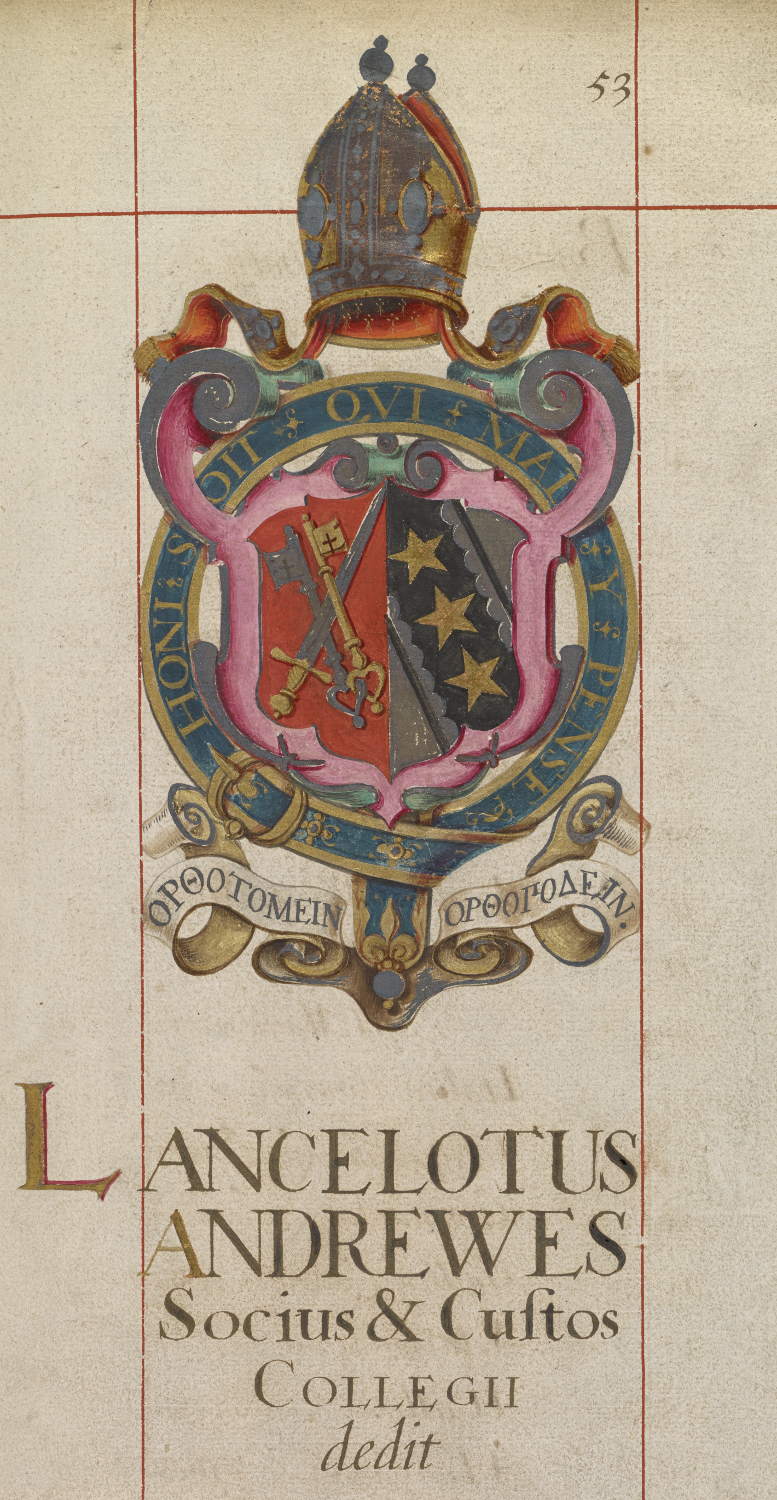

The second part records new gifts to the library, beginning with some made during Wren’s tenure and continuing well after his departure. At least one page is devoted to each benefactor, bearing the man’s arms, a eulogising biography, and a list of the books that he gave. The page of Lancelot Andrewes, Wren’s personal benefactor and a major donor, has by far the most lavishly painted coat of arms. (Ralph Brownrigg, Wren’s Puritan rival, was by contrast given neither arms nor eulogy on his own page).[1]

