William Morris & the book

To mark the 125th anniversary of the publication of William Morris’s edition of the works of Chaucer, 26th June has been designated ‘International Kelmscott Press Day’ by the William Morris Society in the USA. The Library is lucky to hold extensive collections relating to Morris, including books from his workshop and typographical equipment as part of its Historical Printing Room collections. This month seems like a good time to delve a little deeper into these items.

Morris was born in 1834 and began to be strongly influenced by medievalism during his time at Oxford University in the 1850s. As part of the Birmingham Set (a group at Oxford which played a significant part in the Arts & Crafts movement) Morris met Edward Burne-Jones and a number of other individuals with interests in the visual arts with whom he would go on to work (Burne-Jones contributed 87 woodcut images to the Kelmscott Chaucer of 1896). He went on to become known for his furniture, stained glass, wallpaper and – towards the end of his life – for his efforts to bring beauty back to the world of book production. Until the beginning of the nineteenth century printing books was a job done entirely by hand, using presses little changed in their design for centuries. But with increasing mechanization the process leaned more towards efficiency and speed rather than beauty. As a collector of medieval manuscripts and early printed books Morris was influenced by the great attention paid by their creators to lettering, type design, imagery and binding. In a paper given to The Bibliographical Society in 1893 (entitled The Ideal Book) Morris noted that ‘ornament must form as much a part of the page as the type itself, or it will miss its mark, and in order to succeed, and to be ornament, it must submit to certain limitations, and become

