‘Thousands of little loose papers without any order at all’: Material signs and afterlives in the UL’s earliest Arabic acquisitions

In the second in a series of guest posts by UL researchers, Samantha Brown shares her work on the materiality and afterlives of the manuscripts of the seventeenth-century Arabist William Bedwell, the subject of her dissertation for the MA in Early Modern Studies at UCL. Samantha is hoping to return to UCL in September to begin a PhD that will build on this research.

The first item I ever called up at the UL’s Manuscripts Reading Room was a weighty leather-bound volume that goes by the shelfmark Hh.5.1. Having read about it in books and blogs I knew that it was part of a seven-volume Arabic dictionary in folio, the lifework of its creator, the clergyman and scholar William Bedwell (1563-1632).[i] I also knew that, having found its way to the university after his death in 1632, it was one of the first Arabic manuscripts in the library’s collection.[ii] However, as many frequent archive-goers will know, no amount of reading prepares you for getting your hands on the real thing. In the case of Hh.5.1 that meant being immediately struck by its sheer bulk, the way Bedwell’s growing linguistic knowledge fights for space within its pages, and how seeing it in the flesh sheds light on contemporary descriptions and events. My research focuses on the afterlives and materiality of Bedwell’s manuscripts, which have been scattered across multiple British and European institutions, and nowhere do these two factors combine more tangibly than at the UL.

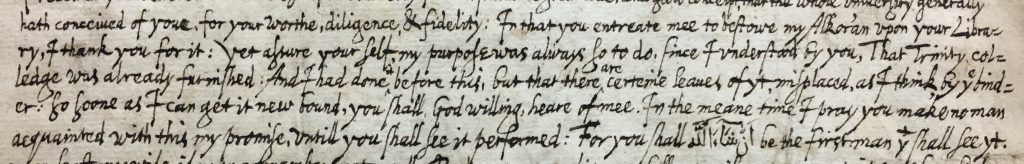

The story of Bedwell and the Cambridge University Library begins in October 1630, when he wrote to his friend, fellow Arabist and then Keeper of the Library, Abraham Wheelock, concerning a different Arabic manuscript: Bedwell’s modest undated copy of the Qur’an:

In that you entreat me to bestow my Alkoran upon your Library, I thank you for it: Yet assure your self, my purpose was always so to do, since I understood by you, that Trinity college was already furnished. And I had done it before this, but that there are certain leaves of it misplaced, as I think by the binder. So soon as I can get it new bound, you shall, God willing, hear of me.[iii]

