The Fluctuating Fortunes of the University Library during the 15th and 16th Centuries

While elucidating finer points of library administration and the placing of manuscripts on the shelves, the early catalogues of the University Library additionally bear witness to the expansion and contraction of its stock, the influence of external events upon the Library’s fortunes, and the changing character of the medieval manuscripts collections.

The catalogues illustrate the transition from the simple storage of books alongside other valuables in a chest (probably not dissimilar to that shown here), to their more sophisticated arrangement on shelves in a room that would be recognisable as a library even today – and the concomitant growth of the collection that this both accommodated and facilitated. In simple numerical terms, we see the number of books held in common for the use of scholars increase from 123 by c. 1440, nearly tripling in size to 330 within less than a quarter of a century; J.C.T. Oates estimated a further doubling to around 600 volumes by c. 1530. Dramatic losses followed: by the time an inventory of the collection was prepared for the visitation by the Marian commissioners in 1556-57, after the abandonment of the Common Library in the mid-1540s, the collection was half the size it had been in 1473, with merely 163 volumes recorded. However, as the previous blog post illustrated, the movements of individual manuscripts reveals a more complex picture: some books irretrievably lost, yes – but others that disappeared only to reappear once more.

The list compiled in 1574 by John Caius, though usually overlooked, is valuable for what it tells us not only about the losses the Library sustained over these years but also for providing, at a glance, an overview of the kinds of books the Library contained. Unlike the other lists, it gives the books not by desk or stall, but by subject. We first encounter Grammar, Dialectic and Philosophy, Rhetoric and History, Arithmetic and Geometry and Astronomy, Cosmography and Music: groupings that correspond almost precisely to the trivium and the quadrivium, the lower and upper divisions of the medieval liberal arts curriculum. The preponderance of biblical commentaries, theology and legal texts likewise reflects the character of advanced university study. This is the rump of a University Library equipped to satisfy the needs of medieval scholars and shows its state following the depredations occasioned by the Reformation: the neglect of books considered irrelevant to the new curriculum or which had been superseded by printed editions, the removal and misappropriation of volumes while the institutional grip on the collection was loosened, or (perhaps) the deliberate sequestering of library books elsewhere during the years of greatest upheaval.

The list compiled in 1574 by John Caius, though usually overlooked, is valuable for what it tells us not only about the losses the Library sustained over these years but also for providing, at a glance, an overview of the kinds of books the Library contained. Unlike the other lists, it gives the books not by desk or stall, but by subject. We first encounter Grammar, Dialectic and Philosophy, Rhetoric and History, Arithmetic and Geometry and Astronomy, Cosmography and Music: groupings that correspond almost precisely to the trivium and the quadrivium, the lower and upper divisions of the medieval liberal arts curriculum. The preponderance of biblical commentaries, theology and legal texts likewise reflects the character of advanced university study. This is the rump of a University Library equipped to satisfy the needs of medieval scholars and shows its state following the depredations occasioned by the Reformation: the neglect of books considered irrelevant to the new curriculum or which had been superseded by printed editions, the removal and misappropriation of volumes while the institutional grip on the collection was loosened, or (perhaps) the deliberate sequestering of library books elsewhere during the years of greatest upheaval.

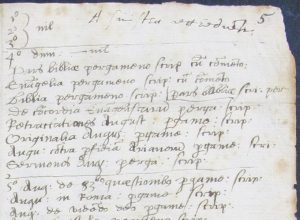

Shortly thereafter, a major reorganisation of the University Library occurred at the behest of Andrew Perne (?1519-1589), master of Peterhouse 1554-89, who was serving his third term (out of five) as Vice-Chancellor. Writing to the University Registrary, Matthew Stokys, Perne instructed him to measure the length, breadth, height and number of all of the bookshelves, and to move some of the remaining books in order to make space in anticipation of the arrival of new volumes Perne hoped to secure. A payment of two shillings in the Proctors’ Accounts followed, made to a ‘Hilary’, ‘for dressing the librarye and removing the old bookes’.

