The Early Catalogues of the University Library: A New Subject Guide

Perhaps the most common enquiry regarding our medieval manuscripts concerns their provenance: in particular, when they might have arrived at the University Library. Our manuscripts contain all sorts of evidence bearing on their medieval movements: institutional or personal ownership inscriptions, ‘cautio’ notes from deposit in a loan chest, coats of arms, revealing marginalia or associated contents, a significant combination of local saints in a calendar or litany, and so forth. However, they are less revealing of their post-medieval ownership and recourse to other records is often necessary.

Help is now at hand: the first of a series of medieval manuscripts subject guides has just been published on the University Library website. ‘Early catalogues of manuscripts, up to 1600’ deals with the fifteen handwritten or printed lists of books that were either at or given to the University Library in its earliest years. Thanks to the scholarship of Peter Clarke, Elisabeth Leedham-Green, David McKitterick, J.C.T. Oates, H.L. Pink, Henry Bradshaw and others, these records have now all been edited: where possible, the texts they describe have been identified as well as any of the surviving manuscripts. Details of all these publications are provided in the guide, with UL shelfmarks. In the name of comprehensiveness, references and links are also given to earlier editions – many of which have been digitised and are now online – however reference to the most up-to-date works is strongly recommended.

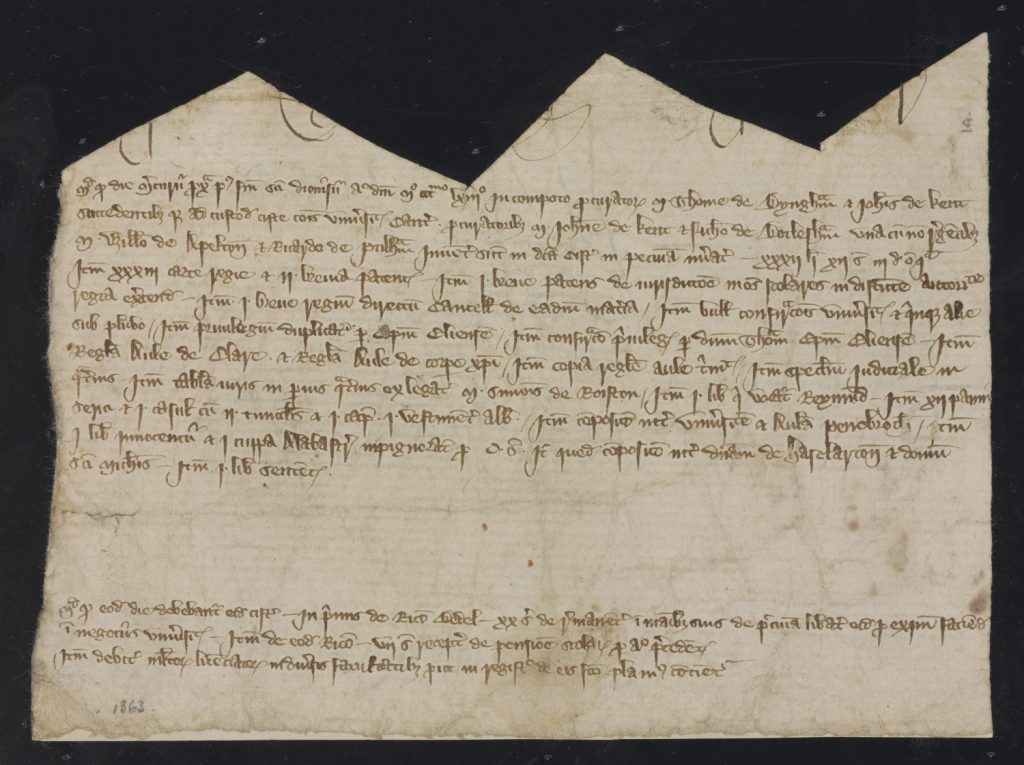

The first list of books in fact pre-dates the formation of the Library, being an inventory of books kept in the University’s common chest in 1363 (likely similar to the chest displayed in the Entrance Hall as part of the Library’s 600th anniversary exhibition, Lines of Thought). None of the four works of canon law or the theological text listed there is known to survive. The copy of Raymond of Pennafort’s Summa de casibus poenitentiae may be the same as that listed in the 1473 register as being kept in the fourth lectern on the south side of the library room – but without further corroboratory evidence, a definitive identification is not possible.