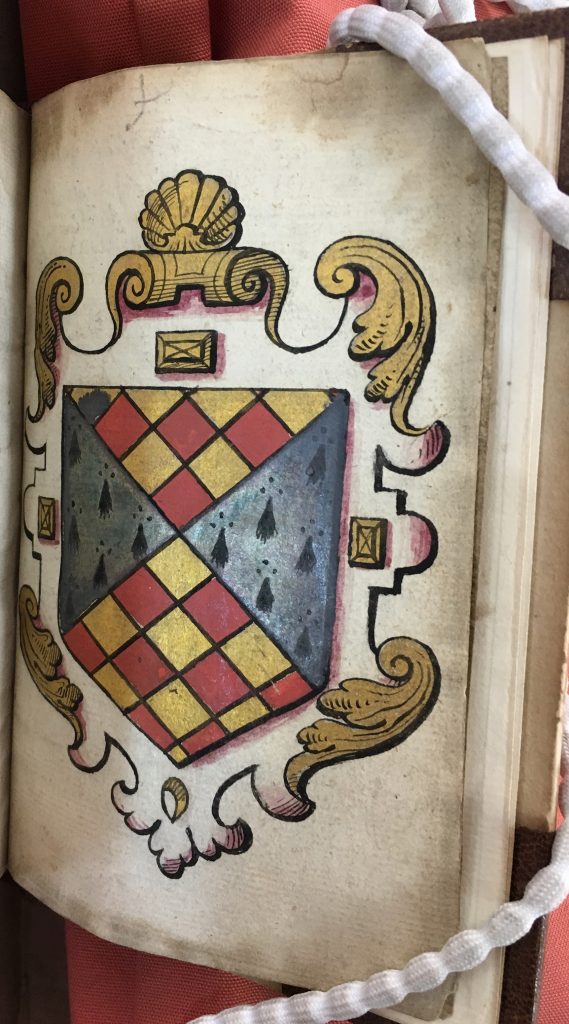

While discussing his first Arabic acquisition with Bedwell, Wheelock was also in negotiations with the wealthy merchant Sir Thomas Adams regarding the establishment of Cambridge’s Arabic professorship – a role he himself was lined up to fill. Arabic texts were rare and valuable in England at the time, and Wheelock was presumably mindful that languages are very difficult to teach or learn without physical resources. Bedwell kept his word and his Qur’an made its way to Cambridge in 1631.[iv] He is identified as its donor by an inscription written by Wheelock, and a full page is dedicated to the hand-painted Bedwell coat of arms. It is tempting to imagine Bedwell arranging this ownership mark with his binder, or perhaps carefully undertaking the task himself, ensuring that he and his much sought-after manuscript would forever be linked.

Bedwell’s arms in his Qur’an (Ii.6.48)

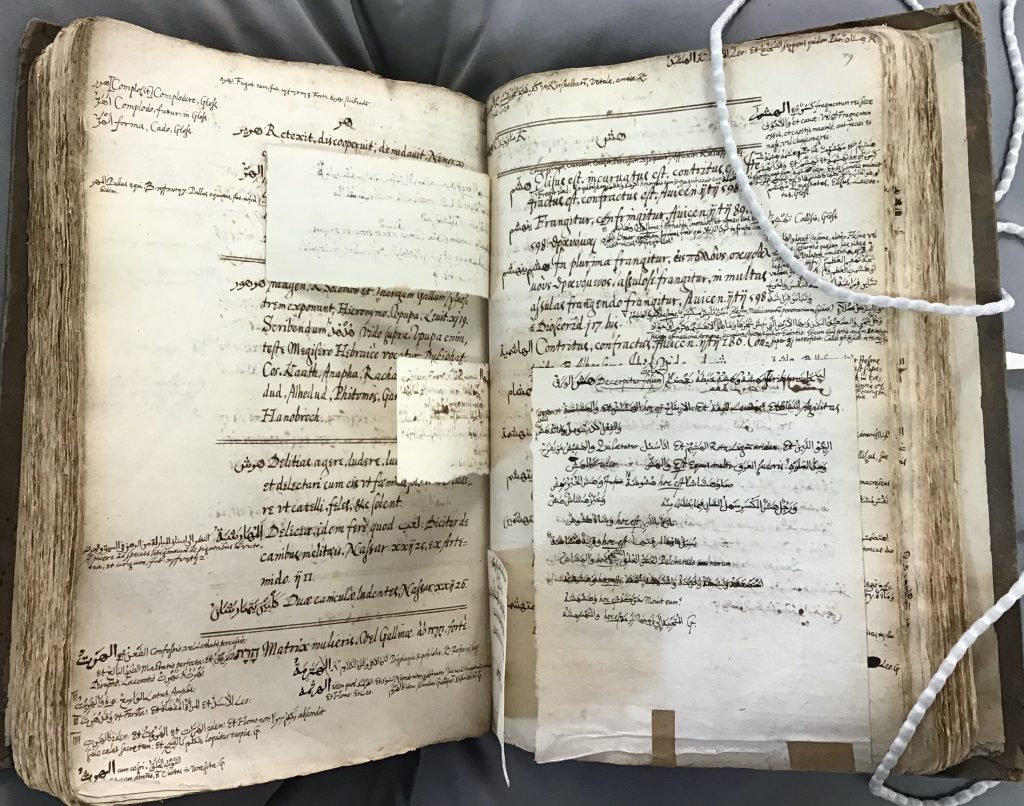

Bedwell’s dictionary (MS Hh.5.7)

