Childbirth and charms: two new online exhibitions

This guest post is by Summer Mainstone-Cotton and Aine Widdicombe, who are Masters students at the Universities of Bristol and Cambridge respectively.

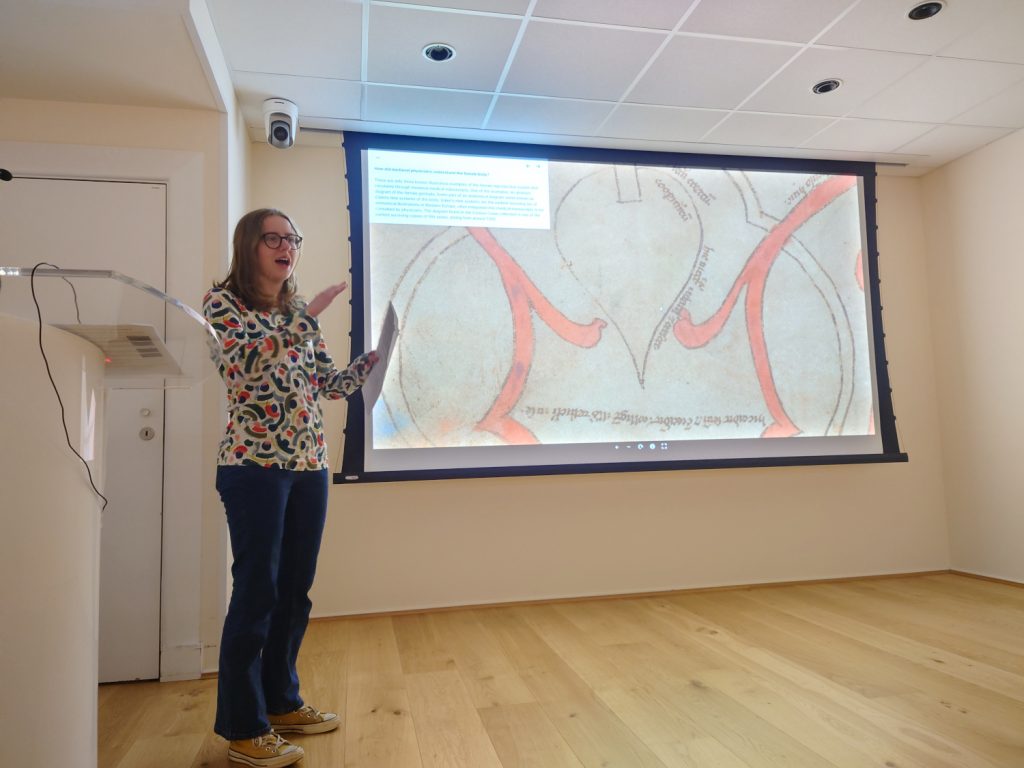

Earlier this year, Summer and Aine participated in a placement on the Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries project at Cambridge University Library. Their brief was to design an online exhibition of manuscripts, drawing on examples from the project, in order to share these materials with a broader audience. At the end of their placements, they presented their finished exhibitions to a gathering of project and UL staff.

Their online exhibitions are now online and available for everyone to view. They provide excellent introductions to a wide range of medieval medical manuscripts, their production, contents and use — and Summer and Aine have written the following by way of an introduction to their work.

To view Summer’s exhibition, click here: Childbirth within the medieval world

To view Aine’s exhibition, click here: Charms in medieval medical manuscripts

This is the second such placement organised in conjunction with the Curious Cures project. The results of the first were reported in the blog post Zodiac Men and Talking Books.

Summer Mainstone-Cotton

Curating the digital exhibition ‘Childbirth Within the Medieval World’ and working with the Curious Cures project at Cambridge University Library has been a fantastic opportunity, allowing me to delve into the rich topic of medieval reproductive health. I came to the Curious Cures Project as part of a placement unit for my Medieval Studies Master’s degree at the University of Bristol. My aim was to use digitised medical manuscripts to shed light on how medieval women experienced childbirth – a challenge, considering that these manuscripts were typically written by men.

Childbirth and women’s reproductive health seemed the perfect topic for this exhibition. It is a subject familiar and personal to everyone and thus provided an accessible entry point into the world of medieval medicine for a non-specialist audience. It is also central to my current research interests, since it forms the subject of my in-progress dissertation. Initially, my research focused on charms and prayers used by women during childbirth, but after exploring the manuscripts in the collection, I quickly realised the breadth of material on medieval childbirth that was available. This culminated in an exhibition that traverses the entire pregnancy cycle: from fertility and pregnancy, to birth, and finally to post-partum recovery.