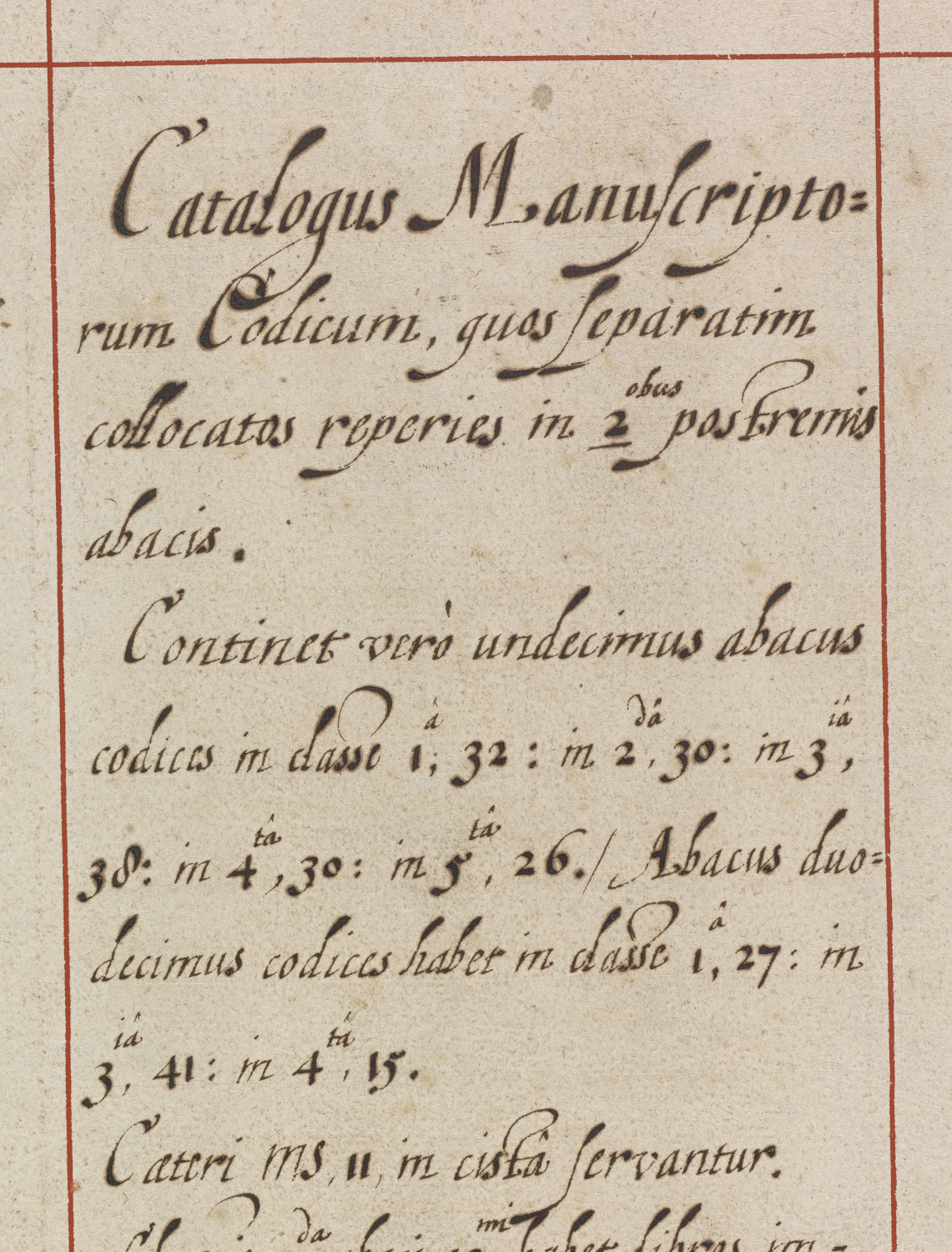

The third part is Wren’s catalogue of the manuscripts held by Pembroke library. Wren devised an innovative system of arrangement for these. Manuscripts were henceforth to be stored separately in two cabinets and a chest, and each book given three numbers, indicating the cabinet (abacus) it was stored in, the shelf (classis) on said cabinet, and its position along the shelf. Some manuscripts, meanwhile, were simply deposited in a large chest without any reference marks. Since many manuscripts contained works by many different authors, Wren provided two alphabetical indices in which a book or author could be looked up. One was list of volumes, alphabetised to the first author’s name. This list gave each manuscript’s classmark. The other list was a mix of all the authors and books that could be found in any volume, and was cross-referenced to the first list. A reader looking for works by Jean Gerson, for example, could look up his name under G in the second index, and be led to the position A7 in the first. There, at the seventh entry under the letter A, he would find the volume he needed, with the classmark 11.4.11. Then he could go to the eleventh cabinet, count to the eleventh book on the fourth shelf, and find his book.