So, when Bedwell died on 5 May 1632 his Qur’an was already in Cambridge, but the fate of his multivolume manuscript dictionary was less than certain. Letters to Wheelock from Adams and Bedwell’s son-in-law, John Clarke, reveal the tensions surrounding the bequest. At first, Clarke informs Wheelock that the dictionary is the University’s, as long as they promise to fulfil Bedwell’s wish of seeing it in print. If they will not, he suggests the manuscripts should go to somebody who will endeavour to print them, and he would instead provide the university with a copy of the resulting book. Not only would this secure Bedwell’s legacy, but it would also ensure the safety of the dictionary itself, which risked being ‘tossed & torn in the Library… and there be many loose papers in it, which will be misplaced & lost’. Adams then confuses matters, repeating rumours concerning the contents of Bedwell’s will: that it is Trinity College, not the University Library, who will benefit from his gift. Clarke is swift to rebut this misinformation, as‘the words of the will run thus. I give my Arabicke Dictionary to the university of Cambridge’.[v] Bedwell’s intentions for his dictionary finally being established, the next problems to arise were logistical:

The weather hath been so uncertain & the way is yet foul, that I have no desire to come out. Besides my mother hath multitude of business which as yet I have not dispatched, but so quickly as the weather sets in fair & business a little over, I will point you a day when to meet you. I pray you send word whether I shall give order for a [Joiner] to make a box for them & whether I shall take order with a Wagoner for their carriage.

Clarke to Wheelock, 31 August 1632

Autumn arrived and the deal was yet to be finalised. In October, Adams visited Clarke in a bid to speed up the dictionary’s move to Cambridge, but by November there was still no sign of its arrival. Adams could barely disguise his frustration, writing to Wheelock ‘I perceive Mr Clarke hath greatly failed in the discharge of his word with me, as he formerly hath done with you…’. The donation finally reached Cambridge at some point before the end of the 1632-3 academic year and, despite John Clarke’s pleas, the dictionary was never printed: the lack of functional Arabic type or capable compositors, combined with its length and complexity, made it an impossible task.