There is a rich array of gynaecological and obstetric texts and advice within these medical manuscripts, sometimes in the most unexpected places. One particularly intriguing find was a remedy for strengthening a woman after childbirth, squeezed into a blank space at the end of a veterinary health manuscript that largely contains treatments for horses.

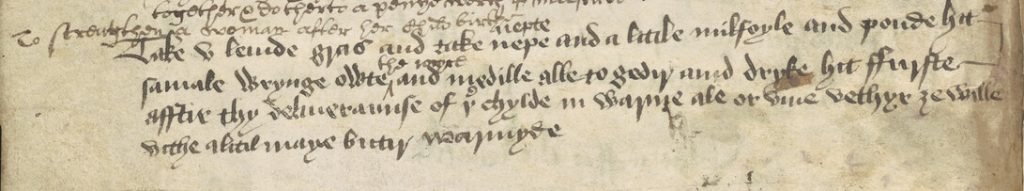

Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd.4.44, f. 35v

The recipe calls for a collection of herbs to be juiced and drunk ‘after the deliverance of the child in warm ale or wine, whichever you prefer, with a little butter, made in May, warmed’. What I particularly enjoyed about this project was stumbling upon such evocative details: the ingredients in this Middle English recipe would have readily available to gather in a garden or to forage, and it is easy to imagine the servants or family of a new mother preparing this remedy for her.

Cambridge, Gonville & Caius College, MS 190/223, f. 5v

(reproduced by permission of the Master and Fellows of Gonville & Caius College)

One of the few illustrated manuscripts within this exhibition contains a diagram of the womb. The manuscript in which it is found was made in the late 12th century, but the knowledge on which it is based is much older: it is part of a set of representations of ‘nine systems’ of the body, which were first described by Galen (b. 129, d. 216), a Greco-Roman physician. The diagram is a visually striking, abstract depiction of the womb, in which the uterus is outlined in red ink. Remarkably, it is based not on the anatomy of a human woman’s anatomy, but on that of a pig. This highlights the limitations of medieval medical knowledge of women’s bodies: they were not able to practice human dissection and so relied on animal anatomy to gain a rudimentary understanding of the uterus’s function. Although various texts in the Curious Cures collection seek to provide guidance and cures for women’s reproductive health, there were limits to medieval people’s understanding of the more intricate inner workings of the female body.

