Grace Chisholm Young (1868-1944), Girton mathematician

In the Rare Books Department we receive many catalogues from booksellers and auctioneers, offering materials which might be added to our shelves. One such catalogue in recent months contained the apparently uniquely surviving copy of an 1895 PhD thesis in mathematics, the first PhD awarded in Germany to a woman, all the more interesting to us as the recipient – Grace Chisholm Young – had Cambridge connections. The stories of a number of women like Grace was told in our 2020 exhibition ‘The Rising Tide: Women at Cambridge‘ and as such we are always keen to add to our holdings in this area. As so often is the case, a search on our shelves turned up a copy (as well as copies at Girton & the Institute of Astronomy), since the Library has extensive collections of academic theses awarded by non-UK institutions. But the majority are catalogued only on cards, not online, and are arranged by institution, necessitating lengthy searches at the shelf, a search which in this case saved us over £3000. It is now catalogued and available to readers in the Rare Books Room.

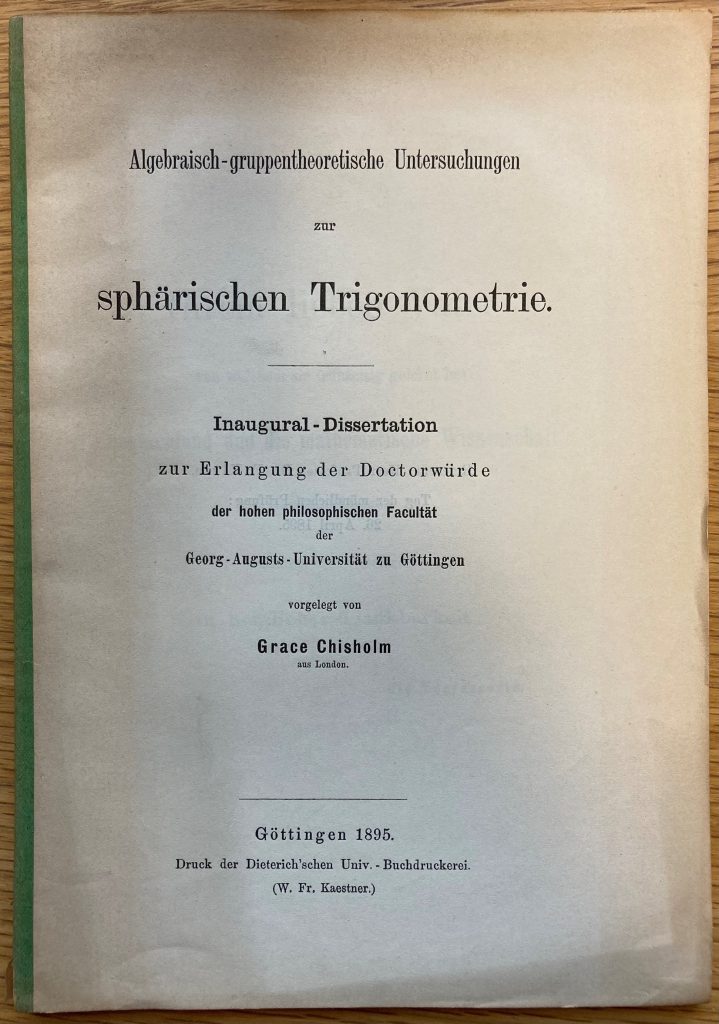

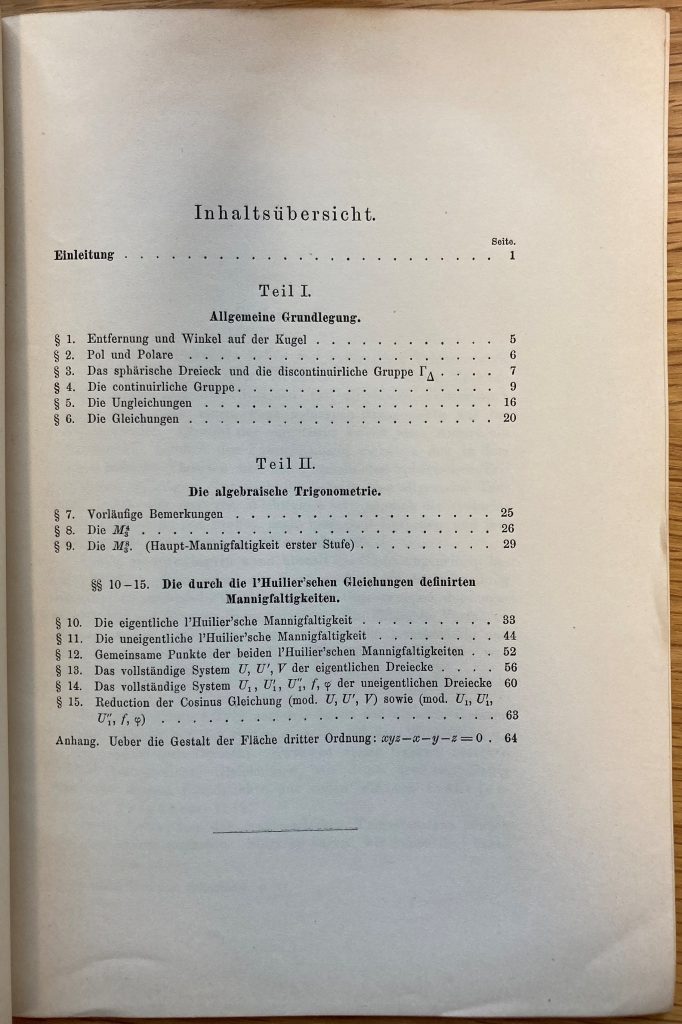

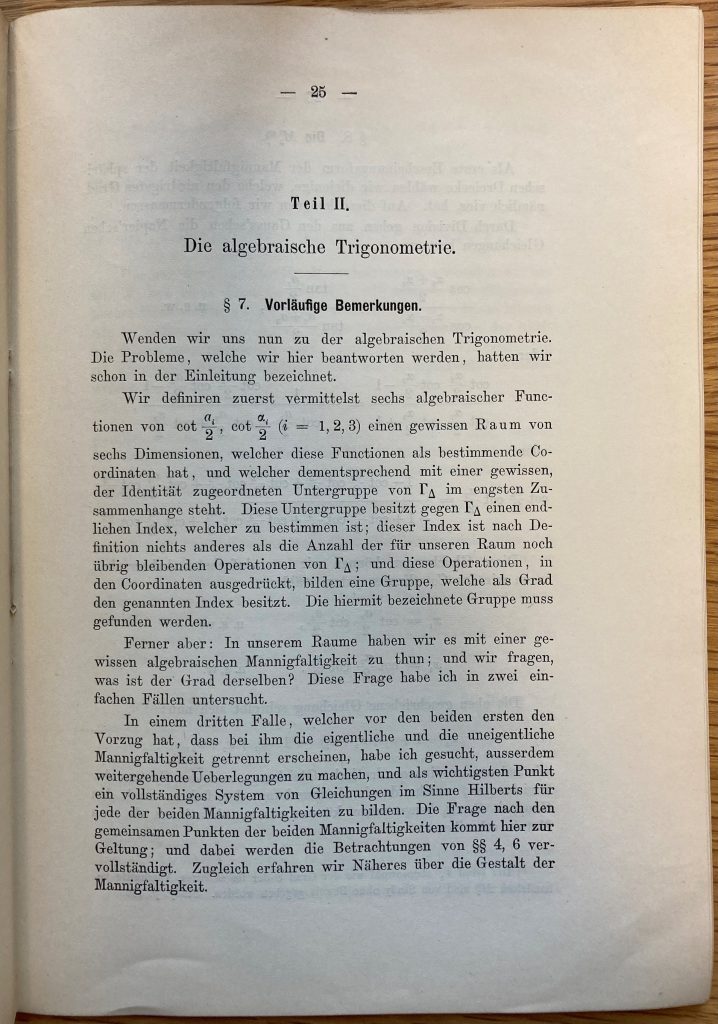

Grace Chisholm was born in 1868 and was schooled at home, before passing the entrance exams for Cambridge and matriculating at Girton College in 1889, where she remained for four years. She had wanted to study medicine but – this being frowned upon by her mother – chose mathematics. She excelled, and in 1893 passed her final examinations with the equivalent of a first-class degree, ranked between 23 and 24 relative to 112 men. She also took the exam for the Final Honours School in mathematics at Oxford in 1892 in which she out-performed all the Oxford students, becoming the first person to obtain a First class degree at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities in any subject (although they were not awarded formally due to the place of women in both institutions at the time). During her time at Cambridge she corresponded with George Darwin (son of Charles), and five letters from Grace are to be found in the University Library (MS DAR 251: 4388-92). Since women were not yet admitted to graduate study in the UK (Cambridge’s own PhD programme was not instituted until 1919), she moved to Göttingen (Germany), where she studied under Felix Klein (1849-1925), known for his work with group theory, complex analysis, non-Euclidean geometry, and the associations between geometry and group theory. Her PhD, the first in any subject to be awarded in Germany to a woman, was awarded in 1895, entitled (in translation) ‘Algebraic group-theoretical studies on spherical trigonometry’.