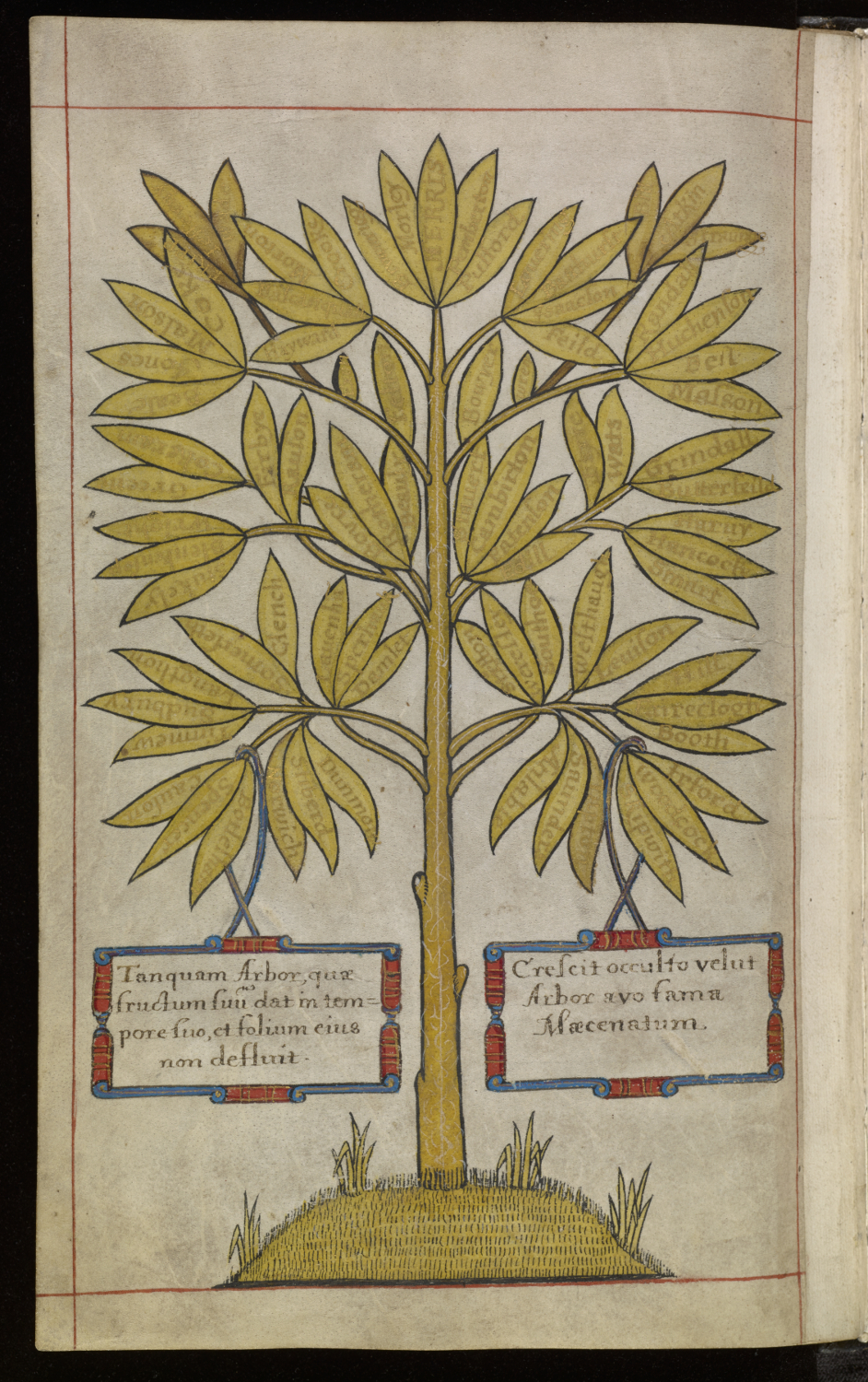

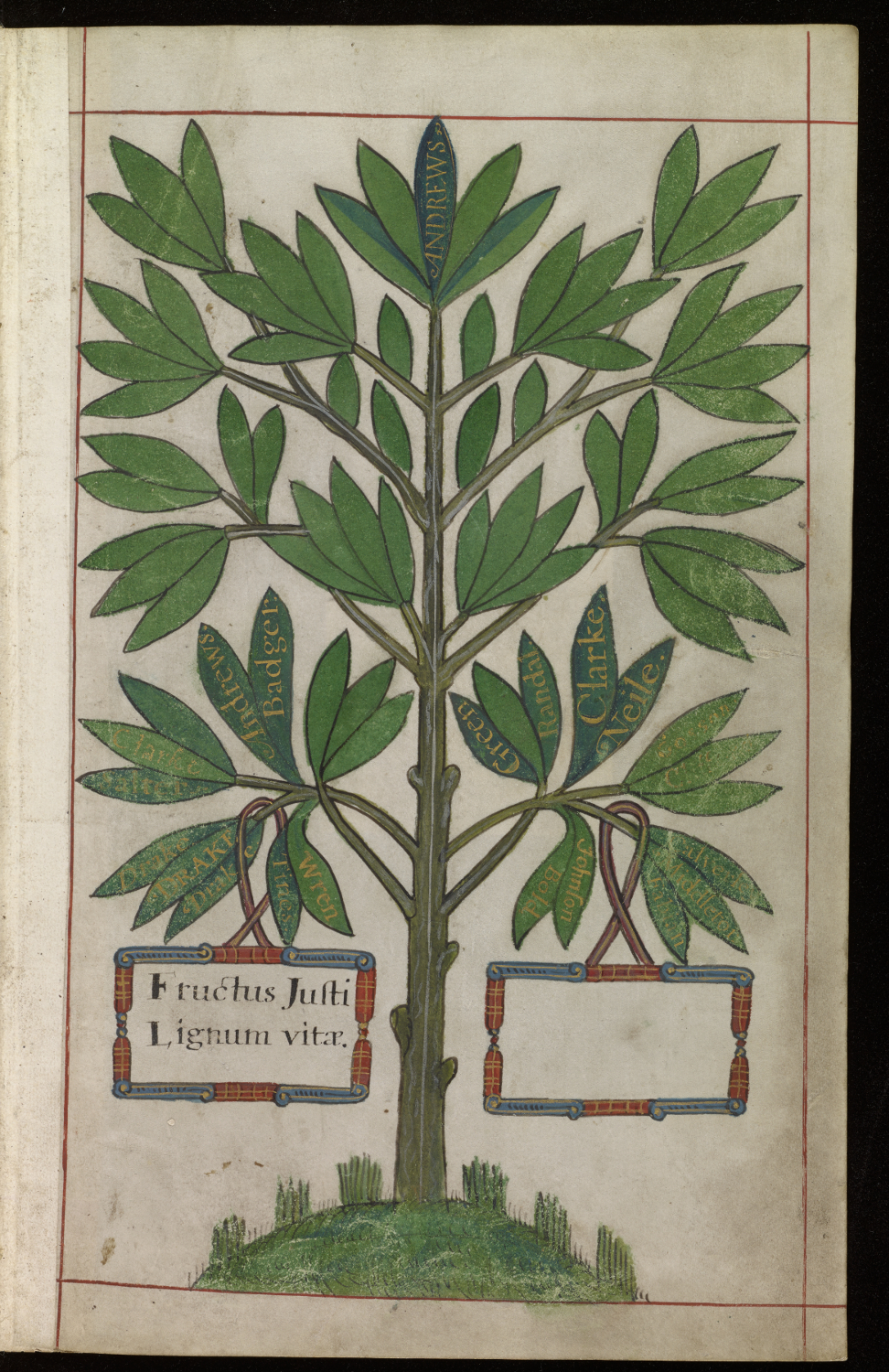

At the front of the Benefactors’ Book is an ornate frontispiece. Two trees are painted on facing pages, one bearing gold leaves and the other green. The gold tree’s leaves sport the names of the library’s deceased donors, and the green tree’s are reserved for living benefactors. Many of its blank leaves are suggestively blank, as if waiting to be filled in. This frontispiece gives us the key to the ultimate purpose of the Benefactors’ Book: it was an instrument for encouraging donations of books to Pembroke’s library. By bequeathing a book or collection of books, a former member of the college could repay the academic community that had nourished him. All the better, from his perspective, if his name could be memorialised in so sumptuous a book.

In 1622, the Pembroke fellow Richard Pemberton attached the following inscription to the book he gave, which was later copied into his entry in the college benefactors’ book. It is a poem of thanksgiving to Marie de St Pol, foundress of the College:

Ω φιλὴ Μαριὰμ Μαρίαν μετὰ παρθένον ἁγνὴν

Ου σ᾽ ἀν ἀμειψαίμην πρὸς Αθῆνας μητέρα κεδνὴν

Ευμενέως λάβε ταῦτα τεοῦ θρεπτήρια τέκνου,

Quem res curta satis non sinit esse pium.

(O fond Marie, next in worth to the holy virgin Mary,

Though I cannot repay thee, fosteress of Athens,

Take with good will your son’s offering of thanks for his nourishment,

Whose poverty keeps him from sufficient piety.)

There are a thousand similar sentiments in most of the donors’ books. The books that a donor gave declared his thanks to – and his membership of – the intellectual family that had brought him up. The Pembroke Benefactors’ Book itself was created in the same spirit of filial reverence. In his opening letter to the Master and Fellows, Wren offered them his labours as an act ‘of thanksgiving to our forebears, of devotion to alma mater, of duty to you, and of encouragement to posterity.’

Whether the benefactors’ book succeeded in its purpose of actually encouraging donations to the library is an open question. It can be said for certain, however, that it succeeded in commemorating Pembroke’s seventeenth-century donors. Indeed, Pembroke’s benefactors’ book is one of our most important material witnesses to a learned society that is now sunk far into the past.

Notes:

[1] Ralph Brownrigg featured briefly in an earlier blog post concerning the provenance of a notebook containing an early draft of part of the King James Bible.