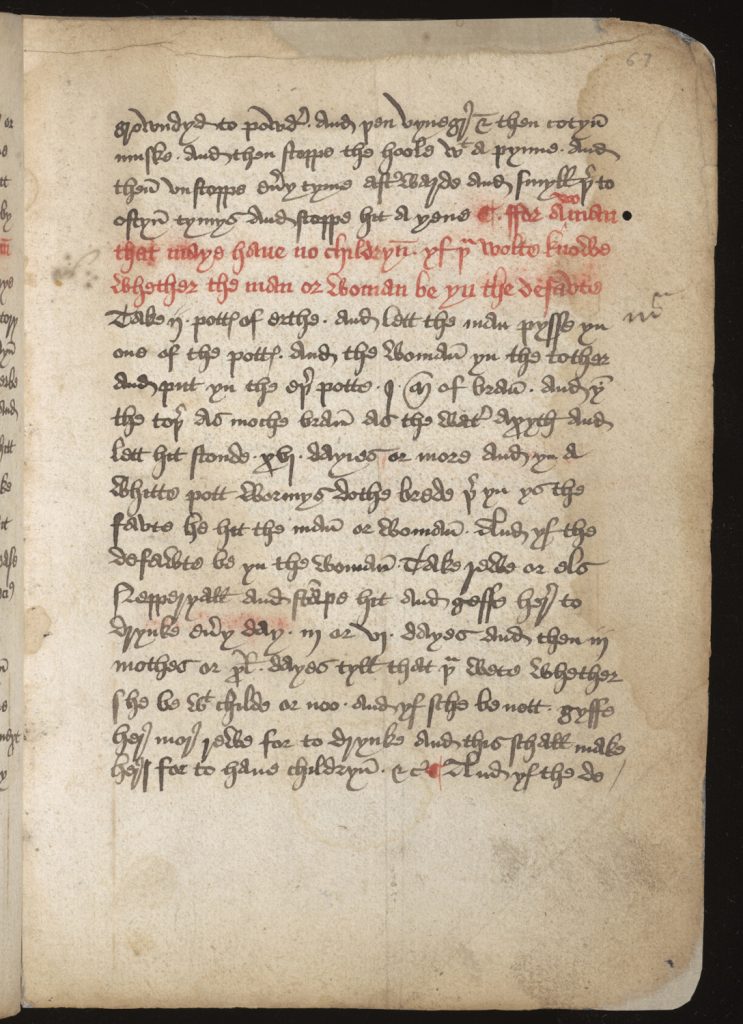

An exhibition audience is likely to have some preconceived ideas about medieval medicine, and to imagine all sorts of disgusting concoctions comprising seemingly random selections of ingredients, or a hit-and-miss trial-and-error approach based on superstition or unproven theories. There are indeed plenty of remedies or pieces of advice that seem very strange to the modern mind – and reproductive health is no exception. One such example seeks to determine the cause of a couple’s infertility: it instructs the man and the woman each to urinate into separate pots of earth, which are to be left for sixteen days. Whoever’s pot is found to have worms breeding in it after that time has elapsed, is the person responsible for their childlessness. Treatments tailored specifically for each partner were then offered. Behind these instructions, it is very easy to imagine medieval men and women who wished to conceive, not knowing the reason why they could not, and placing their faith in the only medicine and science available to them.

Cambridge, St John’s College, MS K.49, f. 67r

(reproduced by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College)

The exhibition I have created is filled with such fascinating and sometimes poignant examples. The texts are written in a variety of languages unfamiliar to modern audiences: Latin, Middle English and Old French. By providing transcriptions and translations alongside the images, I invite viewers to engage and attempt to read these handwritten texts from centuries ago. What resonated with me when reading them was the intimacy I felt with medieval women who were trying to conceive, preparing to give birth, or trying to care for a newborn child, and relying on the knowledge preserved within these books. I hope that the exhibition will enable a wider audience to experience that same connection, by making this fascinating corner of medieval medical history engaging and accessible.

Aine Widdicombe

Have you ever wondered how magic and religion, two seemingly opposing forces, were able to coexist in the medieval period? My exhibition, ‘Charms in Medieval Medical Manuscripts’, shows how the two were often juxtaposed and even combined in the context of medical treatments by exploring a number of examples from manuscripts that have been digitised and catalogued as part of the Curious Cures project.

What is a charm?

Charms were used to influence events through the speaking of words and performing of actions. Their purposes in the medieval period were very varied, including giving protection against theft or manslaughter, or helping someone to find buried treasure. Some charms were used to treat and cure illness and they are frequently found among collections of medical recipes. Charms often included religious language, ciphers, ritual performance, instructions on how to create and use powerful ‘apotropaic’ or protective objects and amulets, and statements that declared their efficacy to a reader. My exhibition explores each of these in turn – and as a taster, we will delve into three of them here.

