War and words: Colin Macaulay and his manuscript connections

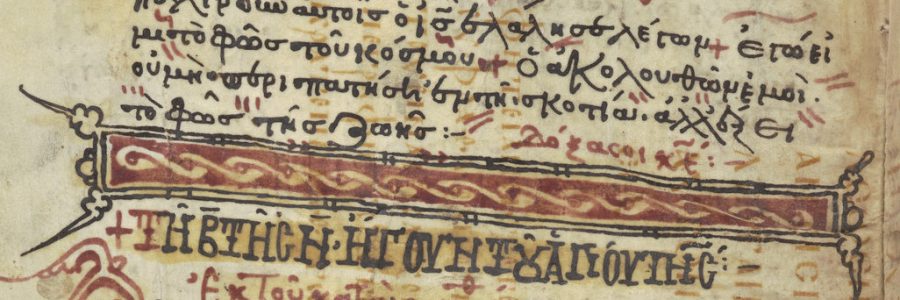

One of Cambridge University Library’s most treasured manuscripts, the Codex Zacynthius, is displayed in the Library’s exhibition ‘Ghost Words: reading the past’. The focus here is on palimpsest manuscripts, those in which text has been erased, and later the parchment reused for new text. In the Codex Zacynthius (MS Add.10062), the text visible to the naked eye is a lectionary with passages from the Gospels, probably copied in Rhodes in the 12th century CE, but underneath this is a text of St Luke’s Gospel with a commentary, written in Greek, from an earlier date of around 700 CE.

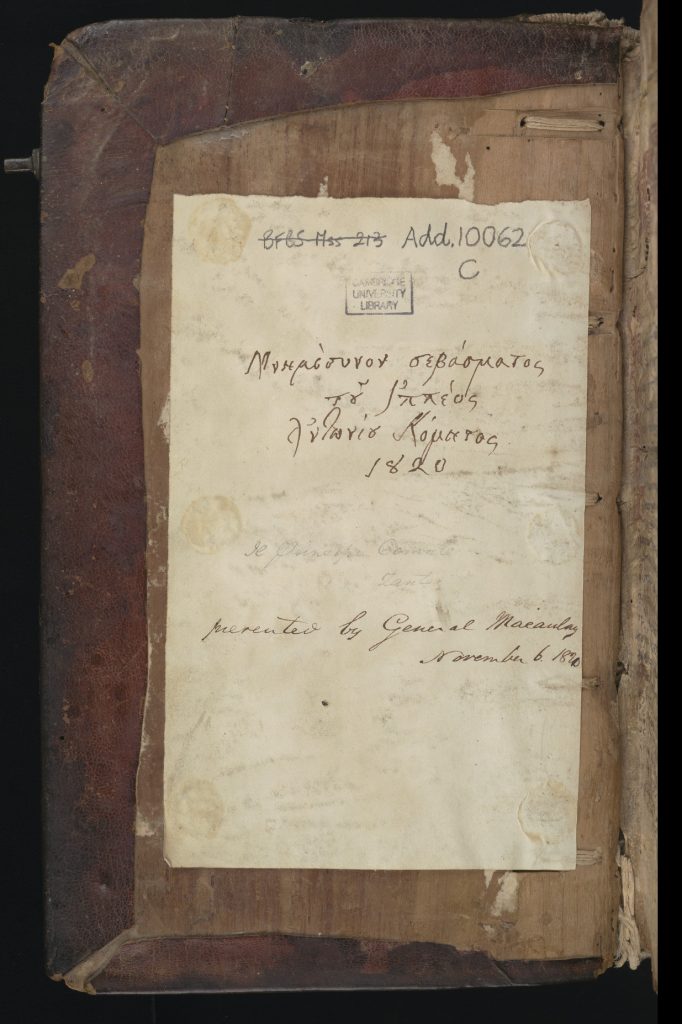

The manuscript was purchased by the Library in 2014 from the British and Foreign Bible Society, having been donated to them in 1821 by General Colin Macaulay (1760-1836). A man of many talents, Macaulay played a crucial role in the acquisition not only of this manuscript, but of others held in the Library.