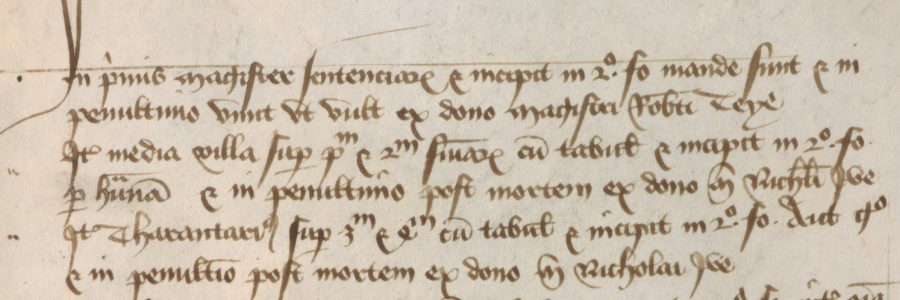

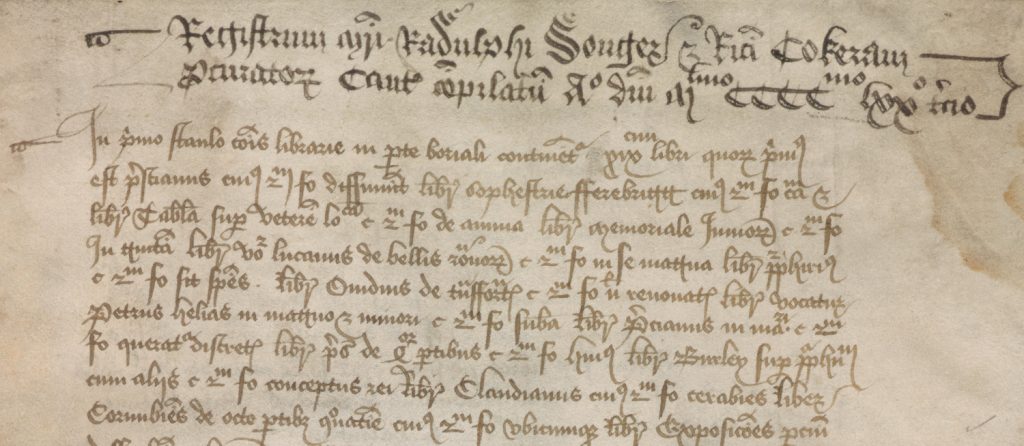

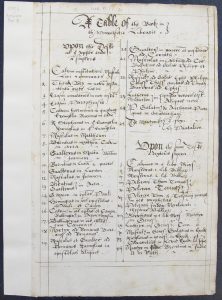

Many of these records are drawn from the University Archives, which are also kept at the University Library. While we might now use these lists as ‘catalogues’, their original function was not necessarily to help in the identification or location of books by readers. The list compiled between c. 1424 and c. 1440, and entitled ‘Registrum librorum per varios benefactores comuni librarie universitatis Cantebrigiensis collatus’, is concerned at least in part with the commemoration of those individuals who had given books to the Library. The first compiler of the list arranged the books by subject, leaving large gaps at the end of each section in anticipation of the arrival of further gifts; six other hands have subsequently made insertions in these spaces. Similarly, the 1473 register was drawn up by two University Proctors, Ralph Songer and Richard Cokeram, likely in preparation for the appointment of the chaplain-librarian, John Otteley, whose responsibility the books were to become.

A little over a century later, a series of draft lists were made under the supervision of Matthew Stokys, Registrary 1558-91, and later copied out neatly by John Frickley, notary public. What the 1473 and 1583 lists have in common is that they sit side-by-side with inventories of other objects: the silver seal, cash and muniments in the University Chest in 1420, or vestments and other ornaments in the ‘new chapel’ c. 1424; and keys, brass weights and measures, furniture, cushions of various kinds, University records and books of statutes and privileges, and even the glazing in the windows of various buildings, in the list made in 1583. Clearly, then, some of these records arose from general administrative activity concerned with the University’s valuable property and movable goods – of which books were nonetheless an integral part – rather than out of a concern to make the Library’s contents accessible to readers per se.

Other lists exhibit different priorities. 1574 saw the issue of two printed lists of manuscripts and printed books belonging to the University Library. One of these is sometimes found appended to De antiquitate Britannicae ecclesiae & priuilegis ecclesiae Cantuariensis, an antiquarian study composed by Matthew Parker (1504-1575), archbishop of Canterbury. Besides printed books, it lists some twenty-five manuscripts that Parker had agreed to donate to the University Library, where they are still easily spotted among the collection (the rest of Parker’s library books went to Corpus Christi College, where they remain to this day).

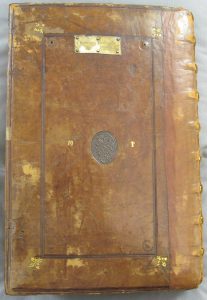

Rear board of Dd.2.5, showing horn label, drill-holes for bosses (now gone) and Parker’s initials stamped in gold