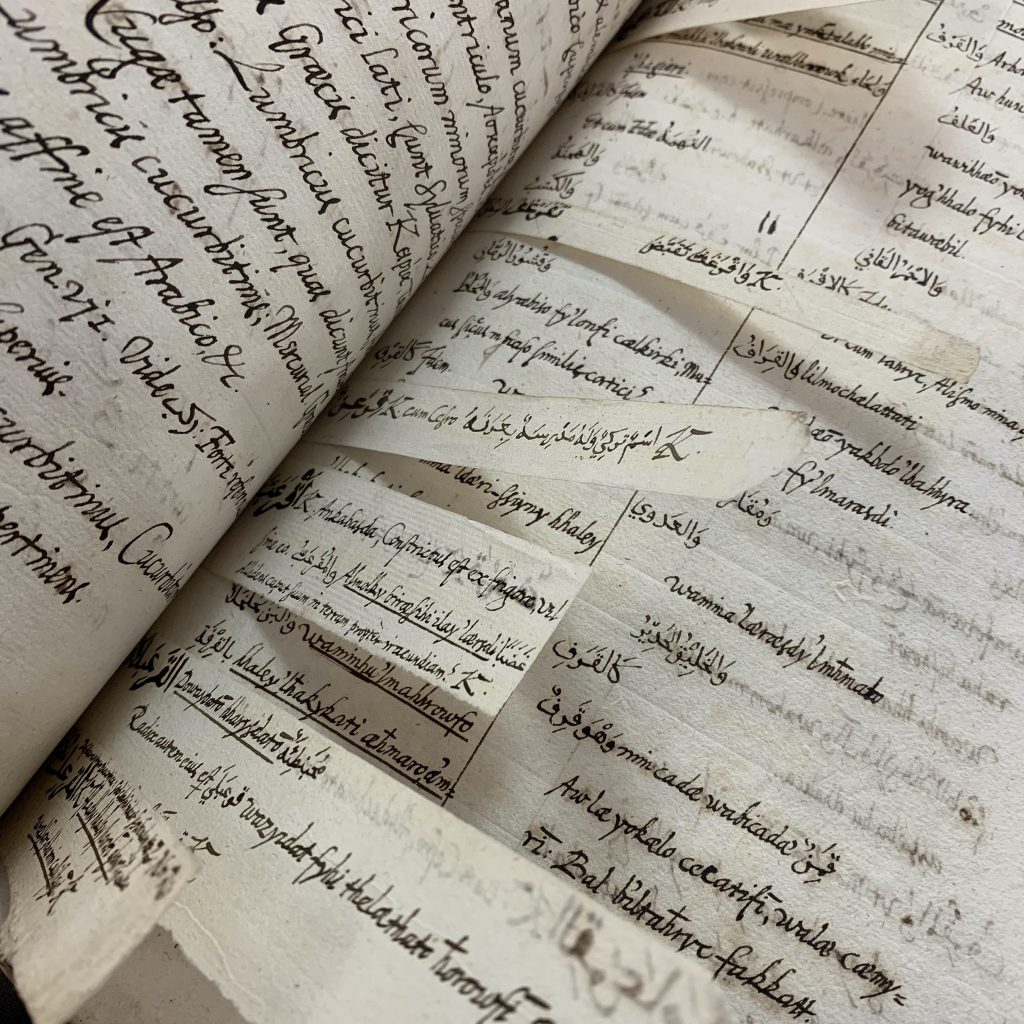

It was only upon seeing the dictionary for the first time that I really appreciated the enormity of any project to transfer it to print. The loose sheets of paper that Clarke feared would be ‘misplaced and lost’ (now affixed to their relevant pages, when and by who I am unsure) were evidently one of the greatest barriers to the dictionary’s publication. When Edmund Castell borrowed it in the late 1650s while compiling his own Lexicon Heptaglotton he was not impressed with its material form, which featured ‘so many hundreds some thousands of little loose papers without any order at all scatteringly inserted and some in worse order stitched together’. His assessment of the linguistic knowledge contained within it was equally scathing, as ‘Infinite are the words of which the great Bedwell almost in every leaf professes himself ignorant’.[vi]

Castell was not the first, or last, person to question Bedwell’s linguistic abilities, but I don’t believe this necessarily diminishes his achievements. With no time-tested methods and few original sources to hand, the study of Arabic in England was in its infancy. Confronted with new vocabulary and alternative definitions every time he encountered a previously unseen Arabic text, Bedwell’s understanding of the language appears to frequently shift and evolve. This scholarly process physically manifests itself through the expansion of his work, first into the margins, before spilling onto the many post-it like slips that embellish the dictionary’s pages. The chaotic material form of his dictionary embodies Bedwell’s lifelong quest to piece together this linguistic puzzle, and, for me at least, represents his status as a pioneer who paved the way for the scholars of Arabic who followed.

[i] A. Hamilton, William Bedwell the Arabist: 1563-1632 (Leiden, 1985).

[ii] Bedwell’s bequest contained not just his seven-volume folio dictionary (MSS Hh.5.1-7), but also the first two volumes of an unfinished quarto dictionary (MSS Hh.6.1-2), and the Arabic equipment he hoped could be used to print his work (now lost).

[iii] All the letters to Wheelock I mention are found in MS Dd.3.12, unless otherwise stated.

[iv] CUL MS Ii.6.48.

[v] Transcribed in BL Harley MS 7041.

[vi] G. J. Toomer, Eastern Wisedome and Learning: The Study of Arabic in Seventeenth-century England (Oxford, 1996), p. 63.

I’m looking for a picture of Abraham Wheelock. May you help me with that, please?

Unfortunately, there’s no known portrait of Abraham Wheelock, as Catherine mentions in this blogpost: https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=15805

Best wishes,

Suzanne Paul

Keeper of Rare Books and Early Manuscripts, CUL