Rupert Brooke: 100 years on

A century ago today – on 23rd April 1915 – died Rupert Brooke, lauded in his lifetime as one of the country’s finest poets. This post explores his short life and what remains of his personal library among our collections. His poetry – much of it concerned with the effects of the First World War – has come to represent the loss of a generation, and The Soldier (read in the pulpit by the Dean of St Paul’s on Easter Day 1915) is one of the most famous war poems ever written, its first lines forever stamped upon the minds of successive generations: If I should die, think only this of me: / That there’s some corner of a foreign field / That is forever England. There shall be / In that rich earth a richer dust concealed. Brooke was born in Rugby (Warwickshire) in August 1887 and attended the town’s famous school (founded in 1567), where he contributed to the magazine The Phoenix. By the age of 17 he had befriended the poet St John Lucas, a devotee of Oscar Wilde. Brooke entered King’s College Cambridge in October 1906 and spent the next three years cultivating his intellectual and artistic persona. Moving in the circles of the (in)famous Bloomsbury Group, he befriended Lytton and James Strachey, Geoffrey and Maynard Keynes and Virginia Woolf, and was elected to the deeply secretive Apostles, a discussion society of no more than twelve members (hence the name). W. B. Yeats called him “the handsomest young man in England”. During 1911 he travelled in Europe and published his first volume of poetry, but later that year went through something of an emotional crisis when his relationship with Ka Cox fell apart, the fault – he believed – of James Strachey, which led to the cutting of all ties with Bloomsbury.

By 1912 things began to look up. Brooke was by now patronised by Edward ‘Eddie’ Marsh, who introduced him to a host of eminent individuals, including Winston Churchill (to whom Marsh was Secretary), Henry James and George Bernard Shaw. In 1913 he was awarded a fellowship at King’s, based on his dissertation on the English playwright John Webster, but a lengthy period abroad (notably spending much time in Tahiti) delayed his return to Cambridge and the First World War finally intervened. He was commissioned into the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as a Sub-Lieutenant and went that October to Antwerp, ravaged by the Germans. On 28 February 1915 he set off with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and his death came two months later when he developed sepsis from an infected mosquito bite. Before the end came Brooke had already begun to shape his posthumous persona; his friend Dudley Ward was directed to destroy all letters from those women with whom Brooke had been involved romantically. “Indeed, why keep anything,” Brooke wrote. “Well,” he continued, “I might turn out to be eminent and biographable. If so, let them know the poor truths…”. Brooke’s premature death during the First World War gave him a mythical, almost god-like status, and the fact that it came on St George’s Day (not to mention on the anniversary of Shakespeare’s death) added to the sense of the loss of a great national figure. Brooke was buried immediately on the Greek island of Skyros and the news reached King’s College on April 25th. On the following day Theo Bartholomew, on the staff at the University Library, wrote in his diary that it was “a loss to English poetry and still more in my opinion to English [literary] criticism”.

Beardsley’s illustration for Wilde’s Salome, in Brooke’s copy of Robert Ross’ “Aubrey Beardsley” (1909), inscribed by Brooke to Geoffrey Keynes. Keynes.J.7.17

Tributes poured in, and Winston Churchill (at that time First Lord of the Admiralty) penned an obituary for The Times, writing that Brooke’s life had “closed at the moment when it seemed to have reached its springtime”, continuing that he was “Joyous, fearless, versatile, deeply instructed, with classic symmetry of mind and body, ruled by high undoubting purpose…all that one would wish England’s noblest sons to be in the days when no sacrifice but the most precious is acceptable.”

Woodcut by Phyllis Gardner of Brooke’s grave, in Casson’s “Rupert Brooke and Skyros” (Keynes.J.5.25)

Although the quality of Brooke’s poetry spoke for itself and quickly inspired public admiration, the tributes which marked his death presented to the world an infallible figure very far from the real Brooke. He may have been a poetic genius, but his friends knew that he could also be – like many of us – selfish, childish and, at times, cruel; in the words of one more recent biographer, “a human being with a full flush of faults and flaws.”