The catalogue of 1574 shows the library in this state of readiness. The first three stalls on the left, looking down the room towards the door at the southern end, are now completely empty; the fourth stall on the right was also vacated; two others, one on each side are also half-empty. Into these spaces went the benefactions that Perne succeeded in securing from a veritable Who’s Who of ecclesiastical dignitaries: Matthew Parker (1504-1575), archbishop of Canterbury; Robert Horne (1513×1515-1579), bishop of Winchester; and James Pilkington (1520-1576), bishop of Durham. Others also came from Sir Nicholas Bacon (1510-1579), Lord Keeper of the Great Seal.

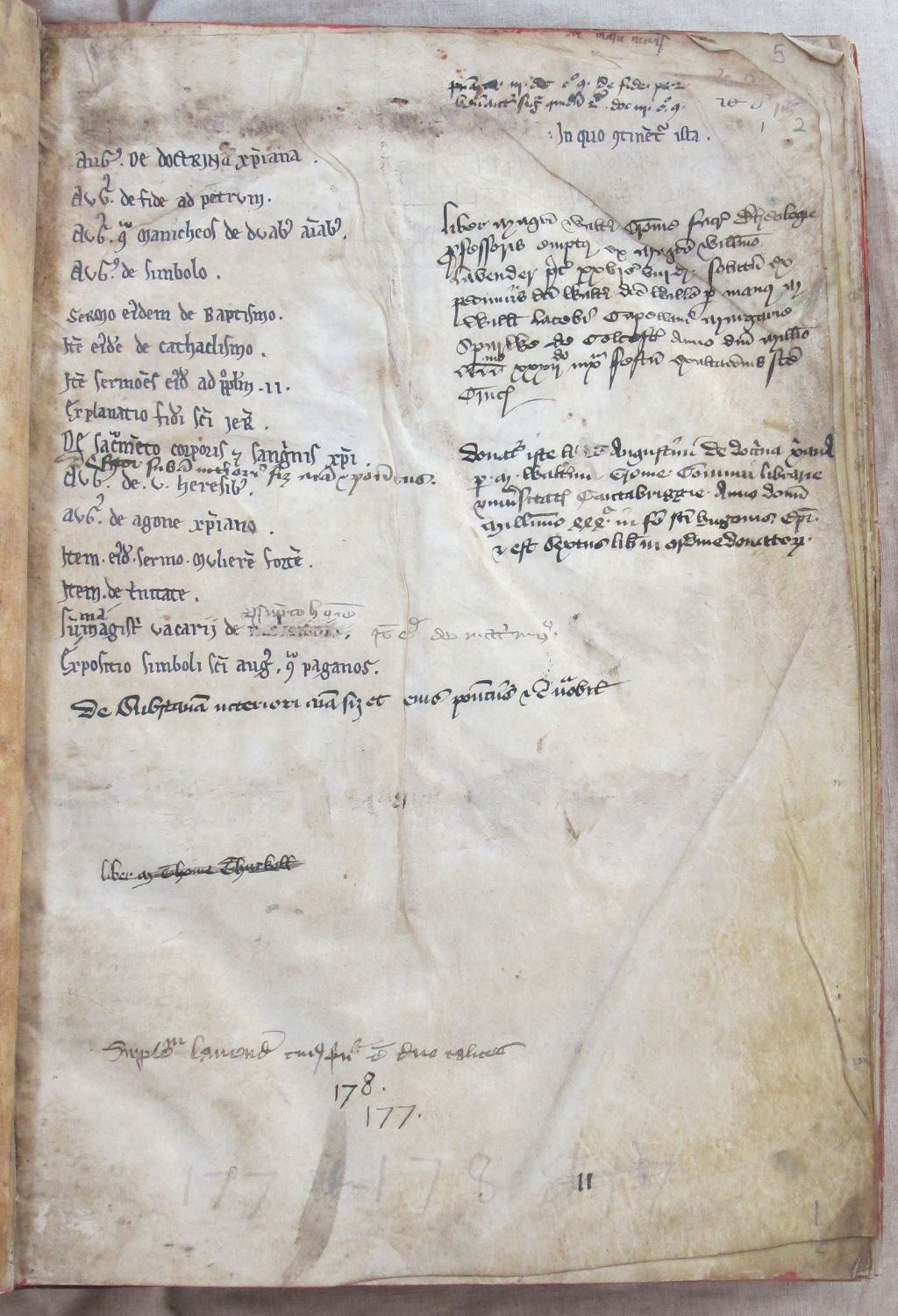

Contents list and inscription recording the gift of the book to the University Library by Walter Crome in 1433 – Ii.3.9, f. 2r

Comparison across the Library lists hints at another intriguing side to Perne’s campaign for its restoration and rejuvenation. Nine manuscripts present in the Ecloga Oxonio-Cantabrigiensis of 1600 are absent from each of the sixteenth-century catalogues – 1583, 1574 and 1556-57 – but present in the one from 1473. Seven of these were donated by Walter Crome, one of the medieval Library’s most important benefactors: his will of 1452 confirmed the gift of ninety-three volumes that had been promised to the Library. Oates is characteristically circumspect in stating that how they came into Perne’s possession ‘can only be guessed’ – but that it was not impossible that he removed them himself, perhaps in 1546-47, during his tenure as Proctor and when the Common Library was abandoned, or recognised them as former treasures elsewhere after their dispersal.