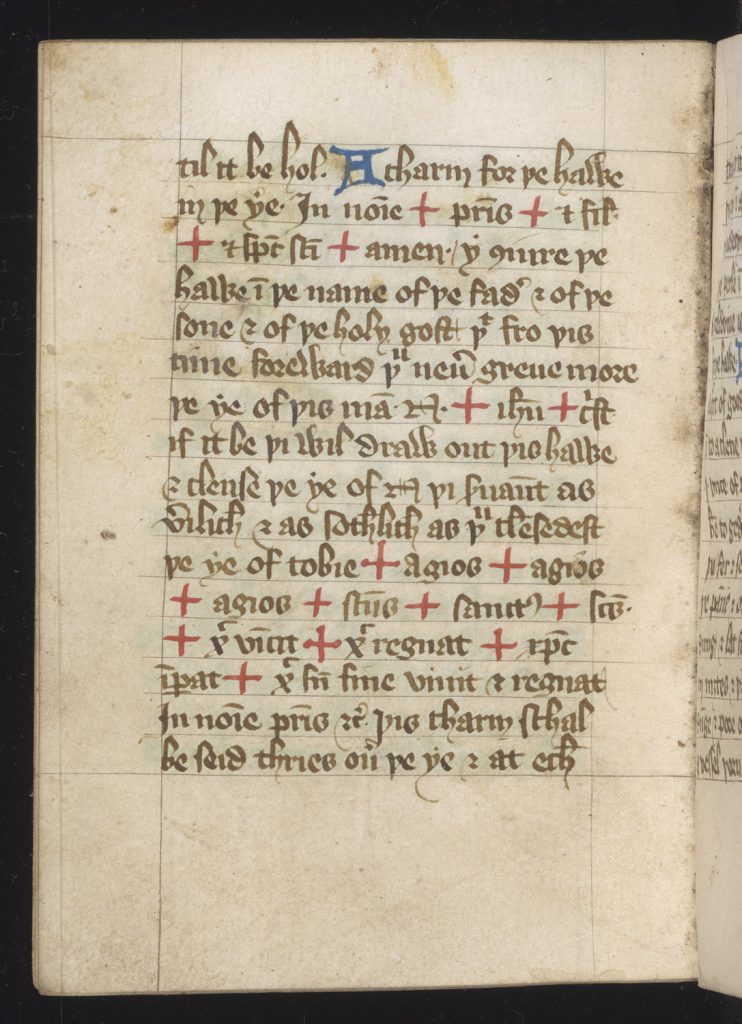

Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 9308, f. 22v

Ritual performance

Charms could include aspects of ritual performance, where physical movements or signs were made by the person who was enacting the charm. An example of this was making the sign of the Cross. In the example shown here, red crosses are dotted among the text: these are prompts to the reader to make the sign of the Cross several times and at certain points as they recited the words of the charm. These crosses highlight the overlap between ritual performance in medical charms and religious rites: the same technique of interspersing crosses among a text is found in liturgical books, which likewise directed the priest when to make the sign of the Cross, for example during the performance of the Mass. The user of a charm was not necessarily a priest, however, but the recurrence of such crosses in charms shows that medical practitioners thought that the religious power of the sign and of making it could be harnessed in a magical way to help heal a patient.

Apotropaic objects

A wide range of apotropaic objects are referenced in healing charms: they could be specially made amulets, rings, or simply everyday objects that had been imbued with a magical power by the performance of a charm. One example in the exhibition is a magical hazel branch that was used to cure bleeding. It is accompanied by a small diagram that illustrates how the hazel rod was to be split in two, through which gap the sufferer was to place his or her head.

