‘Truth-Untruth’: Brexit through letterpress

This post is by Alan Qualtrough, a letterpress artist, graphic designer and typographer based in Plymouth who met two of the Library’s staff at a conference on letterpress printing at Leeds University in the summer. He kindly offered to present the Library with one of two copies of a letterpress book produced for his MA, since it concerns Brexit, a subject actively collected in the Rare Books Department.

The book Truth – Untruth was part of my MA research and considered whether the materiality of letterpress could interrogate the production and consumption of digital communications to understand how truth is established or subverted. As a former newspaper editor and reporter, I was particularly interested in how fake news was produced and circulated virally during the Brexit campaign, especially by newspapers, and the poor standard of journalism that some media upheld.

The book Truth – Untruth was part of my MA research and considered whether the materiality of letterpress could interrogate the production and consumption of digital communications to understand how truth is established or subverted. As a former newspaper editor and reporter, I was particularly interested in how fake news was produced and circulated virally during the Brexit campaign, especially by newspapers, and the poor standard of journalism that some media upheld.

It is said we live in a ‘post-truth’ society in which debate is framed by argument that pays  no attention to truth or established and agreed facts, and one in which most of us use cut and paste to share information (or misinformation) virally. There is also growing evidence that reading digital content on the web changes the brain’s neural circuitry, which was developed for deep reading.

no attention to truth or established and agreed facts, and one in which most of us use cut and paste to share information (or misinformation) virally. There is also growing evidence that reading digital content on the web changes the brain’s neural circuitry, which was developed for deep reading.

When we skim read digital content (as opposed to deep reading of print content) it adversely influences the quality of our most important intellectual processes causing subtle atrophy of critical analysis which leaves us susceptible to false information and ultimately threatening democracy.

My MA programme considered whether the recontextualising of language into letterpress form and the materiality of letterpress itself—especially touch and the time process required—can help identify fake news and encourage deeper engagement with language. It is possible that the slowness of the letterpress process creates a personal space and critical ecosystem for the practitioner to have an engagement with language, allowing a critical approach in a way that the digital process cannot emulate. The way I tried to explore these theories was through a series of interventions produced as art works.