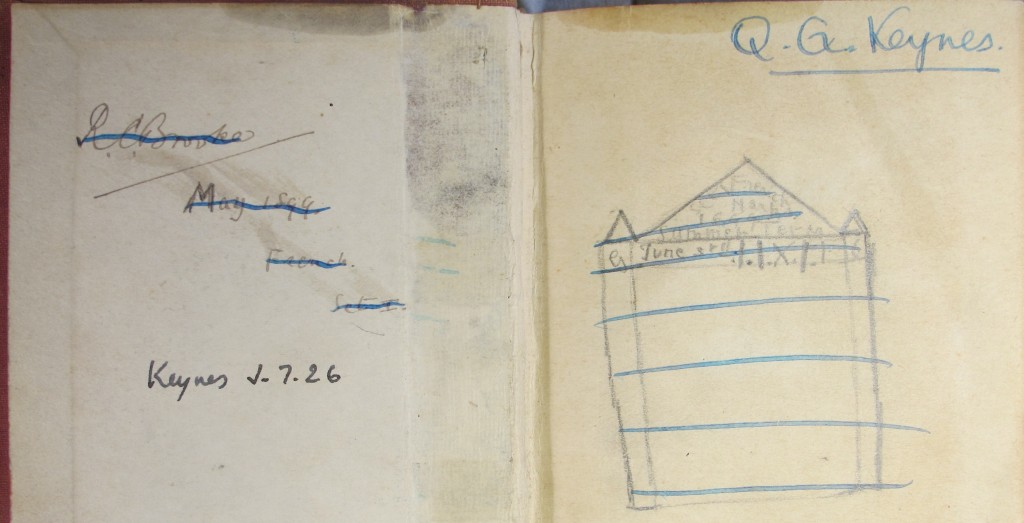

Bartholomew captured the mood in Cambridge when he wrote in diary some two months later that “People are losing their heads about him I think,” and two years later Virginia Woolf recorded in her diary that Brooke was “jealous, moody [and] ill-balanced”. But his reputation as a great war poet lives on, partly thanks to his friend Sir Geoffrey Keynes; surgeon, book-collector and – as guardian of Brooke’s papers for many decades of his own long life (having over-ruled Brooke’s choice of Eddie Marsh in favour of himself, with the help of Brooke’s formidable mother) – keeper of his flame for much of the twentieth century. In addition to fending off prospective (and in his opinion) unsuitable biographers and publishing a very incomplete edition of Brooke’s letters (devoid, among other things, of any reference to Brooke’s experimentations with homosexuality), Keynes preserved a portion of his friend’s personal library among his own books. The Keynes Collection, which came to the University Library after Keynes’ death in 1982, is one of the jewels in the crown of the Library’s collections, containing many early English works, fine bindings and significant provenances among its 8000 volumes. Keynes published bibliographies of many authors, amassing complete collections of their works, including John Donne, William Blake, Jane Austen, Siegfried Sassoon (with whom he was also friends) and Brooke himself. Brooke had given Keynes books in his own lifetime and at his death, more passed to him; some forty volumes now in Keynes’ collection formerly belonged to Brooke. Among them are a presentation copy of Edmund Gosse’s 1912 “Life of Swinburne”, one of just fifty copies printed (Keynes.J.7.12), an 1897 pocket English/French dictionary (Keynes.J.7.26) used by an eleven-year-old Brooke at school (and later given by Geoffrey Keynes to his son Quentin), and a miniature 1903 edition of the comedies of Shakespeare (Keynes.J.7.27) inscribed by Brooke in February 1915 just as he set off on what would be his final voyage.