Lieutenant Colin Macaulay, 1792, by John Smart, by permission of the Provost & Fellows of Kings

College, Cambridge

Colin Macaulay was born on the Island of Lismore in Argyll, the son of a Church of Scotland minister. As his is family of birth was large, an expensive education, including University, was out of the question. Aged seventeen, he decided to join the army; as a result, a large part of his adult life was spent abroad on campaign. Early in life he had developed personal traits and skills: a dedication to duty, to good works and philanthropy based on his Christian faith, and an intertest in languages and religious texts. He was said to have had a flair for learning languages, both classical and modern. All of this was to play a role in his later career.

In 1778, Macaulay joined the army of the East India Company, sailed to Calcutta and was immediately posted to Madras. The EIC forces had become embroiled in a series of wars against the rulers of Mysore, Hyder Ali and later, his son, Tipu Sultan, who had a deep hatred of the British presence in India. They were secretly allied with the French forces who had their own political aims in the region. Macaulay fought in the second Mysore War (1780-84), was taken prisoner and held captive in the capital, Seringapatam. He was imprisoned for more than three years in primitive, and some say barbaric, conditions, until his release in 1784.

In 1799, Macaulay also played a crucial role in the Battle of Seringapatam, which resulted in the death of Tipu Sultan and ended the Fourth Mysore War. He was also awarded the Seringapatam Gold Medal for his service. Macaulay served with Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington) who remained a friend for the rest of his life. It was subsequent to these hostilities, that Tipu Sultan’s fine library was appropriated by the East India Company, many of the volumes subsequently forming the basis of the India House Library in London. Three of these were sent to Cambridge: a fine copy of the Qur’an (MS Nn.3.75), one of Sa’di’s ‘Kullīyāt’ (MS Add.270) and one of Firdausi’s ‘Shahnama’ (MS Add.269). These are among the Library’s finest illuminated manuscripts from the Mughal Era.

In 1800, after his time in Mysore, the EIC appointed Macaulay to the post of Resident in Travancore and Cochin. He acted as the Governor-General’s ambassador and advisor and ensured taxes due to the Company were paid. Here he became a successful administrator at a time of great political unrest but at one point was the victim of an assassination attempt when his house in Cochin was attacked. He survived this by retreating for safely to a frigate anchored in the harbour.