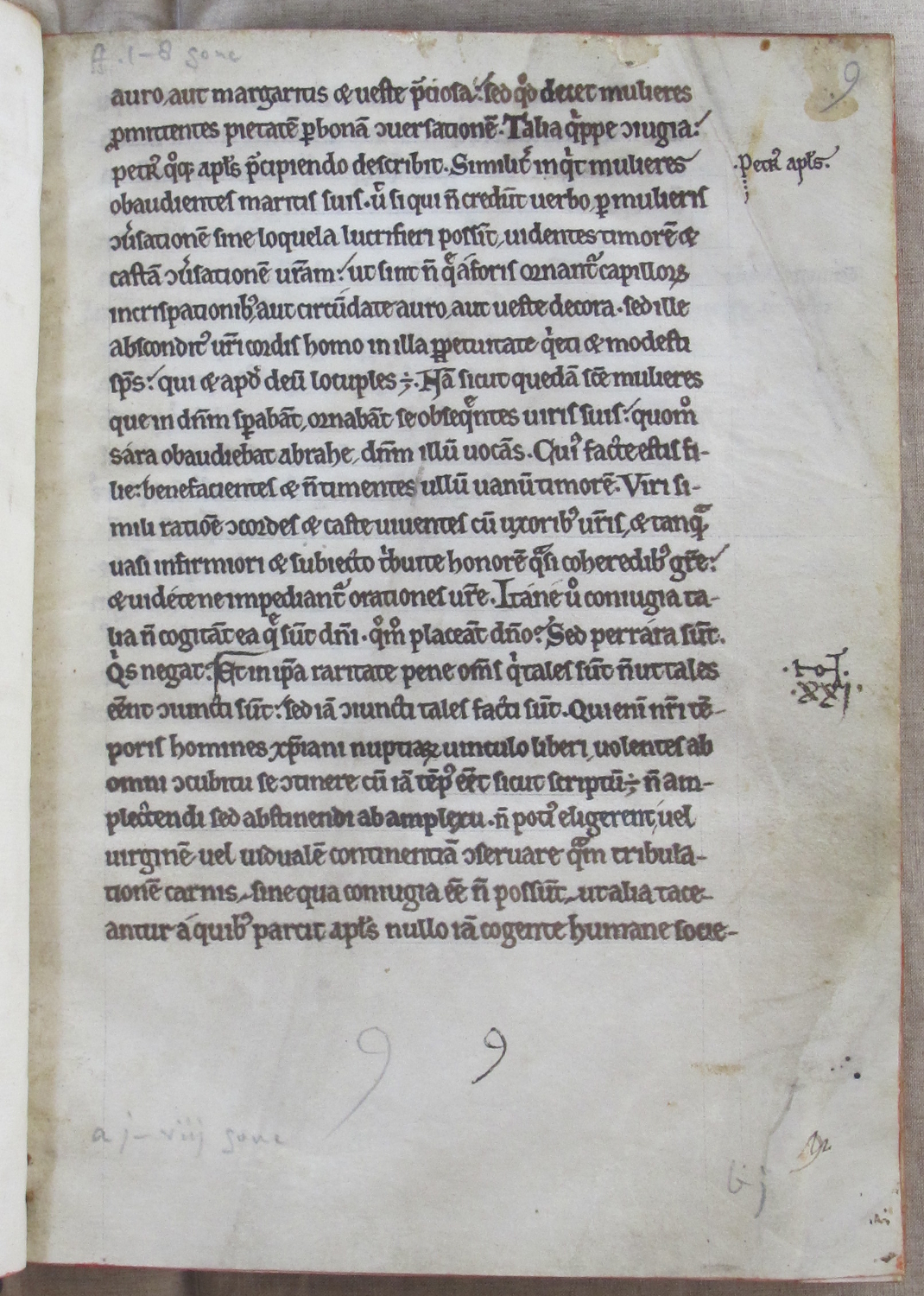

In any case, there are numerous other manuscripts that appear in the records, only to disappear and then appear once more: for instance, Ii.1.35, a copy of Augustine, De bono coniugali, or Dd.13.2, a compilation of works by Cicero. Both were first recorded in the 1556-57 catalogue; the latter is absent from those of 1573 and 1574, while the former is next recorded in 1600. The full story of many such manuscripts awaits elucidation.

The story of the University Library’s early collections is not one of continual growth and improvement. While one might mourn the loss of so many treasures, the records the reveal the Library’s changing fortunes are a source of continued bibliographical fascination. The upheavals precipitated by the break from Rome and the changes religious controversy wrought upon the University brought its Library close to utter ruin. Many of the choicest treasures among the medieval manuscripts – notably the corpus of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts from Matthew Parker – are here only as a consequence of Andrew Perne’s ministrations.

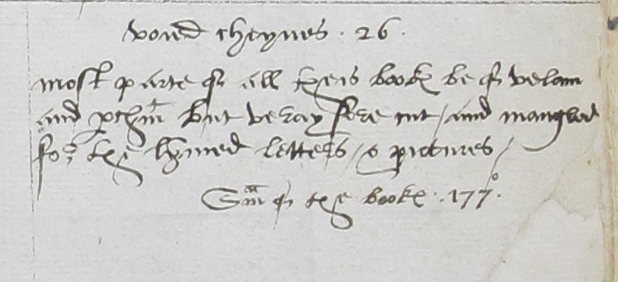

Note by Matthew Stokys in 1573, recording 26 chains from which books had been removed, and that, of those remaining, ‘Most parte of all theis bookes be of velam and parchment but be veray sore cut and mangled for the lymmed letters and pictures’ – UA, Grace Book Delta, f. 331r (inset)

For someone who held no official Library position, and who is quite invisible to Library readers, Perne played a decisive role in securing a stable future for the institution and its collections. By 1600, as Thomas James’s catalogue shows, the foundations of the modern University Library’s medieval manuscripts collection had been lain, providing a solid basis for the next three hundred years of expansion and scholarship.

This is the third in a series of blog posts about the early catalogues of the University Library. The other two are available at the following links.

1. ‘The Early Catalogues of the University Library: A New Subject Guide’

2. ‘Comings and Goings: The Movement of Manuscripts at the University Library before 1600’

Pingback: Comings and Goings: The Movement of Manuscripts at the University Library before 1600 – Cambridge University Library Special Collections