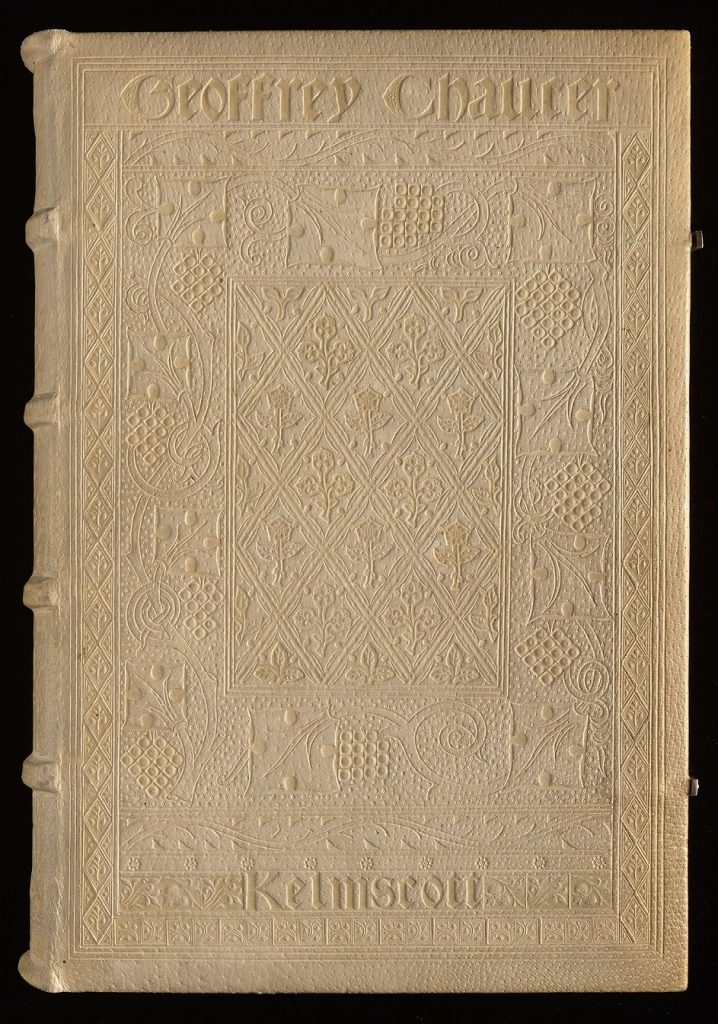

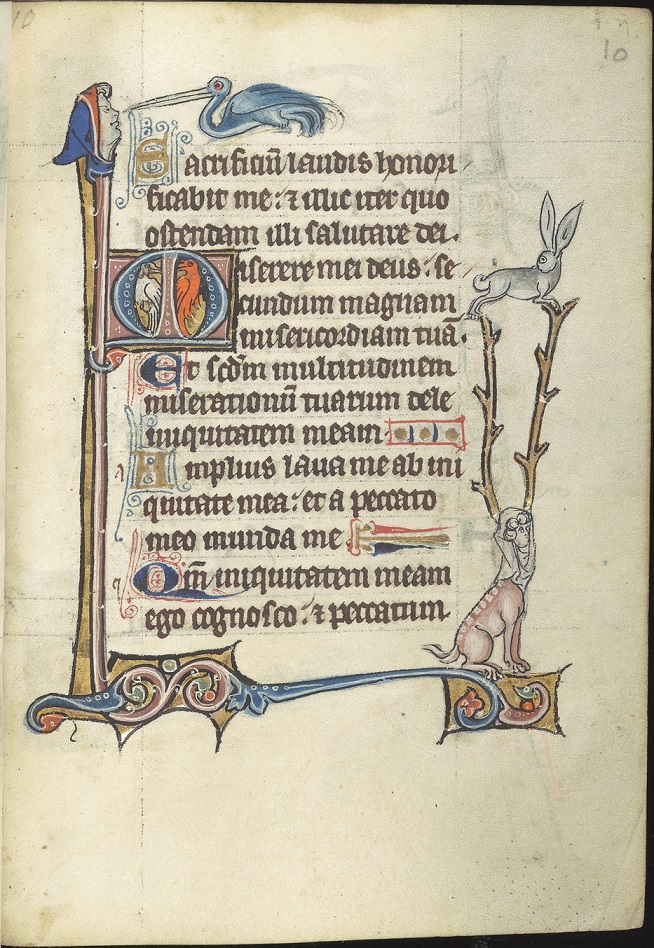

architectural.’ One book narrowly missed by Morris at auction in 1893 (instead sold to collector Samuel Sandars and in 1894 bequeathed to the Library) shows the sort of medieval design that inspired him: a Psalter made in Flanders c. 1300 (above right). Another manuscript which Morris did succeed in acquiring – a pocket Paris Bible of c. 1225-50 (Add. 6159) full of jewel-like historiated initials – came to the Library in 1918, having been presented by John Charrington. From 1891 to 1896 Morris’s press produced some fifty-three titles in something like 22,000 copies, from slim volumes to huge folios. Buyers had a number of options when it came to buying Morris’s books. The Chaucer, for example, was printed in 425 copies retailing at £20 each. A small number (13) were printed on vellum and cost a staggering £126, including our copy (Sel.1.16, which also came as a gift from John Charrington in 1918), which was bound in wooden boards and stamped leather imitating the medieval style (above left).