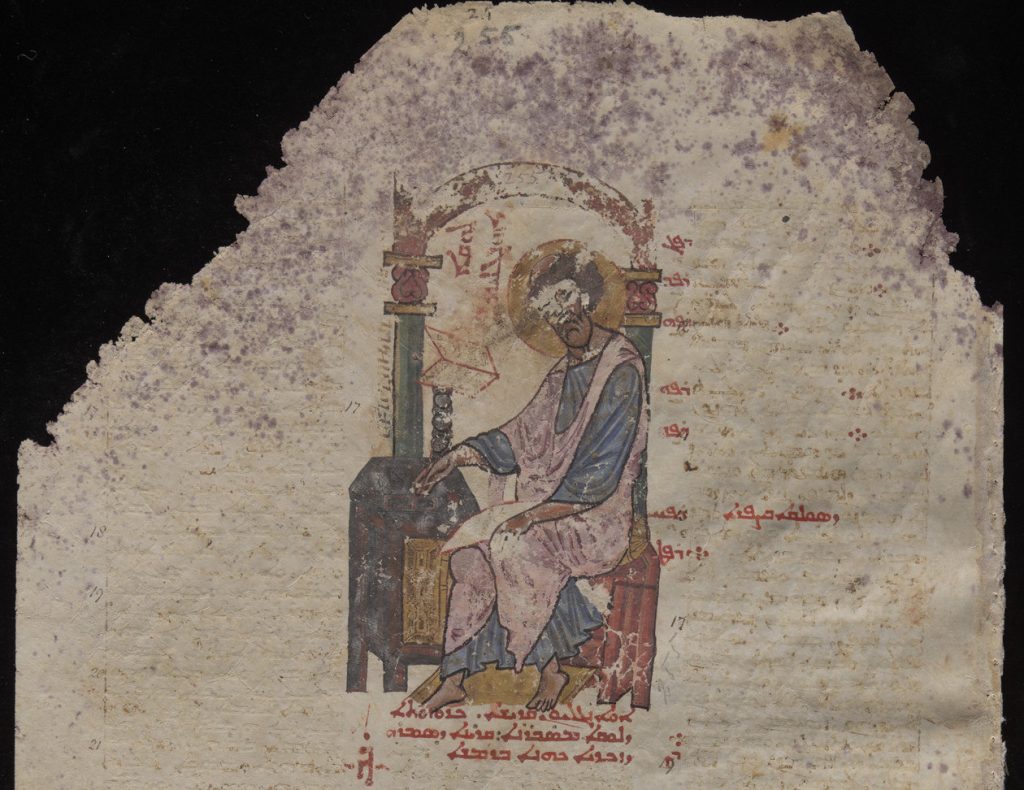

In Travancore, Macaulay developed a great interest in the thriving local community of Syriac Christians who were said to be descendants of an ancient community of St Thomas Christians dating from the sixth century. The Jewish community inhabiting the region was said to originate from an even earlier date. Here Macaulay met another Scot, the Reverend Claudius Buchanan (1766-1815), Vice-Principal of the College of Calcutta and previously a student at Queens’ College in Cambridge. Macaulay and Buchanan shared common interests in languages and ancient texts. Together they visited local Syriac churches and supported a project to translate the Bible into Malayalam, something initiated by local Christian monks in 1806 and which Macaulay later helped to supervise. Buchanan collected manuscripts in Syriac from the local churches and others in Hebrew from the synagogues in Cochin which he donated to the Library in 1809. In 1806, Mar Thoma VI the Metropolitan of the church of the Syrian Christians in Kerala had presented to Buchanan for safekeeping the treasured Buchanan Bible (Ms Oo.1.1-2). This unique Syriac text originating from 12th century Syria is understood to have been previously donated to the Indian Church by the Patriarch of Antioch. It came to the Library in 1809 along with the other Buchanan manuscripts.

It was during this time of shared interests with Buchanan that Macaulay rediscovered the Christian Malabar tablets (also known as the Quilon plates), inscribed rectangular copper plates which record the privileges and ancient rights granted to the Syriac Christian population in the region. Dating from the 9th century, these had been lost in the political turmoil but were fortunately rescued by Macaulay and returned to the Syriac Church authorities. Replicas of these were made, one of which came to Cambridge with the Buchanan manuscripts, eleven plates in all with inscriptions in Tamil, Malayalam, Arabic and Hebrew (Ms Oo.1.14).

In 1810, Macaulay returned to England, retaining his army post but no longer in active service. In 1830, he was promoted to Lieutenant-General in recognition of his achievements. He turned his attention to the Abolition of Slavery movement in which his brother Zachary, and his brother-in-law Thomas Babington were already deeply involved. Macaulay worked closely with them and with William Wilberforce, also with many other influential individuals such as Annabella, Lady Byron, (wife of the poet) and the Duke of Wellington. Macaulay attended the Congress of Verona in 1822, at which Wellington represented British interests and at which anti-slavery issues were discussed. Macaulay was valued here for his translating skills. Led by his interest in Bible translation, Macaulay became associated with the British and Foreign Bible Society, which had been founded by Wilberforce in London in 1804. He knew also of its library with many Bible texts, translations and theological works.

In later life Macaulay suffered ill-health, resulting perhaps from his long years in India and his incarceration in Seringapatam, so in the winter months he travelled to warmer climes in the Mediterranean. He frequently travelled on behalf of the Bible Society and in their archive are letters from Macaulay to the Society’s London offices concerning shipments of copies of the Bible, problems with type fonts and the constant search for more translators.