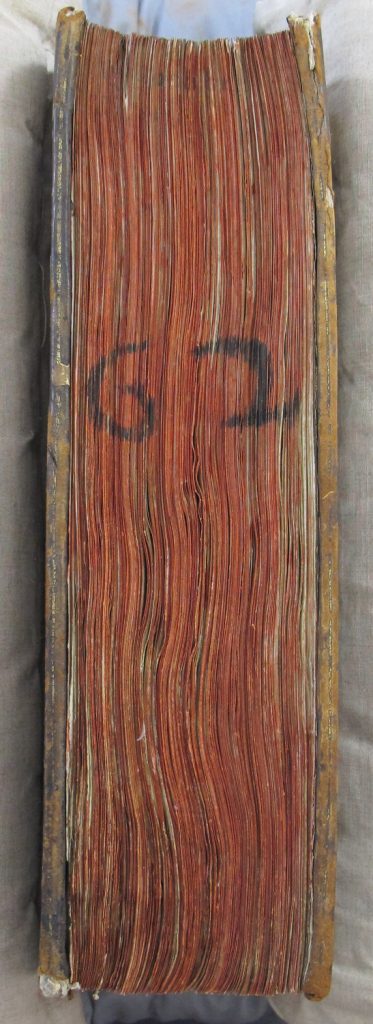

They are usually bound in wooden boards covered in brown leather, with simple blind-tooled decoration, at the corners of which are small drill-holes, indicating the presence once of metal bosses; these were designed to protect the binding, and also perhaps the small horn-covered labels found on the rear board, which name the text or texts a book contains. (Where the book has been rebound, the former pastedowns often bear witness to the same arrangements). This set of manuscripts also usually contain an inscription by Parker or evidence of his reading, with annotations in his characteristic orange crayon. It is these books that are subsequently denoted in the 1583 catalogue as being ‘locked up in the Cupborde’ that was situated immediately to the left of the door at the southern end of the Library when it was housed in the Old Schools. The presence of tell-tale drill holes at the foot of the binding of these Parker manuscripts also informs us that they were chained within the cupboard. The 1574 list therefore made the size and character of Parker’s gift public knowledge, and provided a permanent record of his generosity that subsequently informed the arrangement of the books in the Library.

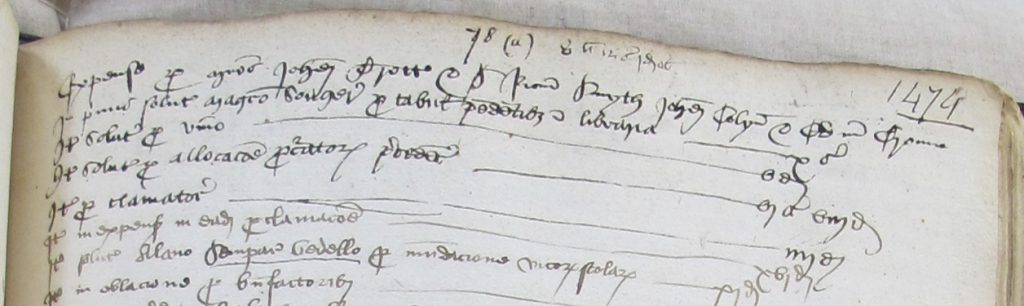

Nevertheless, a desire to make the location of books or the contents of the shelves known to readers was apparently felt in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, if only fitfully. According to University accounts for 1474/75, in addition to his work compiling the register of books earlier in the year, Ralph Songer was also paid the sum of ten shillings, ‘pro tabulis pendentibus in libraria’ (‘for the hanging tables in the library’): perhaps shelf-lists copied from the register and hung in the library for the use of readers.

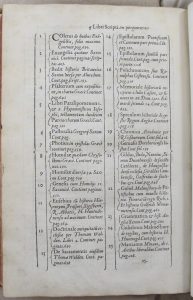

The first comprehensive printed catalogue of manuscripts at the University Library was produced in 1600. The list is one part of a survey of manuscripts collections across Oxford and Cambridge, the Ecloga Oxonio-Cantabrigiensis, conducted by Thomas James (1572/73-1629), who had been chosen the year before by Thomas Bodley to be the Librarian of his newly refounded, eponymous library in Oxford. The large numbers inked onto the fore-edge of University Library manuscripts correspond to the running numbers James assigned them in his list; they also indicate that books were stored with their fore-edges outwards and spines inwards (opposite to present custom), and perhaps that the Ecloga came to serve as an elementary finding aid.

These registers, inventories, catalogues and book-lists provide a window into the administration of the University Library’s earliest collections and their successive rearrangements. They also illustrate with particular clarity the period during which developed a collection of books, held for common use by scholars at the University, arranged in a particular way, in a designated room, and perhaps with finding aids – that is, a recognisable ancestor of the present-day University Library.

This is the first in a series of blog posts about the early catalogues of the University Library. The other two are available at the following links.

2. ‘Comings and Goings: The Movement of Manuscripts at the University Library before 1600’

3. ‘The Fluctuating Fortunes of the University Library during the 15th and 16th Centuries’

Pingback: Comings and Goings: The Movement of Manuscripts at the University Library before 1600 – Cambridge University Library Special Collections

Pingback: The Fluctuating Fortunes of the University Library during the 15th and 16th Centuries – Cambridge University Library Special Collections