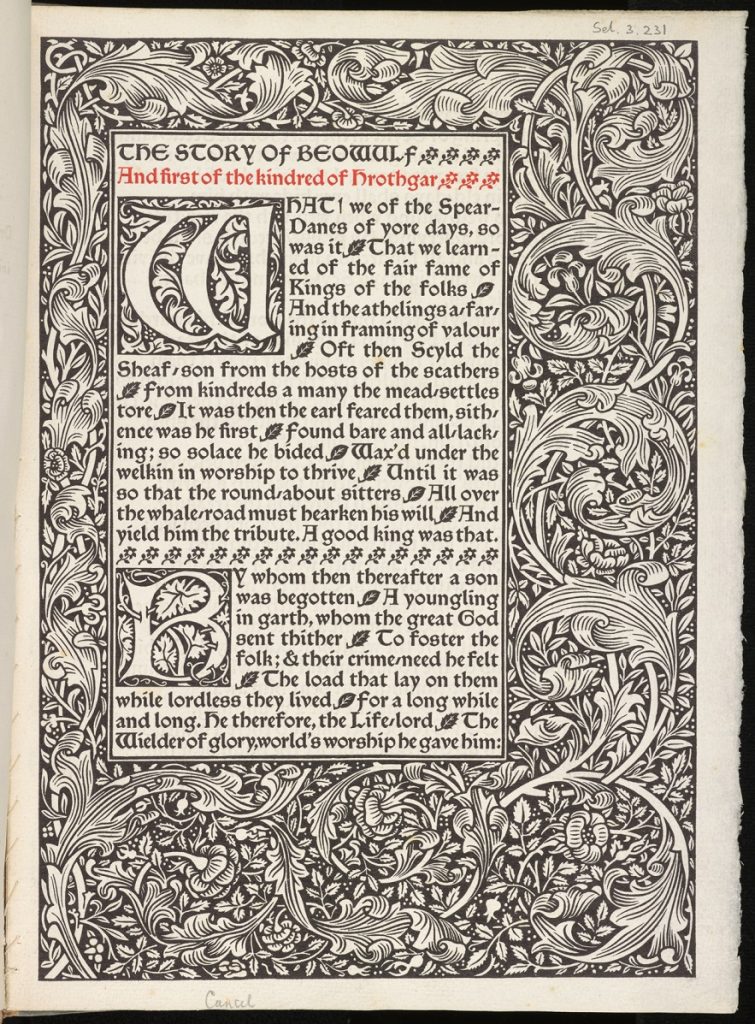

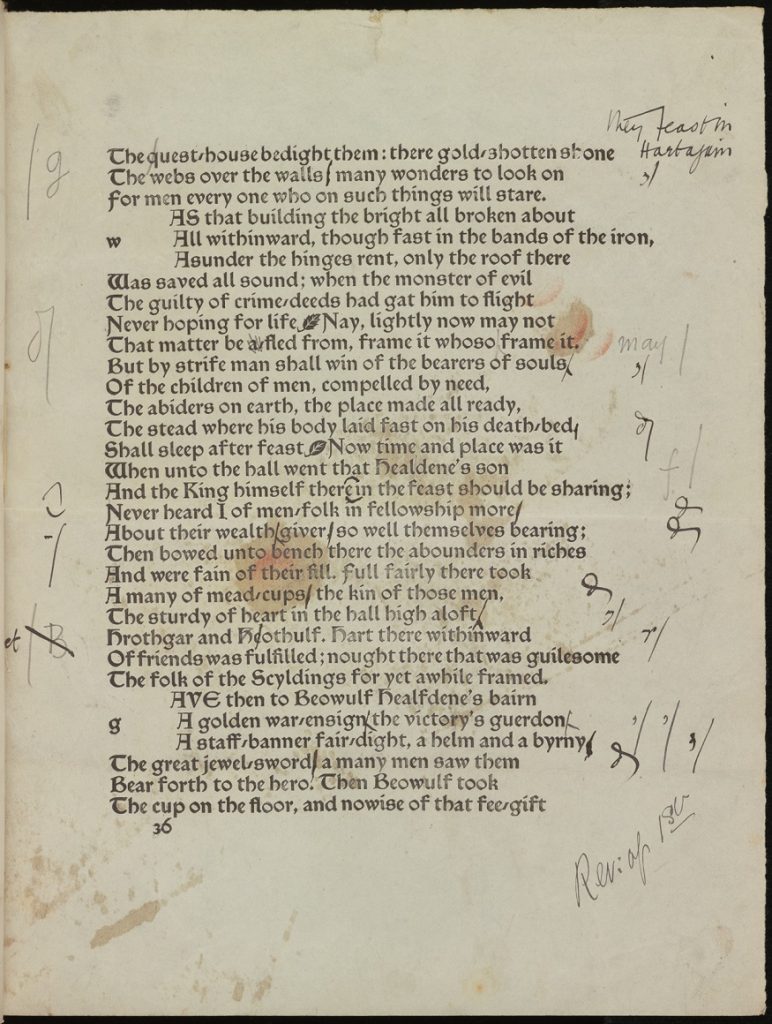

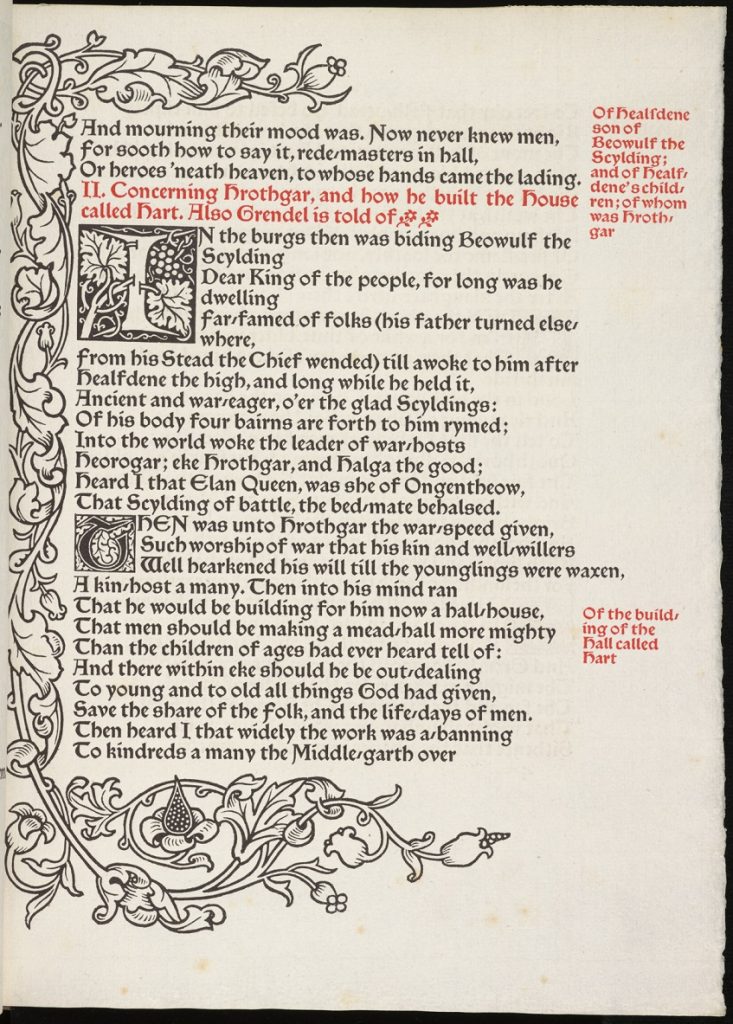

One of the more interesting copies of a Kelmscott book held at the University Library is a set of proof sheets of the edition of the Old English epic poem Beowulf (1895), presented to the Library in 1904 and now fully digitised on the Cambridge Digital Library. The text derived from oral tradition, telling the tale of Beowulf, a mythical warrior hero who slayed the monster Grendel by tearing off its arm, dispatching Grendel’s vengeful mother, and finally, much later and advanced in years, being killed by a dragon. William Morris described it as ‘the first and the best poem of the English race’. It survived into modern times through a single manuscript (nearly lost in a fire in 1731), thought to date from the early eleventh century and now (via the collection of Sir Robert Cotton) in the British Library. A Cambridge connection is provided by the fact that Morris was assisted in his translation by the Christ’s College scholar of Anglo Saxon, Alfred Wyatt, Morris versifying Wyatt’s literal account. The proofs – whose decorative borders and initials show Morris’s medieval inspiration from books like the psalter above – bear extensive annotations and corrections in Morris’s hand (see above centre).

The proofs had been in the possession of Robert Proctor, a bibliographer at the British Museum who worked extensively on early printed books. Proctor met Morris in 1894 and was both an avid collector of Kelmscott books and nurtured interests in areas in which Morris chose to publish (like Morris, Proctor worked on translations of Icelandic sagas). He even served as an executor of Morris’s estate. It is not known how the Beowulf proofs came into Proctor’s hands; he may have advised Morris on aspects of its production, or he may have acquired it through one of their mutual friends like Sydney Cockerell (from 1908 Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum) or Emery Walker. Tragically Proctor never returned from a walking holiday in the Austrian Alps in 1903 and in the following year his mother presented the proofs to the Library in memory both of her son and of Morris, as shown by her inscription and Proctor’s bookplate inside.

