‘A thing useful against evils’ – An Anglo-Saxon gospel book from Northumbria

For early medieval Christian communities, a gospel book was a treasured possession and, according to an Anglo-Saxon riddle, ‘a thing useful against evils’. The most outstanding example of an Anglo-Saxon gospel book is undoubtedly the Lindisfarne Gospels but this was a deluxe production. A much more typical example of the gospel books produced in eighth-century Northumbria is CUL MS Kk.1.24 which has just been digitised and is available in the Cambridge Digital Library. Its pages reveal many of the ways this precious book was used over the centuries.

First and foremost it was a book to be used for reading the word of God. It is written in a beautifully clear half-uncial script. The surviving decoration is minimal and rather functional – initials of different sizes are surrounded with red dots to indicate textual divisions, as also seen in other contemporary gospel books. Only the second half of the book survives, that is, the gospels of Luke and John, and the beginnings of both gospels are missing. Although nothing like as lavish as the Lindisfarne Gospels, each gospel was probably preceded by a full-page frontispiece depicting the evangelist and a large opening initial.

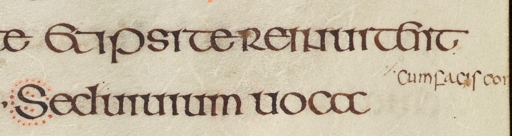

The text was read carefully. Here at Luke 14:13, a reader has added the missing words ‘cum facis con-‘ in the margin. The tiny signes de renvoi ·/. can just be seen beside them and before ‘uiuium’ in the text, indicating what was to be added and where.

Elsewhere rubrics have been added in the margins indicating the start of gospel passages to be read on a particular feast day, suggesting that the book was being used as part of the liturgy. Here a passage from Luke’s gospel is marked for the feast of the Nativity of Mary.

At the top of one page a verse and response with musical notation have been added, also indicative of liturgical use.

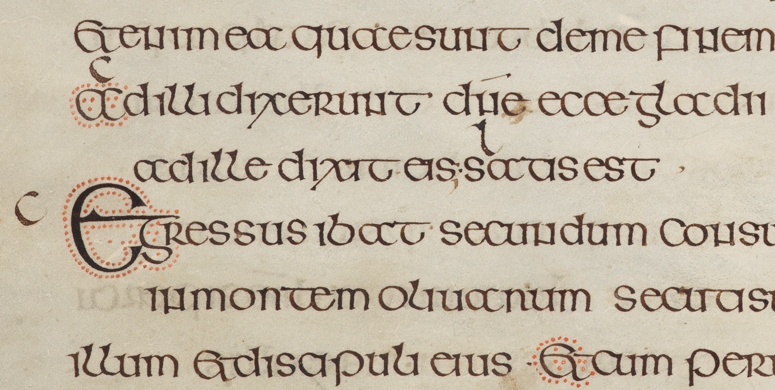

Perhaps the most intriguing addition to the biblical text is the letters ‘l’ and ‘c’ which have been inserted at various points towards the end of each gospel, as in the image at the top of this post from Luke’s gospel. These represent cues to two speakers, ‘Lector’ (narrator) and ‘Christus’, who would have performed readings of the Passion narratives, an important part of the liturgy around Easter. These cues are often found in early medieval bibles but, as Patrick McGurk points out, just because they were copied in does not necessarily mean that the book was actually used for this purpose. In this manuscript, the cues are the ‘wrong’ way round: Christ’s words ‘satis est’ are marked ‘l’ and then the narrator’s next line, ‘Egressus ibat…’ is marked with a ‘c’, perhaps indicating where the speaker should stop rather than start.

Judging from the script and a surviving scrap of decoration, many of the additions to MS Kk.1.24 seem to have been made in the tenth century and we know that by this stage the book was no longer in Northumbria but at Ely Abbey. In addition to reading and possibly performing from the book, the monks used its blank spaces to record information relating to their estates. John’s gospel ended with only a few lines on a page and further down the page, a list of serfs belonging to the abbey’s estate at Hatfield in Hertfordshire was added. It is not unusual to find charters recording the transfer of land or records of manumissions in early medieval gospel books. It made sense to record information important to the community within the covers of a volume that was venerated – and that would be one of the first items to be rescued in case of fire or other disaster.

Different attitudes to the book prevailed in the sixteenth century and antiquaries interested in the Old English text removed this final page. Two fragments of it are now found in different collections in the British Library, along with a fragment of another page recording a land grant in Old English.

Despite the loss of many of its pages in different circumstances over the centuries, MS Kk.1.24 with its functional design and abundant evidence of its long working life remains an important example of a under-appreciated class of manuscript. As Richard Gameson points out, although every monastery and minster in Anglo-Saxon England would have needed at least one workaday copy of the gospels for daily use, books like MS Kk.1.24 ‘are now scarcer, paradoxically, than their higher-grade counterparts’. There’s a rare opportunity to see MS Kk.1.24 alongside the Lindisfarne Gospels and several other Anglo-Saxon gospel books in the current Lindisfarne Gospels exhibition at Durham which is on until 30 September 2013.

Bibliography

Richard Gameson, From Holy Island to Durham: the context and meanings of the Lindisfarne Gospels (Third Millennium Publishing, 2013).

This is the catalogue of the Lindisfarne Gospels exhibition. The title of this blogpost is taken from Gameson’s partial translation of the Exeter Book riddle on p. 133.

Patrick McGurk, ‘The oldest manuscripts of the Latin Bible’, in The early medieval Bible: its production, decoration and use, ed. by Richard Gameson (CUP, 1994), pp. 1-23.

Pingback: Absence as Evidence: Recovering the Losses in an Eighth-century Gospel Book – Cambridge University Library Special Collections