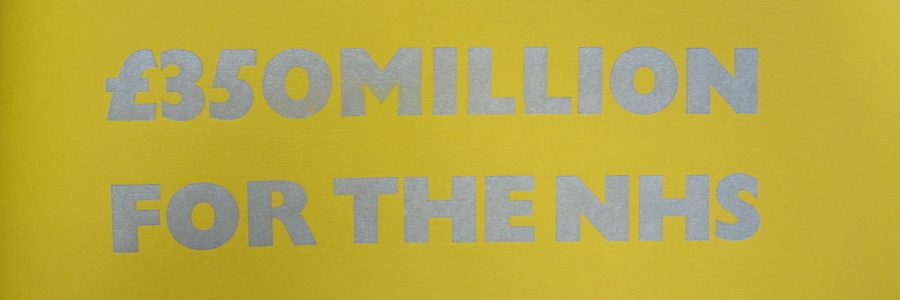

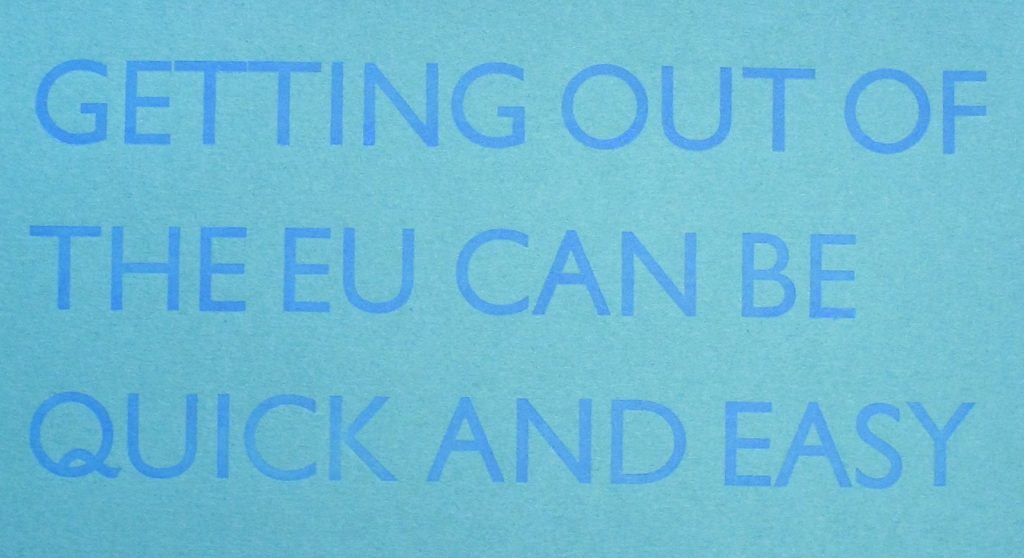

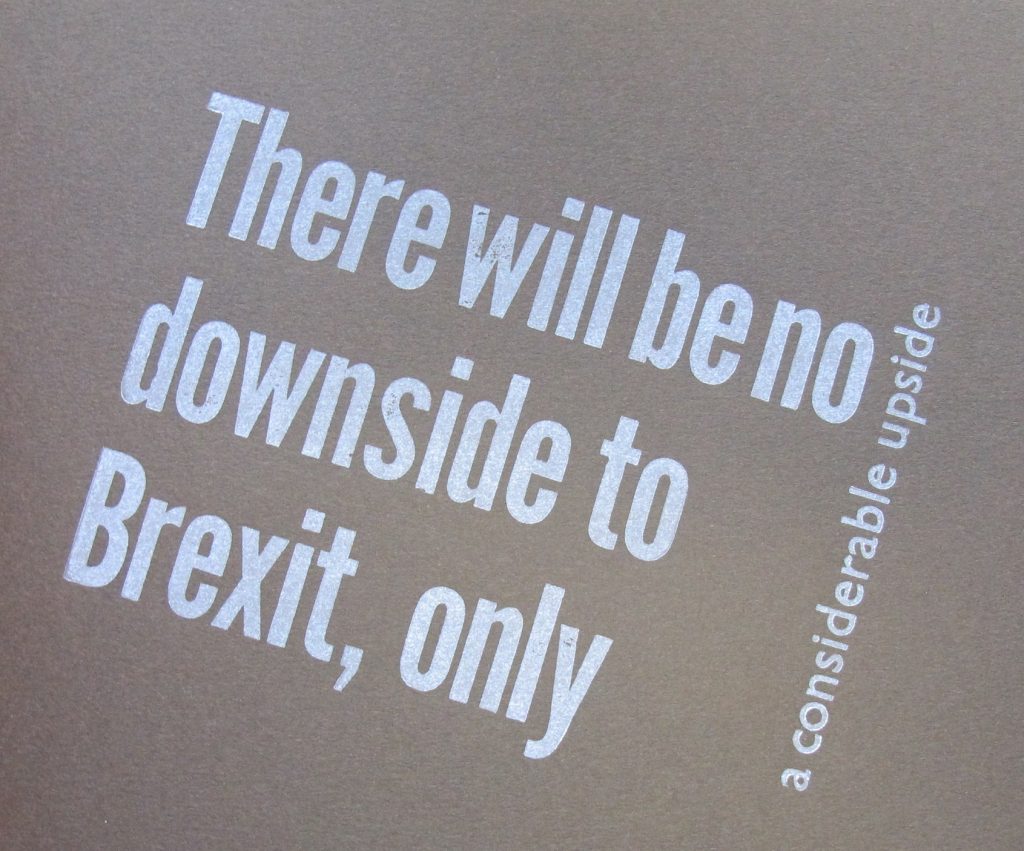

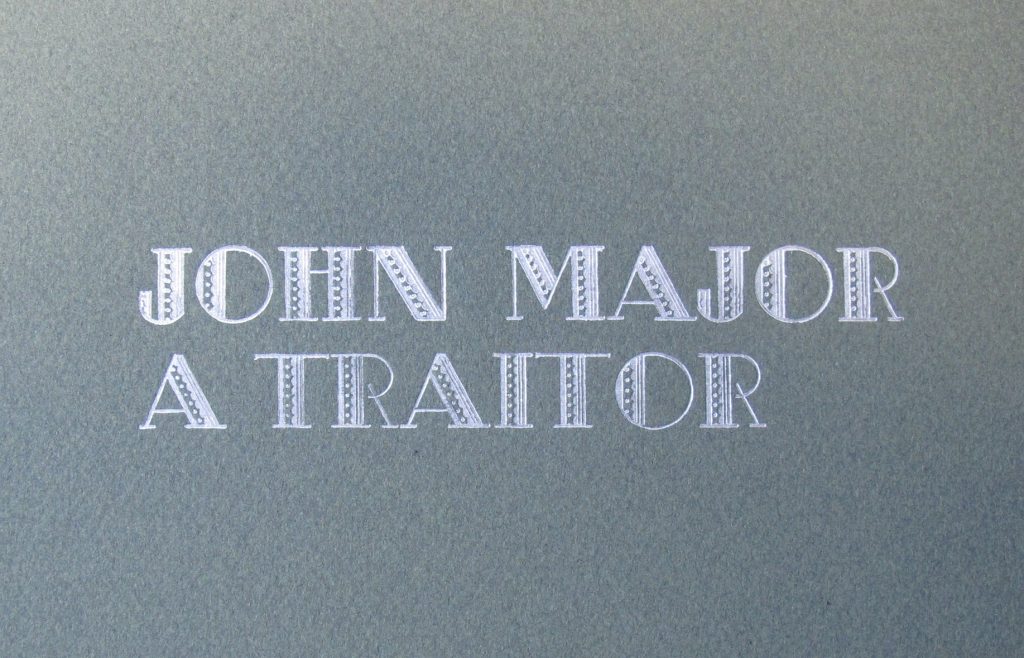

Truth – Untruth, recently presented to Cambridge University Library and from which the illustrations in this blog are taken, was one of those outcomes. It is composed of fifty Brexit lies, each page handset using moveable type, printed on a 1960s FAG Control 405 Swiss-made press, and then hand-bound. The words were produced in different fonts, positioned in different orientations and printed on a variety of substrates to reinforce the effect of them being out of context. The touch and materiality of the printed book can be compared with the same content online.

Truth – Untruth, recently presented to Cambridge University Library and from which the illustrations in this blog are taken, was one of those outcomes. It is composed of fifty Brexit lies, each page handset using moveable type, printed on a 1960s FAG Control 405 Swiss-made press, and then hand-bound. The words were produced in different fonts, positioned in different orientations and printed on a variety of substrates to reinforce the effect of them being out of context. The touch and materiality of the printed book can be compared with the same content online.

Additional leaves of Truth – Untruth were used in a conceptual collage to create a parallel reality of the way I think the Brexit process has been driven by an ideology which disguises itself as democracy. In addition, using letterpress as performance, I interviewed people about Brexit, typed their answers on spare leaves of the book, shredded the pages, then cut and paste the shredded words onto an image of Article 50, printed digitally on camouflage colours—a metaphor for the way the Government had ignored the growing protest to Brexit. The piece entitled Crypsis Mimesis, measuring 1,188 mm by 1,050 mm, has been bought by Plymouth College of Art for its collection.

A central theme of the project which was completed at Plymouth College of Art was the words of the distinguished philosopher and journalist Walter Lippmann who wrote in 1920: ‘There can be no liberty for a community which cannot detect lies.’ Writing nearly a century ago, Lippmann maintained that a society needs pure unbiased information for the proper running of democracy, an argument I agree with.

Alan’s book, Truth – Untruth, is available to readers in the Rare Books Reading Room at the shelfmark CCA.69.22, as part of a collection of books and ephemera on Brexit.