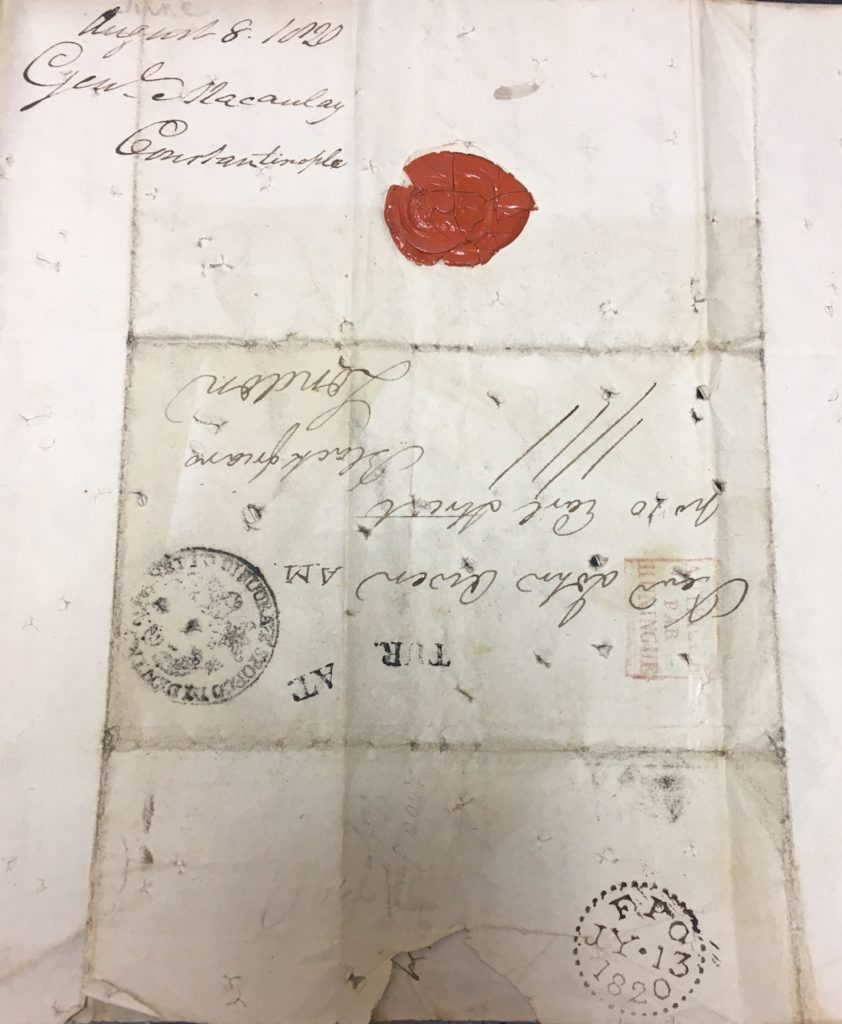

In 1820, Macaulay visited the island of Zacynthos (Zante) on behalf of the Society where he met Prince Antonio Comuto (1748-1833), President of the league of Ionian Islands known as Septinsular Republic. The Prince possessed a famous library which included the Codex Zacythius which the Prince presented to Macaulay as a token of his esteem. One letter from the Bible Society archive, dated June 1820 from Constantinople, could well have been written just prior to his visit to Zacynthos to acquire the manuscript. (MS BSA/D1/2). Macaulay returned with it to London and, the following year, donated it to the Bible Society. Inside the front binding of the manuscript there is a note dated 1820 by Prince Comuto, and below that, another by Macaulay recording his donation in November 1821.

More recently in 1985, the Bible Society decided to move to new premises in Swindon but there was insufficient room there for its Library so this was transferred on permanent loan to Cambridge University Library where it has been housed ever since with its own reading room and staff. In 2014, the Society decided to offer the Codex Zacynthius for sale to fund a new heritage centre building venture in Bala, Wales, and with the help of generous donations it was bought by Cambridge University Library.

An early attempt to read the undertext of the Gospel using only sunlight and a magnifying glass was made by the English biblical scholar Samuel Tregelles in 1861, and other attempts at decipherment followed. Only recently, in 2018-20, a project was carried out which enabled the lower text to be fully deciphered. This was carried out jointly by Cambridge and led by the Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing at Birmingham University. The imaging was carried out by the Early Manuscript Electronic Library (EMEL), based in the US, when each folio was photographed using multi-spectral imaging.

It is unclear how far Colin Macaulay understood the significance of the manuscript he carried with him from Greece, or how much he himself managed to decipher with the naked eye, but it would have been impossible at the time to envisage the new methodology which has since brought the text to light.

What is undeniable, though, is that without Macaulay’s voyage bringing the manuscript from Zacynthos to London in 1821, none of this would have been possible. Macaulay’s contribution is key to the manuscript’s presence in the exhibition where it can be appreciated by everyone.

References

Colin F. Smith, A Life of General Colin Macaulay; soldier, scholar & slavery abolitionist (Birmingham: Jones & Palmer, 2019)

Andrew Dalby, ‘A dictionary of oriental collections in Cambridge University Library’.

Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 9, 3 (1988): 248-80

David McKitterick, Cambridge University Library: a history. Vol. 2, The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.(Cambridge: CUP, 1986), 377-84.

C. A. Swanston, ‘Memoir of the primitive Church of Malayala’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1, 2 (1834): 171-92