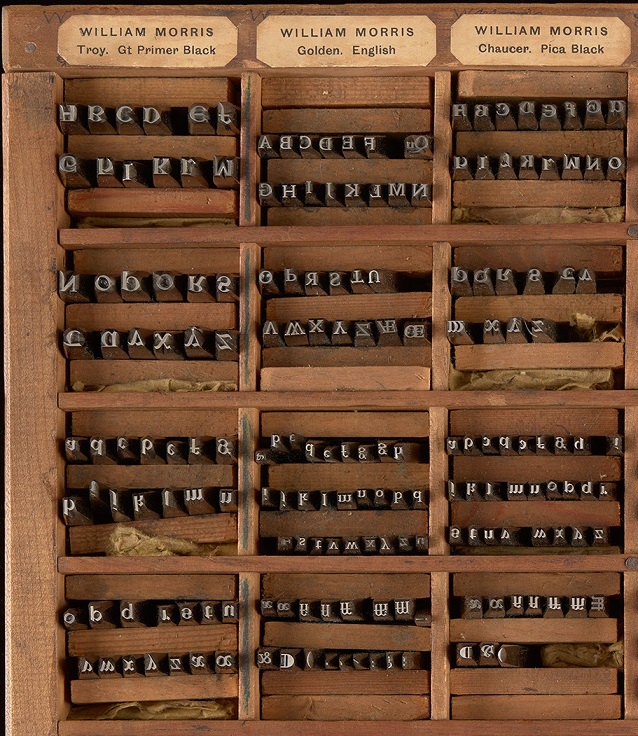

The typographical equipment pictured above is part of a collection of Kelmscott material acquired by Cambridge University Press in 1940 and since deposited with us. These include the punches and matrices for his Troy, Chaucer and Golden types, cases of type for each face, two of the wood and brass paper moulds made specially for Morris’s use and a small stock of his ‘Flower’ paper (used for special occasions, including a keepsake to mark the visit of Cambridge’s new Vice-Chancellor in 2017), named from the watermark which appears on each sheet (see below). Punches (steel rods onto one end of which a letter was carved) and matrices (soft pieces of copper into which the letter on the punch was hammered) are the building blocks for making type, and more information on the processes involved can be found online. These sit alongside extensive typographical collections held by the Library, including the eighteenth-century punches for John Baskerville’s type, the Brook type from the Eragny Press, punches for the Subiaco and Ptolemy types used by the Ashendene Press (one of many presses founded in the wake of Morris’s efforts), and and punches for Eric Gill’s Perpetua and Joanna types.

One hundred and twenty five years after the publication of Morris’s edition of Chaucer, and one hundred and thirty years after the foundation of his Kelmscott Press, interest in his ‘typographical adventure’, as he called it, remains high. Collectors still seek out his books and libraries continue to acquire them, to tell the story of one man’s campaign to bring beauty back to the world of book production.

Thank you for your observation. R. David Weaver

Thanks

As a writer and amateur collector of Kelmscott Press books, I’m so excited by the introduction of an International Kelmscott Press day, in recognition of William Morris’ significant contributions to modern printing. Thank you for sharing your collections with a wider audience than might otherwise be exposed to Kelmscott Press collections and ephemera. The photos were wonderfully done. By sheer coincidence, earlier today I had been wonder how watermarks were applied to handmade paper, such as the Bachelors Paper employed by Morris, and then I saw the photograph above of the ‘Kelmscott Press paper mould in wood & brass;’ and I serendipitous learned the answer to my musings.

Thank you for sharing and participating.

Thank you for your kind words! Glad this was interesting.

I am an art historian. A member of the U3A I am giving a presentation next week on Flowers in Pre-Raphaelite and Symbolism Art. I have a few William Morris, Burne-Jones Kelmscott press books. Copies of course. Thank you for this information. I love books.