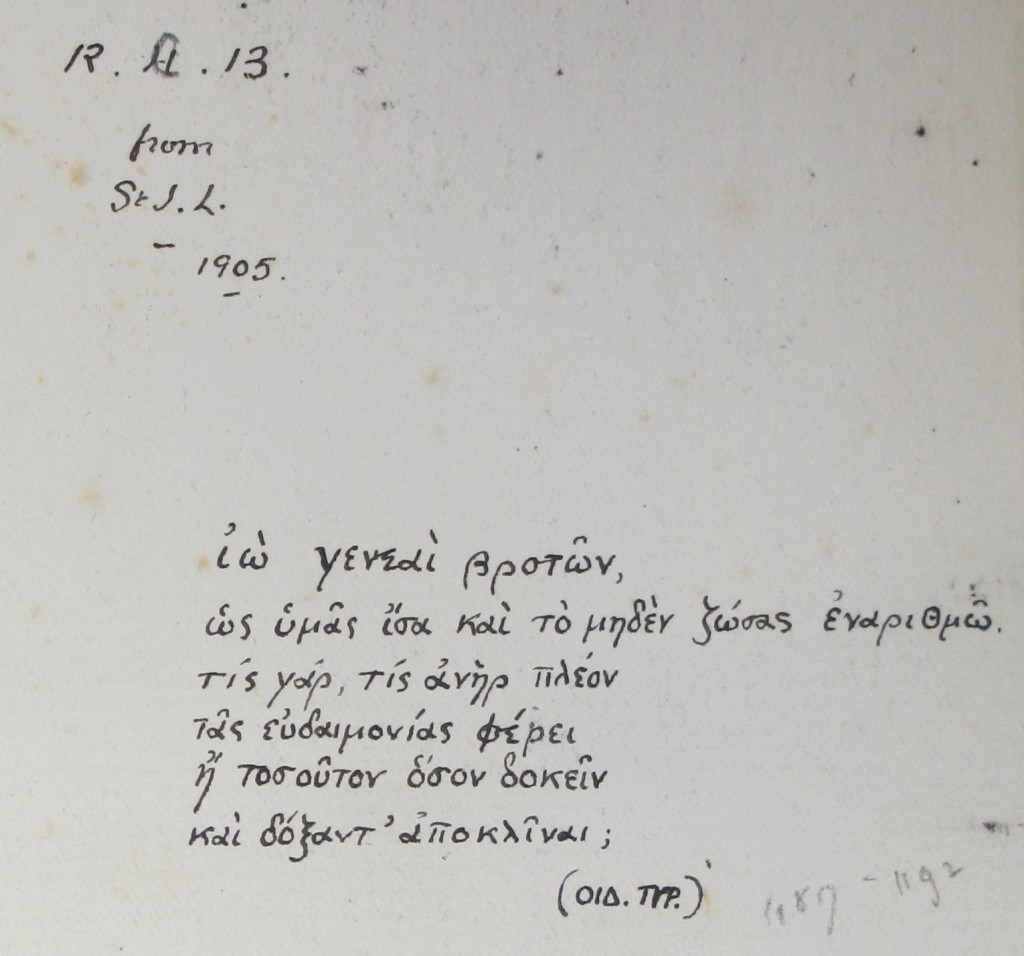

Gift inscription from St John Lucas, with a quotation in Greek from Sophocles’ Oedipus the King (lines 1187-1192), in Brooke’s copy of Wilde’s De Profundis (1905), Keynes.J.7.11. Lucas befriended the 17-year-old Brooke in 1905 and became an early mentor. The gift of this volume may be the result of a letter in which Brooke asked Lucas to send him “the three great decadent writers (Oscar Wilde, St John Lucas, and Rupert Brooke)”.

These books, with their personal inscriptions and annotations, along with Brooke’s personal papers held in the Archives of King’s College, make Cambridge the centre of Brooke studies. King’s has today made the exciting announcement of the acquisition of the most significant collection of Brooke manuscripts remaining in private hands – the John Schroder collection – and plans to exhibit some of its contents in the college chapel later in the year. King’s has also set up a website, using Brooke’s papers as a case study, to introduce GCSE and A-Level students to the use of archive collections. These precious remnants of Brooke’s short time on this earth give us a privileged window onto the personal life of a man who has – in death – become a cornerstone of English literary culture.

Pingback: Rupert Brooke: 100 years on | Cambridge University Library Special Collections

Pingback: Digitising and opening up the history of Cambridge (the town) – Lost Cambridge