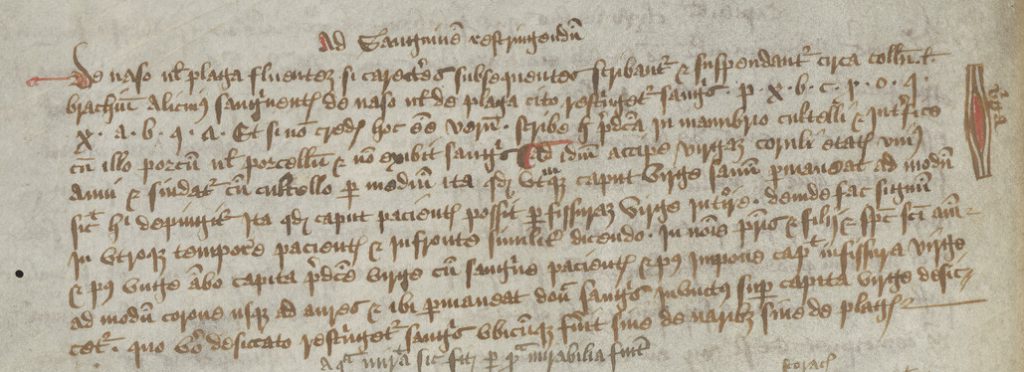

Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd.3.52, f. 250v

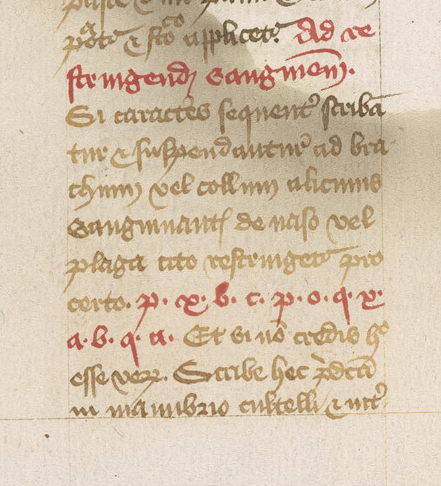

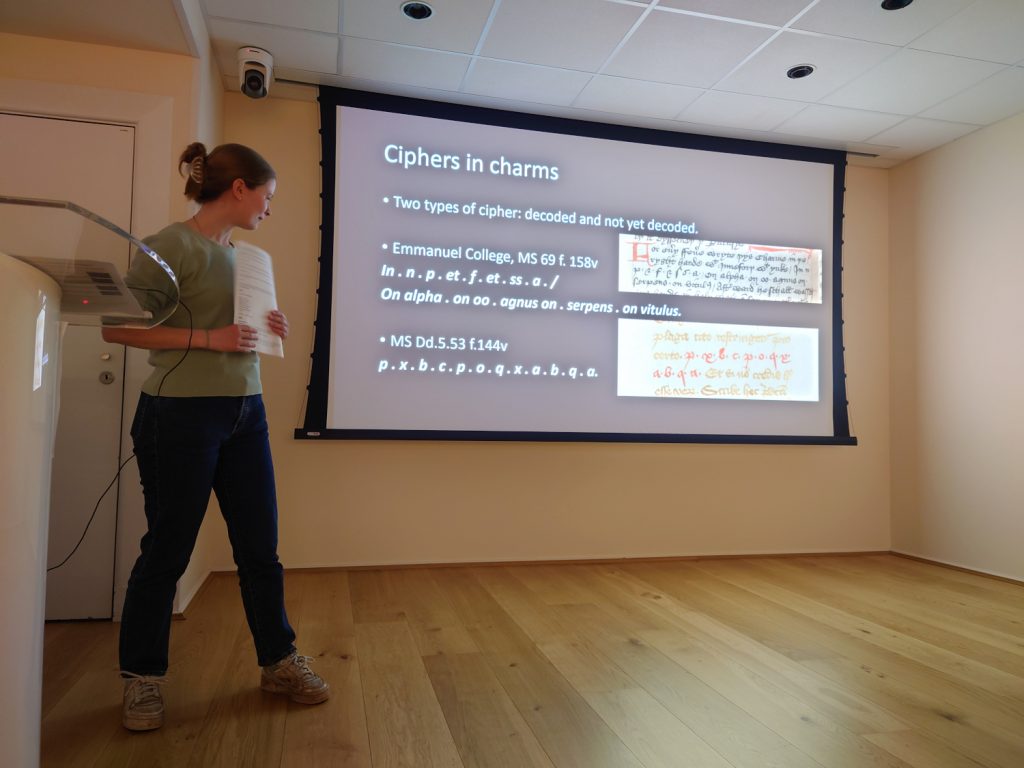

Ciphers

As well as making objects, charms also required their users to say words out loud – words that were again often drawn from religious ritual or scripture. In some instances, these words are shortened in the charm text to their first letters only. These are often described as ciphers and they present a fascinating puzzle to the modern reader. Some can be easily decoded, whereas others remain a mystery. Some charms to staunch blood include the following cipher or variations on it, for example:

p . x . b . c . p . o . q . x . a . b . q . a.

These are written in red ink in the manuscript (see illustration).

This is likely a Latin phrase or prayer: ‘x’, in place of the Greek letter ‘chi’ (‘χ’), is often used in abbreviations for ‘Christus’. In some versions of the cipher, the third letter is ‘v’ rather than ‘b’: in the context of a charm against bleeding, this suggests that it might relate to St Veronica / St Berenice. The story is that she suffered from haemorrhaging for twelve years, but was healed when she reached out and touched Christ’s cloak. But what might the remaining letters mean? Do you have any ideas?

It is unclear why charms sometimes used such ciphers: were the words abbreviated simply for the convenience of the scribe who copied them, and was their reader expected to know their meaning? Or were they deliberately intended to conceal this, so that only those ‘in the know’ could understand the charm in full?

Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd.5.53, f. 114v

Conclusion

Charms vividly illustrate that a fluid and permeable boundary existed between official religion and popular magic. Ritual gesture and performance, religious words and phrases, and the power of objects were each deployed in the hope of transforming a person’s health. Emulating the acts and words of priests, imitating liturgical rites, and using religious words or phrases in Latin, all show how medieval people sought to harness the power and legitimacy of the Church and of religion in order to heal and to cure.

What does one of the illustrated manuscripts within the exhibition contain?

The illuminated manuscript which shows a diagram of the womb (Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College MS 190/223) has been digitised in full. You can see all its pages here: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-GONVILLE-AND-CAIUS-00190-00223/1

The diagram shown is one of a series at the beginning of the manuscript.