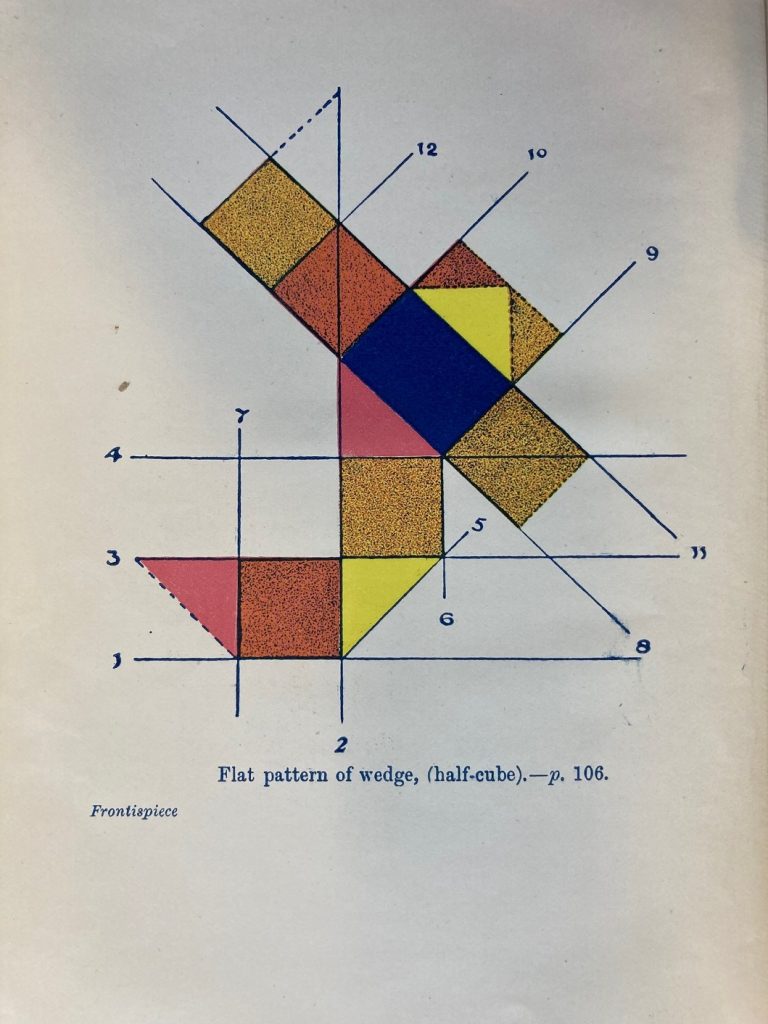

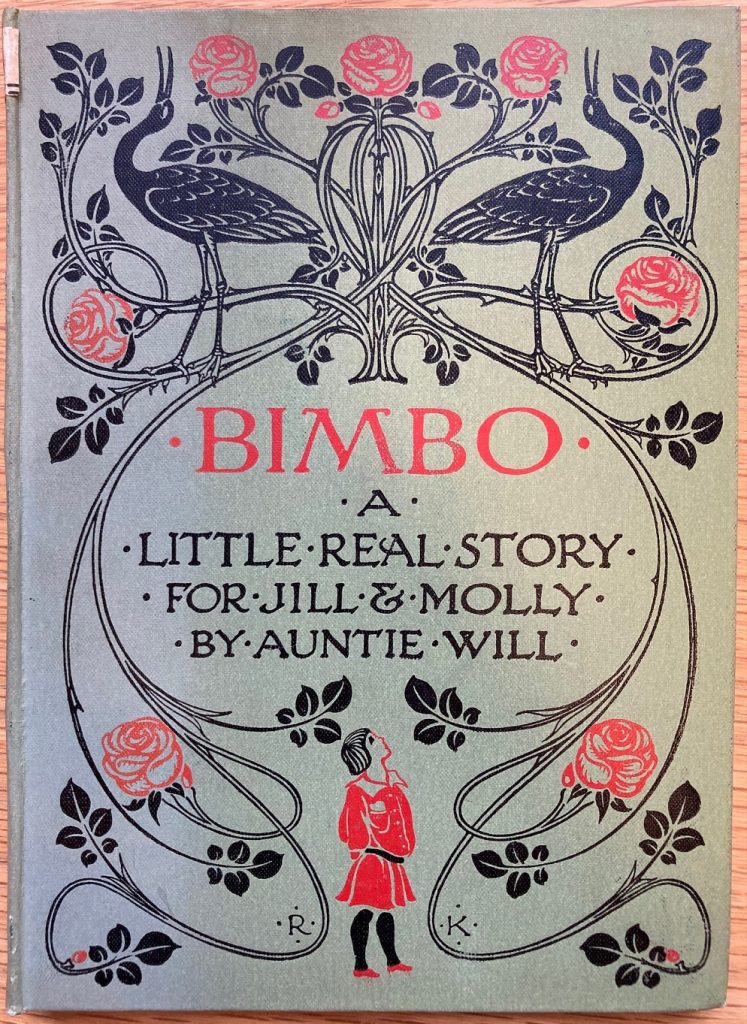

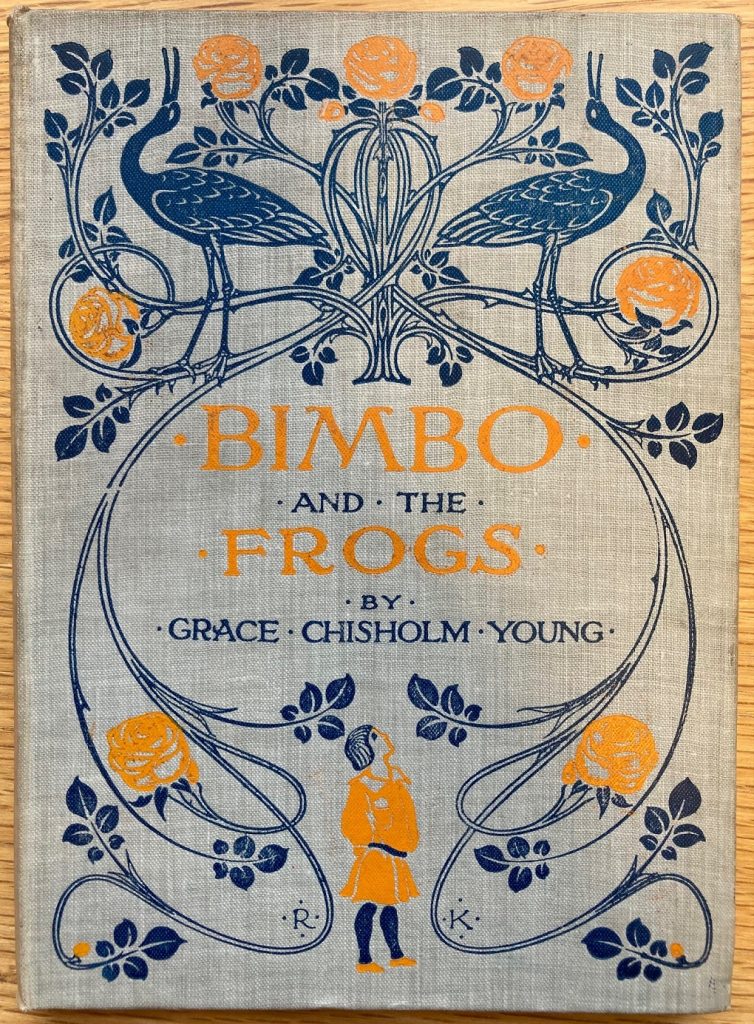

The year after the award of her PhD, Grace married the mathematician William Henry Young (1863-1942), and for the next couple of decades the pair lived between Göttingen, Turin, Geneva and India, both pursuing research. In 1913 William was the first to be appointed to the newly created Hardinge Professorship of Pure Mathematics in Calcutta University, which he held from 1913 to 1917. The pair co-authored several books, including The first book of geometry (1905) and The theory of sets of points (1906), though it is believed Grace often did the writing. The Library’s copy of the latter is inscribed by William to Frank Stanton Carey, Professor of Mathematics at Liverpool University (where William also held a post). In total, some 214 papers and four books were issued in their joint names. In her own name Grace published two books intended to impart scientific knowledge to children: Bimbo: A Little Real Story for Jill and Molly (1905), which explained where babies came from, and Bimbo and the Frogs: Another Real Story (1907), on cells. Both have rather wonderful art nouveau covers, decorated with flowers and birds…

Grace was awarded the Gamble Prize for Mathematics by Girton College in 1915 for an essay On infinite derivates and in 1944 the College recommended her for Honorary Fellowship, but she sadly died before it could be conferred. Her legacy lives on in her children and grandchildren: her daughter Rosalind Tanner (1900-92) took a Cambridge PhD in mathematics in 1929 and spent her professional life teaching at Imperial College London, and her grand-daughter Sylvia Wiegand (b. 1945) is a Professor at the University of Nebraska and was President of the Association for Women in Mathematics.

I think the translation “sparse trigonometry” should be “spherical trigonometry”.

Thanks for this. I must have copied it from another description without checking. I see actually that the German word ‘spharischen’ translates as ‘spherical’, which I have corrected it to. Liam Sims.

I had the honour of seeing The Theory of Sets of Points during Open Cambridge 2025 at the event ‘500 Years of Science in Print at the Whipple Library. Thanks to the detailed introduction provided by the librarians, I was deeply moved by Grace’s story. The book, filled with her annotations in multiple languages, became even more precious. My sincere thanks to everyone involved in preserving these rare books and promoting their educational value to the public. It is truly a privilege to experience such treasures in Cambridge, even without being a student of the University.

Thank you!